Practice Essentials

Eosinophilic granuloma (EG) is a rare, benign tumorlike disorder characterized by clonal proliferation of antigen-presenting mononuclear cells of dendritic origin known as Langerhans cells. It is the most common variant of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). The other two variants of LCH—Letterer-Siwe disease and Hand-Schuller-Christian disease—are multisystem syndromes, with manifestations ranging from isolated bone lesions to multisystem disease. [1] Any organ or system of the human body can be affected, but 80% of cases are skeletal and account for less than 1% of all bone tumors. [1] Children between 1 and 15 years of age make up more than 50% of cases of LCH, with peak incidence in children younger than 3 years. [2]

Eosinophilic granuloma is characterized by single or multiple skeletal lesions, but solitary lesions are more common than multiple ones. When multiple lesions occur, the new osseous lesions appear within 1-2 years, and the condition is still classified as EG. Any bone can be involved; the more common sites include the skull, mandible, spine, ribs, and long bones (see the images below). [3, 4, 5] Pathologic fractures may ensue. [3, 6, 7]

Lesions in the long bones are located primarily in the diaphysis. Eosinophilic granuloma frequently involves soft tissues adjacent to bone. In children, the most commonly involved bone is the skull (frontal bone); in adults, the jaw is more frequently involved. The thoracic spine is most often involved in children, as opposed to the cervical spine in adults. The presentation of EG may be solitary, which rarely requires treatment, or multisystem, which requires aggressive therapy. [8]

The diagnosis must be confirmed histopathologically. In addition to pathologic Langerhans cells, inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, eosinophils, and macrophages are observed in microscopy. Immunohistochemically, CD1a, S-100, and Langerin positivity are observed in biopsy and/or surgical excision material. Treatment options may vary depending on localization and extent of the disease. In unifocal EG, close observation of the patient may be preferred, as well as surgical excision, radiotherapy, and intralesional steroid administration. [9] Surgical resection has been the standard treatment for EG, but growing evidence favors watchful waiting, as unifocal calvarial lesions appear to frequently undergo spontaneous remission. [10]

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 30-year-old woman who presented with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region. The radiograph shows an interstitial lung pattern with a honeycomb appearance in the upper zones (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 30-year-old woman who presented with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region. The radiograph shows an interstitial lung pattern with a honeycomb appearance in the upper zones (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Lateral skull radiograph in a 30-year-old woman with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region shows 2 purely lytic lesions in the frontoparietal region of the skull. The larger parietal lesion has beveled edges, suggestive of an eosinophilic granuloma. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Lateral skull radiograph in a 30-year-old woman with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region shows 2 purely lytic lesions in the frontoparietal region of the skull. The larger parietal lesion has beveled edges, suggestive of an eosinophilic granuloma. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

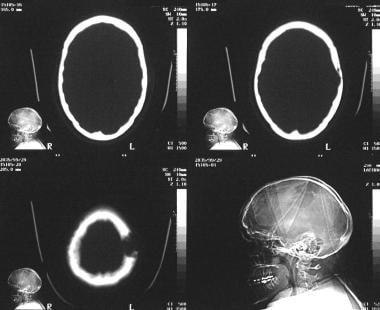

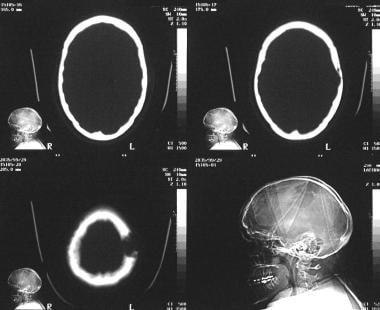

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans of the skull in a 28-year-old woman who presented with a palpable swelling over the calvarium. Scanogram of the patient's skull shows a geographic lytic lesion within the parieto-occipital region. Transaxial scan through the vertex, examined in a bone window, shows an expanding lytic lesion within the diploic space (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans of the skull in a 28-year-old woman who presented with a palpable swelling over the calvarium. Scanogram of the patient's skull shows a geographic lytic lesion within the parieto-occipital region. Transaxial scan through the vertex, examined in a bone window, shows an expanding lytic lesion within the diploic space (see the next image).

