Practice Essentials

Cancer of the uterine cervix (cervical cancer) is largely a preventable disease that is characterized by a long lead time. Precancerous lesions gradually progress through recognizable stages before developing into invasive disease (as demonstrated in the images below). [1, 2, 3] The disease process is almost certainly curable if it is identified before its progression to invasive cancer. [4] However, invasive cervical cancer remains a disease of significant morbidity, and it is a major cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide, although the incidence and mortality rates of invasive cervical cancer have declined substantially (particularly in countries that have well-developed screening programs). [5, 6] Cancer of the cervix in its early stages is readily managed with surgery. Radiation or chemoradiation therapies are reserved for high-risk early stages or advanced disease. [7]

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is now recognized as the most important causative agent in cervical carcinogenesis at the molecular level, although HPV may not induce many of the identified molecular alterations. [8, 9]

As many as 5% of cervical cancers may not be associated with HPV. [10, 11] First intercourse at an early age, sexual promiscuity, high parity, race, and low socioeconomic status are thought to increase the risk for cervical cancer because these factors are linked to sexual behavior that increases the likelihood of exposure to HPV and/or because they are cofactors that modify the risk in women who are infected with HPV. Tobacco smoking is also a significant independent risk factor.

Guidelines on cervical cancer screening have been issued by a number of organizations, including the American Cancer Society, American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American College of Physicians, American Society of Clinical Pathology, American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

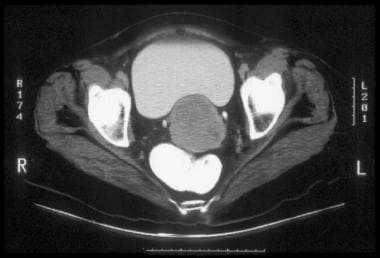

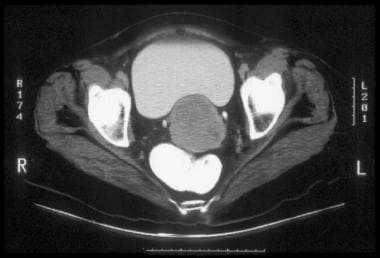

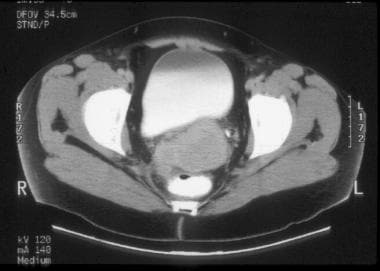

CT of clinically visible carcinoma confined to the cervix (stage IB). The image shows a mass with slightly heterogeneous attenuation that expands the cervix and is surrounded by a thin rim of relatively preserved stroma. The cervical margins are smooth, well defined, and intact. Parametrial soft-tissue stranding or masses are lacking, and the periureteral fat planes are preserved.

CT of clinically visible carcinoma confined to the cervix (stage IB). The image shows a mass with slightly heterogeneous attenuation that expands the cervix and is surrounded by a thin rim of relatively preserved stroma. The cervical margins are smooth, well defined, and intact. Parametrial soft-tissue stranding or masses are lacking, and the periureteral fat planes are preserved.

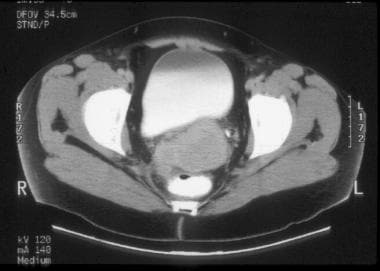

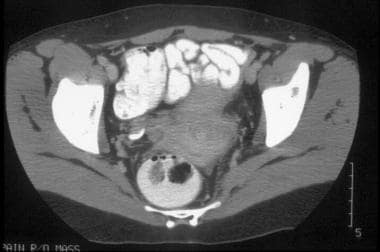

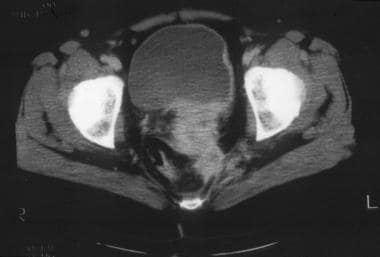

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a hypoattenuating tumor occupying the entire cervix and extending to the outer posterior and right cervical margins. This finding is consistent with full-thickness stromal invasion. Minimal air in the center is related to the biopsy. A vaginal tampon is present to the right of the cervix.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a hypoattenuating tumor occupying the entire cervix and extending to the outer posterior and right cervical margins. This finding is consistent with full-thickness stromal invasion. Minimal air in the center is related to the biopsy. A vaginal tampon is present to the right of the cervix.

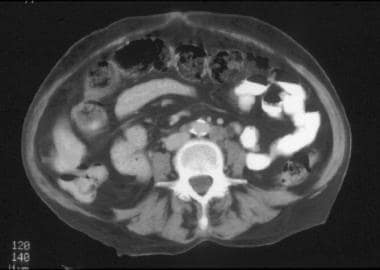

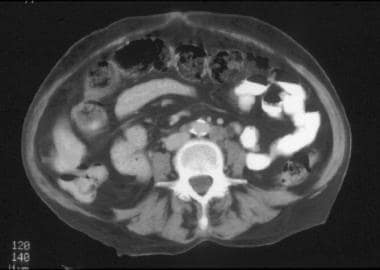

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma. This image of the mid abdomen shows borderline enlarged lymph node in the left para-aortic region, presumably secondary to metastasis, which is consistent with stage IVB disease. Multiple findings are visualized in this patient in other anatomic regions (please see the images below included in Stage IVB CT findings).

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma. This image of the mid abdomen shows borderline enlarged lymph node in the left para-aortic region, presumably secondary to metastasis, which is consistent with stage IVB disease. Multiple findings are visualized in this patient in other anatomic regions (please see the images below included in Stage IVB CT findings).

