Practice Essentials

Pediatric emergency department (ED) visits due to ingestion of a foreign body are common, with the majority of cases ocurring in children younger than 4 years. [1, 2, 3] Up to 80% of all cases of esophageal foreign bodies occur in children aged 6 months to 3 years. The most common site is the cricopharynx. From 80 to 90% of foreign bodies pass through the GI tract without consequence, 10-20% require removal by endoscopy, and less than 1% require surgery. [4, 2] The increase in the use of higher-voltage button batteries and powerful magnets in toys has increased the number of accidental ingestions. [5] Prompt treatment of an infant or child with a suspected esophageal foreign body is crucial because of the potential for severe complications.

A study of 415 button battery ingestions identified the following 9 symptoms associated with severe effects and death [6] :

-

Dyspnea

-

Cough

-

Dysphagia

-

Drooling

-

Fever

-

Hemodynamic instability

-

Pain

-

Pallor

-

Vomiting.

Radiographic evaluation of the esophageal foreign body is warranted in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Ingestions that are witnessed are generally managed without problems. Conversely, diagnosis of nonwitnessed ingestions can often be difficult and delayed. This delay in diagnosis can result in severe morbidity and mortality. [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

(See the images below.)

Anteroposterior chest radiograph depicts a penny at the thoracic inlet of a 13-month-old infant who refused to eat.

Anteroposterior chest radiograph depicts a penny at the thoracic inlet of a 13-month-old infant who refused to eat.

Lateral chest radiograph (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) depicts soft-tissue thickening at the tracheoesophageal interface. A penny was removed at esophagoscopy.

Lateral chest radiograph (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) depicts soft-tissue thickening at the tracheoesophageal interface. A penny was removed at esophagoscopy.

Imaging modalities

The radiographic evaluation begins with the acquisition of anteroposterior and lateral chest, anteroposterior and lateral neck, and supine abdominal radiographs to complete the examination from the nasopharynx to the rectum. [12, 18, 19, 20]

If a child is referred from an outside institution, a repeat chest radiograph can be obtained to reconfirm the presence of the foreign body in the esophagus or confirm its passage beyond the esophagus, obviating a retrieval procedure. [21]

If the presence of a nonradiopaque object is suspected after the initial series of radiographs is obtained, contrast-enhanced esophagography is indicated to rule out a radiolucent foreign body. Further evaluation with cross-sectional imaging may be required to determine the presence and extent of mediastinitis versus mediastinal abscess formation. [22, 23]

The major limitation of the initial plain radiographic evaluation is the potential failure to visualize the nonradiopaque foreign body. Small esophageal foreign bodies, such as button batteries, may also be difficult to visualize on plain radiographs alone. [11] Additional evaluation is required when the suspected foreign body is not radiopaque or when the presence of a retained object is highly suspected. The initial radiographic evaluation also can cause underestimation of the extent or degree of involvement, such as the amount of edema with foreign bodies that are retained for long periods.

Contrast-enhanced CT should be performed if the plain radiograph is negative, if the contrast-enhanced esophagographic findings are positive, or if there is still a high suspicion of an esophageal foreign body is.

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred cross-sectional imaging tool for evaluating the full extent of cervicothoracic masses and the relationships between neurovascular structures, it is not the initial imaging method of choice for the workup for a retained foreign body or traumatic lesion. However, MRIs can readily demonstrate the extent of a mediastinal inflammatory abscess or granuloma formation.

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) has published guidelines for ingested foreign bodies, including the following [24] :

-

Does not recommend radiologic evaluation for patients with nonbony food bolus impaction without complications. Recommends plain radiography to assess the presence, location, size, configuration, and number of ingested foreign bodies if ingestion of radiopaque objects is suspected or type of object is unknown.

-

Recommends CT scan for all patients with suspected perforation or other complication that may require surgery.

-

Does not recommend barium swallow because of the risk of aspiration and worsening of the endoscopic visualization

-

Recommends clinical observation without the need for endoscopic removal for management of asymptomatic patients with ingestion of blunt and small objects.

Radiography

The initial plain radiographic series is crucial in the diagnosis of an esophageal foreign body, because the location and characteristics of the esophageal foreign body are used to direct treatment. The most common site of foreign body lodgment is the upper esophagus at the level of the thoracic inlet. [12]

On the frontal chest radiograph, an opaque foreign body is depicted at the midclavicular level. A coin in the esophagus is depicted in the coronal plane of a frontal image because of the inherent configuration of the esophagus. If the coin is in the sagittal plane of the frontal image, the foreign body is most likely in the trachea. The orientation is generally caused by the incomplete circumferential cartilaginous rings along the posterior aspect of the trachea that allow the coin to protrude posteriorly. [18, 19]

If a circular coin-like object is seen on radiography, the radiologist should look for a halo or double-ring appearance, which indicates the presence of a button battery and therefore the need for emergent removal. A chest radiograph can differentiate coins from button batteries with a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of approximately 80%. [3]

(See the images below.)

Anteroposterior chest radiograph depicts a penny at the thoracic inlet of a 13-month-old infant who refused to eat.

Anteroposterior chest radiograph depicts a penny at the thoracic inlet of a 13-month-old infant who refused to eat.

Lateral chest radiograph (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) depicts soft-tissue thickening at the tracheoesophageal interface. A penny was removed at esophagoscopy.

Lateral chest radiograph (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) depicts soft-tissue thickening at the tracheoesophageal interface. A penny was removed at esophagoscopy.

