Practice Essentials

Peptic ulcers are mucosal breaks of 3 mm or greater and are common, occurring in about 10% of adults in Western countries. [1] Gastric ulcers account for about one third of peptic ulcers, and duodenal ulcers account for the remainder. Because a small percentage (< 5%) of gastric ulcers are caused by ulcerated gastric carcinomas, all gastric ulcers must be carefully assessed to differentiate benign lesions from malignant lesions. With the decline of Helicobacter pylori infection, the detection of idiopathic peptic ulcer disease has become more frequent, making diagnosis and treatment more difficult. [2, 3]

Preferred examination

Fiberoptic endoscopy of the upper GI tract has become the diagnostic procedure of choice for patients with suspected duodenal ulcer. However, endoscopic examinations are more invasive and costly than double-contrast barium studies. [4] Endoscopy with biopsy has a sensitivity of 95%, [1] but multiple biopsy samples are needed to avoid sampling errors. [5, 6]

The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has published guidelines regarding endoscopy in patients with upper abdominal pain or dyspeptic symptoms that suggest peptic ulcer disease. The ASGE suggests that the decision to perform surveillance endoscopy in patients with a gastric ulcer be individualized. Surveillance endoscopy is suggested for patients with gastric ulcer who remain symptomatic despite an appropriate course of medical therapy. They note that it should also be considered in patients with gastric ulcers without a clear etiology and in patients who did not undergo biopsy at the index esophagogastroduodenoscopy [7, 8]

Savarino et al reported success with narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy in detecting gastric intestinal metaplasia. [5] Hancock et al studied the benefits of i-scan software, which allows modifications of sharpness, hue, and contrast, thereby enhancing mucosal imaging; they studied 20 patients undergoing endoscopy of the GI tract and concluded that i-scan imaging provides detailed information about mucosal surfaces and delineates lesion edges. [6]

Single-contrast barium studies have an overall sensitivity of 75%, but double-contrast barium examinations have a sensitivity as high as 95% in the detection of gastric cancer. [1] These results are comparable to those of endoscopy, and double-contrast barium examination remains a useful alternative to endoscopy. However, barium studies have a disadvantage in that biopsy specimens of the lesion cannot be obtained to test for Helicobacter pylori infection (an important factor in gastric ulcer development) or to evaluate for the presence of malignancy.

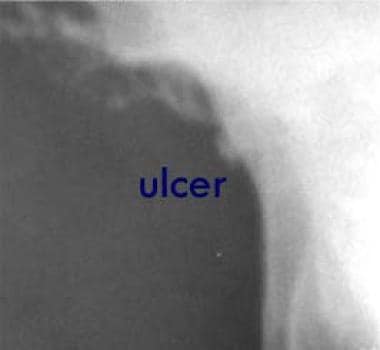

(Radiologic characteristics of gastric ulcers are seen in the images below.)