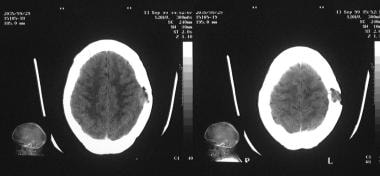

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans through the vertex in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium, examined in a brain window. Images show destruction of both the outer and inner tables of skull; however, no brain involvement is noted.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans through the vertex in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium, examined in a brain window. Images show destruction of both the outer and inner tables of skull; however, no brain involvement is noted.

Because patients with EG may present with multiple bone lesions at a single site (single-system multifocal bone), differentiation must be made from other variants of LCH with bone lesions affecting other organ systems (multisystem, including bone). [2] Radiologists need to be aware that additional eosinophilic granuloma of bone, occurring as long as 4 years after initial diagnosis, should be interpreted as a localized form of LCH. This differentiation is important because decreased mortality has been found in high-risk multisystem LCH patients who had bone involvement, suggesting that those with bone LCH may have more indolent disease. [11]

Lung involvement occurs in 20% of patients with EG who are in an older group (age 20-40 years), with a strong association with smoking. Diffuse pulmonary infiltrates may be a manifestation of a covert osseous disease. In 50-75% of patients, the disease is monostotic. Skull involvement is seen in 50%. [12] Rarely, the growing epiphysis is involved with eosinophilic granuloma; in most such cases, transphyseal extension can be demonstrated, both by radiologic findings and by histopathologic results. [13]

The prognosis for pulmonary EG varies and is related to smoking cessation. Those who continue to smoke experience disease progression, but for those who quit, disease stabilizes or regresses. Extreme age, large cysts, honeycombing radiologic multiorgan involvement, and prolonged corticosteroid therapy lead to a worse prognosis. [8]

Eosinophilic granuloma may masquerade as an aggressive periodontitis [14] ; therefore, EG should be considered when an expanding lytic jaw lesion is encountered.

In a study by Prasad et al, 62 cases of EG with cervical spine involvement were identified in the literature. Mean age at presentation was 32.8 years (range, 18-71 yr), and neck pain, limb weakness, and restriction of movement were the most frequent symptoms. The vertebral body was involved in more than 80% of patients, and only 2 patients had vertebra plana morphology. The most frequently involved vertebra was C2. In 42 patients (82%), only 1 vertebra was affected; there was multiple vertebral involvement in 9 patients (18%). Lytic destruction of the vertebra was the most notable radiologic feature. [15]

Imaging modalities

Eosinophilic granuloma is difficult to diagnose clinically and radiographically because it mimics other odontogenic cysts and tumors. [16] A skeletal survey, a skull series (or low-dose whole bone computed tomography [CT]), and chest radiography (anteroposterior [AP] and lateral) are the first radiographic examinations to be done. Computed tomography of specific areas of the skeleton is indicated when mastoid, orbital, scapular, vertebral, or pelvic lesions are found on plain radiography. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may detect additional osseous or extraosseous lesions. A skeletal scintigram (bone scan) alone does not suffice. [17, 18, 19, 20]

Computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and MRI should be done in cases involving skull, mandible, and spine. Posterior elements of vertebral bodies are difficult to visualize by radiography because of complex anatomy, which requires a spine CT scan. This scan may show punched-out lesions along with any soft tissue involvement adjacent to the bony structure. Radionuclide bone scan shows increased uptake in the region of the lesion. [8]

A wide variety of bone lesions may mimic eosinophilic granuloma; these include infections, traumatic lesions, and neoplasms. A false-negative diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma is exceptional when plain radiographic findings are used, although difficulty may be encountered with lesions in areas with more complex anatomy, such as posterior elements of vertebral bodies. In these cases, conventional tomography or CT may be useful. With radionuclide scanning, the false-negative rate is 30%.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma includes aneurysmal bone cyst, bone infarct and bone metastases, thoracic eosinophilic granuloma, and fibrous dysplasia, as well as acute pyogenic, chronic, and variant osteosarcoma.

When the skull is involved, the following conditions should be considered: venous lake; meningocele, encephalocele, and cranium bifidum; arachnoid granulation; parietal foramen; epidermoid cyst; hemangioma; cholesteatoma; fibrous dysplasia; metastasis; surgical defect; and osteomyelitis.