Preferred examination

The pretreatment evaluation of patients with cervical cancer includes physical examination, chest radiography, and intravenous urography (IVU) or cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography [CT] scanning or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). In early stage disease with a small tumor confined to the cervix, IVU and cross-sectional imaging are not routinely performed because of their relatively low yield. [20]

IVU is not needed when cross-sectional imaging is performed, because both modalities are similarly accurate in depicting urinary obstruction and because cross-sectional imaging has the additional ability to depict a gross tumor that involves the urinary tract. Barium enema examination, radioisotope bone scanning, cystoscopy, and proctosigmoidoscopy have a low yield, particularly in early disease, and these procedures are performed for only specific indications that are based on the symptoms or clinical findings. [21, 22]

MRI has excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution, which exceeds that of CT scanning and ultrasonography (US). [23, 24] Consequently, MRI is significantly more valuable than CT and US in the assessment of the size of the tumor, the depth of the cervical invasion, and the locoregional extent of the disease (direct invasion of the parametrium, pelvic sidewall, bladder, or rectum).

CT scanning and MRI are approximately equivalent, and both are significantly superior to US, in the detection of enlarged lymph nodes. [25] Overall, CT scanning and MRI are more accurate staging modalities than US. Furthermore, US is not suited for staging of the full extent of the tumor spread because of the inability of this technique to adequately depict all the potential sites of metastasis or the anatomic regions that contain lymph nodes.

Despite the advantages of MRI, the gynecology literature mostly recommends the use of CT scanning for the pretreatment evaluation of cervical cancer. [26] Reportedly, the additional information provided with the excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution of MRI often has no significant effect on clinical decision making or on the choice of therapy. [27]

In general, CT scanning and MRI are not warranted in patients with small-volume, early disease (stage Ib disease and a cervical tumor diameter < 2.0 cm) because of the low probability of parametrial invasion and nodal metastasis. Imaging with CT scanning or MRI is appropriate when the cervical tumor is larger than 2.0 cm, when the size of the tumor cannot be adequately evaluated during the clinical examination, or when the tumor is endocervical.

A small study found that whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging can distinguish normal uterine cervix from uterine cervical carcinoma and metastatic nodes from benign nodes. [28]

Clinical staging

The most commonly used staging system for cervical cancer was developed by the Féderation Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO). [29] The revised FIGO staging of carcinoma of the cervix uteri allows incorporation of imaging and/or pathological findings and clinical assessment of tumor size and disease extent. In stage I, the definition of microinvasion and lesion size is revised as follows:

-

Stage IA: lateral extension measurement is removed.

-

Stage IB has 3 subgroups-stage IB1: invasive carcinomas ≥5 mm and < 2 cm in greatest diameter.

-

Stage IB2: tumors 2-4 cm; stage IB3: tumors ≥4 cm.

-

Imaging or pathology findings may be used to assess retroperitoneal lymph nodes; if metastatic, the case is assigned stage IIIC; if only pelvic lymph nodes, the case is assigned stage IIIC1; if para-aortic nodes are involved, the case is assigned stage IIIC2.

The following amendments to the staging classification of carcinoma of the cervix uteri were made by the FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology in 2018 [29] :

-

Allowing the use of any imaging modality and/or pathological findings for allocating the stage.

-

In stage I, amendments to microscopic pathological findings and to size designations, allowing the use of imaging and/or pathological assessment of the size of the cervical tumor.

-

In stage II, allowing the use of imaging and/or pathological assessment of size and extent of the cervical tumor.

-

In stages I through III, allowing assessment of retroperitoneal lymph nodes by imaging and/or pathological findings and, if deemed metastatic, the case is designated as stage IIIC (with notation of method used for stage allocation).

-

No recommendations for routine investigations, which are to be decided on the basis of clinical findings and standard of care.

According to the FIGO committee, the revised staging system does not mandate the use of a specific imaging technique, lymph node biopsy, or surgical assessment of the extent of tumor. In low‐resourced conditions, clinicians can continue to assess the patient clinically as before. The size of the primary tumor can be assessed by clinical evaluation (preoperative or intraoperative), imaging, and/or pathological measurement. Identification of lymph node metastasis should be accomplished using any imaging technique(s) and/or pathological assessment methods available to the provider, and the choice of technique is theirs. It is recommended that the method used for imaging (eg, ultrasound, computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], positron emission tomography [PET], PET‐CT, MRI‐PET, etc.) and/or the pathological technique used (eg, evaluation of the operative specimen, lymph node biopsy, or fine needle aspiration cytology), and the results thereof, should be recorded, so that subsequent data analysis can be performed. [29]

Additional staging

Extended clinical staging with cross-sectional imaging (CT and/or MRI), PET/CT when clinically appropriate, and surgicopathologic staging, including pelvic and abdominal retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy, provide additional diagnostic value. [30]

Each has been proven to be superior to the conventional FIGO clinical staging system in determining the full extent of the tumor spread. However, once the clinical stage is assigned on the basis of the clinical pretreatment workup results (in compliance with the FIGO guidelines), the stage should not be altered as a result of subsequent findings. Instead, any additional information that is revealed by cross-sectional imaging or surgery is primarily used for planning treatment regimens, and they should not be used to revise the assigned clinical stage.

Limitations of techniques

CT uses ionizing radiation and the CT image quality is degraded by metallic prostheses, an extremely large body habitus, and patient or respiratory motion. The use of intravenous iodinated contrast material for CT imaging is associated with a risk of significant allergic reactions (including fatal anaphylaxis), nephrotoxicity, and complications due to its extravasation into the soft tissues at the injection site.

MRI is contraindicated in patients who have vital metallic biomedical devices or metallic objects in strategic anatomic regions. MRI is more costly and less readily available than CT and requires long image acquisition times. The image quality is degraded by artifacts related to respiratory motion and bowel peristalsis, which are likely to occur during the long image acquisition time. No effective GI contrast material is currently available for MRI. Claustrophobia deters some patients from undergoing MRI.

