Practice Essentials

Endometrial cancer is the most common female genital cancer, with the most common type being adenocarcinoma. Carcinoma of the endometrium may develop in normal, atrophic, or hyperplastic endometrium. Most endometrial cancers are detected at an early stage, with the tumor confined to the uterine corpus in 75% of patients. The prognosis generally is favorable. [1, 2, 3, 4] Multiple risk factors associated with endometrial cancer include conditions associated with disorders of menstruation, increased perimenopausal bleeding, menopause after age 52 years, long time period between menarche and menopause, estrogen replacement therapy, tamoxifen therapy for breast cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, obesity, nulliparity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. Genetic predisposition appears to play a role, since risk factors also include a family history of endometrial or breast cancer and a personal history of ovarian or breast cancer. [5, 6]

Approximately 75% of women with endometrial cancer are postmenopausal. Thus, the most common symptom is postmenopausal bleeding. For the 25% of endometrial cancers in patients who are perimenopausal or premenopausal, the symptoms suggestive of cancer may be subtler. [5, 6]

(Images of endometrial carcinoma are provided below.)

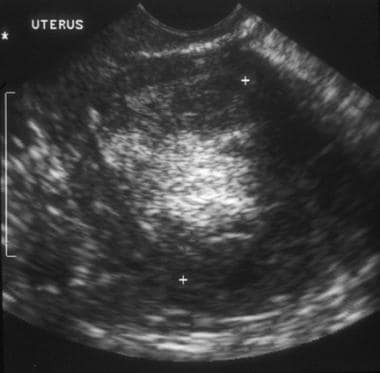

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. Sagittal transvaginal ultrasound image of the uterus shows a central mass replacing the endometrial stripe, with hyperechoic and hypoechoic regions.

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. Sagittal transvaginal ultrasound image of the uterus shows a central mass replacing the endometrial stripe, with hyperechoic and hypoechoic regions.

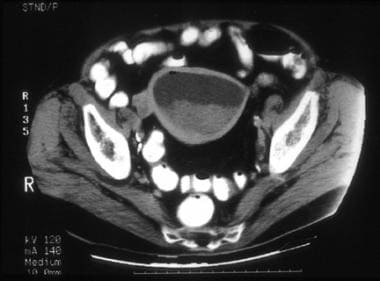

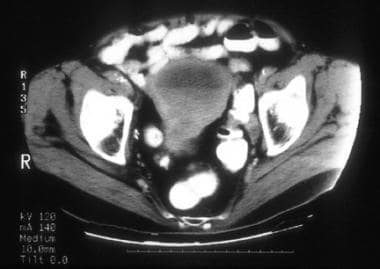

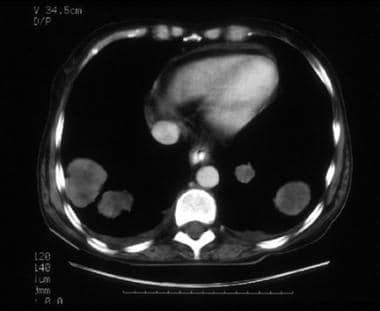

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4.0 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4.0 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

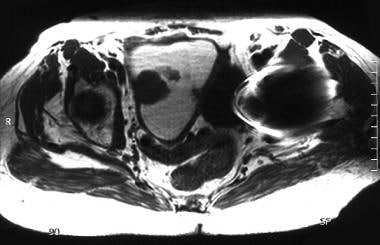

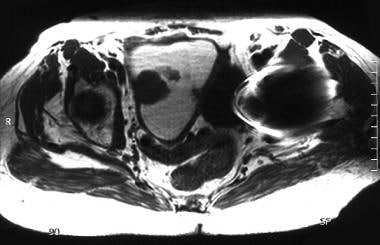

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Axial T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the right side of the endometrium and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Axial T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the right side of the endometrium and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

Preferred examination

Endometrial biopsy, usually using an aspiration-type curet or other device, is generally accepted as the first-step office procedure for the diagnosis of endometrial cancer and should be coupled with endocervical curettage. The procedure is definitive if results are positive for malignancy. The reported accuracy of the procedure is approximately 90%.

Ultrasonography is the modality of choice for the initial imaging evaluation of female pelvic organs. [7] US is widely available in many regions of the world, is relatively inexpensive, is noninvasive, and does not use ionizing radiation. Typical examinations include transabdominal ultrasonography (TAUS) and transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS), which are supplemented by color Doppler imaging as needed. [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 2, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

TAS is performed through subcutaneous fat and abdominal wall muscles and uses the full urinary bladder as an acoustic window. TAS transducers, needed in most patients to penetrate the abdominal wall and adequately visualize pelvic organs, have lower frequency and resolution than TVS probes.

TVS has the advantage of using high-frequency transducers that are placed close to the regions of interest and produce high-resolution images of significantly better quality than transabdominal images. While both TAS and TVS allow visualization of the endometrium, exquisitely finer endometrial details are possible to depict transvaginally rather than transabdominally. [18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]

TVS is clinically established as the preferred technique for evaluation of endometrial disorders and is especially useful in the workup of abnormal uterine bleeding. Hysterosonography can be used to identify the cause of endometrial stripe thickening in some patients. [24, 25, 13, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30] The procedure consists of TVS performed with sterile fluid placed within the endometrial cavity and may help show a thick endometrial stripe as secondary to diffuse or focal endometrial thickening, endometrial polyp, submucosal leiomyoma, or synechiae. This may help further diagnostic planning.

TVS is superior to CT and approaches MRI in its ability to depict endometrial carcinoma and to provide information regarding myometrial, cervical, and, perhaps, parametrial tumor invasion. However, US is unable to depict the entire intrapelvic or intra-abdominal anatomic regions adequately; therefore, US is not suitable for the comprehensive staging of endometrial carcinoma. US has significantly lower sensitivity than CT in detecting enlarged abdominal or pelvic lymph nodes and in depicting intraperitoneal, omental, or mesenteric metastases. In addition, US is inferior to CT in assessing pelvic sidewall extension and adjacent organ invasion.

