Practice Essentials

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) describes a group of syndromes that share the common pathologic feature of infiltration of involved tissues by Langerhans cells. Typically, the skeletal system is involved, with a characteristic lytic bone lesion form that occurs in young children or a more acute disseminated form that occurs in infants. In adults, the skull is the most common site for LCH invovement. [1]

Pulmonary involvement is not unusual in systemic forms of LCH, but symptoms are rarely a prominent feature. [2, 3] Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis is considered a reactive proliferation of dendritic Langerhans cells to chronic tobacco-derived plant proteins resulting from incomplete combustion, but it can also occur as a tumor-like systemic disease in children. [4]

LCH can involve a single system or multisystems, including bone marrow, lungs, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, and pituitary gland, with prognosis depending on presentation and organ involvement. LCH can occur at any age but is most common from birth to 15 years. The clinical spectrum can range from an asymptomatic isolated skin or bone lesion to a life-threatening multisystem condition. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

In patients with suggested eosinophilic granuloma, obtain a chest radiograph and a chest high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan. [2, 13, 14] [3, 15, 16, 17] In HRCT scanning, the small star-like scars can still be detected even after complete cessation of tobacco smoking. [4]

Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-CT (FDG-PET-CT) is becoming the preferred imaging modality for diagnosis and assessment of response to therapy in LCH with bone involvement. [1, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]

Biopsy of the involved site (usually skin) is required. Lesions will stain positive for S-100 and CD-1a. Positive CD1a, S100, and/or CD207 (langerin) immunohistochemical staining provides a definitive diagnosis. These cells carry somatic mutations of the BRAF gene and/or NRAS, KRAS, and MAP2K1 genes. Granulomatous lesions containing langerin-positive (CD207+) histiocytes and an inflammatory infiltrate can be present in any organ system but have an affinity for bone, skin, the lungs, and the pituitary. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]

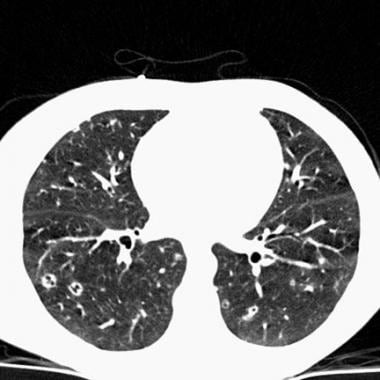

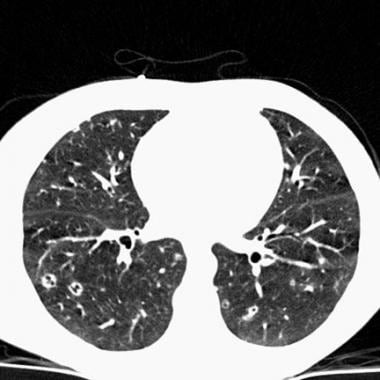

(CT scans of eosinophilic granuloma are depicted in the images below.)

Chest CT in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma demonstrates scattered cavitary and noncavitary nodules.

Chest CT in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma demonstrates scattered cavitary and noncavitary nodules.

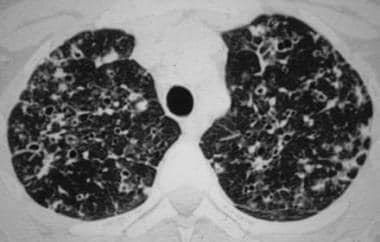

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows the typical combination of nodules, cavitated nodules, and thick- and thin-walled cysts. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows the typical combination of nodules, cavitated nodules, and thick- and thin-walled cysts. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

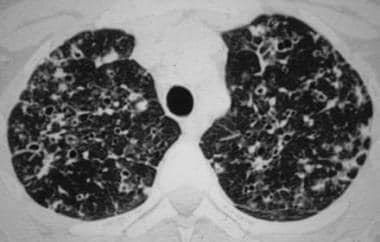

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with advanced pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows numerous pulmonary cysts of various sizes, which are confluent in some places. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with advanced pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows numerous pulmonary cysts of various sizes, which are confluent in some places. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

Localized pulmonary LCH (also termed pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma) is a rare pulmonary disease that occurs predominantly in young adults. The precise incidence and prevalence of pulmonary LCH are unknown, although studies of lung biopsy specimens from patients with interstitial lung disease identified pulmonary LCH in only 5%.

A confident diagnosis of pulmonary LCH often can be made based on the patient's age, smoking history, and characteristic HRCT scan findings, especially if patients are followed without treatment.

Definitive diagnosis, if necessary, can be made by identification of Langerhans cell granulomas in lung biopsy samples acquired by video-assisted thoracoscopy. Biopsy sites are selected on the basis of HRCT scan findings. [13] Transbronchial biopsy has a low diagnostic yield (10-40%) because of the patchy nature of the disease and the small amounts of tissue obtained.

Treatment consists of smoking cessation, which stabilizes symptoms in most patients. Corticosteroids are used in progressive or systemic disease. Cytotoxic agents (eg, cyclophosphamide) can be employed for patients who do not respond to smoking cessation and steroids. No treatment has been confirmed to be useful, and no double-blind therapeutic trials have been reported. Lung transplantation also has been performed for treatment of LCH.