The presence of vertebra plana should prompt consideration of causes such as fracture, hemangioma, osteomyelitis, metastasis, lymphoma, leukemia, plasmacytoma, chordoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, and Ewing sarcoma. Although EG is the most common cause of vertebra plana, it is distinguished by isolated spinal disease, lack of constitutional symptoms, and minimal laboratory abnormalities. Cervical spine EG manifests more often with osteolytic lesions than with vertebra plana. [1]

When the long bones are affected, Ewing sarcoma, chronic osteomyelitis, Brodie abscess, and chondroblastoma should be considered.

Other interstitial lung diseases should be taken into consideration with pulmonary involvement.

Radiography

Plain radiography remains the mainstay of diagnosis in patients with EG, although a specific diagnosis cannot always be made without bone biopsy, because children and adolescents are not spared skeletal neoplasms. In descending order of frequency, sites involved with monostotic osseous disease include calvarium, mandible, ribs, long bones of the upper extremity, pelvis, and vertebrae (see the images below). [21]

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 30-year-old woman who presented with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region. The radiograph shows an interstitial lung pattern with a honeycomb appearance in the upper zones (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 30-year-old woman who presented with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region. The radiograph shows an interstitial lung pattern with a honeycomb appearance in the upper zones (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Lateral skull radiograph in a 30-year-old woman with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region shows 2 purely lytic lesions in the frontoparietal region of the skull. The larger parietal lesion has beveled edges, suggestive of an eosinophilic granuloma. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Lateral skull radiograph in a 30-year-old woman with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region shows 2 purely lytic lesions in the frontoparietal region of the skull. The larger parietal lesion has beveled edges, suggestive of an eosinophilic granuloma. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

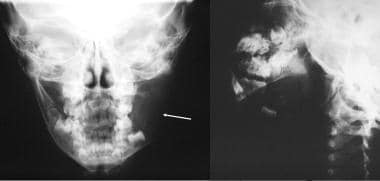

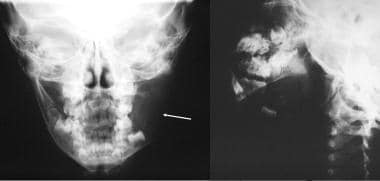

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the mandible (left image) in a 10-year-old boy who presented with swelling of the left mandible. A lytic expanding lesion is seen within the ramus of the left mandible. An oblique view of the mandible (right image) shows floating teeth within the lytic bone lesion (see the angiogram).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the mandible (left image) in a 10-year-old boy who presented with swelling of the left mandible. A lytic expanding lesion is seen within the ramus of the left mandible. An oblique view of the mandible (right image) shows floating teeth within the lytic bone lesion (see the angiogram).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 10-year-old girl shows a lytic lesion of eosinophilic granuloma within the left ileum. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 10-year-old girl shows a lytic lesion of eosinophilic granuloma within the left ileum. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 9-year-old boy who presented with mid dorsal pain. Note the collapsed vertebra and paraspinal soft-tissue mass.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 9-year-old boy who presented with mid dorsal pain. Note the collapsed vertebra and paraspinal soft-tissue mass.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the dorsal spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain. These results confirm the chest radiographic findings.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the dorsal spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain. These results confirm the chest radiographic findings.

When tubular bones are involved in EG, diaphyseal and metaphyseal localization is more frequent than epiphyseal localization. Epiphyseal lesions may cross the open physeal plate.

The skull is affected in one half of patients, [5, 12] including the diploic space of parietal and temporal bones. Skull lesions are lytic, with a beveled edge or sharp and serrated margins and absence of sclerosis in calvarial lesions. A hole-within-a-hole appearance may occur as a result of uneven erosion of the inner and outer tables of the skull. In addition, sclerosis may occur around orbital lesions, as well as marginal sclerosis during the healing phase, in up to 50% of patients with a calvarial lesion. A button sequestrum is seen because a central bone opacity within a lytic lesion is an unusual presentation.

A soft tissue mass overlying the skull defect may be obvious; this mass is often clinically palpable. A soft tissue mass also may be seen occasionally with orbital lesions, with or without underlying bone erosion.