The second most common site for esophageal foreign body retention is the level of the carina and aortic arch because of normal physiologic narrowing in the mid esophagus at this level. The third location is the distal esophagus slightly above the gastroesophageal junction. On the frontal chest radiograph, this location is approximately 3 vertebral body levels above the gastric air bubble. If a radiopaque foreign body is seen at another level, an underlying stricture should be suspected, and further investigation with contrast-enhanced esophagography is indicated.

The characteristics of the object (eg, radiopaque or radiolucent and sharp or blunt) and the number of retained items affect the choice of retrieval method. [25] Additional plain radiographic findings may include soft-tissue masses; these may represent inflammatory changes and possibly indicate a more chronic process.

Tracheal displacement or compression suggests mediastinal inflammation and airway compromise (see the images below). An air-fluid level suggests mediastinal abscess formation, whereas a pneumomediastinum may indicate an esophageal perforation.

Chest radiograph depicts deviation of the trachea to the right in an 18-month-old female infant with upper respiratory congestion lasting 3 months.

Chest radiograph depicts deviation of the trachea to the right in an 18-month-old female infant with upper respiratory congestion lasting 3 months.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the neck (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) demonstrates tracheal deviation to the right.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the neck (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) demonstrates tracheal deviation to the right.

Barium esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images) demonstrates irregularity along the anterior aspects of the barium column.

Barium esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images) demonstrates irregularity along the anterior aspects of the barium column.

Anteroposterior esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images) demonstrates irregularity of the contrast material column along the right lateral aspect of the esophagus. These findings suggest the presence of a nonradiopaque foreign body, and the patient was referred for further evaluation with CT.

Anteroposterior esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images) demonstrates irregularity of the contrast material column along the right lateral aspect of the esophagus. These findings suggest the presence of a nonradiopaque foreign body, and the patient was referred for further evaluation with CT.

If the presence of a nonradiopaque foreign body is suspected, contrast-enhanced esophagography is indicated. Positive findings on the esophagram include irregularity of the contrast medium column or esophageal mucosa, as well as deviation in the expected course of the esophagus. Underlying stricture formation, with or without proximal esophageal dilatation or diverticula formation caused by chronic esophageal perforation, may also be present.

Foreign bodies that migrate outside the esophagus into the mediastinum or soft tissues usually cause respiratory symptoms. Complete foreign body migration outside the esophagus is occult on esophagoscopic images, but it may be depicted on chest radiographs.

Computed Tomography

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning is indicated for the assessment of a suspected esophageal foreign body when the plain radiographic findings are negative, the contrast-enhanced esophagographic findings are positive, or the presence of an esophageal foreign body is highly suspected.

CT can aid in characterizing the nature of the foreign body, as well as the presence and extent of surrounding disease such as mediastinitis or abscess formation. Also, small foreign bodies that cannot be visualized with a standard radiologic examination can be evaluated with CT. Chicken and fish bones lodged in the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus are difficult to evaluate on plain radiographs. [26, 27, 28] CT is also valuable in the assessment of complications of foreign body removal. [13, 29, 14, 20] (See the image below.)

In a study by Woo and Kim, it was suggested that CT be considered a first-choice technique for the diagnosis of esophageal fish bone foreign body. In 88 patients studied with a history of fish bone impaction, 66 patients were discovered to have a fish bone foreign body in the esophagus by CT, as compared to 30 patients by plain radiography. [26]

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) has been found to be useful for the evaluation of pharyngeal and upper esophageal foreign bodies. In one study, the sensitivity of MDCT for the detection of foreign bodies was 100%, which was superior to that of plain radiography (51.7%). [27]

Multslice spiral CT (MSCT) has been found to accurately locate most foreign bodies, but dual-source CT (DSCT) uses a lower dose of radiation and and has higher resolution. [30]

-

Anteroposterior chest radiograph depicts a penny at the thoracic inlet of a 13-month-old infant who refused to eat.

-

Lateral chest radiograph (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) depicts soft-tissue thickening at the tracheoesophageal interface. A penny was removed at esophagoscopy.

-

Chest radiograph depicts deviation of the trachea to the right in an 18-month-old female infant with upper respiratory congestion lasting 3 months.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the neck (obtained in the same patient as in the previous image) demonstrates tracheal deviation to the right.

-

Barium esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 2 images) demonstrates irregularity along the anterior aspects of the barium column.

-

Anteroposterior esophagram (obtained in the same patient as in the previous 3 images) demonstrates irregularity of the contrast material column along the right lateral aspect of the esophagus. These findings suggest the presence of a nonradiopaque foreign body, and the patient was referred for further evaluation with CT.

-

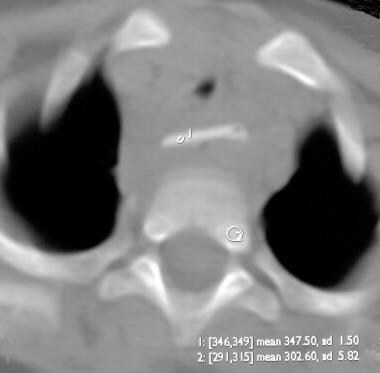

Nonenhanced axial CT scan demonstrates a retained esophageal foreign body. Its attenuation is similar to that of adjacent bone. Note the adjacent soft-tissue swelling and tracheal narrowing. At esophagoscopy, a metal-coated plastic disk was retrieved.

-

Radiograph in a 13-year-old girl who shortly before had been playing with jacks.

-

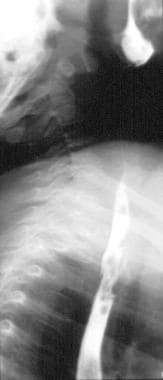

Oblique barium esophagram depicts pseudodiverticulum formation that required thoracotomy for repair in a patient who had persistent discomfort while eating (same patient as in the previous image).