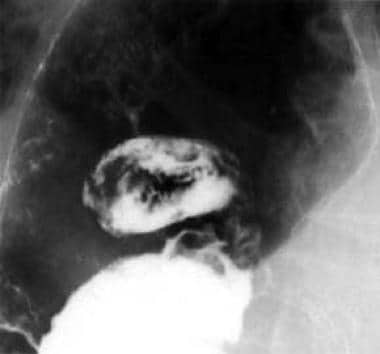

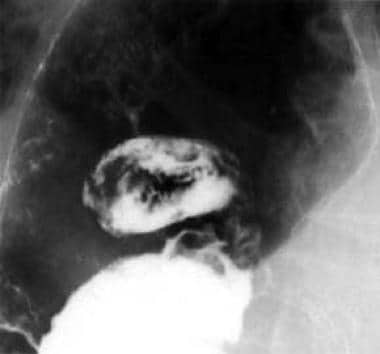

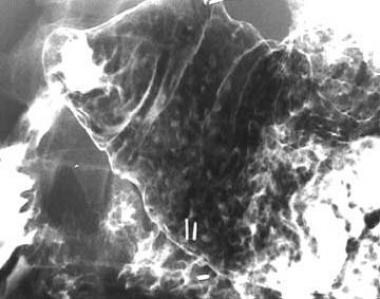

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

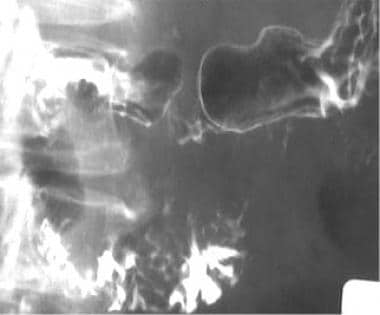

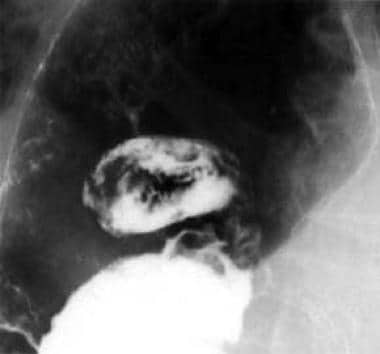

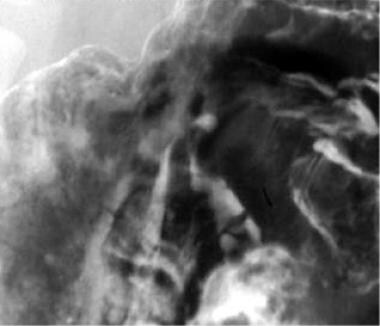

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

The World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) recommends the following for acute abdomen from suspected perforated peptic ulcer [9] :

-

CT scanning.

-

Chest/abdominal radiograph as the initial routine diagnostic assessment in case a CT scan is not promptly available.

-

When free air is not seen on imaging and there is ongoing suspicion of perforated peptic ulcer, imaging with the addition of water-soluble contrast either orally or via nasogastric tube.

Although endoscopy remains the standard of care, multidetector CT (MDCT) may prove useful in patients with suspected gastroduodenal bleeding. [10, 11, 12, 13]

Hemorrhage

Hemorrhage occurs in 20-30% of ulcers. [1] Endoscopy is the modality of choice for the investigation of hemorrhages, having a sensitivity of more than 90% in the detection of the bleeding site.

The American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria include the following imaging recommendations for identifying the source of upper GI bleeding (UGIB) [14] :

-

When endoscopy identifies the presence and location of bleeding but bleeding cannot be controlled endoscopically, catheter-based arteriography with treatment is an appropriate next study. CT angiography (CTA) is comparable to angiography as a diagnostic next step.

-

If endoscopy demonstrates a bleed but the endoscopist cannot identify the bleeding source, angiography or CTA can be typically performed, and both are considered appropriate.

-

In the event of an obscure UGIB, angiography and CTA have been shown to be equivalent in identifying the bleeding source; CT enterography may be an alternative to CTA to find an intermittent bleeding source.

-

In the postoperative or traumatic setting when endoscopy is contraindicated, primary angiography, CTA, and CT with IV contrast are considered appropriate.

Double-contrast barium studies are limited by poor mucosal coating in the presence of bleeding. Nevertheless, the bleeding site may be detected in as many as 75% of cases. A filling defect caused by a blood clot may be seen at the base of the barium-filled ulcer (as seen in the images below).

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

Perforation

Perforation occurs in as many as 10% of patients with peptic ulcer disease but is less common in gastric ulcers. [1]

Most perforations arise from ulcers in the anterior aspect of the duodenal cap and, less commonly, from the anterior aspect of the lesser curve of the stomach.

In 75% of cases, free gas is present in the peritoneum; this is best shown on an erect chest radiograph (as demonstrated in the first image below) rather than on an erect or supine abdominal radiograph.

An upper GI series performed with water-soluble contrast agent may demonstrate the presence and site of the perforation and whether it has sealed.