US is operator dependent. The image quality is degraded by a large body habitus, and visualization of portions of the pelvis and abdomen is precluded by bowel gas and bony structures. The transabdominal approach is also influenced by the degree of bladder filling and is impeded by the presence of surgical incisions, dressings, drains, or skin lesions. Transvaginal and transrectal US probes have inherent limitations, including small field of view, a short range of target penetration with high-frequency transducers, and occasional patient intolerance of the transvaginal or transrectal approach.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT is the imaging modality that is most commonly used in clinical practice to evaluate the extent of spread of cervical cancer. The oral, rectal, or intravenous administration of contrast material is necessary for optimal CT evaluation (unless a contraindication exists). The intravenous injection of contrast material is particularly useful in increasing the conspicuity of the cervical tumor and in facilitating the evaluation of the parametria and the pelvic sidewalls. [31, 32, 33, 34]

General CT findings

The normal uterine cervix is an ovoid or round structure with homogeneous soft-tissue attenuation. The cervix shows peripheral enhancement on the earliest images that are obtained with the intravenous administration of contrast material using a power injector. The contrast enhancement rapidly becomes diffuse and uniform throughout the cervix, but it may not be as intense as the myometrial enhancement because of the preponderance of fibrous tissues in the cervical stroma. The cervix is anecdotally described to be generally smaller than 3 cm in diameter.

Cervical cancer and the normal cervical stroma usually have similar attenuations on CT images that are obtained without intravenous contrast enhancement. Therefore, the tumor and the normal cervical parenchyma cannot be reliably distinguished on nonenhanced CT scans, and the cervix may have a normal CT appearance. Alternatively, the only detectable finding may be an enlarged cervix with homogeneous attenuation and regular or irregular contours.

After the intravenous administration of contrast material, the manifestations of cervical cancer include the following:

-

A cervix with a normal CT appearance

-

An enlarged cervix with normal contrast enhancement

-

An enlarged cervix with inhomogeneous areas of hypoattenuation but without a discrete mass that is clearly delineated or definitely evident (see the image below)

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right side. The cervix is diffusely enlarged and shows subtle hypoattenuation, but the tumor margins are not clearly delineated.

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right side. The cervix is diffusely enlarged and shows subtle hypoattenuation, but the tumor margins are not clearly delineated.

-

An enlarged cervix with a circumscribed solid mass that has an enhancement that is less than that of the normal cervical stroma and shows a homogeneous or heterogeneous hypoattenuation (see the images below)

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a hypoattenuating tumor occupying the entire cervix and extending to the outer posterior and right cervical margins. This finding is consistent with full-thickness stromal invasion. Minimal air in the center is related to the biopsy. A vaginal tampon is present to the right of the cervix.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a hypoattenuating tumor occupying the entire cervix and extending to the outer posterior and right cervical margins. This finding is consistent with full-thickness stromal invasion. Minimal air in the center is related to the biopsy. A vaginal tampon is present to the right of the cervix.

This CT image demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node at the left pelvic sidewall, a finding that is consistent with pelvic lymph node metastasis, which is indicative of stage IIIB disease. The cystic consistency is not unusual for metastatic cervical carcinoma. The primary tumor is well depicted as a hypoattenuating, circumscribed mass. A cyst is present in the anteriorly located left ovary.

This CT image demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node at the left pelvic sidewall, a finding that is consistent with pelvic lymph node metastasis, which is indicative of stage IIIB disease. The cystic consistency is not unusual for metastatic cervical carcinoma. The primary tumor is well depicted as a hypoattenuating, circumscribed mass. A cyst is present in the anteriorly located left ovary.

The hypoattenuation of the mass may be a manifestation of the inherent properties or vascularity of the tumor tissue. Areas of necrosis or ulceration are common and are depicted as foci of accentuated low attenuation in the hypoattenuating mass.

Collections of air are sometimes evident in the mass, and they may be the result of a recent surgical biopsy, tumor necrosis, or infection (see the image below).

CT of a large, lobulated mass that is replacing the cervix and showing nonuniform hypoattenuation. The air and fluid in the center of the mass are consistent with tumor necrosis and a complicating infection (the patient had purulent discharge). The central hypoattenuation in the uterine corpus is suggestive of minimal fluid in the cavity.

CT of a large, lobulated mass that is replacing the cervix and showing nonuniform hypoattenuation. The air and fluid in the center of the mass are consistent with tumor necrosis and a complicating infection (the patient had purulent discharge). The central hypoattenuation in the uterine corpus is suggestive of minimal fluid in the cavity.

Cervical cancer frequently obstructs the endocervical canal, resulting in accumulation of serous, hemorrhagic, or purulent fluid in the uterine cavity (see the image below).

CT image through the upper uterus shows fluid that markedly distends the endometrial cavity secondary to obstruction of the endocervical canal by cervical cancer. A small submucosal leiomyoma projects into the right anterior aspect of the endometrial cavity and has minute calcifications.

CT image through the upper uterus shows fluid that markedly distends the endometrial cavity secondary to obstruction of the endocervical canal by cervical cancer. A small submucosal leiomyoma projects into the right anterior aspect of the endometrial cavity and has minute calcifications.

Because CT scanning does not consistently allow the direct visualization of the primary tumor, an evaluation of the size of the tumor and the depth of stromal penetration is precluded in many patients.

The evaluation of the lymph nodes is based on morphologic size criteria. Pelvic, abdominal-retroperitoneal, celiac axis, and mesenteric lymph nodes greater than 1.0 cm in their short axis are considered enlarged.

The occasional detection of intranodal necrosis is most consistent with metastasis; this necrosis is best depicted on contrast-enhanced images as hypoattenuation focus.

The extended clinical staging of cervical carcinoma with cross-sectional imaging (CT and/or MRI) is based on the FIGO criteria (see below).

Stage I CT findings

Preclinical invasive cervical carcinoma (stage IA) is not detectable by CT.

