Practice Essentials

Hiatal hernia (also called hiatus hernia and paraesophageal hernia) occurs when part of the stomach protrudes into the thoracic cavity through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. Embryologic development of the diaphragm is a complex process; a number of defects result in a variety of possible congenital hernias through the diaphragm. A hernia may occur through a congenitally large esophageal hiatus; however, acquired hernias through the esophageal hiatus are more common. Traditionally, these hiatus hernias were classified either as sliding hernias or paraesophageal hernias (see the images below). The anatomic classification of hiatal hernias has evolved to further differentiate paraesophageal hiatal hernias. This type 3 hiatal hernia has mixed features of both sliding and paraesophageal hernias. [1] Approximately 99% of hiatal hernias are sliding, and the remaining 1% are paraesophageal. [2, 3, 4]

Most hiatal hernias are found incidentally, and they are usually discovered on routine chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scans performed for unrelated symptoms. When symptomatic, patients may experience heartburn, dyspepsia, or epigastric pain. Rarely, the patient may present with recurrent chest infections resulting from aspiration of gastric contents. A paraesophageal or, rarely, a sliding hiatal hernia may present acutely because of a volvulus or strangulation. Paraesophageal hernias are particularly likely to incarcerate and cause symptoms of intermittent epigastric pain. Barrett esophagus is commonly associated with hiatal hernia; patients with Barrett esophagus may present with reflux symptoms or dysphagia. [5, 6]

Hiatal hernias are classified into 4 types [2] :

-

Type I, or sliding, account for more than 95% of hiatal hernias and occurs when the gastroesophageal junction is displaced upward toward the hiatus.

-

Type II is paraesophageal hiatal hernia, which occurs when part of the stomach migrates into the mediastinum parallel to the esophagus.

-

Type III is a combination of paraesophageal hernia and sliding hernia, with both the gastroesophageal junction and a portion of the stomach migrating into the mediastinum.

-

Type IV is when the stomach and another organ, such as the colon, small intestine, or spleen, herniate into the chest.

Although paraesophageal hernias are uncommon, they are potentially life-threatening because of the risk of volvulus and incarceration. Symptoms include chest pain, abdominal pain, and respiratory distress. Symptomatic paraesophageal hernias require surgical repair, which is usually performed laparoscopicaly. [7]

The incidence of a hiatal hernia increases with age. When the lower esophageal sphincter is located within the thorax, its reinforcement of the diaphragmatic crus is loosened and allows gastroesophageal reflux of acid contents; such reflux may be symptomatic of hiatal hernia in 25% of patients because of reflux esophagitis. [8, 9]

Krim and associates highlighted the predisposing factors, mechanism, and different types of volvulus, as well as the role of imaging in making the diagnosis. Eventration of the diaphragm and hiatal hernia are precipitating factors for developing organoaxial and mesenteroaxial volvulus. The authors emphasize the role of imaging in making the diagnosis and distinguishing the types of volvulus to aid further management. [10]

Imaging modalities

Plain chest radiographs may demonstrate a retrocardiac gas-filled structure. An upper GI barium series is the preferred examination in the investigation of suggested hiatal hernia and its sequelae. CT scans are useful when more precise cross-sectional anatomic localization is desired. The use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and radionuclide studies is anecdotal. MRI is not routinely used in the diagnosis of a hiatal hernia, and it offers no advantages over the dynamic capability of an upper GI barium series. MRI has helped to achieve a diagnosis of a paraesophageal omental hernia, in which a retrocardiac mass was shown as a fatty tumor, with contiguous blood vessels extending from the abdominal portion into the thoracic portion. Theoretically, conditions mimicking hiatal hernia on CT scans can mimic hiatal hernia on MRIs. Ultrasonography is a sensitive means of diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux, and it is particularly attractive for use in young patients because it is noninvasive and does not require the use of ionizing radiation. [4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

Manometry studies have shown that it can be used to rule out motility disorders such as achalasia, which can mimic reflux. In some cases, high-resolution manometry provided an accurate diagnosis of hiatal hernia. [20, 21, 2]

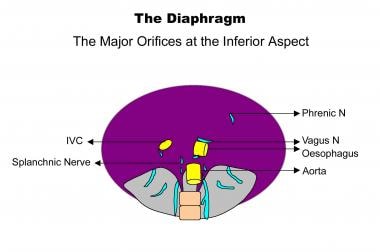

A diagram showing the 3 major orifices at the inferior aspect of the diaphragm (inferior vena cava [IVC], esophagus, aorta).

