Practice Essentials

Duodenal ulcers are part of a broader disease state categorized as peptic ulcer disease. Peptic ulcer disease refers to the clinical presentation and disease state that occurs when there is a disruption in the mucosal surface at the level of the stomach or the first part of the small intestine—the duodenum. Ulceration results from damage to the mucosal surface that extends beyond the superficial layer. Most duodenal ulcers present with dyspepsia as the primary associated symptom, but presentation can range in severity and may include gastrointestinal bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction, perforation, or fistula development. Management is highly dependent on the patient's presentation at the time of diagnosis or on disease progression. Patients with dyspepsia/upper abdominal pain symptoms may report a history of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use or previous Helicobacter pylori infection. [1]

Duodenal ulcers (DUs) affect nearly 10% of the adult population at some point in life, [2] and these lesions account for two thirds of all peptic ulcers, which are defined as mucosal breaks of 3 mm or greater; gastric ulcers account for the rest. Unlike gastric ulcers, which may be malignant in about 5% of cases, [2] duodenal ulcers are almost invariably benign; therefore, treatment with antisecretory drugs can be commenced after radiologic diagnosis, without endoscopy performed beforehand. [3, 4]

(Images of duodenal ulcers are provided below.)

Imaging modalities

Once the diagnosis of H. pylori is considered a possibility on the basis of a history of presenting illness and physical exam findings, studies are necessary to establish a definite diagnosis and underlying cause. [1] Endoscopy has become the diagnostic procedure of choice for patients with suspected duodenal ulcer. However, endoscopy is more invasive and costly than double-contrast barium study. Double-contrast examinations of the upper gastrointestinal tract remain a useful alternative to endoscopy but have lower sensitivity, especially in detection of small duodenal ulcers. [5, 6, 7] Endoscopy with biopsy has a sensitivity as high as 95%, but small ulcers in the base of the duodenal bulb may be missed. In the presence of gastric outlet or proximal duodenal obstruction, the endoscope may be unable to pass through the stenosis, and the full extent and the cause of the obstruction may not be defined.

Although endoscopy is the diagnostic method used most often to assess the lumen of the upper gastrointestinal tract, fluoroscopy is a valuable adjunct technique and is the study of choice for many diseases, specifically those for which anatomic and functional information is required. Fluoroscopy is also commonly used postoperatively to assess for complications such as obstruction and extraluminal leaks. Compared with endoscopy, fluoroscopy is an inexpensive and noninvasive technique that provides salient anatomic information along with delineation of the duodenal mucosa and assessment of real-time duodenal motility. [8]

Single-contrast barium studies may cause as many as 40% of small ulcers to be missed, but double-contrast barium images depict as many as 95% of ulcers larger than 10 mm [2] ; these results are comparable to those of endoscopy. However, the sensitivity of double-contrast barium examination decreases with smaller ulcers and recurrent ulcers in a deformed duodenal bulb; therefore, this modality is not reliable for detection of duodenitis or duodenal erosions. Another disadvantage of barium studies is that biopsy specimens cannot be obtained to test for H pylori infection or to evaluate a suspicious lesion. [9, 10]

The differential diagnosis includes acalculous cholecystitis, acute cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, Crohn disease, gastric ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, acute and chronic pancreatitis, Gastrointestinal tuberculosis, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Failure to diagnose duodenal ulceration and the complications of duodenal ulceration (eg, hemorrhage, gastric outlet obstruction, perforation) are special concerns. [11, 12, 13, 14] Computed tomography performed for evaluation of abdominal pain can identify nonperforated peptic ulcers. However, most patients will need a referral for esophagogastroduodenoscopy for further evaluation. [1]

In one study, esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed that complicated duodenal ulcer disease was accompanied by a significantly higher detection rate of erosive esophagitis (20%), gastritis (52%), duodenitis (25%), multiple ulcers (28%), and larger ulcer size. [14]

Radiologic intervention

Transcatheter embolization may be used to treat bleeding duodenal ulcers. [15] Terminal muscular-branch vessel embolization is more effective than gastroduodenal artery embolization in initial and long-term control of bleeding. Terminal vessels may be occluded with 6-cyanoacrylate, but duodenal stenosis is a late complication in 25%of all patients.

