Practice Essentials

Gastrointestinal carcinoid, also called carcinoid tumor, is the most common primary tumor of the small bowel and appendix. Gastrointestinal carcinoid accounts for more than 95% of all carcinoids. The tumors arise from enterochromaffin cells of Kulchitsky, which are considered neural crest cells situated at the base of the crypts of Lieberkuhn. Gastrointestinal carcinoids account for 1.5% of all gastrointestinal tumors. The tumors elaborate serotonin and other histaminelike substances that normally are transported to the liver, where they are metabolized. [1] Most tumors of the gastrointestinal tract are located in the small bowel. Prevalence of rectal carcinoids has been increasing as a result of increased colorectal screening. [2, 3, 4, 5]

Carcinoid tumors are of neuroendocrine origin and derived from primitive stem cells in the gut wall, especially the appendix. They can be seen in other organs, including the lungs,mediastinum, thymus,liver, bile ducts,pancreas,bronchus,ovaries, prostate,and kidneys. Although carcinoid tumors have a tendency to grow slowly, they do have the potential for metastasis.Carcinoid tumors are divided into well-differentiated (ie, low grade and intermediate grade) and poorly differentiated (ie, high grade). Classification is based on the extent of the tumor: local, regional, and distant spread. [1, 6, 7]

Carcinoid tumors account for 13-34% of small bowel tumors and 17-46% of malignant tumors of the small bowel. Neuroendocrine tumors have an incidence of 40-50 cases per million. [1]

One classification of carcinoid tumors is based on location from which the tumor cells arise and the vascular supply: foregut, midgut, hindgut. The foregut includes tumors arising from the lungs, stomach, liver, biliary tract, pancreas, and first portion of the duodenum. The midgut includes the distal duodenum, the small intestines, the appendix, the right colon, and the proximal transverse colon. The hindgut includes the distal transverse colon, the left colon, and the rectum. [8, 4, 5]

(Characteristics of gastrointestinal cancer are shown in the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of small-bowel carcinoid. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Small-bowel dilatation is confined to the upper abdomen. Speckled calcification is noted in a small, circular mass to the right of the mid lumbar spine.

Characteristic appearance of small-bowel carcinoid. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Small-bowel dilatation is confined to the upper abdomen. Speckled calcification is noted in a small, circular mass to the right of the mid lumbar spine.

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. A 10-mm lower CT section shows stellate radiating and beaded mesenteric neurovascular bundles of the mesentery (arrows) associated with kinking (K) of the small bowel.

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. A 10-mm lower CT section shows stellate radiating and beaded mesenteric neurovascular bundles of the mesentery (arrows) associated with kinking (K) of the small bowel.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the next image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the next image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the previous image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the previous image for a left-sided image).

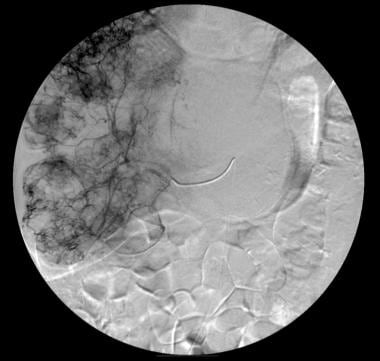

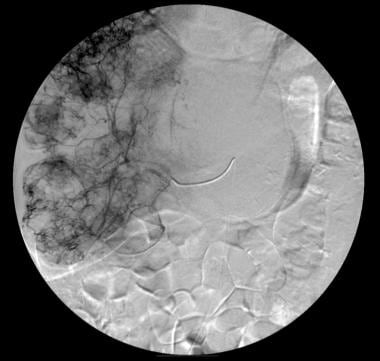

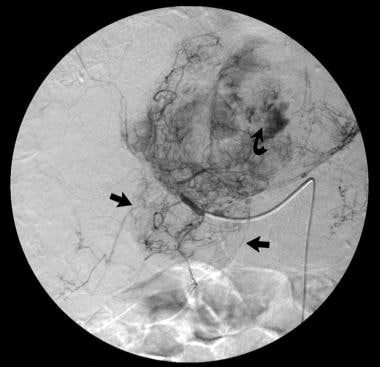

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Right hepatic angiogram shows early enhancement of multiple liver tumors.

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Right hepatic angiogram shows early enhancement of multiple liver tumors.

