Practice Essentials

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) is a clinical syndrome of clubbing of the fingers and toes, enlargement of the extremities, and painful, swollen joints. This condition is characterized by symmetric periostitis involving the radius and fibula and, to a lesser extent, the femur, humerus, metacarpals, and metatarsals. Most imaging studies and histologic examinations of clubbed fingers reveal hypervascularization of the distal digits. Cutaneous symptoms include thickening of the skin (pachyderma) and ptosis of the lids. [1] Cutaneous gland dysfunction can also occur, resulting in acne, hyperhydrosis, or seborrhea. [2, 3, 4, 5]

HOA can be primary or secondary. Approximately 3-5% of patients with HOA have primary HOA, or pachydermoperiostosis (PDP). [6, 7] The remaining 95-97% have secondary HOA, or hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA). [8, 9] The term HPOA emphasizes the pulmonary problems that represent a major cause of periostitis, although conditions other than pulmonary disorders may cause HPOA. HPOA is a syndrome in which clubbing of fingers and toes, arthritis, and periostitis occur. [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

(See the images below.)

Radiograph of both hands in a 42-year-old man with a family history of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy who had coarsened facial features and thickness of the scalp. Note the soft-tissue clubbing and acro-osteolysis of the terminal phalanges.

Radiograph of both hands in a 42-year-old man with a family history of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy who had coarsened facial features and thickness of the scalp. Note the soft-tissue clubbing and acro-osteolysis of the terminal phalanges.

Macroradiograph of the left hand in a patient known to have long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the shafts of the distal radius, ulna, metacarpals, and proximal phalanges (also see the next image).

Macroradiograph of the left hand in a patient known to have long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the shafts of the distal radius, ulna, metacarpals, and proximal phalanges (also see the next image).

Radiograph in a patient with long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal reaction around the lower parts of the femora.

Radiograph in a patient with long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal reaction around the lower parts of the femora.

Imaging modalities

Plain radiography is the mainstay of radiology-aided diagnosis, although the exact sensitivity of plain radiography is unknown. A chest radiograph can identify intrathoracic abnormalities when isolated clubbing is present. If clubbing is unilateral, it is often vascular or neurologic. Plain films of extremities may show tissue and bony abnormalities even in asymptomatic patients. New bone formation tends to be most evident in the subperiosteal region of the distal diaphysis of bones of the forearms and legs. Periostitis causes increased circumference of bone without changing its shape. Multiple layers of new bone are deposited, resulting in onion skin–like lesions in affected bones. There have also been reports of ossification of ligaments and interosseous membrane. [4]

In the case of long-standing clubbing, bone remodeling can cause osseous resorption at the terminal phalanges of the fingers and toes, which is termed acro-osteolysis. This finding is generally associated with primary HOA and congenital cyanotic heart disease. Tuftal overgrowth has also been identified in the phalanges. These 2 changes are usually in the toes first and then the fingers. [5, 9]

Nuclear medicine studies reveal early evidence of disease; its sensitivity is greater than that of other modalities.Radionuclide bone scanning may be useful for early diagnosis by demonstrating periosteal involvement. However, although sensitive, bone scan findings are nonspecific and may present in other conditions that display periosteal proliferation. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with CT may show evidence of periostitis and uptake of excess tracer in internal organs in secondary HOA. [4]

Radionuclide bone scanning with technetium-99m (99mTc)–methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is usually more sensitive for HOA than radiography alone. HOA is often diagnosed incidentally on bone scintigraphy in patients with malignancy. Symmetrical increased tracer uptake is typically seen at the periosteum linearly along the cortical margins of the diaphysis and metaphysis of the long tubular bones. This is known as the tram line or the double-stripe sign. Radionuclide scans can also help evaluate the therapeutic response. [9]

On MRI, periosteal reaction typically displays low-to-intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. MRI can also help identify synovial effusions. [9]

CT scanning is useful in elucidating the cause of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA), such as intrathoracic pathology or infected vascular grafts. [13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20]

Neither radiographic results nor radionuclide findings are specific for hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HPOA), and the differential diagnosis includes many entities (see below). However, a specific diagnosis can usually be achieved with clinical input.

Differential diagnosis and other problems to be considered

The differential diagnosis includes Caffey disease, fibrous dysplasia, and Paget Disease. Acromegaly may be suggested in cases of exuberant skin hypertrophy and enlarged hands and feet. Normal growth hormone levels and the absence of both prognathism and enlarged sella turcica exclude acromegaly. [21, 22]

When considering a diagnosis of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (primary HOA, pachydermoperiostosis. PDP), also take into account congenital syphilis, diaphyseal dysplasia (Camurati-Engelmann disease), infantile cortical hyperostosis, Caffey disease, and hypervitaminosis A.