CT and MRI are more accurate staging modalities than US. [31] Both techniques allow survey of the entire pelvis, abdomen, thorax, and brain. CT is available more widely, is less costly than MRI, provides rapid image acquisition, and has high spatial resolution. The advantages of CT also include the availability of GI and intravenous (IV) contrast materials. Opacification of the GI tract with oral and rectal contrast facilitates optimal evaluation of the bowel and helps distinguish intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal masses from bowel. IV contrast injection improves evaluation of vascular structures and detection of mass lesions in parenchymatous organs. Spiral/helical and multidetector technology has improved the multiplanar capability of CT. [32, 33, 34]

The advantages of MRI include superior spatial and tissue contrast resolution, multiplanar capabilities, lack of exposure to ionizing radiation, and availability of noniodinated, nonnephrotoxic IV contrast material. [35]

Kaneda et al found that use of 3.0T MRI to determine the depth of myometrial invasion was equivalent to use of 1.5T MRI in a cohort of 50 women with histopathologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma. [36]

Alcazar and Galvan evaluated the role of 3-dimensional power Doppler angiography (3D-PDA) to discriminate between benign and malignant endometrial disease in women with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrium, and they found that endometrial volume, vascularity index (VI), and vascularity-flow index were significantly higher in malignant conditions. Receiver operating characteristic analysis revealed that VI was the best parameter for the prediction of endometrial cancer. Histologic diagnoses were endometrial cancer (44 cases), hyperplasia (13 cases), polyp (23 cases), cystic atrophy (14 cases), and submucous myoma (5 cases). [14]

Signorelli et al performed a retrospective study to determine the diagnostic accuracy of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) in detecting nodal metastases in patients with high-risk endometrial cancer; pelvic node metastases were found at histopathologic analysis in 9 of the 37 patients (24.3%). Patient-based sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were 77.8%, 100.0%, 100.0%, 93.1%, and 94.4%, respectively. Nodal lesion site-based sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy were 66.7%, 99.4%, 90.9%, 97.2%, and 96.8%, respectively. [37]

Khoury-Collado et al described sentinel lymph node (SLN) detection rates in endometrial cancer and estimated how many cases are needed to achieve greater than 90% SLN detection: when examining an individual provider's performance, after the first 30 cases, the rate of successful mapping significantly increased from 78% to 94%. The study included 115 patients with endometrial cancer. In the initial 27 months of the study, an SLN was identified in 50 of 64 cases (78%), with 2 false negatives. In the subsequent 15 months, successful mapping was achieved in 48 of 51 cases (94%), with no false negatives. [38]

Histopathologic features of the tumor and clinical findings at presentation influence the choice of imaging modality for preoperative staging of endometrial cancer. Kinkel et al [39] provided clinical practice guidelines for staging based on a meta-analysis of the usefulness of MRI, CT, and US in imaging patients with endometrial cancer:

-

Patients with grade 1 tumor, a clinically normal-sized uterus, and no clinical evidence of coexisting pelvic disease generally require no preoperative imaging because the risk for myometrial, cervical, or lymph node disease is low. If the clinical evaluation is inconclusive or if coexisting pelvic disease is suggested, then US, CT, or MRI may be used for the initial imaging evaluation.

-

In patients at risk for disease dissemination and lymph node involvement at presentation (because of tumor grade, histologic cell type, or clinical findings), CT or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis should be performed to determine the extent of tumor spread.

-

Patients in whom cervical invasion is suggested clinically or in whom endocervical curettage was inconclusive benefit in particular from MRI, because MRI can depict cervical and myometrial invasion most accurately [40] and is approximately equivalent to CT in detecting enlarged lymph nodes.

MRI, with its exquisite soft tissue contrast and multiplanar capability, is superior to US and CT in helping assess the depth of myometrial invasion, cervical invasion, and early parametrial invasion. [15] MRI is approximately equivalent to CT in detecting enlarged lymph nodes, but CT is considerably superior to MRI in detecting and distinguishing intraperitoneal, omental, and mesenteric metastases from bowel.

Although MRI is superior to CT in evaluating myometrial and cervical invasion and is the best alternative for patients with significant contrast allergies or renal malfunction, CT is more sensitive than MRI in the overall detection of tumor spread outside the uterus. In addition, CT remains the imaging modality used most frequently in clinical practice for comprehensive preoperative evaluation of the extent of disease. [41]

CT is clinically advocated in the evaluation of patients with poorly differentiated or high-grade tumor, serous papillary carcinoma, or clear cell carcinoma because of the high risk for advanced disease and metastatic lymphadenopathy at the time of presentation. CT also is advised for patients who have abnormal liver function test results, elevated serum cancer antigen-125 levels, clinical suggestion of advanced disease, or inconclusive clinical evaluation.

Limitations of techniques

US is operator-dependent; it has relatively poor spatial and tissue contrast resolution compared with MRI and CT; its image quality is degraded by large body habitus; and visualization of portions of the pelvis and abdomen is precluded by bowel gas and bony structures. The transabdominal approach also is influenced by the degree of bladder filling and is impeded by the presence of surgical incision, dressings, drains, or skin lesions. Transvaginal probes have inherent limitations, including small field of view, short range of penetration of high-frequency transducers, and occasional patient intolerance or lack of acceptance of the transvaginal approach.

CT uses ionizing radiation and has inferior soft tissue contrast resolution, making it less capable than MRI for distinguishing between tumor and normal soft tissues in the uterine corpus and cervix. CT image quality is degraded by metallic prostheses, an extremely large body habitus, and patient or respiratory motion. The iodinated IV contrast available for CT is associated with a risk of significant allergic reactions (including fatal anaphylaxis), nephrotoxicity, and complications of contrast extravasation.

