Practice Essentials

Hydrops fetalis is a serious fetal condition defined as abnormal accumulation of fluid in 2 or more fetal compartments, including ascites, pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, and skin edema. In addition, hydrops fetalis is associated with polyhydramnios and a thickened placenta (>6 cm) in as many as 30-75% of patients. Many affected fetuses also have hepatosplenomegaly. [1, 2] The imbalance in fluid homeostasis, with more fluid accumulating than can be resorbed, can result from 2 broad categories of pathologies—namely, those of an immune origin and those of a nonimmune origin. [3, 4, 5, 6]

Immune-related hydrops fetalis (IHF) results from alloimmune hemolytic disease or Rh isoimmunization and before routine immunization of Rh-negative mothers, with most cases being caused by erythroblastosis from Rh alloimmunization. With the introduction of widespread immunoprophylaxis for red blood cell alloimmunization and the use of in utero transfusions for immune hydrops therapy, IHF represents a minority of cases. Although a dramatic reduction in RhD sensitization has been achieved with Rh immunoglobulin (RhIg), the disorder has stubbornly persisted in a small group of women, many of whom have become isoimmunized from repeated exposure to foreign RBC antigens on contaminated needles used for administering illicit drugs. The rise in illicit intravenous (IV) opioid use during pregnancy has been reported to lead to isoimmune hemolysis in the fetus, which results in fetal death or severe hydrops fetalis. [7]

Nonimmune-related hydrops fetalis (NIHF) now accounts for almost 90% of cases of hydrops. [8] Causes of NIHF include primary myocardial failure, high-output cardiac failure, decreased colloid oncotic plasma pressure, increased capillary permeability, and obstruction of venous or lymphatic flow. [9] Fetal cardiac anomalies are the most common cause of NIHF, and chromosomal anomalies are the second-most-common cause. [10]

Mirror syndrome is a rare entity characterized by maternal disease that mimics fetal hydrops. In mirror syndrome, maternal hypertension, edema, and often proteinuria are present in association with fetal hydrops. This entity was first described in association with rhesus (Rh) immunization, although it is most commonly associated with NIHF of an unknown etiology. Mirror syndrome is life threatening to both the mother and the fetus if not noticed and if left untreated. [11]

Mortality and mortality figures vary, but in general, mortality is 27-36%. [12] A report of data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development regarding 1037 live-born infants with NIHF revealed a 35.1% neonatal mortality and a 43.2% overall mortality at age 1 year. Poor prognostic factors were prematurity, polyhydramnios, and large for gestational age. [13] In a separate report that analyzed data from an international registry of 69 survivors with hemoglobin Bart hydrops fetalis, investigators found that more than half survived beyond age 5 years (N= 39; 56.5%), of whom about half (N=18; 26.1%) were older than 10 years. [14]

Hydrops fetalis is often diagnosed with routine sonograms in which the typical features are depicted. In other fetuses, a clinical suspicion of hydrops fetalis may exist because of a previous family history of a similarly affected baby or because ultrasonography is performed to evaluate polyhydramnios.

Preferred examination

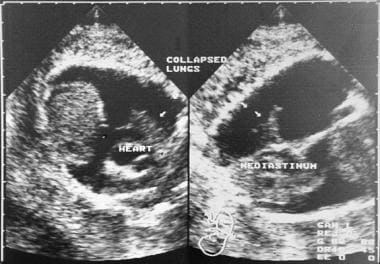

Ultrasonographic findings (see the images below) are often reliably helpful in the diagnosis of the disease causing fetal hydrops, especially in fetuses in whom a chest mass or cardiac disease is present. However, in many fetuses, an exact etiology is not forthcoming after an ultrasonographic examination.

Blood tests performed in the mother can provide information regarding Rh and other immune causes of hydrops fetalis, as well as evidence of infection and metabolic diseases. However, invasive fetal testing must eventually be performed by means of amniocentesis or cordocentesis. Both methods pose a risk of fetal death.

A history of a previously affected fetus in the family is of critical importance. Once IHF is suspected, maternal blood typing and antibody screening against Rh and a determination of minor blood types (eg, Kell, Duffy, MNSs) should be performed. In mothers in whom IgM is detected, no further workup is needed, but if IgG is detected, titers of Rh-positive antibodies in the maternal blood need to be determined. A titer that is greater than 1:16 is significant. If the titer results are significant, amniocentesis should be performed to assess the severity of fetal hemolysis and anemia.