When considering a diagnosis of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA), also consider acromegaly, thyroid acropachy, venous stasis, endosteal hyperostosis (van Buchem disease), macrodystrophia lipomatosa, Proteus syndrome, Paget disease, and fibrous dysplasia.

Radiography

Primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

The predominant radiographic feature of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA, pachydermoperiostosis) is periostitis, which is depicted as symmetric osseous thickening. Periostitis mostly affects the tubular bones of the limbs, especially the radius, ulna, tibia, and fibula, although the pelvis, carpus, tarsus, metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges may be involved (see the images below).

Periosteal proliferation is usually shaggy and is associated with irregular excrescences and diaphyseal expansion. Periosteal proliferation begins in the epiphyseal region at the tendon-muscle attachment. Rarely, thickening of the calvarium and skull base is seen.

The periostosis appears to progress in stages with respect to number of affected bones, site of involvement within bone, and shape of tuftal overgrowth periosteal reaction. Symmetrical periostosis in the extremities should cause secondary HOA to be considered, and a chest radiograph should be recommended for a suspected thoracic abnormality, particularly bronchogenic carcinoma. [5, 9]

In the case of long-standing clubbing, bone remodeling can cause osseous resorption at the terminal phalanges of the fingers and toes, which is termed acro-osteolysis. This finding is generally associated with primary HOA and congenital cyanotic heart disease. Tuftal overgrowth has also been identified in the phalanges. These 2 changes are usually in the toes first and then the fingers. [5, 9]

Radiograph of both hands in a 42-year-old man with a family history of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy who had coarsened facial features and thickness of the scalp. Note the soft-tissue clubbing and acro-osteolysis of the terminal phalanges.

Radiograph of both hands in a 42-year-old man with a family history of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy who had coarsened facial features and thickness of the scalp. Note the soft-tissue clubbing and acro-osteolysis of the terminal phalanges.

Macroradiograph of the left hand in a patient known to have long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the shafts of the distal radius, ulna, metacarpals, and proximal phalanges (also see the next image).

Macroradiograph of the left hand in a patient known to have long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the shafts of the distal radius, ulna, metacarpals, and proximal phalanges (also see the next image).

Radiograph in a patient with long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal reaction around the lower parts of the femora.

Radiograph in a patient with long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal reaction around the lower parts of the femora.

A 53-year-old male smoker presented with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles. A chest radiograph was obtained as a part of the workup and demonstrated an opacity in the left apical region (arrow) suggestive of a bronchial neoplasm. Results of percutaneous needle biopsy confirmed a squamous carcinoma (see also the next image).

A 53-year-old male smoker presented with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles. A chest radiograph was obtained as a part of the workup and demonstrated an opacity in the left apical region (arrow) suggestive of a bronchial neoplasm. Results of percutaneous needle biopsy confirmed a squamous carcinoma (see also the next image).

Radiograph in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows a subtle periosteal reaction around the upper parts of the femora on the medial aspects (see also the next image).

Radiograph in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows a subtle periosteal reaction around the upper parts of the femora on the medial aspects (see also the next image).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the right ankle in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the lower shafts of the tibia and fibula.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the right ankle in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the lower shafts of the tibia and fibula.

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) usually involves diaphyseal and metaphyseal periostitis. Periosteal proliferation is usually single or laminated and is either regular or irregular. Laminated periostitis may have an onionskin appearance. Symmetrical periostosis in the extremities should cause secondary HOA to be considered, and a chest radiograph should be recommended for a suspected thoracic abnormality, particularly bronchogenic carcinoma. [5, 9, 8]

Initially, periostitis is symmetrical and involves the tibia, fibula, radius, ulna, and, less commonly, the femur, humerus, metacarpals, metatarsal, and phalanges on both sides. Eventually, periosteal proliferation extends into the metaphysis. Periosteal proliferation rarely extends into the epiphysis, except in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease, in whom the epiphysis may be affected. In rare cases, periostitis affects the ribs, clavicles, and scapula.

Periarticular soft-tissue swelling, clubbing, and clinical and radiologic features of an underlying primary lesion are often depicted. Digital clubbing associated with soft-tissue swelling may be depicted on plain radiographs. Occasionally, focal areas of tuft hypertrophy or bone resorption may be seen.