CT does not depict the endometrium consistently and is not reliable for accurate evaluation of its thickness. Immediate postcontrast dynamic CT scans of the uterus often show central hypoattenuation that may be related to secretions in the cavity or a lag in contrast enhancement of the endometrium compared to myometrium; however, the endometrium is not visualized distinctly as separate from the myometrium, and accurate measurement of its thickness is not feasible. This is because the endometrium and myometrium have similar attenuation and cannot be distinguished either on CT scans obtained without intravenous contrast or on routine or delayed postcontrast CT scans.

MRI depicts the endometrium as a central zone of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, while the myometrium is depicted at its inner aspect as a zone of low signal intensity (junctional zone) and at its outer aspect as a wider zone of intermediate signal intensity. On T1-weighted images, the endometrium has intermediate signal intensity similar to the myometrium; therefore, the endometrium is not visualized distinctly as separate from the myometrium.

MRI is contraindicated in patients who have vital metallic biomedical devices or metallic objects in strategic anatomic regions. It is more costly and less readily available than CT and requires long image acquisition times. MRI image quality is degraded by artifacts related to respiratory motion and bowel peristalsis, which are likely to occur during the long image acquisition time. No effective GI contrast material is currently available for MRI. Claustrophobia deters some patients from undergoing MRI.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Computed Tomography

CT is the imaging modality used most commonly in clinical practice to determine the extent of spread of endometrial cancer. Oral, rectal, and IV administration of contrast material is necessary for optimal CT evaluation. IV contrast injection is particularly useful to increase the conspicuity of the endometrial tumor and to facilitate the evaluation of myometrial and cervical invasion. [42, 43, 32, 44, 45]

Endometrial carcinoma and a normal myometrium demonstrate approximately similar attenuation on CT images obtained without IV contrast enhancement; therefore, the two cannot be reliably distinguished on noncontrast CT images. Following IV contrast administration, nonuniform contrast enhancement of the tumor may occur but to a much lesser degree than the usually intense and uniform enhancement of the normal myometrium. Thus, the endometrial tumor may become apparent on postcontrast images as a lesion with relatively low attenuation.

In a prospective study of 10 patients reported by Hamlin et al, none of the endometrial cancers were diagnosed unequivocally on precontrast CT images, and 30% of the cancers were not diagnosed on postcontrast images (even retrospectively in both situations). [46] In 24 patients with primary endometrial malignancy reported by Walsh and Goplerud, CT showed normal uterine attenuation findings in 50% of patients and 1- to 5-cm low-attenuation tumor areas in the uterus in the other 50% of patients. [47] Dimensions of the identified tumors were not evaluated accurately because of volume averaging and the uterine position relative to the axial plane of CT imaging.

In a study of 151 patients with endometrial cancer comparing SPECT/CT with lymphoscintigraphy, overall and bilateral SLN detection rate was better with SPECT/CT than with lymphoscintigraphy in patients with stage I/II endometrial cancer. The bilateral pelvic SLN detection for SPECT/CT was 43% (65/151) versus 32% for lymphoscintigraphy (48/151). The overall pelvic SLN detection rate (at least one pelvic SLN detected) was 77% with SPECT/CT (116/151) versus 68% with lymphoscintigraphy (102/151). [34]

CT findings in endometrial cancer include the following:

-

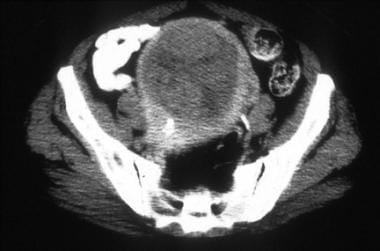

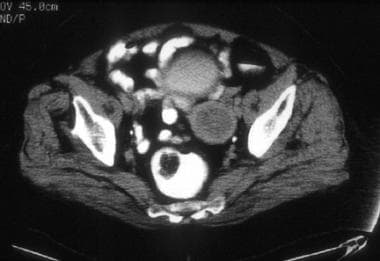

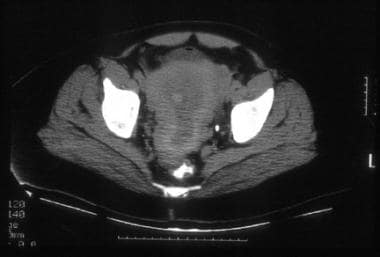

Relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity, as shown in the images below, which may show uniform attenuation or may be heterogeneous, with or without a contrast-enhanced component

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4.0 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4.0 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

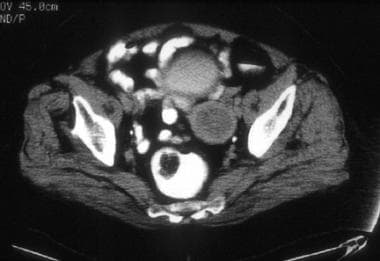

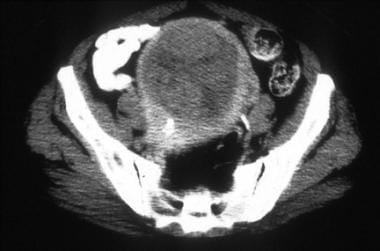

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

-

Polypoid mass surrounded by endometrial fluid

-

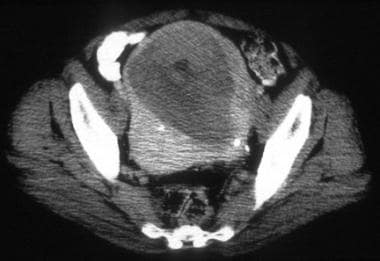

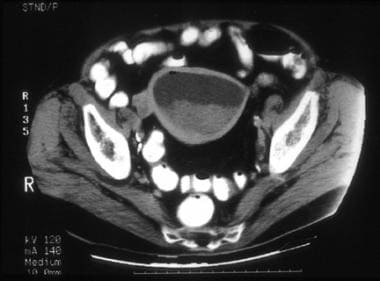

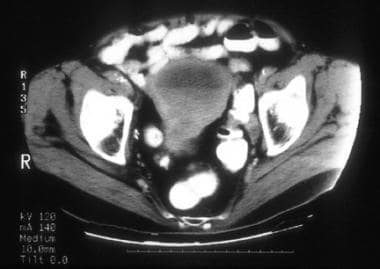

Heterogeneous soft tissue mass/masses and fluid expanding the endometrial cavity, as shown in the images below