Fetal anemia can be monitored either by direct sampling of the fetal blood via cordocentesis or by determining the delta optical density (OD) using a wavelength of 450 μm in the amniotic fluid. This measurement gives an estimate of bilirubin levels during the third trimester. Delta OD results are plotted on the Liley 3-zone chart. The closer the results are to the third zone, the greaternthe risk of IHF. A fetal hematocrit determination is the final test to be performed, and fetal transfusion should be considered in fetuses with a hematocrit level that is less than 40%.

NIHF can result from a large number of causes, including chromosomal abnormalities, cardiac failure, tumors, and twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Extensive clinical workup is required to attempt to identify the specific etiology. In patients in whom NIHF is suspected, the search for a cause starts with a maternal evaluation. Initial clinical history taking should be directed toward the presence of hereditary or metabolic diseases, diabetes, infections, anemias, and the use of all medications.

Initial investigations for NIHF include an indirect Coombs test to exclude immune causes, followed by the determination of routine blood counts and indices to exclude thalassemias; maternal blood chemistry testing for G6PD deficiency; Betke-Kleihauer testing for fetal-maternal transfusion; and screening for toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, CMV, and herpes simplex (TORCH) infection during intrauterine pregnancy.

Amniocentesis is needed to perform fetal karyotyping, amniotic fluid culturing, testing for CMV infections, assessment of α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, testing for thalassemia, and determination of the lecithin-sphingomyelin (L/S) ratio. Karyotyping can also be performed with tissue obtained by chorionic villous sampling (CVS) or with fluid obtained from one of the fetal cavities. A chromosome count and karyotype can be obtained rapidly by using the fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) technique. The FISH technique can also help detect specific deletions and chromosomal rearrangements, and the results are often available within 24-48 hours.

Fetal blood tests should include hemoglobin chain analysis for thalassemia and fetal serum albumin levels.

Initially, ultrasonographic findings suggest hydrops fetalis in most cases, and this modality can also be used for follow-up imaging to observe the progress of the condition if the pregnancy is continued.

Imaging features

The sonographic features of hydrops fetalis are defined as the presence of 2 or more abnormal fluid collections in the fetus. These include ascites, pleural effusions, pericardial effusion, and generalized skin edema (defined as skin thickness >5 mm). Other frequent findings include placental thickening (typically defined as a placental thickness ≥4 cm in the second trimester or ≥6 cm in the third trimester) and polyhydramnios. [8]

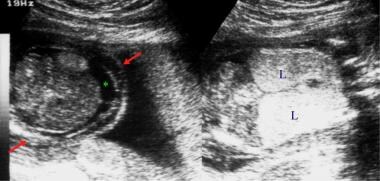

Ascites may be small and may be just enough to form a film over the abdominal contents, or ascites may be extensive, with the contents of the abdomen, liver, and gut floating in the fluid (see the images below). The ascites may extend into the scrotum to form a hydrocele.

Left: Transverse section of the fetal abdomen. Right: Coronal section of the fetal thorax. These sonograms show ascites (asterisk) and echogenic lungs (L). This fetus had tracheal atresia. The red arrows indicate skin edema.

Left: Transverse section of the fetal abdomen. Right: Coronal section of the fetal thorax. These sonograms show ascites (asterisk) and echogenic lungs (L). This fetus had tracheal atresia. The red arrows indicate skin edema.

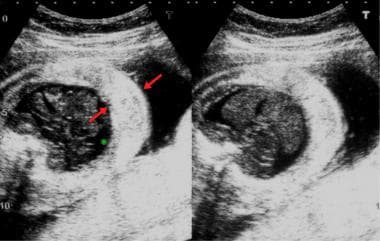

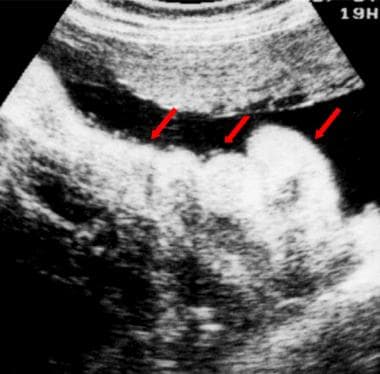

Transverse sections of the fetal abdomen. These sonograms show small ascites (asterisk) and gross skin edema (red arrows).