In a study of 29 patients with massive bleeding from duodenal ulcer disease, 26 patients achieved immediate hemostasis with emergency transcatheter arterial embolization, and the technical success rate reached 90%. No hemostasis was observed in 27 patients within 30 days after emergency transcatheter arterial embolization, and the clinical success rate was 93%. [16]

Fluoroscopically guided balloon (15 or 20 mm in diameter) dilatation may be used for benign duodenal strictures caused by peptic ulcers, Crohn disease, or postoperative adhesion. [17] Duodenal perforation may occur, necessitating emergency surgery.

Radiography

Most duodenal ulcers are depicted as round or ovoid pools of barium; about 5% may be linear, and most are smaller than 1 cm in diameter. Giant duodenal ulcers, defined as those larger than 2 cm in diameter, are at increased risk of perforation, obstruction, and bleeding. Multiple ulcers occur in about 15% of patients [2] ; Zollinger-Ellison syndrome should be considered in these patients.

About 95% of duodenal ulcers occur in the duodenal bulb, [2] and the rest occur in the postbulbar duodenum, which consists of the proximal 2 cm of the descending duodenum above the ampulla of Vater. As many as half of all duodenal ulcers occur in the anterior wall of the bulb.

Technique of double-contrast barium study

Biphasic examination combines the advantages of double-contrast views of the duodenum with use of high-density barium. Advantages include prone or erect compression views when low-density barium is used to show ulcers in the anterior wall of the bulb. Intravenous (IV) glucagon 0.1 mg and effervescent granules are administered as part of the double-contrast examination; this is followed by acquisition of single-contrast compression views with low-density barium.

Bulbar ulcers

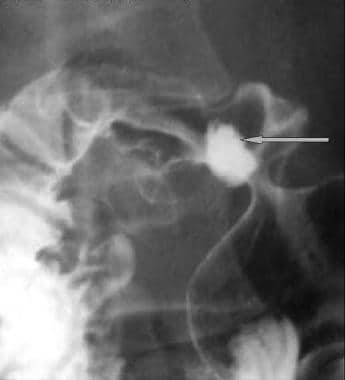

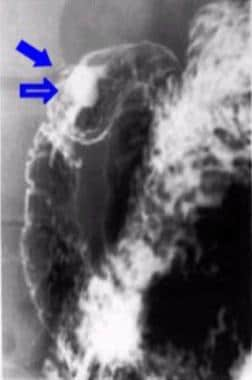

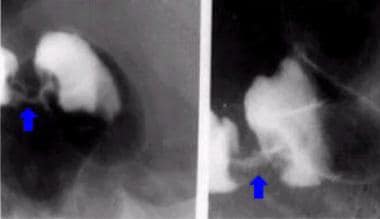

Bulbar ulcer craters are depicted as well-defined round or ovoid pools of barium that can be seen en face or in profile (see the images below); they are often surrounded by a smooth mound of edematous mucosa.

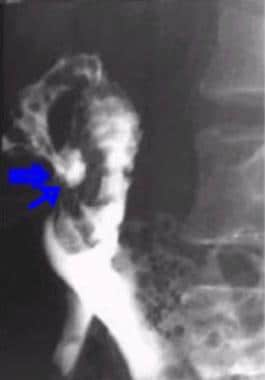

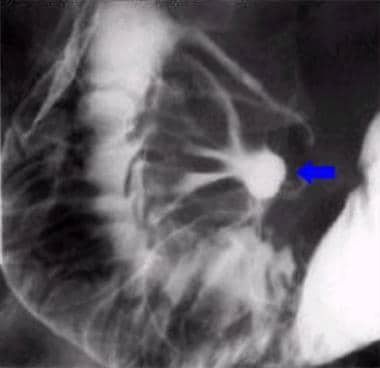

Radiating folds converge to the edge of the crater, as shown in the first image below. Ulcers in the anterior wall may be detected as a ring shadow, as seen in the second image below, with barium coating the edge of the unfilled ulcer crater. These craters are filled on prone or erect compression views.