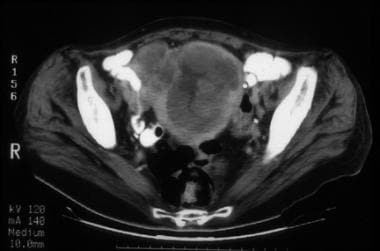

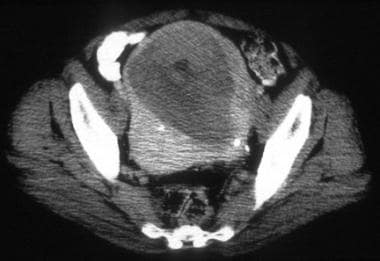

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3. CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3. CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

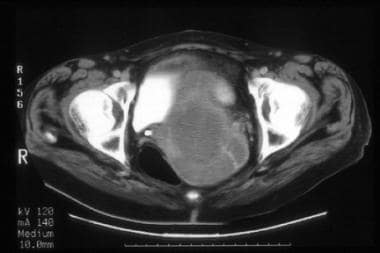

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3 (same patient as above). CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3 (same patient as above). CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

A 64-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with focal squamous differentiation. CT image shows tumor expanding the entire endometrial cavity. The myometrium is markedly thinned and its inner margins are ill defined. Surgical pathology confirmed tumor involvement of the cervix and the outer third of the myometrium.

A 64-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with focal squamous differentiation. CT image shows tumor expanding the entire endometrial cavity. The myometrium is markedly thinned and its inner margins are ill defined. Surgical pathology confirmed tumor involvement of the cervix and the outer third of the myometrium.

-

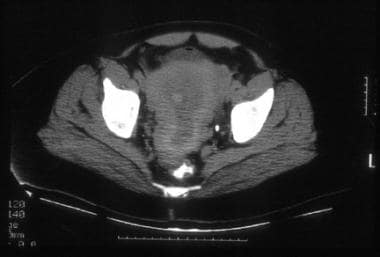

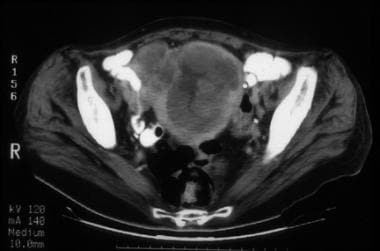

Tumor involving multiple regions of the endometrium or the entire endometrial surface, as shown in the images below:

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type. CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type. CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type (same patient as above). CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type (same patient as above). CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

-

Fluid-filled uterine cavity marginated by mural tumor implants, as shown in the image below:

-

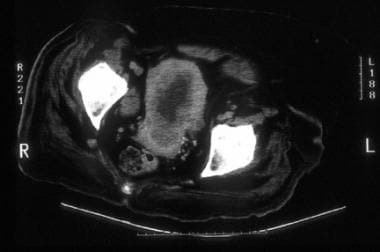

Fluid-filled uterine cavity secondary to obstruction of the endocervical canal by tumor that is not depicted or delineated clearly, as shown in the images below:

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrium in the fundus is thin but well defined. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrium in the fundus is thin but well defined. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (same patient as above). CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrial and endometrial regions in the lower uterus are ill defined and slightly heterogeneous. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (same patient as above). CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrial and endometrial regions in the lower uterus are ill defined and slightly heterogeneous. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

CT staging

The most commonly used staging system for endometrial carcinoma was developed by the Féderation Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO), in collaboration with several international scientific societies and agencies specializing in research and treatment of female malignancies, including the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). [48]

CT staging of endometrial cancer is based on the surgical/pathologic FIGO classification, as shown below:

-

Stage I - Tumor confined to the uterine corpus

-

Stage II - Tumor invades cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus

-

Stage III - Local and/or regional spread of the tumor

-

Stage IV - Tumor invades bladder and/or bowel mucosa and/or distant metastases

In addition, each stage is subcategorized further as follows in the revised FIGO classification:

-

Stage IA: The tumor is limited to the endometrium or invades less than half of the myometrium. The CT appearance of the uterus may be essentially normal (particularly in patients with noninvasive cancer), or the tumor can be depicted as described in CT Findings.

-

Stage IB: Tumor invasion equal to or more than half of the myometrium. Invasion of the myometrium results in eccentric or focal myometrial thinning; the cancer usually appears hypoattenuated relative to the surrounding uniformly contrast-enhanced normal myometrium, and the demarcation between the invasive tumor and the thinned myometrium is ill-defined, as shown in the image below:

A 57-year-old woman with stage IVB poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. CT image through the mid pelvis. The upper uterus shows confluent soft tissue masses and fluid expanding the endometrial cavity, diffuse myometrial thinning consistent with deep myometrial invasion, and parametrial tumor extension through the disrupted myometrium at the right fundal region. The patient had multiple pulmonary metastases, which is indicative of stage IVB disease.