A diagram showing the 3 major orifices at the inferior aspect of the diaphragm (inferior vena cava [IVC], esophagus, aorta).

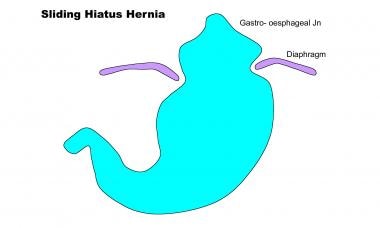

A diagram depicting a sliding hiatal hernia. The gastroesophageal junction (Jn) is located above the diaphragmatic hiatus.

A diagram depicting a sliding hiatal hernia. The gastroesophageal junction (Jn) is located above the diaphragmatic hiatus.

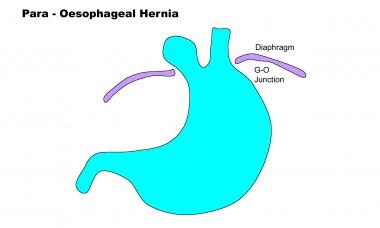

This diagram of a paraesophageal hiatal hernia shows the normal infradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

This diagram of a paraesophageal hiatal hernia shows the normal infradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

Limitations of techniques

The findings in an upper GI barium series may be specific, although the images may fail to demonstrate a small sliding hiatal hernia. Since gastroesophageal reflux may be intermittent, its presence may be overlooked. When no gas is present within the hernia, differentiating hernias from other retrocardiac masses may be difficult at times.

Making the diagnosis of hiatal hernia using ultrasonography is not always straightforward, and an intermittent hernia is likely to be missed; however, some physicians regard ultrasonography as the examination of choice in infants because the findings may differentiate duodenal causes of vomiting from esophageal causes.

Radiography

Most hiatal hernias are found incidentally on routine chest radiographs. The hernia may be seen as a retrocardiac mass with or without an air-fluid level. When air is seen within the hernia, the stomach air bubble found below the diaphragm tends to be absent. The hernia is usually positioned to the left of the spine; however, larger hernias (particularly incarcerated hernias) may extend beyond the cardiac confines and even mimic cardiomegaly. Most of these large hernias contain an air-fluid level and gastric contents.

An air-fluid level may be absent in the hernia on supine radiographs; occasionally, differentiation from other retrocardiac masses may be difficult by using supine radiographs.

(Radiographs of hiatal hernias are depicted in the images below.)

A plain chest radiograph showing a well-defined, rounded, soft-tissue mass in the retrocardiac region consistent with a sliding hiatal hernia.

A plain chest radiograph showing a well-defined, rounded, soft-tissue mass in the retrocardiac region consistent with a sliding hiatal hernia.

A frontal chest radiograph in a patient with a large hiatal hernia demonstrating a retrocardiac opacity with radiolucent gas, which shifts the mediastinum to the right.

A frontal chest radiograph in a patient with a large hiatal hernia demonstrating a retrocardiac opacity with radiolucent gas, which shifts the mediastinum to the right.

A lateral chest radiograph showing a hiatal hernia. Note the absence of fundal gas below the left hemidiaphragm.

A lateral chest radiograph showing a hiatal hernia. Note the absence of fundal gas below the left hemidiaphragm.

A chest radiograph in a patient with a huge air-filled hiatal hernia, which appears as a mediastinal mass.

A chest radiograph in a patient with a huge air-filled hiatal hernia, which appears as a mediastinal mass.

Upper GI barium series

An upper GI barium series is the definitive method of diagnosing hiatal hernias (see the image below). A single-contrast barium swallow performed with the patient in the prone position is more likely to demonstrate a sliding hiatal hernia than an upright double-contrast examination. On double-contrast examination, areae gastricae can be recognized within the intrathoracic stomach.

A barium-meal examination in a patient with a sliding hiatal hernia that demonstrates the supradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

A barium-meal examination in a patient with a sliding hiatal hernia that demonstrates the supradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

If the mucosal B ring is more than 1-2 cm above the diaphragmatic impression, a sliding hiatal hernia is present. A sliding hiatal hernia may also be diagnosed by recognizing 5 or more mucosal folds that are more than 1-2 cm above the diaphragm on a single-contrast barium examination. A sliding hiatal hernia is reducible with the patient in an erect position.