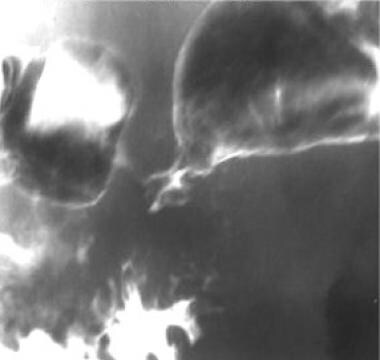

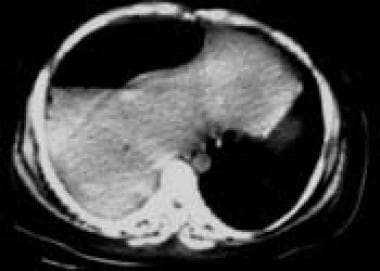

Subphrenic collections are common sequelae of a perforated peptic ulcer. They may be depicted on plain radiographs (see the first image below), but they are best assessed with ultrasonography [15, 16] or computed tomography (CT) scanning (see the second image below).

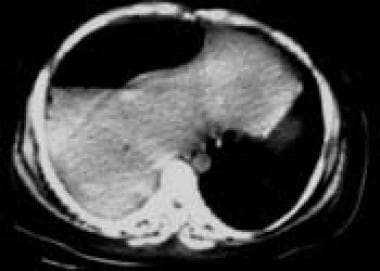

Computed tomography scan. Subphrenic collection with gaseous and liquid components. Note the interface between the edge of the liver and the collection.

Computed tomography scan. Subphrenic collection with gaseous and liquid components. Note the interface between the edge of the liver and the collection.

Radiography

The biphasic technique of double-contrast barium study combines double-contrast views of the stomach obtained using effervescent granules and a high-density barium suspension with subsequent prone or erect single-contrast compression views obtained using a low-density barium suspension. Glucagon 0.1 mg is administered intravenously as a hypotonic agent. Ulcers in the posterior wall or lesser curve are depicted well on double-contrast supine or oblique views. However, prone compression views are required to visualize anterior wall ulcers because they do not fill on supine or oblique projections.

Single-contrast views have a sensitivity of about 75%, and the combined double-contrast technique has a sensitivity of 95%. [1]

Radiologic features of gastric ulcers

Gastric ulcers are usually seen as round or ovoid collections of barium (see the images below), but they can also be linear or rod or star shaped. Linear ulcers are often observed in the healing stages.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 1-cm lesser-curve ulcer is depicted en face. Note the radiating mucosal folds.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 1-cm lesser-curve ulcer is depicted en face. Note the radiating mucosal folds.

Ulcers smaller than 5 mm may not be detected on barium studies. The availability of effective medical therapy, commenced before barium study, has been associated with a prevalence of ulcers smaller than 10 mm. Ulcers may vary from 3 mm to less than 5 cm in diameter. Giant ulcers (>3 cm) have a greater risk of complications, such as bleeding and perforation (see the first 2 images below). A gastric diverticulum, which usually arises from the posterior wall of the fundus (see the third image below), should not be confused with a large ulcer.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

Most benign ulcers are located in the lesser curve or posterior wall of the antrum or body of the stomach. Only about 5% of benign ulcers are located in the anterior wall or greater curve. Antral ulcers are seen in younger patients and upper lesser-curve ulcers are seen in the elderly. [1]

Detection of multiple gastric ulcers varies with the imaging technique: single-contrast studies, 2-8%; double-contrast studies, about 20%; and endoscopy, as high as 30%. [1] Multiple ulcers are more common in patients using aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Multiple gastric ulcers are usually located in the antrum or body.

Lesser-curve ulcers

The smooth, round, or oval ulcer crater projects beyond the contour of the adjacent gastric wall. Areae gastricae adjacent to the ulcer may be enlarged because of edema, and undermining of the mucosa in the base of the ulcer results in the appearance of a thin, radiolucent line called the Hampton line, dividing the barium in the ulcer crater from that in the body of the stomach. If the rim of mucosa becomes edematous, a wider radiolucent band or ulcer collar may be observed. Less commonly, the edema and swelling around the ulcer may produce an ulcer mound with poorly defined outer borders.