A 57-year-old woman with stage IVB poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. CT image through the mid pelvis. The upper uterus shows confluent soft tissue masses and fluid expanding the endometrial cavity, diffuse myometrial thinning consistent with deep myometrial invasion, and parametrial tumor extension through the disrupted myometrium at the right fundal region. The patient had multiple pulmonary metastases, which is indicative of stage IVB disease.

-

Stage II: Tumor invasion of the fibromuscular stroma of the cervix, without extrauterine spread, is considered stage II in the FIGO classification. Tumor involvement of the cervical stroma typically results in an enlarged cervix, which shows areas of heterogeneous hypoattenuation or is hypoattenuated diffusely, as shown in the image below. Cervical invasion limited to the endocervical glandular region is not usually identifiable on CT and is considered stage I in the FIGO classification.

-

Stage IIIA: Tumor invades the serosa of the corpus uteri and/or adnexae by direct extension or metastasis

-

Stage IIIB: Vaginal spread, by direct extension or metastasis, and/or parametrial involvement. CT features of parametrial invasion include the following (in order of increasing positive predictive value): loss of definition or irregularity of the uterine contours; increased attenuation and prominent linear soft tissue stranding in the parametrial and periureteral fat; confluent soft tissue replacing the periureteral fat; and 3-dimensional parametrial soft tissue mass

-

Stage IIIC: Metastases to pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes.

-

Stage IVA: Tumor invasion spreads into the urinary bladder or bowel mucosa. CT findings include the following: focal obliteration of the perivesical or perirectal fat; eccentric or asymmetric wall thickening, which can be uniform, nodular, or serrated; and intraluminal extension of soft tissue mass.

-

Stage IVB: Distant metastases, as in the image below, including intra-abdominal metastases and/or inguinallymph nodes. Excludes metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes, vagina, pelvic serosa, or adnexa.

Degree of confidence

The reported overall accuracy of CT staging ranges from 84 to 88%. CT scans help confirm stage I or II disease correctly in 83 to 92% of patients and help identify extrauterine tumor extension correctly in 83 to 86% of patients with stage III or IV disease.

CT limitations in staging endometrial carcinoma include the following:

-

Understaging cancers presenting with microscopic tumor spread.

-

Diminished accuracy in evaluating myometrial invasion in elderly women, particularly in the setting of atrophic myometrium and polypoid endometrial tumors.

-

Overlap with the appearances of other malignant uterine masses and leiomyomata.

-

Similarity in the appearances of the irregular uterine contours and adjacent soft tissue stranding produced by parametrial tumor invasion and by parametritis secondary to fractional curettage or endometrial biopsy.

-

Inability to differentiate lymph between node enlargement resulting from benign causes and that resulting from metastases.

CT findings are not specific for endometrial carcinoma and can be simulated by other conditions, including the following:

-

Endometrial extension of cervical cancer.

-

Endometrial polyp.

-

Leiomyomata.

-

Intrauterine fluid collections, including blood and/or necrotic material (eg, from recent biopsy or curettage).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

State-of-the-art MRI requires the use of a high field-strength system with a torso phased-array coil. Administering antiperistaltic agents such as glucagon to patients is advocated. High-resolution sagittal and axial T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences are obtained in all patients and usually depict the uterine zonal anatomy to greatest advantage. [49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58]

Axial T1-weighted spoiled gradient-echo images also are obtained and are helpful to detect enlarged pelvic lymph nodes. Sagittal T1-weighted spoiled gradient-echo sequences (with or without fat suppression) may be performed following IV injection of paramagnetic contrast material if a need exists to improve tumor detection, distinguish tumor from debris in the endometrial cavity, or facilitate the evaluation of myometrial invasion by increasing the contrast between the tumor and the normal myometrium. [20, 21, 22, 59, 60, 61, 62]

MRI reveals variable abnormal endometrial findings in 81-84% of patients with endometrial carcinoma. The endometrium may be thickened focally or diffusely, demonstrated as irregular in thickness and configuration, or widened by polypoid tumor, as shown in the images below. Furthermore, the signal intensity of the tumor has variable patterns on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images. However, the endometrium may appear entirely normal.

In a retrospective study of 33 women with endometrial cancer, diffusion-weighted MRI was assessed for discriminating between metastatic and nonmetastatic pelvic lymph nodes. DWI-related restricted and nonrestricted features had a sensitivity of 80.6%, a specificity of 100%, and an accuracy of 87.5% to discriminate between a metastatic and nonmetastatic pattern. [63] Another study, by Reyes-Perez et al, suggested that the apparent diffusion coefficient on MRI may be a useful indicator to predict malignancy of endometrial cancers. [64]

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Axial T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the right side of the endometrium and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Axial T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the right side of the endometrium and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted image of the uterus, following the administration of gadolinium, shows mild contrast enhancement of polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted image of the uterus, following the administration of gadolinium, shows mild contrast enhancement of polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T2-weighted image of the uterus without gadolinium shows slightly hyperintense polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The tumor size is underestimated secondary to the surrounding isointense fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity; the fluid is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images and is consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T2-weighted image of the uterus without gadolinium shows slightly hyperintense polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The tumor size is underestimated secondary to the surrounding isointense fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity; the fluid is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images and is consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

A review of the findings depicted by unenhanced MRI of 45 patients with endometrial cancer, as reported by Hricak et al, revealed the following [23] :

-

No abnormal endometrial signal in 15.6% of patients, although hysterectomy specimens showed tumors measuring as large as 1-3 cm.

-

No abnormal signal in 31.1% of patients on T1-weighted images, while T2-weighted images depicted the tumor with a uniform signal intensity lower than adjacent normal endometrium.

-

No abnormal signal in 20% of patients on T1-weighted images, while T2-weighted images showed heterogeneous tumor with low and high signal intensities compared to normal endometrium.