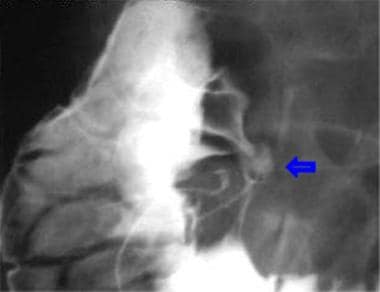

The duodenal bulb is often deformed by edema and spasm associated with the ulcer or by scarring from a previous ulcer (see the following images). Small ulcers may not be detected in a deformed bulb.

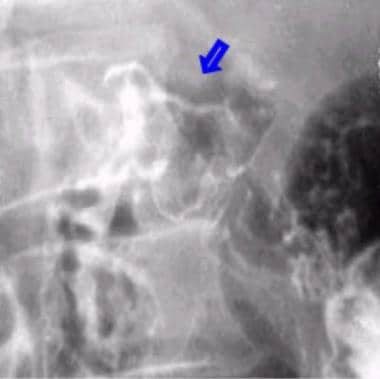

Postbulbar ulcers

Postbulbar ulcers are usually located in the medial wall of the proximal descending duodenum above the ampulla of Vater (see the images below) and are prone to bleeding. Detection of the ulcer niche or crater is often difficult because of associated edema and spasm, which may also cause indentation of the lateral wall of the descending duodenum opposite the ulcer. This indentation may lead to stricture formation as a result of fibrosis and may mimic a carcinoma of the duodenum.

Ulcer healing

Healing is often rapid, with a decrease in the size of the ulcer and a change from a round to a linear configuration. Healing may lead to scarring, with radiating mucosal folds converging to the site of the previous ulcer. Bulbar deformity results from asymmetric scarring and retraction during healing (see the following images). Pseudodiverticula result from expansion of normal segments of the cap between areas of fibrosis. If present, the typical cloverleaf appearance of the scarred bulb is caused by formation of multiple pseudodiverticula.

Complications of duodenal ulceration

Hemorrhage occurs in 20-30% of ulcers. [2] Endoscopy is the investigation of choice, with sensitivity greater than 90% for detection of the bleeding site. [2] Double-contrast barium studies are limited by poor mucosal coating in the presence of bleeding. Nevertheless, the bleeding site may be detected in as many as 75% of cases. [2] A filling defect resulting from a blood clot, food debris, or granulation tissue may be seen at the base of the barium-filled ulcer.

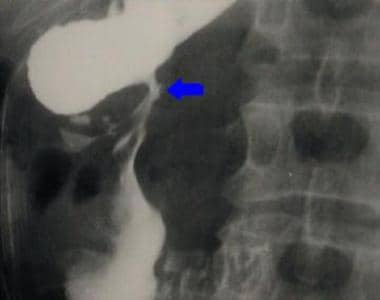

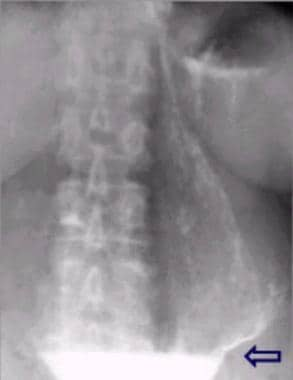

Gastric outlet obstruction occurs in 5% of patients with peptic ulcers. [2] It is most common in duodenal ulcers but also occurs in antral or pyloric channel ulcers. Peptic ulcers account for two thirds of cases of gastric outlet obstruction in adults. [2] Images typically show narrowing and deformity of the pylorus or the duodenal cap, as seen in the image below.

Nasogastric suction of the large gastric residue (see the following image) may be required before the upper gastrointestinal series is performed.