The hernia can often be recognized by the demonstration of mucosal gastric folds within the hernia. A hiatal hernia may cause deformity of the esophagus and/or fundus of the stomach. A tortuous esophagus may have an eccentric junction with the hernia.

On a dynamic study, the esophageal peristaltic wave ceases above the hiatus; thus, the end of a peristaltic wave delineates the esophagogastric junction.

An incarcerated hiatal hernia is believed to be present when a hernia remains fixed within the thorax and becomes irreducible.

With a paraesophageal or rolling hernia, part of the stomach rolls into the thorax; usually, this occurs anterior to the esophagus. The hernia is frequently irreducible. A paraesophageal hiatal hernia is diagnosed by the position of the gastroesophageal junction. The cardia of the stomach-esophagogastric junction usually remains in the normal position below the diaphragmatic hiatus, and only the stomach herniates into the thorax, adjacent to the normally placed gastroesophageal junction. A double-contrast examination occasionally depicts an ulcer on the lesser curve of the stomach. Paraesophageal hernia is not usually associated with gastroesophageal reflux.

A totally intrathoracic stomach is not a true hiatal hernia because herniation occurs through a defect in the central tendon of the diaphragm. The hernia is readily apparent on a single- or double-contrast barium swallow. The cardia is usually intrathoracic but it may occasionally be subdiaphragmatic. The greater curve of the stomach may lie either on the right or on the left.

Gastroesophageal reflux or esophagitis often accompanies a hiatal hernia, and it may be depicted effectively on barium swallow scans.

Degree of confidence

An upper GI barium series or barium swallow study is the examination of choice for depicting a hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux, and any associated complications.

A small sliding hiatal hernia may be missed by using a barium swallow or meal study. Other types of acquired or congenital diaphragmatic hernias, duplication cysts, neuroenteric cysts, neurogenic tumors, and the causes of paraspinal widening of soft tissues around the lower dorsal spine can all mimic the appearance of a hiatal hernia on plain radiographs.

Computed Tomography

CT scanning is not routinely used in the diagnosis of a hiatal hernia, but it may be useful for specific indications. CT scanning is particularly useful in the accurate anatomic depiction of a totally intrathoracic stomach, especially in patients in whom volvulus of the stomach is suspected. CT scanning is also useful for staging purposes in patients in whom a carcinoma complicates a hiatal hernia. Dehiscence of diaphragmatic crura of more than 15 mm may be seen. Hiatal hernias often are seen incidentally on CT scans obtained for other indications (see the image below). A hiatal hernia appears as a retrocardiac mass with or without an air-fluid level. The mass can usually be traced into the esophageal hiatus on sequential cuts. Herniation of omentum through the esophageal hiatus may result in an increase in fat surrounding the lower esophagus. [6, 22]

An axial CT scan of the thorax in a 75-year-old woman showing a retrocardiac mediastinal mass with a fluid level caused by a hiatal hernia.

An axial CT scan of the thorax in a 75-year-old woman showing a retrocardiac mediastinal mass with a fluid level caused by a hiatal hernia.

Ultrasonography

In individuals without hiatal hernia, the gastroesophageal junction can almost always be depicted on ultrasonography with a cross-sectional diameter of 7.1-10.0 mm at the diaphragmatic hiatus level. The gastroesophageal junction is not depicted in a hiatal hernia, and the bowel diameter measured at the diaphragmatic hiatus is 16.0-21.0 mm. Each of the aforementioned signs has a predictive value of 100%. The negative predictive value of the bowel diameter is 90%, and failure to depict the gastroesophageal junction has a negative predictive value of 94.7%.

Sliding hiatal hernia in children

Signs of a sliding hiatal hernia in infants and young children include the following: intra-abdominal esophagus measuring less than 2 cm, rounding of the gastroesophageal angle, and the presence of a beak at the gastroesophageal junction. [12]

Gastroesophageal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux may be sonographically diagnosed with 95% sensitivity, but reflux is an intermittent phenomenon, and prolonged scanning times may be required, which may not always be practical. To detect reflux, the patient must also be positioned so that fluid is lying over the gastroesophageal junction. The examination may start with the patient lying in the supine position, but raising the left side or even placing the patient in a head-down position may be necessary to allow reflux to occur.

On sonograms, fluid refluxing into the lumen of the esophagus is seen as an anechoic column. With slight reflux, the column is small, transient, and easily missed. In more severe reflux, the column of fluid is long and may persist for some time. The fluid often contains small echogenic air bubbles caused by turbulent flow. With care, the accuracy of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux is similar to the accuracy of a barium meal examination.