Transverse sections of the fetal abdomen. These sonograms show small ascites (asterisk) and gross skin edema (red arrows).

Plain radiograph of the chest and abdomen of a neonate. This image shows a markedly distended abdomen with centrally located bowel loops that are suggestive of ascites. The soft tissues are edematous although the lung fields are clear.

Plain radiograph of the chest and abdomen of a neonate. This image shows a markedly distended abdomen with centrally located bowel loops that are suggestive of ascites. The soft tissues are edematous although the lung fields are clear.

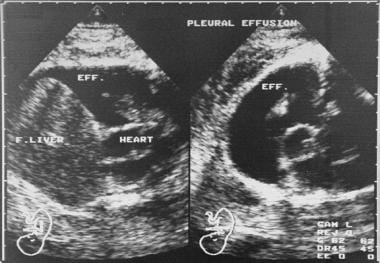

Pleural effusions can be unilateral or bilateral (see the images below). Unilateral effusions indicate the presence of a process such as chylothorax. Large effusions can compress the mediastinal vessels, cause upper body edema, and interfere with esophageal functioning to cause secondary polyhydramnios.

Coronal (left) and axial (right) fetal sonograms obtained late in the second trimester. These images show a large pleural effusion. The parents were from the Far East, and an earlier pregnancy had ended because of α thalassemia, which is a major cause of nonimmune-related hydrops fetalis in the Far East. The condition is uniformly fatal and associated with a significant risk of maternal morbidity. The α thalassemia gene is found in 20-30% of the population in Southeast Asia. The fetus was lost within 1 week of the ultrasonographic examination. Eff. = effusion; F. liver = fetal liver.

Coronal (left) and axial (right) fetal sonograms obtained late in the second trimester. These images show a large pleural effusion. The parents were from the Far East, and an earlier pregnancy had ended because of α thalassemia, which is a major cause of nonimmune-related hydrops fetalis in the Far East. The condition is uniformly fatal and associated with a significant risk of maternal morbidity. The α thalassemia gene is found in 20-30% of the population in Southeast Asia. The fetus was lost within 1 week of the ultrasonographic examination. Eff. = effusion; F. liver = fetal liver.

Edema may be localized to one part of the body, or it may be generalized. Edema is seen most easily over the skull, over which a halo is formed (see the images below). Edema may be seen in other parts of the body, as well.

Transverse sonogram of a normal fetal head. The hair is visible as an irregular halo and can cause confusion with scalp edema.

Transverse sonogram of a normal fetal head. The hair is visible as an irregular halo and can cause confusion with scalp edema.

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

The distribution and size of fluid accumulations may indicate the pathology. In IHF, ascites appears first, with edema and pleural collections appearing late. The findings of a specific organ pathology, such as skeletal abnormalities or cardiac tumors, may indicate a specific cause in hydrops fetalis.

Guidelines

The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) has released guidelines on the diagnosis and management of NIHF, recommending the following tests for initial evaluation [8] :

-

Antibody screen (indirect Coombs test) to verify that it is nonimmune.

-

Targeted sonography with echocardiography to evaluate for fetal and placental abnormalities.

-

Middle cerebral arterial (MCA) Doppler evaluation for anemia.

-

Fetal karyotype or chromosomal microarray analysis, regardless of whether structural fetal anomalies are identified.

The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada released updated guidelines for the investigation and management of non-immune fetal hydrops, including the following key recommendations [15] :

-

All patients with fetal hydrops should be referred to a tertiary care center for evaluation.

-

Fetal chromosome analysis through array comparative genomic hybridization (microarray) molecular testing should be offered where available in all cases of nonimmune fetal hydrops.

-

Imaging studies should include comprehensive obstetric ultrasound (including arterial and venous fetal Doppler) and fetal echocardiography.

-

Investigation for maternal-fetal infections and alpha-thalassemia should be performed in all cases of unexplained fetal hydrops in women at risk because of their ethnicity.

-

To evaluate the risk of fetal anemia, Doppler measurement of the middle cerebral artery peak systolic velocity should be performed in all hydrops fetuses after 16 weeks of gestation.