Clinically visible tumors limited to the cervix (stage IB) are isoattenuating relative to the normal cervical stroma in as many as 50% of patients. As such, the cervix may have a normal CT scan appearance, or the only detectable finding may be an enlarged cervix with homogeneous attenuation. Alternatively, the enlarged cervix may show inhomogeneous areas of hypoattenuation or a hypoattenuating solid mass (as described above).

The CT features of invasive cancer confined to the cervix (stage I) also include the following (see the image below): smooth, well-defined, and intact peripheral cervical contours; lack of parametrial soft-tissue strands or masses; and preservation of the periureteral fat planes.

CT of clinically visible carcinoma confined to the cervix (stage IB). The image shows a mass with slightly heterogeneous attenuation that expands the cervix and is surrounded by a thin rim of relatively preserved stroma. The cervical margins are smooth, well defined, and intact. Parametrial soft-tissue stranding or masses are lacking, and the periureteral fat planes are preserved.

CT of clinically visible carcinoma confined to the cervix (stage IB). The image shows a mass with slightly heterogeneous attenuation that expands the cervix and is surrounded by a thin rim of relatively preserved stroma. The cervical margins are smooth, well defined, and intact. Parametrial soft-tissue stranding or masses are lacking, and the periureteral fat planes are preserved.

Stage IIB CT findings

The CT features of parametrial tumor invasion (stage IIB) include the following (in order of increasing positive predictive value [PPV]): loss of definition, irregularity, or nodularity of the cervical contours; increased attenuation and prominent or thick soft-tissue strands in the parametrial and/or periureteral fat (see the first 2 images below); confluent soft tissue that replaces the periureteral fat (see the third image below); and an eccentric, 3-dimensional (3D) parametrial soft-tissue mass (see the fourth and fifth images below).

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated. In addition, a subserosal leiomyoma protrudes from the left side of the uterus.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated. In addition, a subserosal leiomyoma protrudes from the left side of the uterus.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. Parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by soft-tissue attenuation that replaces the periureteral fat on the right.

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. Parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by soft-tissue attenuation that replaces the periureteral fat on the right.

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right and extends into the anterior and right-sided rectal walls.

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right and extends into the anterior and right-sided rectal walls.

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right side. The cervix is diffusely enlarged and shows subtle hypoattenuation, but the tumor margins are not clearly delineated.

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right side. The cervix is diffusely enlarged and shows subtle hypoattenuation, but the tumor margins are not clearly delineated.

Stage III CT findings

In stage IIIA, the tumor extends into the lower one third of the vagina, without spread to the pelvic sidewall. In stage IIIB, the tumor extends into the pelvic sidewall, and/or there is a nonfunctioning kidney or hydronephrosis due to invasion of the ureter. The depiction of enlarged pelvic lymph nodes on CT scans is considered equivalent to pelvic sidewall tumor extension (see the image below).

This CT image demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node at the left pelvic sidewall, a finding that is consistent with pelvic lymph node metastasis, which is indicative of stage IIIB disease. The cystic consistency is not unusual for metastatic cervical carcinoma. The primary tumor is well depicted as a hypoattenuating, circumscribed mass. A cyst is present in the anteriorly located left ovary.

This CT image demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node at the left pelvic sidewall, a finding that is consistent with pelvic lymph node metastasis, which is indicative of stage IIIB disease. The cystic consistency is not unusual for metastatic cervical carcinoma. The primary tumor is well depicted as a hypoattenuating, circumscribed mass. A cyst is present in the anteriorly located left ovary.

CT features of pelvic sidewall tumor invasion (stage IIIB) include the following: a parametrial tumor within 2-3 mm of the pelvic sidewall; irregular, thick, soft-tissue strands or confluent soft tissues that extend through the parametrium to the obturator internus muscle or piriformis muscle (see the image below in stage IVA); a confluent mass that incorporates the pelvic sidewall muscles and obliterates the associated fat planes; and encasement or distortion of iliac vessels by the tumor.

Stage IVA CT findings

CT features of tumor extension into the bladder or rectum (stage IVA) include the following: focal obliteration of the perivesical or perirectal fat; eccentric or asymmetrical wall thickening that can be uniform, nodular, or serrated (see the image below); intraluminal extension of a soft-tissue mass; and a vesicovaginal fistula.

This CT image demonstrates a cervical tumor directly extending into the posterior wall of the bladder and into the left pelvic sidewall. Extension into the pelvic sidewall is a feature of stage IIIB disease, whereas involvement of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease.

This CT image demonstrates a cervical tumor directly extending into the posterior wall of the bladder and into the left pelvic sidewall. Extension into the pelvic sidewall is a feature of stage IIIB disease, whereas involvement of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease.

Stage IVB CT findings

The CT finding of enlarged inguinal and/or retroperitoneal lymph nodes is considered a feature of stage IVB (see the images below).

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma. This image of the mid abdomen shows borderline enlarged lymph node in the left para-aortic region, presumably secondary to metastasis, which is consistent with stage IVB disease. Multiple findings are visualized in this patient in other anatomic regions (please see the images below included in Stage IVB CT findings).

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma. This image of the mid abdomen shows borderline enlarged lymph node in the left para-aortic region, presumably secondary to metastasis, which is consistent with stage IVB disease. Multiple findings are visualized in this patient in other anatomic regions (please see the images below included in Stage IVB CT findings).

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The image at the kidneys level shows left hydronephrosis which is a feature of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The image at the kidneys level shows left hydronephrosis which is a feature of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

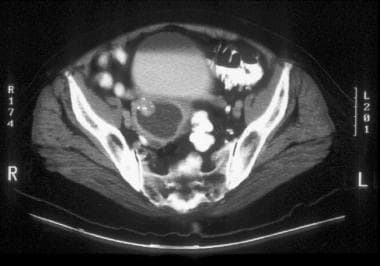

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). This image of the mid pelvis shows cervical tumor extending into the upper uterus, borderline enlarged lymph nodes, presumably secondary to metastasis, and left hydroureter. The pelvic lymph node enlargement and left hydroureter are features of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). This image of the mid pelvis shows cervical tumor extending into the upper uterus, borderline enlarged lymph nodes, presumably secondary to metastasis, and left hydroureter. The pelvic lymph node enlargement and left hydroureter are features of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

Staging limitations of CT

The pitfalls and limitations of CT in staging cervical cancer include the following:

-

Understaging of cancers with microscopic tumor spread.