Most tumors are clinically silent, but they may cause pain or intestinal obstruction, weight loss, a palpable mass, or, rarely, bowel perforation. Carcinoid syndrome occurs when the humoral load exceeds the capacity of monoamine oxidase (MAO) present in the liver and lung to metabolize serotonin. Most patients with carcinoid syndrome have liver metastases from a bowel carcinoid, although in rare cases, the humoral load from a primary tumor may overwhelm the liver and the capacity of the lungs to metabolize serotonin. Rarer still is carcinoid syndrome that develops in patients with noncarcinoid malignant tumors and dermatomyositis.

Imaging modalities

A carcinoid is a functioning tumor, which means that clinical correlation is important. Indications for performing various imaging studies are dependent on the initial presentation. Two techniques stand out: CT scanning is better at providing anatomic information than are barium studies, and radionuclide studies add a functional element, which is obviously important in the context of carcinoid syndrome. None of the radiologic techniques can provide a specific diagnosis; therefore, clinical input is of utmost importance. [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14]

Diagnosis is usually achieved by using several complementary imaging techniques.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy [9, 15, 16] can aid diagnosis by localizing primary and metastatic sites of gastroenteropancreatic endocrine tumors. The degree of radionuclide uptake is related to somatostatin receptor density. In gastrointestinal carcinoids, the concentration at the receptor sites is high (90%). Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy performed with indium-111 (111In) octreotide and 111In pentetreotide is used to image many neuroendocrine tumors, including carcinoids with somatostatin-binding sites. [15]

Plain radiographic findings (eg, soft-tissue mass, punctate calcification within a mass, signs of intestinal obstruction) are not specific for carcinoids. Plain radiographs are usually obtained in an acute setting, being taken, for example, in patients presenting with intestinal obstruction or perforation.

Results of barium studies are nonspecific, and these tests are usually performed in patients presenting with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms. Clinical correlation is required. However, on a small-bowel barium series, kinking of the small-bowel loops is considered the hallmark of a small-bowel carcinoid tumor.

Ultrasonography is performed to investigate a variety of abdominal complaints. The radiologist must be aware of the ultrasonographic appearances of a carcinoid. Although these are nonspecific, they may lead to the most appropriate investigation and result in a diagnosis.

Computed tomography (CT) scan findings in a malignant carcinoid depend on its size, degree of mesenteric invasion and desmoplastic reaction, and the presence of regional lymph node invasion. In the appropriate setting, the appearance of a malignant carcinoid on a CT scan may be highly suggestive of a diagnosis of carcinoid.

Wang et al studied the CT enhancement patterns of 44 patients with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas, as confirmed by clinical pathology and immunohistochemistry. Most cases (81.8%) demonstrated moderately or obviously homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phases, with only 17.2% of cases appearing as heterogeneous enhancement. In addition, 86.4% of cases were further enhanced in the venous phase. The CT images also revealed some of the metastases, with some liver metastasis having obvious homogeneous enhancement. The authors concluded that the CT features of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinomas increase diagnostic accuracy, particularly enhancement patterns. [10]

Angiography is essential in interventional procedures involving liver metastases.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy and endoscopic ultrasonography have a direct clinical impact, because they influence individual therapeutic strategies.

In a study of 24 patients with gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors, endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, and CT were the primary diagnostic approaches. Mean age at presentation was 50 years (range, 7-74 yr), 14 patients were male, and 10 were female. The mean lesion was 8.3 mm (range, 2-20 mm), with 50% being type 1; 12.5% type 2; 29% type 3; and 8.3% type 4. [17]

Radiography

Plain radiographic findings of gastrointestinal carcinoids are nonspecific and may simply reflect bowel obstruction. Any cause of intestinal obstruction may mimic obstruction resulting from a carcinoid; moreover, on barium series, an intraluminal filling defect found at any location within the bowel, whether benign or malignant, may appear similar to a gastrointestinal carcinoid. The calcification occasionally seen in a pancreatic or bowel carcinoid is nonspecific and has a varied differential diagnosis; however, kinking of the small bowel on a barium series is considered the hallmark of a small-bowel carcinoid.

Biliary carcinoid

Cholangiography shows a polypoid filling defect within the biliary tree or an infiltrating form in which duct stenosis is demonstrated.

Colon carcinoid

On barium examination, radiologic features are similar to those of adenocarcinoma and include a filling defect within the colon caused by a sessile polyp, circumferential narrowing (apple-core lesion) associated with mucosal destruction, loss of mucosal folds, and ulceration.