Mandibular lesions may be associated with gingival and soft tissue swelling and floating teeth (see the image below).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the mandible (left image) in a 10-year-old boy who presented with swelling of the left mandible. A lytic expanding lesion is seen within the ramus of the left mandible. An oblique view of the mandible (right image) shows floating teeth within the lytic bone lesion (see the angiogram).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the mandible (left image) in a 10-year-old boy who presented with swelling of the left mandible. A lytic expanding lesion is seen within the ramus of the left mandible. An oblique view of the mandible (right image) shows floating teeth within the lytic bone lesion (see the angiogram).

The ribs show lytic expansile lesions, which may be associated with pathologic fractures. The scapulae and the pelvis show destructive lesions; periosteal elevation is minimal, and some lesions show sclerotic margins, particularly lesions occurring in supra-acetabular regions.

Long bones below the knees and distal to the elbows are rarely involved. Lesions are lytic, round or oval, and expansile, with ill-defined or sclerotic margins. The medullary cavity may be expanded, which may be associated with cortical thinning, intracortical tunneling, and erosion of the cortex, as well as an adjacent soft tissue mass. Laminated periosteal new bone formation is common around the involved segment of bone, but spread across growth plates is unusual. Tubular long bone lesions may appear rapidly over 3 weeks.

Vertebral destruction may lead to flattening of the vertebral body, which is termed vertebra plana—a finding that is much more common in children than in adults and is more common in the dorsal spine. [22, 23, 24] An associated paraspinal mass occasionally may occur. Associated kyphosis has not been described, but scoliosis can occur. Eosinophilic granuloma can produce expansile lytic lesions of vertebral bodies and posterior vertebral elements. However, involvement of the second cervical vertebra is extremely rare and may cause atlantoaxial instability. [25]

Lung involvement is seen in as many as 20% of patients in an older subset (ie, age 20-40 years), with an incidence of 0.05 to 0.50 per 100,000 patients annually. Plain radiographic findings may demonstrate an alveolar pattern at an early stage, which may be followed by nodular shadows (3-10 mm) and/or a reticulonodular pattern with a predilection for the apices. Eventually, fibrosis and a honeycomb lung may ensue. Recurrent pneumothoraces occur in 20% of patients. Hilar lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions are rare.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is considerably better than plain radiography and conventional tomography in depicting an intracranial extension of eosinophilic granuloma. Computed tomography scans may be particularly useful for osseous lesions in areas with complex anatomy such as mastoids, atlantoaxial joints, and posterior elements of vertebral bodies. Also, soft tissue components are better depicted with CT scanning than with other imaging modalities. Destruction of the mastoid, petrous ridge, tegmen tympani, and lateral sinus plate and destruction of the inner and external ear are depicted elegantly on CT scans (see the images below). Computed tomography may reveal an isoattenuating and homogeneously enhancing mass in the hypothalamus/pituitary gland. [18] Appearances of eosinophilic granuloma on CT are nonspecific, and a variety of inflammatory and neoplastic processes may mimic this condition.

Computed tomography of long bones with LCH indicate thick diaphysis and thin cortical bone. Round or ovoid radiolucent areas suggest osteolytic, cystic, or expansile bone destruction. Cross-sectional CT scans show lytic and periosteal reactions, medullary bone destruction, and cortical bone destruction. [2]

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans of the skull in a 28-year-old woman who presented with a palpable swelling over the calvarium. Scanogram of the patient's skull shows a geographic lytic lesion within the parieto-occipital region. Transaxial scan through the vertex, examined in a bone window, shows an expanding lytic lesion within the diploic space (see the next image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans of the skull in a 28-year-old woman who presented with a palpable swelling over the calvarium. Scanogram of the patient's skull shows a geographic lytic lesion within the parieto-occipital region. Transaxial scan through the vertex, examined in a bone window, shows an expanding lytic lesion within the diploic space (see the next image).

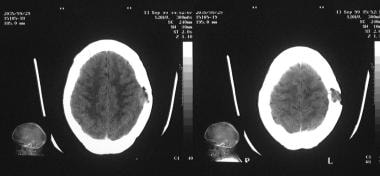

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans through the vertex in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium, examined in a brain window. Images show destruction of both the outer and inner tables of skull; however, no brain involvement is noted.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans through the vertex in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium, examined in a brain window. Images show destruction of both the outer and inner tables of skull; however, no brain involvement is noted.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The value of using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for patients with EG lies in the sensitivity of this modality; its specificity is low. However, the cost of the procedure and procedural problems encountered in conducting imaging in young children confer no advantages over plain radiography.