Hampton lines, ulcer collars, and ulcer mounds are classic features of benign gastric ulcers, but they are observed in only a minority of lesser-curve ulcers. Retraction of the gastric wall adjacent to the lesser-curve ulcers may lead to the formation of smooth, symmetrical folds that radiate from the ulcer crater. The opposite wall may also be retracted, producing an incisura of the greater curve and, ultimately, an hourglass stomach.

(See the images below.)

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows a small lesser-curve ulcer with regular radiating mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed no evidence of malignancy.

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows a small lesser-curve ulcer with regular radiating mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed no evidence of malignancy.

Hourglass deformity caused by fibrosis. This large lesser-curve ulcer is healing, with fibrosis dividing the body of the stomach into 2 compartments.

Hourglass deformity caused by fibrosis. This large lesser-curve ulcer is healing, with fibrosis dividing the body of the stomach into 2 compartments.

Greater-curve ulcers

Benign greater-curve ulcers are usually located in the distal half of the stomach and are strongly associated with aspirin and NSAID use; the dissolving aspirin tablets collect in the most dependent part of the stomach and cause focal ulceration and gastric erosions (as demonstrated in the image below).

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows aspirin-induced gastric erosions in the body and antrum.

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows aspirin-induced gastric erosions in the body and antrum.

The ulceration and erosions may appear intraluminal because of associated muscle spasm and retraction of the adjacent gastric wall and are usually associated with thickened irregular folds and edema. An upper greater-curve ulcer suggests malignancy. Endoscopy and biopsy are required to exclude malignancy.

Posterior wall ulcers

Posterior wall ulcers may fill with barium and have the typical appearance of an ulcer crater; shallow ulcers may appear as ring shadows.

The surrounding mucosa is best assessed with en face views; the areae gastricae may be enlarged because of edema, and an ulcer collar is seen as a radiolucent halo surrounding the ulcer. Mucosal folds may radiate from the ulcer crater.

Anterior wall ulcers

Anterior wall ulcers are depicted as ring shadows; barium coats the rim of the unfilled ulcer crater. These ulcers fill in when the patient is in the prone position.

Pyloric channel ulcers

Most pyloric channel ulcers (seen in the images below) are smaller than 1 cm in diameter and are located in the lesser-curve aspect or anterior wall of the pylorus.

These ulcers may be associated with marked edema and spasm of the pylorus and distal antrum and may resemble an ulcerated carcinoma. New ulcers must be differentiated from pseudodiverticula caused by scarring from previous ulcers; mucosal folds are present in pseudodiverticula but not in ulcers. Healing of pyloric channel ulcers may lead to gastric outlet obstruction as a result of scarring and narrowing or angulation of the pyloric canal.

Appearances suggestive of a benign ulcer

About 95% of gastric ulcers are benign. [1] The double-contrast technique allows differentiation between benign and malignant gastric ulcers in most cases.

Features associated with a benign ulcer include projection of the ulcer beyond the healthy lumen on the profile view. The margin of the ulcer crater is sharply defined and smooth en face. Any filling defect that surrounds the ulcer, as a result of edema, is smooth and symmetrical and merges with the healthy mucosa. The mucosal folds radiate to the edge of the ulcer.

Benign ulcers that do not have these typical features are classified as indeterminate, and endoscopy and biopsy are required, as they are for ulcers that appear malignant. Reports of single-contrast studies before 1975 showed that 6-16% of gastric ulcers with benign appearances were actually malignant. [17] This finding accounts for the common practice of performing endoscopy and biopsy for gastric ulcers that appear benign despite the low incidence of malignancy (5%). [1]

Appearances suggestive of malignancy

Features associated with a malignant ulcer include an intraluminal location for the ulcer crater. Exceptions are ulcers in the antrum or greater curve, where benign ulcers are often drawn inward because of muscle spasm in the adjacent stomach wall.