-

Overlap with the appearances of other malignant cervical or uterine masses and leiomyomata.

-

Misinterpreting normal parametrial vessels and/or uterine ligaments as evidence of parametrial tumor invasion.

-

Similarity in the appearances of the irregular cervical margins and adjacent soft-tissue stranding due to parametrial tumor invasion and due to parametritis that is secondary to surgical biopsy, cervical conization, uterine curettage, or infection of the primary tumor.

-

Inability to exclude metastasis in normal-sized lymph nodes.

-

Inability to differentiate lymph node enlargement due to metastasis from that which results from benign causes.

-

Difficulty in definitively detecting tumor extension to the bladder or rectal mucosa.

Degree of confidence

Clinical staging by experienced gynecologic oncologists is more accurate than CT scanning in evaluating patients with stage IB or IIA tumors. CT is not recommended for the routine staging of early cervical cancer, and the value of this modality is also limited in the assessment of parametrial tumor invasion (stage IIB tumors), with an accuracy in the range of 30-76%.

The accuracy of CT increases in the setting of advanced disease, reportedly as high as 92% in evaluating patients with stage IIIB-IVB disease. The accuracy of CT in the detection of enlarged lymph nodes secondary to metastasis is about 65-80% in the pelvis and about 80-98% in the abdominal retroperitoneum. However, the accuracy of CT in the overall staging of cervical cancer is reportedly about 58-88%.

CT is therefore most valuable (1) in evaluating patients with advanced disease that has progressed beyond the uterus (stage IIB or worse), (2) in detecting enlarged lymph nodes and in guiding biopsy of those nodes, and (3) in depicting urinary tract involvement (obviating the need for IVU).

Note that CT is not consistently reliable for evaluating tumor size, and it is not sufficiently accurate for detecting early invasion of the parametrium, vagina, bladder, or rectum. Vaginal extension of cervical carcinoma is best evaluated with the use of clinical methods.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Exquisite high-resolution images of the female pelvis can be obtained by using current state-of-the-art MRI technology, including high–field-strength systems with torso phased-array coils or specialized endorectal or endovaginal coils. However, published reports indicate that the strength of the magnetic field and the type of coil used have no significant impact on the accuracy of MRI in detecting or evaluating the size of the primary cervical tumor, in depicting the locoregional extent of the tumor, or in staging the overall disease process. [35, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]

The routine use of high-resolution, sagittal and axial, T2-weighted, fast spin-echo (FSE) sequences and axial, T1-weighted, spoiled gradient-echo sequences is advocated. The sagittal, T2-weighted images facilitate the evaluation of the primary cervical tumor and of the tumoral extension into the uterine corpus, vagina, bladder, or rectum. The axial images are critical for evaluating the extent of stromal penetration and for detecting parametrial invasion.

The administration of an antiperistaltic agent, such as glucagon, may be useful in diminishing internal motion artifacts.

The value and role of intravenous contrast material in the MRI staging of cervical cancer are controversial. Additional investigative studies are needed to determine the appropriate indications and optimal techniques for contrast-enhanced imaging.

MRI Appearance of normal cervix

The anatomic details of the normal cervix are best depicted on T2-weighted images. [46] The epithelium and the mucus in the endocervical canal appear together as a spindle-shaped central zone with a high signal intensity that is similar to that of the endometrium. The surrounding cervical stroma is depicted as a relatively wide band with a predominantly low signal intensity, which likely reflects the overall preponderance of fibrous tissue. The outermost cervical stroma is depicted as a thin layer of intermediate signal intensity, which likely reflects the predominance of smooth muscle in this region of the stroma.

High-resolution, T2-weighted images obtained with specialized coils may allow visualization of the mucosal plicae palmatae as a feathery layer of intermediate signal intensity interposed between the central high signal intensity of the endocervical region and the low signal intensity of the stroma. On T1-weighted images and proton-density–weighted images, the normal cervix has a homogeneous intermediate to low signal intensity; however, the above-described internal anatomic details are not discernible.

T2-weighted images depict the vaginal mucosa with a high signal intensity and the vaginal wall with an intermediate signal intensity. T1-weighted images and proton-density–weighted images depict the vaginal mucosa and wall as a single structure with a homogeneous, intermediate to low signal intensity. The intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast material usually causes greater enhancement of the cervical and vaginal mucosa and the outermost cervical stromal layer than of the predominantly fibrous cervical stroma or the vaginal wall. [47] Parametrial enhancement also occurs.

MRI appearance of cervical carcinoma

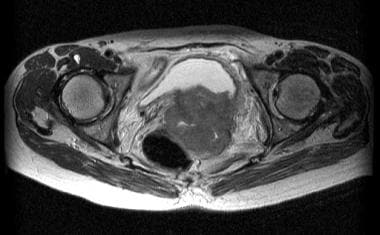

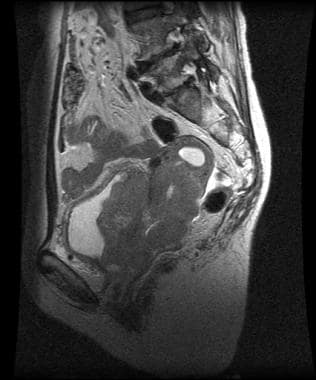

Cervical carcinoma has a long T1 and a long T2 that render this disease relatively hyperintense on proton-density–weighted and T2-weighted images (see the images below), in which the signal intensity of the tumor is approximately similar to that of the endometrium. The hyperintense appearance on T2-weighted images accounts for the essentially consistent conspicuity of the primary tumor against the background of the hypointense normal cervical stroma.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion. This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe, extending anteriorly through the disrupted vaginal fornix, and involving the parametrium. The endometrial cavity is distended by fluid. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion. This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe, extending anteriorly through the disrupted vaginal fornix, and involving the parametrium. The endometrial cavity is distended by fluid. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe and protruding beyond the cervical margin into the parametrium. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe and protruding beyond the cervical margin into the parametrium. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

The tumor has a medium signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Cervical carcinoma exhibits variable contrast enhancement after the intravenous administration of gadolinium chelates. Some tumors may even lose their conspicuity as they become isointense with the surrounding, contrast-enhanced stroma.

