Practice Essentials

Restrictive cardiomyopathy, or restrictive cardiac disease, is defined as abnormal diastolic function in association with relatively well-preserved systolic function (at least in the early stages of the disease). Clinically, restrictive cardiomyopathy is difficult to distinguish from constrictive pericarditis, which is treatable. In 1981, Shabetai proposed a working definition of restrictive cardiomyopathy: "an idiopathic or systemic disease of the ventricular chambers that produces a clinical and hemodynamic picture that strongly simulates constrictive pericarditis." [1]

Three of the leading causes of RCM are cardiac amyloidosis, cardiac sarcoidosis, and cardiac hemochromatosis. [2, 3, 4]

Although patients with idiopathic heart disease present with restrictive cardiomyopathy, the term restrictive cardiomyopathy usually refers to a group of primary or secondary infiltrative disorders involving the myocardium in which the heart chambers are unable to fill properly and cannot pump blood efficiently. The decreased heart function affects the lungs, liver, and other body systems.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is rare in the United States and most other industrialized nations. In general, restrictive cardiomyopathy does not appear to be inherited; however, some of the diseases that lead to the condition are transmitted genetically.

Diagnostic tests include ECG, echocardiography, coronary angiography, chest radiography, CT, and MRI. [5]

Diagnostic criteria include the absence of cardiomegaly on chest radiographs, although findings consistent with pulmonary venous hypertension may be seen. On echocardiography, ventricular walls appear normal or symmetrically thickened; the hallmark is rapid early diastolic filling and slow late diastolic filling with normal or slightly reduced ventricular volume and systolic function.

On cardiac catheterization, the ventricular end-diastolic pressure is elevated, with a dip-and-plateau configuration of the diastolic portion of the ventricular pressure pulse. The ejection fraction is normal to slightly decreased, and X and Y descent are prominent.

(See the images of restrictive cardiomyopathy below.)

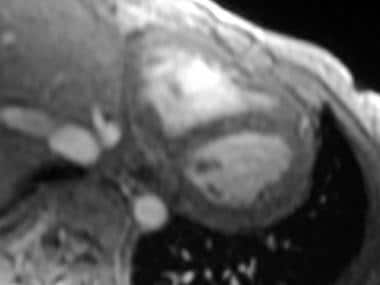

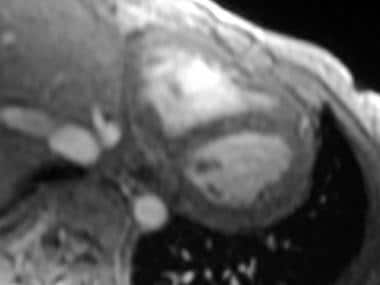

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial double inversion-recovery MRI of the heart in a 30-year-old woman with sarcoid demonstrates a normal pericardium.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial double inversion-recovery MRI of the heart in a 30-year-old woman with sarcoid demonstrates a normal pericardium.

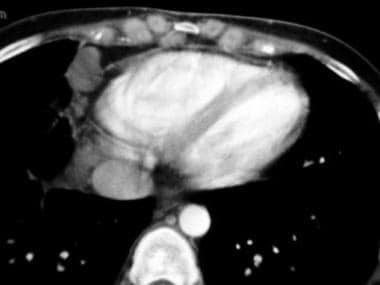

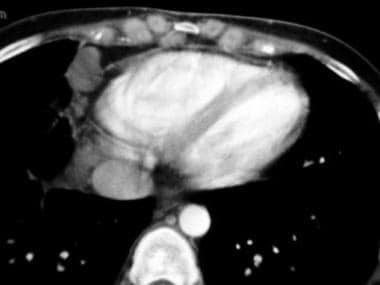

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the heart (same patient as in previous image) shows a thin pericardium without calcification. Note the cardiophrenic and internal mammary lymph nodes. The patient had extensive mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, as well as interstitial lung changes.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the heart (same patient as in previous image) shows a thin pericardium without calcification. Note the cardiophrenic and internal mammary lymph nodes. The patient had extensive mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, as well as interstitial lung changes.

Imaging modalities

Echocardiography is the primary imaging modality for restrictive cardiomyopathy. Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography can determine diastolic dysfunction and distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from restrictive physiology due to constrictive pericarditis. [2]

Echocardiography alone is not definitive because the hemodynamic properties of restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis are similar, and pericardial thickness may be evaluated incompletely. Echocardiography may be limited by inadequate echo-lucent windows, and important clues of pericardial thickness may be missed because of near-field and far-field effects.

Echocardiographic findings that support a diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis include thickened valves and pericardial effusion. [3]

Cardiac echocardiographic techniques include speckle tracking, which can assess ventricular function in early myocardial disease. Speckles are groups of myocardial pixels with particular gray-scale characteristics. A speckle is defined as the spatial distribution of gray values. [2, 4]

Cardiac MRI can also help make the diagnosis of restrictive cardiomyopathy. [2] MRI, which is primarily employed in pericardial examination, has high sensitivity, specificity, and predictive accuracy (88%, 100%, and 93%, respectively) in differentiating restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis. [5] MRI is poor in identifying calcification. [6, 7, 8]

CT is similar to MRI in its ability to assess pericardial thickness; CT is better able to detect pericardial calcification. MRI, CT, and echocardiography may also demonstrate early termination of left ventricular filling. CT involves ionizing radiation, and many systems do not enable a dynamic evaluation of filling.