-

In 15.6% of patients, endometrial blotches of medium or high signal intensity were noted on T1-weighted images, while on T2-weighted images, the tumor was of uniformly high signal intensity/

-

In 17.8% of patients, tumor was isointense with normal endometrium, and the only abnormal finding was a measurably thickened endometrium.

Thus, unenhanced T1-weighted MRI demonstrated endometrial tumor as follows:

-

Isointense with the remainder of the uterus in 84.4% of patients.

-

Having medium or high signal intensity in 15.6% of patients.

Unenhanced T2-weighted MRI demonstrated endometrial tumor as follows:

-

Isointense with the normal endometrium in 49% of patients.

-

Having uniform signal intensity lower than normal endometrium in 31.1% of patients.

-

Heterogeneous with low and high signal intensity in 20% of patients.

Endometrial tumor was isointense with the surrounding endometrium on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images in 33.4% of patients.

MRI staging

Similar to CT staging, MRI staging of endometrial carcinoma is based on the surgical/pathologic FIGO classification, [48] as follows:

-

Stage IA: The tumor is confined to the endometrium, and the endometrial-myometrial interface is continuous and smooth; when visible, the myometrial junctional zone is preserved and intact.

-

Stage IA: Tumor extending to less than half of the myometrial width is also considered stage IA in the latest FIGO revision and may result in irregularity and indistinctness of the endometrial-myometrial interface, segmented disruption or discontinuity of the myometrial junctional zone when present, and/or high signal intensity of tumor evident in the inner half of the myometrium

-

Stage IB: The tumor extends into half or more of the myometrial width, and the uterine serosal surface is preserved and intact.

-

Stage II: Tumor extending into the fibromuscular stroma of the cervix, without extrauterine spread, is considered stage II in the latest FIGO revision (rather than stage IIB of the old system) and may result in heterogeneous signal intensities in the cervical stroma region with or without enlargement of the cervix. Cervical invasion limited to the endocervical glandular region is considered stage I in the latest FIGO revision (rather than stage IIA of the old system).

-

Stage IIIA: Tumor invading the serosa of the corpus uteri and/or adnexae by direct extension or metastasis. Associated disruption of the uterine serosal surface should be confirmed in 2 planes.

-

Stage IIIB: Vaginal spread, by direct extension or metastasis, and/or parametrial involvement. The vaginal involvement may be evidenced by segmental loss of the hypointense vaginal wall signal. Extrauterine tumor extension into the parametrial region causes distruption of the uterine serosal surface.

-

Stage IIIC: Enlarged pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes characterize this stage

-

Stage IVA: Invasion of the bladder or bowel mucosa is demonstrated, resulting in disruption of the tissue planes between the uterus and bladder or rectum and focal alteration or loss of low signal intensity of the walls of these structures

-

Stage IVB: Distant metastases, including intra-abdominal metastases, and/or inguinal lymph nodes. Excludes metastasis to para-aortic lymph nodes, vagina, pelvic serosa, or adnexa. This stage is manifested by metastatic masses outside the true pelvis and/or enlarged inguinal lymph nodes.

Degree of confidence

MRI reveals variable abnormal endometrial findings only in approximately 81-84% of patients with endometrial carcinoma.

Overall accuracy of MRI staging is reported to be as high as 85-92%. MRI limitations in staging endometrial carcinoma include the following:

-

Understaging cancers presenting with microscopic tumor spread.

-

Difficulty in consistently differentiating endometrial cancer from benign pathologic findings.

-

Diminished accuracy in evaluating myometrial invasion in the setting of polypoid tumor or blood distending the uterine cavity, resulting in the appearance of a thin myometrium.

-

Difficulty in assessing the depth of myometrial invasion in elderly/postmenopausal patients with an ill-defined or nonvisible myometrial junctional zone or in those who have atrophic myometrium.

-

Relatively low accuracy in identifying metastases to lymph nodes, peritoneum, or adnexal structures.

MRI findings of endometrial cancer are not specific and can be simulated by the following:

-

Adenomatous hyperplasia.

-

Polyp(s).

-

Degenerating submucosal leiomyoma.

-

Endometrial secretions.

-

Blood clots.

IV injection of paramagnetic contrast material may result in enhancement of the endometrial tumor and, thus, may improve tumor detection and allow differentiation between the contrast-enhanced tumor and the unenhanced blood clots or fluid in the endometrial cavity.

Ultrasonography

Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVU) is advocated as the imaging modality of choice for screening for endometrial cancer.

The earliest depicted finding is a thickened endometrium that is usually heterogeneous and poorly defined or has irregular contours. Although echogenicity is variable, in most patients the endometrium is either diffusely or partially more echogenic than the myometrium. These findings are nonspecific, as there is considerable overlap in the US appearances and thickness of the endometrium in patients with carcinoma, hyperplasia, or polyp. Histopathologic evaluation is necessary to determine the diagnosis.

The endometrium is typically measured at its maximal thickness on a midline sagittal image of the uterus obtained by transvaginal US. Endometrial thickness, as reported in the literature, is a bilayer measurement combining the AP width of both the anterior and posterior layers of the endometrium, exclusive of possible intracavitary content. The reported normal range for this bilayer endometrial thickness is up to 5 mm in asymptomatic postmenopausal women not receiving hormones and up to 8 mm in asymptomatic postmenopausal women on HRT. Some advocate calling all measurements greater than 5 mm abnormal with or without HRT.

The role of ultrasound in the evaluation of women with postmenopausal bleeding is thoroughly discussed in a consensus statement by the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. [65]

To minimize the risk of missing premalignant or malignant lesions, most experts advocate endometrial sampling when the US endometrial thickness is greater than 8 mm in asymptomatic postmenopausal women or 5 mm or greater in postmenopausal patients having abnormal uterine bleeding, regardless of whether the women are receiving hormones.