Direct visualization of the primary cervical neoplasm allows MRI to be reliable in assessing the size of the tumor and the extent of stromal invasion or penetration. Partial stromal invasion is characterized by the presence of an intact layer of low–signal-intensity stroma at the periphery of the cervix, which is visualized on T2-weighted images as a dark stripe or ring that surrounds the hyperintense tumor; this finding virtually excludes tumor spread into the parametrium.

Full-thickness stromal invasion is typically depicted on T2-weighted images as disruption of the hypointense or dark-appearing stromal stripe by an abnormal, high–signal-intensity tumor, which extends through the entire stromal depth to the outer cervical margin (see the image below). However, the finding of full-thickness stromal invasion by itself should not be considered evidence of tumor spread beyond the cervix, although direct microscopic invasion of the parametrium or vagina is possible in this setting.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor with full-thickness stromal invasion causing complete loss of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring. Also depicted is invasion of the parametrium and the posterior bladder wall; this finding is indicative of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor with full-thickness stromal invasion causing complete loss of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring. Also depicted is invasion of the parametrium and the posterior bladder wall; this finding is indicative of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or MRA scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Stage I MRI findings

MRI manifestations of invasive cancer confined to the cervix (stage I) include the following (see also the images below):

-

Normal MRI appearance of the cervix.

-

Intact layer or ring of hypointense cervical stroma that completely surrounds the hyperintense tumor on T2-weighted images.

-

Full-thickness disruption of the hypointense cervical stroma by a high–signal-intensity tumor, with preservation of the normal morphology and signal intensity of the parametrium and vagina.

-

Smooth, well-defined, and intact peripheral cervical contours.

-

Lack of parametrial soft-tissue strands or masses.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer. This image shows a circumscribed, hyperintense mass in the posterior lip of the cervix that is associated with intact peripheral cervical margins and an intact parametrium. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer. This image shows a circumscribed, hyperintense mass in the posterior lip of the cervix that is associated with intact peripheral cervical margins and an intact parametrium. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a hyperintense tumor in the posterior lip of the cervix. There is segmental disappearance of the right lateral and posterior aspects of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring, which is consistent with localized, deep stromal invasion. However, the tumor is fairly sharply marginated and does not protrude beyond the stromal ring, and the parametrium is intact. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a hyperintense tumor in the posterior lip of the cervix. There is segmental disappearance of the right lateral and posterior aspects of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring, which is consistent with localized, deep stromal invasion. However, the tumor is fairly sharply marginated and does not protrude beyond the stromal ring, and the parametrium is intact. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Stage IIA MRI findings

In stage IIA, the tumor spread into the vagina may be depicted as a high-signal–intensity mass that disrupts or replaces the hypointense vaginal wall, as a segmental disruption of the low signal intensity of the vaginal wall, or as a thickened hyperintense vagina.

Difficulties with interpretation are encountered in determining the presence or absence of minimal vaginal invasion. Overstaging errors are caused by relatively large, exophytic tumors that expand the vaginal fornix and stretch the vaginal wall without invading it. In this setting, the stretched and thin vaginal fornix may not be recognized as intact, even though it is not disrupted by tumor.

Vaginal extension of cervical carcinoma can be reliably evaluated by clinical methods, and therefore, the role of MRI is not crucial in this regard.

Stage IIB MRI findings

The MRI features of parametrial tumor invasion (stage IIB) include the following, in order of increasing PPV:

-

Loss of definition, irregularity, or nodularity of the cervical contours.

-

Prominent or thick soft-tissue strands in the parametrial fat.

-

Full-thickness stromal invasion accompanied by irregularity in the interface between the tumor and the parametrium, asymmetrical tumor protrusion, or encasement of parametrial vessels.

-

Full-thickness stromal invasion with direct extension of abnormal signal intensity or mass into the parametrium.

In addition to tumor extension beyond the cervix, the surrounding thin vaginal fornix should be disrupted before parametrial invasion is suspected in patients with tumors arising in the vaginal portion of the cervix.

Stage IIIB MRI findings

The MRI features of pelvic sidewall tumor invasion (stage IIIB) include the following:

-

Parametrial tumor that extends beyond the lateral margins of the cardinal ligament or within 2-3 mm from the pelvic sidewall.

-

Confluent soft tissues or irregular, thick, soft-tissue strands that extend through the parametrium to the obturator internus muscle or piriformis muscle.

-

Loss of the normal low signal intensity of the pelvic sidewall muscle that is adjacent to the tumor.

-

A confluent mass that incorporates the pelvic sidewall muscles and obliterates the associated fat planes.

-

Encasement or distortion of the iliac vessels by the tumor.

The evaluation of lymph nodes is based on morphologic size criteria. Pelvic lymph nodes larger than 1.0 cm in their short axis are considered enlarged. The detection of enlarged pelvic lymph nodes on MRI is considered to be equivalent to pelvic sidewall tumor extension.

The occasional detection of intranodal necrosis is most consistent with metastasis and is best depicted on contrast-enhanced images.

Stage IVA MRI findings

MRI features of tumor extension into the bladder or rectum (stage IVA) include the following (see also the image below):

-

Focal obliteration of the perivesical or perirectal fat.

-

Segmental disruption of the low signal intensity of the bladder or rectal wall that is adjacent to tumor.

-

Intraluminal extension of a soft-tissue mass.

-

Eccentric or asymmetrical wall thickening that can be uniform, nodular, or serrated.