Standard-of-care chemotherapy (vinblastine, prednisone, and mercaptopurine) fails to cure more than 50% of children with high-risk disease (ie, children with liver, spleen, or bone marrow involvement). [9]

The annual incidence of LCH has been reported to be 4.6 cases per 1 million children younger than 15 years. The incidence in adults is estimated to be 1 to 2 cases per million. Isolated bone lesions typically present in patients between the ages of 5 and 15 years, but multisystem LCH tends to present in patients younger than 5 years. Children with liver, spleen, or bone marrow involvement are at highest risk for death from LCH. [5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12]

Radiography

Chest radiographs are normal in fewer than 10% of patients. Usually, diffuse reticulonodularity (3- to 10-mm nodules that may cavitate) is observed in a symmetrical pattern, predominantly in the upper and middle lobes (bases tend to be spared). [23]

Lung volumes are generally preserved, or even increased, in contrast to most other pulmonary infiltrative diseases. [13] Associated pneumothorax is found in 15-25% of patients, and pleural effusion is rare.

In the late stage, diffuse cysts may be found that spare only the costophrenic angles.

Computed Tomography

On chest HRCT scans, the distribution of the disease is similar to that seen on chest radiography, with an upper lobe predominance (see the images below). [3, 16, 17] Findings include the following:

-

Centrilobular opacities

-

Small nodules (1-5 mm, may be up to 1.5 cm)

-

Cystic cavitation of small nodules; this is not readily visible on plain radiographs [13]

-

Cysts (initially thick walled, typically progressing to thin walled over time)

Chest CT in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma demonstrates scattered cavitary and noncavitary nodules.

Chest CT in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma demonstrates scattered cavitary and noncavitary nodules.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows the typical combination of nodules, cavitated nodules, and thick- and thin-walled cysts. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows the typical combination of nodules, cavitated nodules, and thick- and thin-walled cysts. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with advanced pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows numerous pulmonary cysts of various sizes, which are confluent in some places. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with advanced pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows numerous pulmonary cysts of various sizes, which are confluent in some places. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

Some authors believe that nodules do not cavitate and cysts represent a paracicatricial emphysematous change adjacent to nodules. Cysts usually are smaller than 10 mm, although cysts larger than 10 mm are found in more than 50% of patients. Cyst walls usually are thin (< 1 mm) but can vary, and the cysts are not necessarily round; they may be bilobed or branching. The intervening lung parenchyma appears normal. The extent of cystic involvement seen on HRCT scans has been correlated with the degree of lung function impairment. [24]

In the early stages, only nodules may be seen. In the late stages, diffuse cysts may be seen, with no nodules evident (approximately 20% of patients). Late-stage disease may be indistinguishable from lymphangiomyomatosis; however, sparing of the costophrenic angles suggests the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma. Mediastinal adenopathy has been described in some series but usually is uncommon. Other authors report mediastinal adenopathy in as many as 30% of patients. [25, 26]

A diagnosis of pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma can be established with a high degree of confidence when small nodules and cysts are seen in a young adult patient with a history of smoking. [27, 28]

On CT scans of 40 patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis, 25 patients were found to have cysts involving upper lung zones with costophrenic sparing, 9 had a micronodular pattern in the middle-upper zone, and 6 had a combination of the 2 radiologic patterns. Pulmonary hypertension was seen in 4 patients. [15]

Nuclear Imaging

Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-CT (FDG-PET-CT) is becoming the preferred imaging modality for diagnosis and assessment of response to therapy in LCH with bone involvement. [1, 19, 20]

A retrospective review by Ferrell et al of patients with histopathology-confirmed LCH at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center determined that FDG PET/CT is vital in the evaluation of LCH lesions because it can detect LCH lesions that are not detectable on conventional imaging and can distinguish between metabolically active and metabolically inactive disease. Of the 107 PET/CT images, in 13 images, increased uptake was observed on PET in an area with no identifiable lesion on conventional imaging. On 8 skeletal surveys, 3 other radiographs, 4 diagnostic CTs, 5 localization CTs, and 1 bone scan, no lesion was identified in an area with increased FDG uptake. [21]

In a retrospective review, by Jessop et al, of 109 FDG PET/CT scans in 33 patients (age range, 7 wk to 18 yr), FDG PET/CT was found to be highly sensitive for the staging and follow-up of pediatric patients with LCH, as well as having a very low false-positive rate. This is important because accurate staging is essential for selecting the most appropriate therapy, which can range from from local surgery to chemotherapy. Of the 33 patients, 19 had single-system, bone unifocal disease; 7 had single-system, bone multifocal disease; 4 had single-system, skin unifocal disease; 2 had multisystem disease; and 1 had single-system, lymph node disease. At staging, FDG PET/CT detected all sites of biopsy-proven LCH (except where bone unifocal disease had been resected). The per-patient false-positive rate of FDG PET/CT at staging was 4% (1/26). During follow-up, 5 LCH recurrences and 1 case of progressive disease on therapy occurred, all of which were positive on FDG PET/CT. The per-scan false-positive rate of FDG PET/CT during follow-up was 2% (2/83). [22]

-

Chest CT in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma demonstrates scattered cavitary and noncavitary nodules.

-

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows the typical combination of nodules, cavitated nodules, and thick- and thin-walled cysts. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.

-

High-resolution chest CT scan in a patient with advanced pulmonary eosinophilic granuloma shows numerous pulmonary cysts of various sizes, which are confluent in some places. Image courtesy of European Respiratory Society Journals LTD.