Abnormal uterine bleeding in women with endometrial thickness of less than 5 mm has been thought to be almost always associated with endometrial atrophy; therefore, a histologic diagnosis may not be necessary in such patients. Some clinicians still prefer performing endometrial sampling as the initial diagnostic procedure for all symptomatic postmenopausal patients, without attempting to determine the endometrial thickness. Increasing work with hysterosonography reveals a greater number of cases having true causes for the hemorrhage other then "endometrial atrophy."

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of women with postmenospausal bleeding, mean endometrial thickness was found to be substantially higher in women with endometrial cancer than in those without the condition. An endometrial thickness cutoff of ≥5 mm showed an acceptable tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of endometrial cancer, using endometrial volume, vascularization index, vascular flow index, and uterine artery flow index measurements by ultrasonography. [16]

Women on sequential estrogen and progesterone therapy develop cyclic endometrial changes resulting in considerable variation of the endometrial thickness, which is at its maximal dimension on days 13-23 of the cycle. The endometrium in these women should be evaluated at the beginning or at the end of the sequential hormone cycle when the endometrium is likely to be at its thinnest dimension. Women on unopposed estrogen therapy, continuous estrogen and progesterone therapy, or tamoxifen therapy do not undergo as much cyclic endometrial variation, and the timing of the measurement of endometrial thickness is not critical.

Hysterosonography may help in determining further diagnostic planning in some patients, particularly in the setting of thickened endometrium and negative office biopsy. The procedure, consisting of TVU performed with sterile fluid placed in the uterine cavity, may show a thick endometrial stripe as secondary to diffuse endometrial thickening, focal endometrial thickening, polyp or other polypoid endometrial mass, or submucosal leiomyoma or other sessile or broad-based mass.

Diffusely thickened endometrium can be sampled by office biopsy or fractional curettage. Focal endometrial thickening and polypoid endometrial mass are candidates for sampling with the aid of hysteroscopy. However, some clinicians caution against the use of hysteroscopy unless absolutely necessary because of the potential for cancer cells to be pushed through the fallopian tubes into the peritoneal cavity. Whether this risk applies to a similar degree to hysterosonography remains to be determined.

In 25 cases of endometrial cancer reviewed by Atri et al, [66] tumors were hyperechoic relative to the myometrium in 76%, were isoechoic in 12%, and contained both hypoechoic and hyperechoic regions in 12% of patients. Approximately 40% of patients in this series had well-defined echogenic endometrial thickening that was not distinguishable from benign endometrial abnormalities such as hyperplasia or polyp. Cystic changes within thickened endometrium, previously suggested to be indicative of benign pathology (eg, hyperplasia or polyp), were found in 24% of patients with endometrial cancer.

Other sonographic findings include the following:

-

Broad-based polypoid mass expanding the endometrial cavity with or without surrounding fluid.

-

Endometrial polypoid mass protruding through the endocervical canal.

-

Large mass centrally in the uterus replacing the endometrial stripe.

-

Complex fluid collection in the endometrial cavity (secondary to malignant stenosis of the endocervical or endometrial canal) that may represent pyometra or hematometra.

-

Calcifications (uncommon in endometrial cancer).

TVU is useful for the evaluation of myometrial invasion by endometrial carcinoma. The demonstration of partial or total disruption of the hypoechoic subendometrial halo, formed by the compact and vascular inner myometrial region, usually reflects the presence of myometrial invasion, although depiction of intact subendometrial halo may be associated with superficial invasion or lack of invasion. The depth of myometrial invasion can be estimated by measuring, on sagittal images, the thickness of the tumor extending beyond the outer margin of the endometrium and dividing it by the entire thickness of the adjacent intact myometrium.

Patients with breast cancer on prolonged tamoxifen therapy have increased risk of developing endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. Some of these patients may actually have mixed histopathologic abnormalities.

The most common endometrial US abnormality associated with tamoxifen is a thickened endometrium showing multiple cystic foci. Other findings include homogeneous hyperechoic endometrial thickening and heterogeneous endometrial thickening. Tamoxifen-related endometrial changes are nonspecific and overlap in appearance with findings encountered in hyperplasia, polyps, and carcinoma detected in postmenopausal patients receiving tamoxifen or hormonal replacement therapy, as well as in patients not receiving therapy.

Degree of confidence

TVU is excellent for the evaluation of the endometrium and the contents of the endometrial cavity. TVU is superior to CT and approaches MRI in its ability to provide information regarding myometrial, cervical, and perhaps parametrial invasion by endometrial carcinoma. US has significantly lower sensitivity than CT in detecting enlarged abdominal and pelvic lymph nodes (particularly in the obese patient) and in depicting intraperitoneal, omental, and mesenteric metastases. CT also is superior to US in assessing pelvic sidewall extension and adjacent organ invasion.

No US feature can reliably differentiate between malignant and benign endometrial pathology in the absence of identifiable myometrial invasion. The reported overall accuracy of US in detecting myometrial invasion and distinguishing between superficial and deep myometrial invasion by endometrial carcinoma ranges from 69 to 90%. The reported sensitivity and specificity of US evaluation of the depth of myometrial invasion are 50-100% and 65-100%, respectively. The reported sensitivity and specificity of US evaluation of cervical invasion by endometrial carcinoma are 66.7-80% and 95.2-100%, respectively.

US limitations in the evaluation of endometrial carcinoma include the following:

-

Understaging cancers presenting with microscopic tumor spread.

-

Difficulty consistently differentiating endometrial cancer from benign pathologic findings.

-

Overestimation of the degree of myometrial invasion when a large exophytic endometrial tumor or a large amount of hemorrhagic debris expands the uterine cavity and considerably effaces or stretches the overlying myometrium.

-

Interpretation errors in the assessment of myometrial invasion in patients who lack a demonstrable subendometrial halo, in elderly patients who typically have a thin myometrium, and in the setting of a leiomyomatous uterus.