-

In case of suspected fetal anemia, fetal blood sampling and intrauterine transfusion should be offered rapidly.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Exquisite anatomic detail can be depicted on magnetic resonance images (MRIs), especially on those obtained with newer algorithms that allow fast acquisitions and that minimize the effect of fetal movement. However, MRI has not become a standard modality for imaging fetal hydrops because of the limited availability of state-of-the-art equipment for fast imaging and because of the expense involved. In addition, ultrasonography is widely available and can adequately provide most of the required information. These factors have hindered a wider use of MRI in fetal imaging.

Early detection of cerebral damage in a fetus associated with hydrops and cytomegalovirus infection is possible with fetal MRI. Salmaso et al described a case of a woman presenting at 21 weeks' pregnancy with active CMV infection. [16] Although a cerebral ultrasound examination had been normal, an MRI scan revealed a thickened germinal matrix, which was histologically confirmed and which was associated with underdevelopment of the gyri.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography remains the cornerstone of fetal imaging in fetuses in whom hydrops fetalis is suspected. Sonograms demonstrate the cardinal signs of the disease—namely, fetal skin edema (>5 mm) (see ithe mages below), fluid in a serous cavity, polyhydramnios, and a thickened placenta. These signs can be seen in different combinations and to differing extents in various diseases. [17] Additional findings, depending on the specific etiology causing the fetal hydrops, are occasionally seen as well. [18, 19]

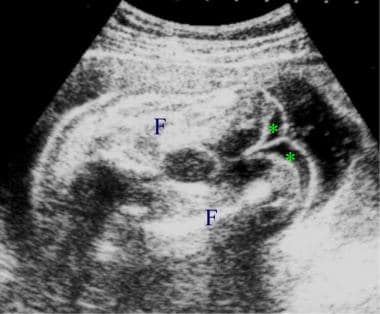

Sonogram depicting gross skin edema involving the legs. The asterisks indicate edema of the lower ends of the thighs. F = femur.

Sonogram depicting gross skin edema involving the legs. The asterisks indicate edema of the lower ends of the thighs. F = femur.

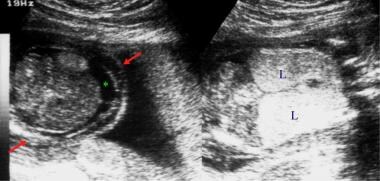

Left: Transverse section of the fetal abdomen. Right: Coronal section of the fetal thorax. These sonograms show ascites (asterisk) and echogenic lungs (L). This fetus had tracheal atresia. The red arrows indicate skin edema.

Left: Transverse section of the fetal abdomen. Right: Coronal section of the fetal thorax. These sonograms show ascites (asterisk) and echogenic lungs (L). This fetus had tracheal atresia. The red arrows indicate skin edema.

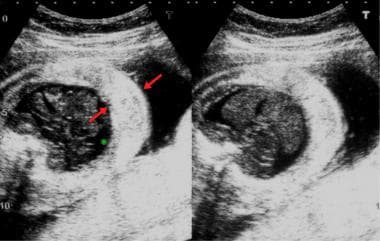

Transverse sections of the fetal abdomen. These sonograms show small ascites (asterisk) and gross skin edema (red arrows).

Transverse sections of the fetal abdomen. These sonograms show small ascites (asterisk) and gross skin edema (red arrows).

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

The minimum diagnostic criteria include the following: fluid accumulation in at least 2 serous cavities (ascites, pleural effusion, or pericardial effusion) or 1 serous effusion and generalized anasarca. A single site of fluid accumulation is generally not enough to diagnose hydrops fetalis unless a preexisting pathology that is strongly associated with this condition (eg, chest mass) is also present.

A few conditions mimic full-blown hydrops fetalis, but individual components of hydrops fetalis can be seen in other conditions, even as normal variants.

Normal fetal hair and a thick scalp can occasionally be seen, and this finding must be differentiated from skin edema (see the images below). Similarly, cystic hygromas and loops of cord near the body wall can suggest skin thickening. Occasionally, a thick layer of subcutaneous fat may cause confusion.