With regard to the last item above, the normal low signal intensity of the bladder or rectal wall is replaced by an abnormally high signal intensity.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor extending through the entire cervical stroma and extensively involving the uterine corpus, vagina, bladder wall, and posterior urethral region. The invasion of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor extending through the entire cervical stroma and extensively involving the uterine corpus, vagina, bladder wall, and posterior urethral region. The invasion of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

Stage IVB MRI findings

The MRI finding of enlarged inguinal and/or retroperitoneal lymph nodes is considered a feature of stage IVB. In some patients, treatment planning may require CT–guided FNA biopsy of lymph nodes that appear enlarged on MRI.

Staging limitations of MRI

MRI has limitations related to evaluating morphologic alterations in the organs or anatomic regions that may be involved by tumor spread, which are similar to the CT limitations listed in the section of CT staging (see Staging limitations of CT). Additional pitfalls pertinent to MRI staging of cervical cancer include the following:

-

The high SI of a cervical lesion on T2-weighted images is not specific for carcinoma; cervical leiomyoma, postbiopsy changes, nabothian cysts, and inflammatory disease may have a similar hyperintense pattern.

-

False-positive findings due to hyperintense edema and inflammatory changes, surrounding the primary tumor or present in the adjacent organs, lead to overestimation of the size of the tumor or overstaging of the extent of tumor.

-

Difficulty in visualizing or depicting the remaining normal cervical stromal stripe and the normal vaginal fornix that are stretched thin by relatively large tumor confined in the cervix.

-

Difficulty in assessing the status of the parametrium or vagina in the setting of full-thickness invasion of cervical stroma, particularly when a bulky tumor is present.

Degree of confidence

The overall accuracy of MRI staging is reported to be 76-92%. MRI is most valuable in the direct visualization of the primary cervical tumor and in the evaluation of locoregional tumor extent. Hricak and Yu reported diagnostic performance statistics based on compiled data they obtained from several published studies. In the evaluation of parametrial invasion, MRI had an overall accuracy of 90%, a positive predictive value of 67%, and a negative predictive value of 95%; in the detection of lymph node metastasis, the values were 88%, 66%, and 90%, respectively. [25, 48]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography (US) has been used to evaluate the size and locoregional extent of the tumor. In the early stage of cervical carcinoma, the primary lesion is difficult to depict with any imaging modality, including transvaginal US and transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS).

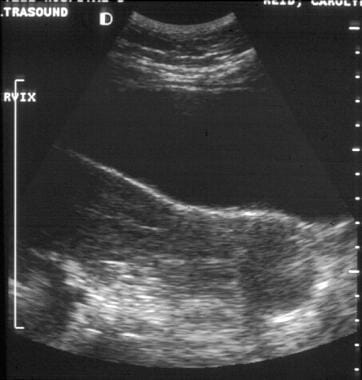

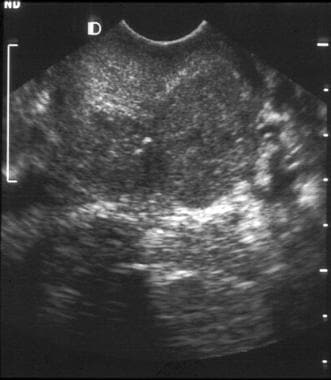

Eventually, with disease progression, the tumor mass may appear as a hypoechoic or isoechoic region with undefined margins, or the disease may be manifested as an enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity (see the images below). In general, the intracervical cancer is not clearly distinguished from the surrounding normal cervical stroma.

Sagittal transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

Sagittal transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

Transverse transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

Transverse transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

In a minority of patients, the tumor may be depicted as a poorly outlined focal lesion (see the images below) that is readily distinguishable from the normal cervical stroma. The lesion may have a hypoechoic, hyperechoic, or mixed echogenicity appearance. Fluid can accumulate in the uterine cavity as a result of the tumor obstructing the endocervical canal.

This sagittal transabdominal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the posterior aspect of the cervix.

This sagittal transabdominal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the posterior aspect of the cervix.

This transverse transvaginal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the left posterior aspect of the cervix.

This transverse transvaginal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the left posterior aspect of the cervix.

This sagittal transvaginal color Doppler sonogram shows prominent vascular flow in the cervical tumor.

This sagittal transvaginal color Doppler sonogram shows prominent vascular flow in the cervical tumor.

Typical US features of a grossly infiltrated parametrium include irregular or nodular lateral margins of asymmetrically protruding tumors, parametrial vascular encasement, and replacement of the vascular parametrial connective tissue by parenchymatous tissue with echotexture characteristics that are identical to those of the primary intracervical cancer.

Tumor extension into the sidewall is suggested when the parametrial tumor is within 2-3 mm of the musculature. Advanced tumor may grossly involve the muscles at the pelvic sidewall, encase the iliac vessels, or directly extend into the bladder or rectal wall.

US has limitations in evaluating the tumor extent that are similar to the CT limitations discussed earlier. Additional limitations that are pertinent to the US staging of cervical cancer include the following:

-

Low-contrast resolution that causes difficulties in the direct visualization of the primary cervical tumor and in distinguishing the tumor from the adjacent normal tissues of the cervical stroma, uterine corpus, parametrium, or vagina.

-

Overstaging because of overlap in the appearance of the tumor invasion and that of any coexisting intrapelvic pathology, such as endometriosis and inflammatory changes.

-

Inability to adequately visualize all the anatomic regions in the pelvis or the areas containing lymph nodes.

-

Inability to image all the potential sites of metastasis.

Nuclear Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) with use of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) has some value relative to conventional imaging methods for (1) the detection of nodal metastatic disease and recurrent cervical cancer, (2) possibly being effective in the evaluation of cases of locally advanced cervical cancer in which CT findings are negative or equivocal, and (3) possibly being predictive of survival outcome. [33, 49, 50, 51, 52]

Reinhardt et al found a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 100% for FDG-PET scanning in nodal staging compared with a 73% sensitivity and 83% specificity for MRI. [52]

Belhocine et al found that PET scanning was most valuable in staging extrapelvic metastases and in detecting recurrence, whereas MRI was most valuable in evaluating the locoregional status of the disease. [51] PET scan staging significantly influenced management in 18% of the authors' cases.