Imaging findings of a malignant carcinoid depend on its size, the degree of mesenteric invasion/desmoplastic reaction, and the presence of regional lymph node invasion. Bowel loops in the right iliac fossa separate; and external compression, asymmetric spiculated contour, and kinking of adjacent bowel are demonstrated.

The carcinoid tumor may not be visible because it is usually buried in the adjacent mass. A large-bowel barium series may show compression or infiltration of the cecum at the base of the appendix.

Duodenal carcinoid

On barium series, duodenal carcinoid tumors appear as intraluminal polypoid lesions or infiltrating lesions that cause an irregular stricture.

Gastric carcinoid

Imaging findings are nonspecific and depend on the type of tumor. On barium meal examination, the most common finding is a single, intramural, sharply demarcated defect that is usually 2-3 cm in diameter.

Tumors may be located anywhere in the stomach, although a fundal location is said to be rare. Features may mimic leiomyoma/leiomyosarcoma. Tumors may be ulcerated. Less commonly, tumors may appear as a large ulcer or polypoid mass.

In type I disease, multiple sessile polypoid lesions of varying sizes may be seen arising from the wall of the stomach. Atypical carcinoids may occur in which histology demonstrates a combination of carcinoid and adenocarcinoma. Atypical tumors have a tendency to ulcerate and show more aggressive behavior, with local tumor spread and lymph node metastasis. The prognosis in patients with atypical tumors is usually poor.

A bull's-eye, or target, lesion may be seen. This appears as an ulcer on the apex of a nodule on barium meal examination. When a target lesion is noted, the differential diagnosis includes gastric metastases (melanoma, lymphoma, carcinoma-breast, bronchus, pancreas), leiomyoma, pancreatic rest, and gastric neurofibroma.

Esophageal carcinoid

Esophageal carcinoid tumors may present as intraluminal, extramucosal filling defects on barium studies.

Pancreatic carcinoid

Plain radiographs of pancreatic carcinoid may show curvilinear calcification in the region of the pancreatic bed

Rectal carcinoid

Tumors are indistinguishable from the more common adenomatous polyps on barium enema. Polyps may be ulcerated. Endorectal ultrasonography and endorectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) better demonstrate perirectal infiltration.

Small-bowel carcinoid

Plain abdominal radiographs may reveal curvilinear calcification within the abdomen. These are usually smaller than 15 mm in diameter and result from calcification within the tumor.

On barium studies, findings consist of fairly well-defined, round, intraluminal bowel-filling defects. These may be associated with thickening of the valvulae conniventes resulting from interference of the bowel blood supply by the tumor.

With invasion of the mesentery, the mesenteric mass causes rigidity, displacement/stretching, and fixation of small-bowel loops. Desmoplastic reaction from mesenteric invasion causes sharp angulation of a bowel loop or a stellate or spokelike wheel arrangement of adjacent bowel loops.

The tumor often infiltrates the mesentery, provoking an intense fibrotic reaction that results in kinking of the bowel segments; such kinking may in turn cause intestinal obstruction. On a small-bowel barium series, kinking of the small-bowel loops is considered the hallmark of a small-bowel carcinoid tumor.

(See the images of small-bowel carcinoid below.)

Characteristic appearance of small-bowel carcinoid. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Small-bowel dilatation is confined to the upper abdomen. Speckled calcification is noted in a small, circular mass to the right of the mid lumbar spine.

Characteristic appearance of small-bowel carcinoid. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Small-bowel dilatation is confined to the upper abdomen. Speckled calcification is noted in a small, circular mass to the right of the mid lumbar spine.

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid. Barium enema in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous image). Barium enema study shows no obstructive lesion within the large bowel, but the cecum demonstrates an extrinsic impression on its medial side (arrow).

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid. Barium enema in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous image). Barium enema study shows no obstructive lesion within the large bowel, but the cecum demonstrates an extrinsic impression on its medial side (arrow).

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Upper gastrointestinal barium series shows a smooth submucosal mass in the mid jejunum eccentrically placed and associated with thickened valvulae conniventes resulting from bowel edema and proximal small-bowel dilatation. Note the angulation of the bowel and kinking of the jejunum at the site of the submucosal mass.

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Upper gastrointestinal barium series shows a smooth submucosal mass in the mid jejunum eccentrically placed and associated with thickened valvulae conniventes resulting from bowel edema and proximal small-bowel dilatation. Note the angulation of the bowel and kinking of the jejunum at the site of the submucosal mass.