Clinically, joint involvement (eg, in the wrists, knees, ankles, and small joints of the hands) in patients with HPOA may mimic inflammatory arthritis. The presence of soft-tissue swelling, joint effusion, and juxta-articular osteoporosis accentuate the clinical difficulty in making a diagnosis. However, synovial inflammation associated with HPOA is usually mild, and erosive change and loss of joint cartilage space are not features of HPOA.

Chest radiographs may reveal the underlying cause of HPOA.

False positives/negatives

Although similar osseous changes may occur in both primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA, pachydermoperiostosis) and hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA), periostitis in HOA more commonly extends into the epiphysis. Poorly defined bony outgrowths are more characteristic of HOA. These outgrowths may also affect the axial skeleton. In patients with HOA, these changes occur at an earlier age because of the familial nature of the disease. Differences in the pattern of bone involvement in HOA and HPOA are partly related to the earlier age of onset in patients with HOA and the resulting longer duration of the bony changes.

In patients with HPOA, changes develop at a later age, except in patients with conditions such as cyanotic heart disease; in these patients, the changes more closely resemble those of HOA. The irregular periosteal proliferation in the metaphysis and epiphysis among patients with HOA is not usually seen in patients with HPOA. The patient's family history, the early appearance of osseous changes, and the absence of joint pain help in differentiating HOA from HPOA.

Patients with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) occasionally have diaphyseal periostitis, particularly in the femur and humerus. Occasionally, the metacarpals are involved; this finding mimics that of HOA.

Thyroid acropachy is an unusual complication of thyrotoxicosis, which is associated with periostitis; it can mimic HOA on radiographs. However, the clinical features are distinct; exophthalmos, soft-tissue swelling, pretibial myxedema, and clubbing are present. The condition is usually observed in patients with thyrotoxicosis after having undergone treatment; patients may be euthyroid or hypothyroid. Periostitis in thyroid acropachy appears fluffy and spiculated. It mostly affects the periosteal bone in the hands and feet and is rarely seen elsewhere.

Hypervitaminosis A may cause periosteal proliferation, but the clinical and radiographic features enable one to distinguish this disease from HOA. Periostitis is usually diaphyseal, with undulating contour; it is often associated with epiphyseal abnormalities, soft-tissue nodules, and intracranial hypertension.

Endosteal hyperostosis (van Buchem disease) is characterized by thickening of the skull vault and tubular bones, but clubbing is not observed. Skin changes, thickening of the paranasal sinuses, and extension of periosteal proliferation into the epiphysis are features of HOA and do not occur in endosteal hyperostosis.

Acromegaly and HOA share some clinical and radiographic features, but the 2 conditions are seldom confused.

In patients with chronic venous stasis, periosteal proliferation is confined to the lower limbs. The condition is characterized by undulating periosteal contour and cortical thickening; it is associated with soft tissue swelling, ulceration, and calcified phleboliths.

Infantile cortical hyperostosis (Caffey disease) typically affects the young; it is usually associated with extreme proliferative periostitis of the mandible, clavicle, scapula, ribs, and tubular bones. Cranial destruction, bone deformities, and soft-tissue nodules may occur in infantile cortical hyperostosis. The clinicoradiologic features of infantile cortical hyperostosis are distinct, and it is usually not confused with HPOA or HOA.

The radiographic features of Paget disease, fluorosis, fibrous dysplasia, macrodystrophia lipomatosa, and Proteus syndrome are sufficiently distinct not to cause confusion with HPOA or HOA.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI findings in patients with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) were described in a solitary case in which 2 main features were observed: soft-tissue changes and periostitis. The soft-tissue component appeared as an area of high signal intensity on T2-weighted and short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) images. The findings consisted of muscular and septal edema associated with extensive soft-tissue swelling that surrounded the femur and the attached cortex but not the bone. These features were believed to be consistent with an inflammatory process, which was probably highly vascularized, similar to reactive edema or fibrovascular proliferation. MRI depiction of periostitis is not usually reliable, but in the reported case, periostitis was easily identified through use of a surface coil; periostitis appeared as a wavy, thin, hypointense line surrounding the cortex. [19, 20]

Experience is insufficient for assessing the reliability of MRI in the diagnosis of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA). Apparently, the reported case indicated that the soft-tissue component of the disease is depicted better on MRIs than on other images.

The improved sensitivity of MRI in the detection of soft-tissue edema may suggest an erroneous diagnosis of hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) if MRI is the initial modality used, because many inflammatory, posttraumatic, and neoplastic conditions have features similar to those of HOA.