Although a positive FDG-PET study may obviate nodal sampling in patients with positive nodes, FDG-PET scanning does not depict microscopic nodal disease and cannot replace invasive procedures if microscopic disease might be clinically relevant. [53]

For pelvic malignancies, urinary FDG activity can be a confounding factor, and a Foley catheter and diuretics should be used, if possible, to minimize urinary activity.

-

CT of clinically visible carcinoma confined to the cervix (stage IB). The image shows a mass with slightly heterogeneous attenuation that expands the cervix and is surrounded by a thin rim of relatively preserved stroma. The cervical margins are smooth, well defined, and intact. Parametrial soft-tissue stranding or masses are lacking, and the periureteral fat planes are preserved.

-

CT image through the upper uterus shows fluid that markedly distends the endometrial cavity secondary to obstruction of the endocervical canal by cervical cancer. A small submucosal leiomyoma projects into the right anterior aspect of the endometrial cavity and has minute calcifications.

-

CT of a large, lobulated mass that is replacing the cervix and showing nonuniform hypoattenuation. The air and fluid in the center of the mass are consistent with tumor necrosis and a complicating infection (the patient had purulent discharge). The central hypoattenuation in the uterine corpus is suggestive of minimal fluid in the cavity.

-

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated.

-

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by increased attenuation and prominent soft-tissue stranding in the parametrial fat. Parametritis can result in similar findings. The cervix shows ill-defined hypoattenuation, but the tumor is not clearly delineated. In addition, a subserosal leiomyoma protrudes from the left side of the uterus.

-

Sagittal transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

-

Transverse transabdominal sonogram of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a diffusely enlarged cervix with heterogeneous echogenicity. The tumor margins are not clearly delineated, and the parametrial invasion is not obvious.

-

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. This image shows a hypoattenuating tumor occupying the entire cervix and extending to the outer posterior and right cervical margins. This finding is consistent with full-thickness stromal invasion. Minimal air in the center is related to the biopsy. A vaginal tampon is present to the right of the cervix.

-

CT of clinical stage IIB cervical carcinoma. Parametrial invasion is depicted with CT as loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by soft-tissue attenuation that replaces the periureteral fat on the right.

-

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right and extends into the anterior and right-sided rectal walls.

-

CT of parametrial and rectal invasion by cervical carcinoma. There is loss of definition of the cervical contours, accompanied by mass-like soft tissue which replaces the parametrial fat on the right side. The cervix is diffusely enlarged and shows subtle hypoattenuation, but the tumor margins are not clearly delineated.

-

This CT image demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node at the left pelvic sidewall, a finding that is consistent with pelvic lymph node metastasis, which is indicative of stage IIIB disease. The cystic consistency is not unusual for metastatic cervical carcinoma. The primary tumor is well depicted as a hypoattenuating, circumscribed mass. A cyst is present in the anteriorly located left ovary.

-

This CT image demonstrates a cervical tumor directly extending into the posterior wall of the bladder and into the left pelvic sidewall. Extension into the pelvic sidewall is a feature of stage IIIB disease, whereas involvement of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease.

-

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma. This image of the mid abdomen shows borderline enlarged lymph node in the left para-aortic region, presumably secondary to metastasis, which is consistent with stage IVB disease. Multiple findings are visualized in this patient in other anatomic regions (please see the images below included in Stage IVB CT findings).

-

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). The image at the kidneys level shows left hydronephrosis which is a feature of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

-

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). This image of the mid pelvis shows cervical tumor extending into the upper uterus, borderline enlarged lymph nodes, presumably secondary to metastasis, and left hydroureter. The pelvic lymph node enlargement and left hydroureter are features of stage IIIB disease. The findings of stage IV disease in this patient are depicted on the other images.

-

CT of a patient with stage IVB cervical carcinoma (same patient as in the previous image). This image of the lower pelvis shows direct intraluminal extension of a large cervical tumor into the bladder, which is a feature of stage IVA disease. However, the images of the abdomen showed borderline enlarged left para-aortic lymph node consistent with stage IVB disease.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer. This image shows a circumscribed, hyperintense mass in the posterior lip of the cervix that is associated with intact peripheral cervical margins and an intact parametrium. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IB cervical cancer (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a hyperintense tumor in the posterior lip of the cervix. There is segmental disappearance of the right lateral and posterior aspects of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring, which is consistent with localized, deep stromal invasion. However, the tumor is fairly sharply marginated and does not protrude beyond the stromal ring, and the parametrium is intact. These are features of cancer that is confined to the cervix (stage IB). Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion. This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe, extending anteriorly through the disrupted vaginal fornix, and involving the parametrium. The endometrial cavity is distended by fluid. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of stage IIB cervical cancer with parametrial and anterior vaginal fornix invasion (same patient as in the previous image). This image shows a slightly hyperintense cervical tumor disrupting the hypointense stromal stripe and protruding beyond the cervical margin into the parametrium. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor extending through the entire cervical stroma and extensively involving the uterine corpus, vagina, bladder wall, and posterior urethral region. The invasion of the bladder wall is a feature of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of a large cervical tumor with full-thickness stromal invasion causing complete loss of the hypointense stromal stripe or ring. Also depicted is invasion of the parametrium and the posterior bladder wall; this finding is indicative of stage IVA disease. Courtesy of Kaori Togashi, MD, Hitachi Medical Corporation, Chair of Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imageology, Kyoto University, Japan.

-

This sagittal transabdominal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the posterior aspect of the cervix.

-

This transverse transvaginal sonogram shows a circumscribed hypoechoic tumor in the left posterior aspect of the cervix.

-

This sagittal transvaginal color Doppler sonogram shows prominent vascular flow in the cervical tumor.