Large volume of residual gastric juice in gastric outlet obstruction. Note the fluid level (arrow) between the barium and gastric juice. Nasogastric aspiration before radiographic examination aids assessment of these cases.

Large volume of residual gastric juice in gastric outlet obstruction. Note the fluid level (arrow) between the barium and gastric juice. Nasogastric aspiration before radiographic examination aids assessment of these cases.

The descending duodenum may be obstructed by fibrosis caused by a postbulbar ulcer, as can be seen in the second image below.

Less common causes of gastric outlet (or proximal duodenal) obstruction include malignancy (see the first image below) such as carcinoma of the duodenum (see the second image below); large duodenal adenomas (see the third image below); Crohn disease; tuberculosis; mural hematoma; and extrinsic compression caused by pancreatic lesions.

Obstruction as a result of marked narrowing of the first and second parts of the duodenum. Laparotomy demonstrated malignant infiltration of the duodenum caused by adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder.

Obstruction as a result of marked narrowing of the first and second parts of the duodenum. Laparotomy demonstrated malignant infiltration of the duodenum caused by adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder.

Upper gastrointestinal series. Annular shouldered stricture caused by carcinoma in the second part of the duodenum.

Upper gastrointestinal series. Annular shouldered stricture caused by carcinoma in the second part of the duodenum.

Perforation occurs in as many as 10% of patients with peptic ulcer disease, [2] most of which arise from ulcers in the anterior aspect of the duodenal cap. In 75% of cases, free gas is present in the peritoneum [2] ; this is best shown on an erect chest radiograph, as demonstrated in the image below. A water-soluble contrast upper gastrointestinal series may reveal the presence and site of perforation, or whether it has sealed.

Subphrenic collections are common sequelae of a perforated duodenal ulcer. Occasionally, they may be shown on an erect chest radiograph (see the first image below), but these collections are best assessed with ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) scanning (see the second image below). [11]

A gas-fluid level is seen under the right diaphragm as a result of a subphrenic collection caused by a perforated duodenal ulcer.

A gas-fluid level is seen under the right diaphragm as a result of a subphrenic collection caused by a perforated duodenal ulcer.

Penetrating posterior wall duodenal ulcers result in a walled-off perforation. An abscess may form in the lesser sac, and the pancreas is involved in two thirds of cases. [2]

The incidence of complicated peptic ulcer disease has decreased over the past few decades, but it remains a condition associated with significant mortality. Diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer disease in morbidly obese patients can be challenging, and patients with excluded segments—such as those who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)—present an even greater problem, as the subsequent altered anatomy impedes use of common modalities for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Patients with perforation after RYGB usually present without signs of hollow organ perforation on clinical examination but also on computed tomography scans. Diagnostic laparoscopy can be performed to address the discrepancy between pain and nondiagnostic examinations. An aggressive approach in cases of unexplained symptoms is not only justified but mandatory. [18]

Fistulas may be also be present. [19] Duodenocolic fistulas are usually caused by invasion of the second part of the duodenum by a carcinoma of the hepatic flexure or ascending colon. Rarely, these lesions may result from a penetrating ulcer of the duodenal bulb or postbulbar region that has caused erosion into the adjacent colon. In addition, choledochoduodenal fistulas may occur. [19] About 95% are associated with complications of biliary tract calculi. Only 5% are caused by duodenal ulcers that cause erosion into the common bile duct. Abdominal radiographs may show gas in the biliary tree.

Acute gastrointestinal bleeding is a life-threatening medical emergency with high morbidity and mortality. Transcatheter embolization with endovascular coils performed under digital subtraction angiography guidance is a common and effective method for treatment associated with high technical success rates. Duodenal ulcer may be caused by coils wiggled from a branch of the gastroduodenal artery after interventional therapy. This rare complication requires careful attention, effective precautionary measures, and more secure alternative treatment methods. [20]

Degree of confidence

Single-contrast barium studies may cause as many as 40% of small ulcers to be missed, but double-contrast barium images depict as many as 95% of ulcers larger than 10 mm; these results are comparable with those of endoscopy. However, the sensitivity of double-contrast barium examination decreases with smaller ulcers and recurrent ulcers in a deformed duodenal bulb. Double-contrast barium examination is not reliable for detection of duodenitis or duodenal erosions.