Persistent vomiting in infants

Ultrasonography of the abdomen is an accurate and rapid screening method that can be used to differentiate the causes of persistent vomiting in infants; the findings can reliably help differentiate esophageal from duodenal causes. A test feeding is usually given, followed by ultrasonography. The examination is focused on the duodenum to document or exclude pyloric stenosis. Once pyloric stenosis has been excluded, attention is paid to the gastroesophageal junction to detect reflux, hiatal hernia, or both. [12]

Degree of confidence

Ultrasonography is a noninvasive technique that may be useful in the diagnosis of a hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux. The use of ultrasonography is an attractive option in infants and young children in whom the images can help in differentiating esophageal causes of vomiting from duodenal causes.

The predictive value of the criteria used in the evaluation of a sliding hiatal hernia in infants and young children is quite good; however, the criteria cannot be applied if the gastric fundus distal to the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction no longer lies within the abdominal cavity. One of the disadvantages of using ultrasonography for evaluating reflux is that sonograms poorly depict the severity of reflux, and sonograms are not sensitive for depicting esophagitis. An associated hiatal hernia, however, can be detected reliably.

Nuclear Imaging

Radionuclides are not routinely used for the diagnosis of a hiatal hernia, but hiatal hernias may be incidentally found on whole-body radioiodine surveys performed in patients with thyroid cancer, in whom hernias may mimic metastatic cancer. Similarly, technetium-99m (99mTc) pertechnetate and other 99mTc-labeled isotopes may depict a hiatal hernia incidentally. Oral 99mTc sulfur colloid scans and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) images may help in differentiating a hiatal hernia from metastatic thyroid cancer.

Duodenogastric reflux in a hiatal hernia can be seen as retrocardiac activity on 99mTc-tetrofosmin cardiac SPECT raw-data images. Incidental findings such as extracardiac and retrocardiac activity in the thorax and abdomen should be included on all comprehensive cardiac SPECT reports. [22]

Theoretically, a duplication cyst or a neuroenteric cyst containing gastric mucosa may take up radioiodine or 99mTc compounds.

There have been reports of a hiatal hernia showing thoracic uptake of iodine-131 on scintigraphy, mimicking a pulmonary or mediastinal metastasis. [23]

Angiography

Hiatal hernia and esophagitis rarely produce massive GI tract hemorrhage; however, if this occurs, angiography may be able to depict the site of GI tract hemorrhage and the feeding blood vessels.

Experience with angiography in hemorrhage from a hiatal hernia is limited, and the degree of confidence with which the diagnosis can be made is unknown.

A false-negative diagnosis may occur if the gastric hemorrhage has temporarily stopped at the time of angiography (intermittent bleed) or if the rate of hemorrhage is slow. A false-positive diagnosis may occur when using digital subtraction angiography, as bowel movements can be erroneously interpreted as hemorrhage.

-

A diagram showing the 3 major orifices at the inferior aspect of the diaphragm (inferior vena cava [IVC], esophagus, aorta).

-

A diagram depicting a sliding hiatal hernia. The gastroesophageal junction (Jn) is located above the diaphragmatic hiatus.

-

This diagram of a paraesophageal hiatal hernia shows the normal infradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

-

A plain chest radiograph showing a well-defined, rounded, soft-tissue mass in the retrocardiac region consistent with a sliding hiatal hernia.

-

A frontal chest radiograph in a patient with a large hiatal hernia demonstrating a retrocardiac opacity with radiolucent gas, which shifts the mediastinum to the right.

-

A lateral chest radiograph showing a hiatal hernia. Note the absence of fundal gas below the left hemidiaphragm.

-

A barium-meal examination in a patient with a sliding hiatal hernia that demonstrates the supradiaphragmatic location of the gastroesophageal junction.

-

A frontal chest radiograph in a 75-year-old woman with a hiatal hernia that demonstrates an air-fluid level.

-

An axial CT scan of the thorax in a 75-year-old woman showing a retrocardiac mediastinal mass with a fluid level caused by a hiatal hernia.

-

A chest radiograph in a patient with a huge air-filled hiatal hernia, which appears as a mediastinal mass.

-

An abdominal radiograph in a patient with a huge air-filled hiatal hernia. This radiograph, obtained on the day after the previous image was obtained, shows acute gastric dilatation caused by an incarcerated hiatal hernia.