The crater margins of a malignant ulcer may be irregular and nodular, and the ulcer crater is surrounded by an asymmetrical mass that has an abrupt outer border with the healthy mucosa. In addition, clubbed mucosal folds terminate short of the ulcer crater. (See the image below.)

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows gastric ulceration with coarse irregular mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed an adenocarcinoma.

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows gastric ulceration with coarse irregular mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed an adenocarcinoma.

Ulcers in the fundus are rare, and almost all are malignant.

Ulcer healing and scarring

Ulcer healing is demonstrated at follow-up as a decrease in ulcer size and, often, a change in shape from round to linear. Complete healing or disappearance of the ulcer is usually observed 8 weeks after medical treatment and confirms its benign nature. Endoscopy and biopsy are indicated if any residual nodularity or irregularity is present.

Posterior wall ulcers are often associated with radiating mucosal folds that converge to form a shallow pit. This appearance may be mistaken for an ulcer crater; however, its margins slope more gradually than that of an ulcer crater, and its appearance does not change on follow-up images.

Healing of antral ulcers is associated with narrowing and deformity that may mimic malignancy. The hourglass stomach results from the healing of a lesser-curve ulcer and marked retraction or deformity of the opposite wall.

Computed Tomography

CT scanning has no part in the primary detection of gastric ulcers; however, this modality has a role in the detection of subphrenic and other collections that may occur after a perforation of a gastric ulcer. [18, 19, 20, 21]

(See the image below.)

Computed tomography scan. Subphrenic collection with gaseous and liquid components. Note the interface between the edge of the liver and the collection.

Computed tomography scan. Subphrenic collection with gaseous and liquid components. Note the interface between the edge of the liver and the collection.

Direct signs of peptic ulcer disease on cross-sectional imaging include focal discontinuity of the mucosal hyperenhancement and identification of luminal outpouching. A useful indirect sign, which alerts to possible active inflammation and/or peptic ulcer, is edematous stranding of the periduodenal fat. [10]

Cross-sectional imaging is useful for depicting complications of duodenal ulcers, with bleeding the most common complication. Ectopic gas, periduodenal fluid, wall thickening, or contrast material within the periduodenal fat or lesser sac are signs suggesting perforation. [11]

Multidetector row CT (MDCT) scanning [21] and three-dimensional (3D) imaging are expected to overcome the limitations in cancer staging by offering rapid and accurate information for space perception, detailed hemodynamics, and real-time 3D processing of volumetric data sets. In particular, virtual endoscopic imaging may be helpful for detecting early gastric cancer.

-

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 5-cm ulcer crater in the lesser curve of the stomach is depicted en face. The filling defects in the ulcer crater are caused by a blood clot from recent bleeding.

-

This lateral view (same patient as in the previous image) shows poor mucosal coating caused by recent bleeding.

-

This erect chest radiograph shows free gas under the diaphragm from a perforated gastric ulcer.

-

This supine abdominal radiograph shows a pneumoperitoneum.

-

This radiograph depicts a subphrenic collection resulting from a perforated gastric ulcer.

-

Computed tomography scan. Subphrenic collection with gaseous and liquid components. Note the interface between the edge of the liver and the collection.

-

Image from an upper gastrointestinal series. A 1-cm lesser-curve ulcer is depicted en face. Note the radiating mucosal folds.

-

This image shows a small lesser-curve gastric ulcer in profile.

-

A 1.5-cm ulcer is depicted en face in the lesser curve of the stomach.

-

Large gastric diverticulum in the fundus.

-

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows a small lesser-curve ulcer with regular radiating mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed no evidence of malignancy.

-

Hourglass deformity caused by fibrosis. This large lesser-curve ulcer is healing, with fibrosis dividing the body of the stomach into 2 compartments.

-

Another image obtained in the same patient as in the previous image.

-

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows aspirin-induced gastric erosions in the body and antrum.

-

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows a pyloric canal ulcer.

-

This image shows a pyloric canal ulcer in detail.

-

This image from an upper gastrointestinal series shows gastric ulceration with coarse irregular mucosal folds. Histologic evaluation revealed an adenocarcinoma.