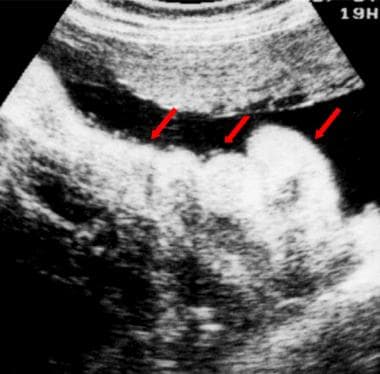

Sonogram depicting crocodile skin in a fetus. This condition is a normal finding in some fetuses; the folded, apparently thickened skin (red arrows) can be confused with skin edema.

Sonogram depicting crocodile skin in a fetus. This condition is a normal finding in some fetuses; the folded, apparently thickened skin (red arrows) can be confused with skin edema.

Transverse sonogram of a normal fetal head. The hair is visible as an irregular halo and can cause confusion with scalp edema.

Transverse sonogram of a normal fetal head. The hair is visible as an irregular halo and can cause confusion with scalp edema.

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.

Thick, folded skin, occasionally termed crocodile skin, is a normal variant that can cause confusion with skin edema (see the image below).

Sonogram depicting crocodile skin in a fetus. This condition is a normal finding in some fetuses; the folded, apparently thickened skin (red arrows) can be confused with skin edema.

Sonogram depicting crocodile skin in a fetus. This condition is a normal finding in some fetuses; the folded, apparently thickened skin (red arrows) can be confused with skin edema.

A congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung, a diaphragmatic hernia, and a bronchogenic cyst can suggest pleural effusions.

Pseudoascites, obstructed or mature bowel, fetal abdominal cysts, and an obstructed urinary system can mimic ascites. Pseudoascites refers to an artifactual hypoechoic rim that is sometimes seen in the fetal abdomen; this is due to hypoechoic, deep abdominal wall muscles or the diaphragm. Pseudoascites usually disappears when scanning is performed from another direction.

Other features that differentiate pseudoascites from ascites are as follows:

-

Pseudoascites is not seen past the anterior edge of the ribs.

-

Pseudoascites is confined to the upper abdomen, unlike ascites, which is diffuse.

-

With ascites, the hyperechoic outer margin of the umbilical vein can be seen, as can the falciform ligament.

-

A small pericardial effusion (< 2 mm) is usually physiologic.

-

Left: Transverse section of the fetal abdomen. Right: Coronal section of the fetal thorax. These sonograms show ascites (asterisk) and echogenic lungs (L). This fetus had tracheal atresia. The red arrows indicate skin edema.

-

Coronal (left) and axial (right) fetal sonograms obtained late in the second trimester. These images show a large pleural effusion. The parents were from the Far East, and an earlier pregnancy had ended because of α thalassemia, which is a major cause of nonimmune-related hydrops fetalis in the Far East. The condition is uniformly fatal and associated with a significant risk of maternal morbidity. The α thalassemia gene is found in 20-30% of the population in Southeast Asia. The fetus was lost within 1 week of the ultrasonographic examination. Eff. = effusion; F. liver = fetal liver.

-

Coronal sonograms show a collapsed lung (arrows) as a result of a large pleural effusion.

-

Sonograms show scalp edema (S) (left) and edema of the thoracic wall (T) (right).

-

Sonograms shows limb edema (L) (left) and thoracic wall edema (T) (right).

-

Sonogram depicting gross skin edema involving the legs. The asterisks indicate edema of the lower ends of the thighs. F = femur.

-

Transverse sections of the fetal abdomen. These sonograms show small ascites (asterisk) and gross skin edema (red arrows).

-

Sonogram depicting crocodile skin in a fetus. This condition is a normal finding in some fetuses; the folded, apparently thickened skin (red arrows) can be confused with skin edema.

-

Transverse sonogram of a normal fetal head. The hair is visible as an irregular halo and can cause confusion with scalp edema.

-

Plain radiograph of the chest and abdomen of a neonate. This image shows a markedly distended abdomen with centrally located bowel loops that are suggestive of ascites. The soft tissues are edematous although the lung fields are clear.

-

Transverse ultrasonographic sections of the head (left) and chest (right) of a fetus with hydrops fetalis. Note the halo around the head; this is due to edema. Compare the halo with pseudoedema due to fetal hair. The chest shows gross skin edema and a large, bilateral pleural collection.