The soft tissue component around the osseous lesion has poor definition and shows signal inhomogeneity; this appearance may mimic that of malignant tumor, infection, or stress fracture. On spin-echo MRI, osseous lesions of EG reveal decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences. The lesion may enhance after administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent (see the following image). [17]

Eosinophilic granuloma. T1-weighted nonenhanced sagittal magnetic resonance image through the spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain shows the vertebra plana. Note the preserved disk spaces. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. T1-weighted nonenhanced sagittal magnetic resonance image through the spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain shows the vertebra plana. Note the preserved disk spaces. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). This disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after they were given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Ultrasonography

Conventional radiography, CT, and radionuclide imaging usually can successfully diagnose these lesions. Ultrasound of the skull with guided core biopsy has been reported in 3 cases with excellent results. [26] Viewing of the frontal bone solitary EG with ultrasound has been found to be instructive and useful.

(See the images below.)

Eosinophilic granuloma. T1-weighted nonenhanced sagittal magnetic resonance image through the spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain shows the vertebra plana. Note the preserved disk spaces. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. T1-weighted nonenhanced sagittal magnetic resonance image through the spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain shows the vertebra plana. Note the preserved disk spaces. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. CT image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

Eosinophilic granuloma. CT image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

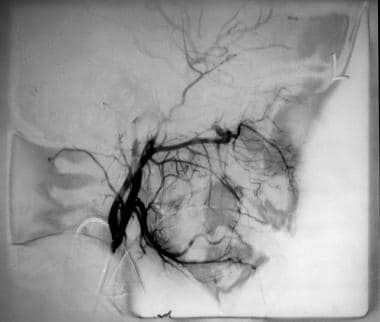

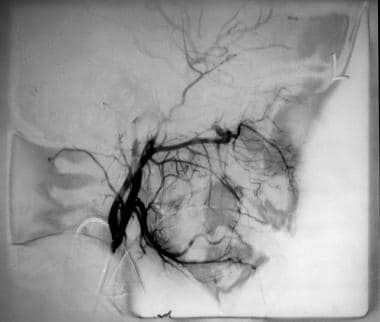

Compare the vascularity of an EG in the first image below, where only stretching of the vessels is noted on angiography. Doppler interrogation in the second image shows internal vascularity not previously evident.

Eosinophilic granuloma. External carotid angiogram in a 10-year-old boy with swelling of the left mandible shows an avascular mass within the mandible, with stretching of the vessels around the lytic lesion. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. External carotid angiogram in a 10-year-old boy with swelling of the left mandible shows an avascular mass within the mandible, with stretching of the vessels around the lytic lesion. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Nuclear Imaging

Radiographic examination and radionuclide bone imaging are complementary techniques for detecting bone lesions in bone marrow disorders, including EG. Scintigraphy is more useful in cases of unifocal EG than in cases of multifocal disease, in which radiography is superior. Negative radionuclide findings occur in 35% of patients with known EG in whom plain radiographic findings are positive.

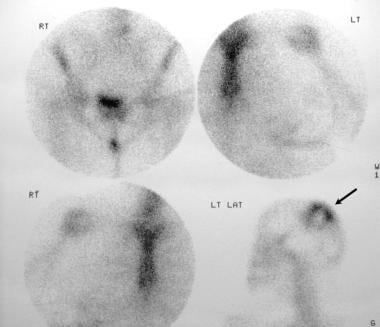

Eosinophilic granuloma shows a variety of activity patterns on radionuclide bone scintigrams obtained by using technetium-99m (99mTc) diphosphonate. The bone lesions may be hot, cold, or cold with an area of increased surrounding reparative-ring activity. Areas of increased activity vary in intensity. In the lower limbs, EG lesions tend to appear more elongated and diffuse than bone metastasis. Recurrences are identified more readily with fewer false-negative findings (see the image below).