-

Diminished accuracy in assessing pelvic sidewall extension and adjacent organ invasion.

-

Low sensitivity in detecting enlarged lymph nodes and in depicting extrapelvic metastasis.

False positives/negatives

US findings of endometrial cancer are not specific and can be simulated by the following:

-

Adenomatous hyperplasia

-

Polyp(s)

-

Tamoxifen-related endometrial changes

-

Degenerating submucosal leiomyoma

-

Endometrial extension of cervical cancer

-

Blood clots

Positron Emission Tomography Imaging

PET/CT is not routinely employed in assessing intrauterine disease, but it can detect depth of myometrial invasion and extension into the endocervix. In general, if the baseline MRI or CT scan suggests enlarged nodes and removal of all positive nodes during primary surgery will offer a survival advantage, then PET‐CT may be helpful in detecting the most caudal metastatic lymph node. [33] PET/CT is more sensitive than CT or MR imaging for detection of nodal metastases. In patients with biopsy results demonstrating high-risk histology, PET/CT may be used to identify unsuspected distant disease. [7, 67]

In a prospective, multicenter trial, preoperative PET/CT detected the majority (31 of 48 [64.6%]) of distant metastases before treatment with high specificity and positive predictive value (PPV). Central reader PET/CT interpretation demonstrated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value of 64.6%, 98.6%, 86.1%, and 95.4%, respectively. [68]

-

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. Sagittal transvaginal ultrasound image of the uterus shows a central mass replacing the endometrial stripe, with hyperechoic and hypoechoic regions.

-

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. Transverse transvaginal ultrasound image of the uterus shows a central mass replacing the endometrial stripe, with hyperechoic and hypoechoic regions.

-

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4.0 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

-

A 76-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). CT image shows a relatively hypoattenuated mass in the region of the endometrial cavity. Diffuse myometrial thinning is evident. Surgical pathology revealed approximately 4 cm of pedunculated endometrial tumor associated with only superficial myometrial invasion (limited to inner one third).

-

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3. CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

-

A 63-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma, nuclear grade 3 (same patient as above). CT images through the upper uterus show tumor masses and minimal fluid expanding the endometrial cavity and causing marked myometrial thinning. Surgical pathology revealed predominantly exophytic polypoid tumor in the endometrial cavity and full-thickness myometrial invasion without extension to the serosal surface.

-

A 64-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with focal squamous differentiation. CT image shows tumor expanding the entire endometrial cavity. The myometrium is markedly thinned and its inner margins are ill defined. Surgical pathology confirmed tumor involvement of the cervix and the outer third of the myometrium.

-

A 64-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the endometrium with focal squamous differentiation (same patient as above). CT image shows tumor expanding the cervix. Surgical pathology confirmed tumor involvement of the cervix.

-

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type. CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

-

A 45-year-old woman with poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma of mixed cell type (same patient as above). CT image shows tumor replacing the entire endometrial cavity and extending into the endocervix. The myometrium is predominantly thinned at the fundus and its inner margins are ill defined. The serosal surface of the uterus is surrounded by soft tissue attenuation suggestive of parametrial tumor extension. Hysterectomy performed after chemotherapy confirmed tumor involvement of the lower uterine segment, the endocervix, and the outer third of the myometrium.

-

A 73-year-old woman with well-differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. CT image through the uterus shows fluid-filled cavity marginated by tumor involving most of the endometrial surface and the endocervical region. An enlarged lymph node is evident at the right pelvic sidewall.

-

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation. CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrium in the fundus is thin but well defined. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

-

A 74-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (same patient as above). CT image shows a markedly distended endometrial cavity containing soft tissue attenuation material in the dependent region and fluid superiorly, resulting in a fluid/debris level. The myometrial and endometrial regions in the lower uterus are ill defined and slightly heterogeneous. Surgical pathology revealed hemorrhagic fluid in the distended endometrial cavity and stenosis at the junction of the endocervical canal and the endometrium secondary to the endometrial tumor predominantly involving the lower uterine segment and extending deep into the cervical stroma.

-

A 57-year-old woman with stage IVB poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. CT image through the mid pelvis. The upper uterus shows confluent soft tissue masses and fluid expanding the endometrial cavity, diffuse myometrial thinning consistent with deep myometrial invasion, and parametrial tumor extension through the disrupted myometrium at the right fundal region. The patient had multiple pulmonary metastases, which is indicative of stage IVB disease.

-

A 57-year-old woman with stage IVB poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. CT image through the lower pelvis. The cervix is markedly enlarged and replaced by tumor. The patient had multiple pulmonary metastases, which is indicative of stage IVB disease.

-

A 57-year-old woman with stage IVB poorly differentiated endometrial carcinoma. CT image through the lower thorax shows multiple pulmonary metastases, small pericardial effusion, and small bilateral pleural effusions.

-

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma. Axial T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the right side of the endometrium and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

-

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted MR image of the uterus shows a multilobulated, low signal intensity, polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer and surrounded by fluid. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

-

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T1-weighted image of the uterus, following the administration of gadolinium, shows mild contrast enhancement of polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images, consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.

-

An 83-year-old woman with moderately differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma (same patient as above). Sagittal T2-weighted image of the uterus without gadolinium shows slightly hyperintense polypoid tumor arising from the anterior endometrial layer. The tumor size is underestimated secondary to the surrounding isointense fluid markedly distending the endometrial cavity; the fluid is hyperintense on T1- and T2-weighted images and is consistent with hematometra. Examination under anesthesia revealed significant benign stenosis of the atrophic cervix. Dilatation and curettage confirmed the fluid to be old blood and established the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy. Note that the marked myometrial thinning, due to both the elderly age and the marked distension of the uterine cavity, limits the assessment of myometrial invasion.