Differential diagnosis

Restrictive cardiomyopathy may be difficult to differentiate from constrictive pericarditis. MRI is a useful noninvasive diagnostic tool because it clearly demonstrates the thickness of the pericardium and because it may provide additional information to aid in the diagnosis of some of the infiltrative conditions that cause restrictive heart disease. [9]

In the evaluation of constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy, advanced imaging techniques such as CT and MRI play a crucial role in diagnosis. In as many as 50% of patients with constrictive pericarditis, calcification of the pericardium does not occur. A slightly thickened pericardium may be demonstrated in some patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy. Analysis of a myocardial biopsy specimen may be necessary to make the diagnosis.

Endomyocardial biopsy may be used to confirm the diagnosis. In some patients, surgical exploration is the only means by which to definitely distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis, although a systematic search for the correct diagnosis often obviates exploratory thoracotomy or sternotomy.

Findings of hyperkinetic ventricular free wall and ventricular hypertrophy are characteristic of hypertrophic cardiomyopathies.

Radiography

For patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy, conventional chest radiographs may demonstrate the typical appearance of congestive heart failure but without cardiomegaly. Plain images may be normal, showing neither cardiomegaly nor congestive heart failure.

Conventional radiographs are used in conjunction with echocardiography and MRI findings. Chest radiograph findings are not definitive in the evaluation of restrictive cardiac disease, particularly when there is clinical concern as to whether the patient has constrictive pericarditis or restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Computed Tomography

CT is not especially useful in the evaluation of restrictive cardiomyopathy. However, given appropriate hemodynamics, pericardial calcification may indicate pericardial constriction; such a finding may thus exclude the diagnosis of restriction.

Although calcification of the pericardium is associated with constrictive pericarditis, not with restrictive cardiomyopathy, the absence of calcium is not a diagnostic discriminator. In 50% of cases of constrictive pericarditis, there are no findings of a calcified pericardium; however, although a thickened pericardium (>4 mm) is associated with constrictive pericarditis, some patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy have a mildly thickened pericardium in the absence of calcification (see the image below). Advanced imaging techniques may not be sufficient to make the diagnosis of restrictive cardiomyopathy, necessitating myocardial biopsy.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the heart (same patient as in previous image) shows a thin pericardium without calcification. Note the cardiophrenic and internal mammary lymph nodes. The patient had extensive mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, as well as interstitial lung changes.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the heart (same patient as in previous image) shows a thin pericardium without calcification. Note the cardiophrenic and internal mammary lymph nodes. The patient had extensive mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, as well as interstitial lung changes.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is a sophisticated, accurate, noninvasive tool that is well suited to the evaluation of the morphology and function of the heart. In restrictive cardiomyopathy, the thickness of the pericardium (< 4 mm) is a key finding (see the image below). [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17] A diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis (excluding restrictive cardiomyopathy) may be made on the basis of pericardial thickness. The sensitivity is 88%, specificity 100%, and accuracy 93%.

Ventricular hypertrophy is not associated with restrictive cardiomyopathy, but some degree of thickening may be seen on both cross-sectional imaging and echocardiography in cases of infiltrative restrictive cardiac disease (eg, amyloidosis or hemochromatosis).

Patients with a history of cardiac surgery or pericardiotomy may have a thickened pericardium without a constrictive physiologic pattern. Conversely, in the postoperative patient, the visceral pericardium may constrict the heart without being abnormally thick.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial double inversion-recovery MRI of the heart in a 30-year-old woman with sarcoid demonstrates a normal pericardium.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial double inversion-recovery MRI of the heart in a 30-year-old woman with sarcoid demonstrates a normal pericardium.

Ultrasonography

Echocardiography is the primary imaging modality for restrictive cardiomyopathy. Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography can determine diastolic dysfunction and distinguish restrictive cardiomyopathy from restrictive physiology due to constrictive pericarditis. [2, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22] Normal ventricular size and systolic function usually are evident in cases of restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Echocardiography alone is not definitive because the hemodynamic properties of restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis are similar, and pericardial thickness may be evaluated incompletely. Echocardiography may be limited by inadequate echo-lucent windows, and important clues of pericardial thickness may be missed because of near-field and far-field effects.

Echocardiographic findings that support a diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis include thickened valves and pericardial effusion. [3]

Cardiac echocardiographic techniques include speckle tracking, which can assess ventricular function in early myocardial disease. Speckles are groups of myocardial pixels with particular gray-scale characteristics. A speckle is defined as the spatial distribution of gray values. [2, 4]

Findings that have been described as helpful in diagnosing restrictive cardiomyopathy include mid-diastolic reversal of flow across the mitral and tricuspid valves. Atrial enlargement with normal left ventricular end-diastolic dimensions may also be seen.

Typically, patients with constrictive pericarditis have a thickened pericardium and marked respiratory variation during diastole. One study showed that Doppler myocardial velocity gradients, as measured from the left ventricular posterior wall during the predetermined phases of the cardiac cycle, are lower in patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy than in patients with constrictive pericarditis. [19]

Restrictive cardiomyopathy might not be distinguishable from constrictive pericarditis on the basis of echocardiography alone. Echocardiography may be limited by inadequate echo-lucent windows, and it may not be sufficient for the evaluation of pericardial thickness. In such cases, use of CT or MRI is the next step.

-

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial double inversion-recovery MRI of the heart in a 30-year-old woman with sarcoid demonstrates a normal pericardium.

-

Restrictive cardiomyopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the heart (same patient as in previous image) shows a thin pericardium without calcification. Note the cardiophrenic and internal mammary lymph nodes. The patient had extensive mediastinal and hilar adenopathy, as well as interstitial lung changes.