Eosinophilic granuloma. Radionuclide bone scans in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium show a solitary lesion within the skull and a photon-deficient mass surrounded by a rim of intense activity. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. Radionuclide bone scans in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium show a solitary lesion within the skull and a photon-deficient mass surrounded by a rim of intense activity. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Bone lesions in all types of Langerhans cell histiocytosis are not gallium-67 (67Ga) citrate–avid, but 67Ga imaging may be helpful for detection of nonosseous lesions. Hence, it is useful for initial assessment and in serial follow-up imaging of patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Thallous chloride-201 (201Tl) uptake detected on single-photon emission CT (SPECT) scans has been reported in a patient with skull EG that was photon deficient on a 99mTc methylene diphosphonate uptake study. [27]

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is more sensitive than gallium scanning and may be used for evaluating patients for LCH. [28] FDG-PET has poor sensitivity for spinal lesions but can be used to identify LCH in tissues, including lymph nodes, spleen, and lung. Obert and colleagues demonstrated that serial FDG-PET-CT scans may be useful for evaluating treatment responses, particularly in patients with bone LCH involvement. [29]

Angiography

In most instances, angiography has little or no role in the investigation of EG. Eosinophilic granuloma shows no neovascularity; therefore, angiography usually is not performed. Rarely, angiography may be performed in patients for whom staging is required before surgical intervention. It can also be used to exclude other vascular lesions that can mimic EG, such as hemangioma and aneurysmal bone cyst (see the following image).

Eosinophilic granuloma. External carotid angiogram in a 10-year-old boy with swelling of the left mandible shows an avascular mass within the mandible, with stretching of the vessels around the lytic lesion. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

Eosinophilic granuloma. External carotid angiogram in a 10-year-old boy with swelling of the left mandible shows an avascular mass within the mandible, with stretching of the vessels around the lytic lesion. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 30-year-old woman who presented with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region. The radiograph shows an interstitial lung pattern with a honeycomb appearance in the upper zones (see the next image).

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Lateral skull radiograph in a 30-year-old woman with shortness of breath and a palpable swelling over the right parietal region shows 2 purely lytic lesions in the frontoparietal region of the skull. The larger parietal lesion has beveled edges, suggestive of an eosinophilic granuloma. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans of the skull in a 28-year-old woman who presented with a palpable swelling over the calvarium. Scanogram of the patient's skull shows a geographic lytic lesion within the parieto-occipital region. Transaxial scan through the vertex, examined in a bone window, shows an expanding lytic lesion within the diploic space (see the next image).

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Transaxial nonenhanced computed tomography scans through the vertex in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium, examined in a brain window. Images show destruction of both the outer and inner tables of skull; however, no brain involvement is noted.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Radionuclide bone scans in a 28-year-old woman with a palpable swelling over the calvarium show a solitary lesion within the skull and a photon-deficient mass surrounded by a rim of intense activity. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the mandible (left image) in a 10-year-old boy who presented with swelling of the left mandible. A lytic expanding lesion is seen within the ramus of the left mandible. An oblique view of the mandible (right image) shows floating teeth within the lytic bone lesion (see the angiogram).

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. External carotid angiogram in a 10-year-old boy with swelling of the left mandible shows an avascular mass within the mandible, with stretching of the vessels around the lytic lesion. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Plain radiograph of the pelvis in a 10-year-old girl shows a lytic lesion of eosinophilic granuloma within the left ileum. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Chest radiograph in a 9-year-old boy who presented with mid dorsal pain. Note the collapsed vertebra and paraspinal soft-tissue mass.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Anteroposterior radiograph of the dorsal spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain. These results confirm the chest radiographic findings.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. T1-weighted nonenhanced sagittal magnetic resonance image through the spine in a 9-year-old boy with mid dorsal pain shows the vertebra plana. Note the preserved disk spaces. Biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of eosinophilic granuloma.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. CT image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. CT image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. CT image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Ultrasound image of a 4-year-old boy with long-standing (1 yr) gradually increasing swelling over the forehead (left to the midline). Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.

-

Eosinophilic granuloma. Eosinophilic granuloma. Courtesy of Ravi Devidas Kadasne, MBBS, MD, Specialist in Radiology, Emirates International Hospital, UAE.