False positives/negatives

Ulcers may be obscured by edema, spasm, or scarring. False-positive results are caused by pseudodiverticula and small pools of barium in a deformed bulb resulting from previous peptic ulceration.

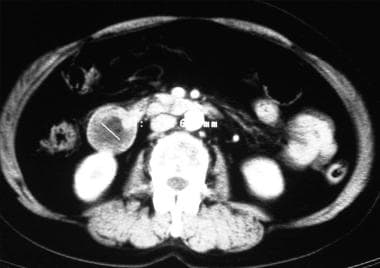

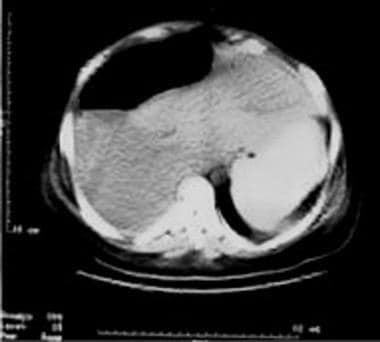

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scanning plays a small role in the primary detection of duodenal ulcers. However, primary inflammatory processes of the duodenum such as ulcers, duodenitis, and secondary involvement from pancreatitis can be diagnosed reliably with CT scanning. [21] Careful CT scanning technique and 3-dimensional (3-D) imaging can help optimize detection of abnormalities and disease and can facilitate surgical planning. These include the use of oral contrast, preferably water, as well as IV contrast. [12, 22] CT scanning also plays a role in detection of subphrenic and other collections that may occur after perforation of a duodenal ulcer (see the image below). [23]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography may indicate the presence of a giant duodenal ulcer. Its main role is detection of other causes of upper abdominal pain, such as that caused by gallstones and pancreatitis. This modality also depicts subphrenic and other collections resulting from a perforated duodenal ulcer.

Direct ultrasound imaging findings alone have a low sensitivity for diagnosing duodenal (65%) and gastric (40%) ulcers. [24] Weston and colleagues reported that the utility of abdominal ultrasound as the sole modality for detecting nonperforated gastroduodenal ulcers is poor. They recommend the use of additional modalities when ulcerative lesions are suspected. [25]

-

Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal series. Posterior wall duodenal ulcer.

-

Lateral view of a posterior wall ulcer in the same patient as in the previous image.

-

Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal series. Anterior wall ulcer in a duodenal cap.

-

Lateral view of an anterior wall duodenal ulcer in the same patient as in the previous image.

-

Duodenal cap ulcer in a patient with a short history of symptoms.

-

Deformity of duodenal cap caused by recurrent ulceration. Single-contrast view.

-

Double-contrast view in the same patient as the previous image.

-

Postbulbar ulcer.

-

Single-contrast view in the same patient as the previous image.

-

Gastric outlet obstruction caused by deformed duodenal cap from recurrent peptic ulceration.

-

Large volume of residual gastric juice in gastric outlet obstruction. Note the fluid level (arrow) between the barium and gastric juice. Nasogastric aspiration before radiographic examination aids assessment of these cases.

-

Obstruction as a result of marked narrowing of the first and second parts of the duodenum. Laparotomy demonstrated malignant infiltration of the duodenum caused by adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder.

-

Upper gastrointestinal series. Annular shouldered stricture caused by carcinoma in the second part of the duodenum.

-

Computed tomography scan showing a large 2-cm adenoma in the descending part of the duodenum.

-

Chest radiograph. Free gas under the diaphragm caused by a perforated duodenal ulcer.

-

A gas-fluid level is seen under the right diaphragm as a result of a subphrenic collection caused by a perforated duodenal ulcer.

-

This computed tomography scan shows a large, right subphrenic collection.