Nuclear Imaging

Nuclear medicine studies reveal early evidence of disease; its sensitivity is greater than that of other modalities. Radionuclide bone scanning may be useful for early diagnosis by demonstrating periosteal involvement. However, although sensitive, bone scan findings are nonspecific and may present in other conditions that display periosteal proliferation. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with CT may show evidence of periostitis and uptake of excess tracer in internal organs in secondary HOA. [4]

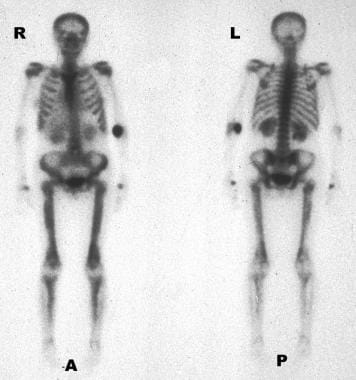

Isotope bone scanning with technetium-99m (99mTc)–labeled diphosphonate shows evidence of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) early in the course of disease (see the following image). Isotope uptake is symmetrically increased in the tubular bones along the cortical margins of the diaphysis and metaphysis. Uptake may be irregular, or it may create a double-stripe or parallel-track sign. Periarticular radionuclide uptake may be increased as a result of associated synovitis. Isotope bone scans show high rates of mandibular involvement (40% of patients) and scapular involvement (>60% of patients); these rates are considerably higher than the rates of such involvement as determined with the use of radiographs. Radionuclide uptake findings may be normal after a month of successful therapy. [23, 9]

Differential diagnosis. Radionuclide scans show the typical appearance of secondary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy caused by a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Differential diagnosis. Radionuclide scans show the typical appearance of secondary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy caused by a bronchogenic carcinoma.

Degree of confidence

Scintigraphic findings in patients with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA) appear earlier than radiographic findings do, and they correspond well to the clinical findings. Activity decreases with successful therapeutic measures, such as surgery or radiation therapy. Tumor recurrence may be associated with recurrent findings of increased radionuclide uptake.

Although isotope bone scanning is a highly sensitive means of assessing hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (HPOA), its findings are nonspecific, and similar findings can occur with other forms of periosteal proliferation.

-

Radiograph of both hands in a 42-year-old man with a family history of primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy who had coarsened facial features and thickness of the scalp. Note the soft-tissue clubbing and acro-osteolysis of the terminal phalanges.

-

Macroradiograph of the left hand in a patient known to have long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the shafts of the distal radius, ulna, metacarpals, and proximal phalanges (also see the next image).

-

Radiograph in a patient with long-standing bronchiectasis shows extensive lamellar periosteal reaction around the lower parts of the femora.

-

A 53-year-old male smoker presented with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles. A chest radiograph was obtained as a part of the workup and demonstrated an opacity in the left apical region (arrow) suggestive of a bronchial neoplasm. Results of percutaneous needle biopsy confirmed a squamous carcinoma (see also the next image).

-

Radiograph in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows a subtle periosteal reaction around the upper parts of the femora on the medial aspects (see also the next image).

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the right ankle in a 53-year-old male smoker with lower-limb pain around the hips, knees, and ankles shows lamellar periosteal new bone formation around the lower shafts of the tibia and fibula.

-

Radiograph in a 32-year-old woman treated for Graves disease (thyrotoxicosis) who presented with a vague discomfort in the hands. Radiograph shows a mixture of hair-on-end and lamellar periosteal reaction around the distal shafts of the second metacarpal bones caused by thyroid acropachy.

-

Differential diagnosis. Radiograph of the lower legs in a patient presenting with infected ulceration of the right lower leg caused by venous insufficiency. Note the extensive lamellar periosteal new bone around the shafts of the tibia and fibula.

-

Lateral radiograph of the tibia and fibula in a patient with chronic venous insufficiency shows periosteal new bone formation around the tibia and fibula. Note the arterial and venous calcifications.

-

Differential diagnosis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the femur in an athlete with a previous history of trauma to the thigh shows a traumatic periostitis of the mid femur. Note the calcific myositis.

-

Differential diagnosis. Radiograph of the arm in a 3-month-old male infant presenting with fever and irritability shows massive periosteal new bone formation around the humerus, radius, and ulna associated with infantile cortical hyperostosis (Caffey disease). Note the sparing of the proximal phalanges.

-

Differential diagnosis. Radionuclide scans show the typical appearance of secondary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy caused by a bronchogenic carcinoma.