Computed Tomography

When CT scanning reveals a solid mass with spiculated borders and radiating surrounding strands associated with linear strands within the mesenteric fat and kinking of the bowel, a diagnosis of gastrointestinal carcinoid can be made fairly confidently. Hypervascular enhancing liver metastases in the setting of a high index of clinical suspicion can also be a clue to the diagnosis. [18] Liver and lymph node metastases from an intraluminal bowel mass with mesenteric invasion can mimic carcinoids.

Biliary carcinoid

CT scans may demonstrate intrahepatic biliary dilatation associated with an intraductal mass of varying attenuation in the common bile duct. A Klatskin-type tumor representing biliary carcinoid has been reported.

Colon carcinoid

The frequent presence of an extraluminal component can be delineated better on CT scans. Generally, CT scanning is used to stage colon tumors but not to detect them. CT scan findings of colon carcinoids appear similar to those of adenocarcinoma. The tumor may be visualized as a discrete mass or as focal wall thickening.

Gastric carcinoid

In gastric carcinoid, CT scanning may demonstrate thickening of the stomach wall by nodular masses. A large polypoid mass has been reported arising from the lesser curve of the stomach, with areas of low density that were presumed to represent necrosis.

Hepatic carcinoid

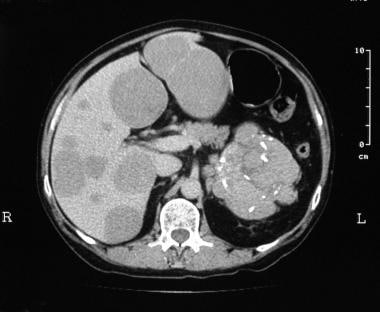

Often multiple, hepatic carcinoids are hypoattenuating on nonenhanced CT scans and are strongly enhancing on contrast-enhanced CT scans. Cystic degeneration may occur. Calcification within carcinoid metastases is not unusual. (See the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows early arterial enhancement of the liver metastases (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows early arterial enhancement of the liver metastases (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows portal venous phase. The metastases appear as negative defects against the normally enhancing liver (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows portal venous phase. The metastases appear as negative defects against the normally enhancing liver (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

Esophageal carcinoid

CT scanning of esophageal carcinoid should be able to demonstrate extraluminal extension and metastases.

Pancreatic carcinoid

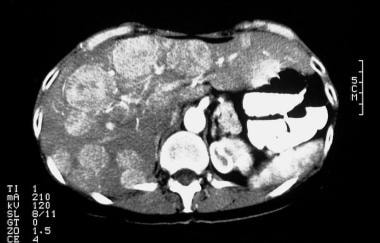

Ultrasonographic and CT scan findings of pancreatic carcinoids are indistinguishable from those of islet cell tumors, but calcification is a clue to the diagnosis. CT scans may show a low-attenuation mass associated with calcification in the pancreas. CT scanning and ultrasonography may demonstrate lymph node and liver metastases. (See the images below.)

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Nonenhanced CT scan through the upper abdomen shows a 9-cm mass in the region of the tail of the pancreas with intratumoral pancreatic calcification and multiple mass lesions within the liver, suggestive of metastases.

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Nonenhanced CT scan through the upper abdomen shows a 9-cm mass in the region of the tail of the pancreas with intratumoral pancreatic calcification and multiple mass lesions within the liver, suggestive of metastases.

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan in the delayed portal venous phase shows enhancement of the pancreatic tail tumor (arrow) with central necrosis (same patient as in the previous image).

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan in the delayed portal venous phase shows enhancement of the pancreatic tail tumor (arrow) with central necrosis (same patient as in the previous image).

Small-bowel carcinoid

CT scanning of small-bowel carcinoid reveals a mass with soft-tissue attenuation and variable size, with spiculated borders and radiating surrounding strands. Calcification may be noted in the tumor. Linear strands within the mesenteric fat probably are thickened and retracted vascular bundles and represent peritumoral desmoplastic reaction. Lymphadenopathy and liver metastases may be visualized on CT scans. Helical CT enteroclysis has been used to detect small-bowel carcinoids and has been found to be more sensitive than conventional barium studies. [19]

In one study, CT enteroclysis showed 100% sensitivity and 96% sensitivity for small-bowel neuroendocrine tumors. Because of higher radiation dose and patient discomfort from nasojejunal intubation, CT enterography has been shown to be a good alternative, identifying 16 of 18 small bowel carcinoids in one study. [11]

In a study by Gupta et al, missed ileal and/or mesenteric findings resulted in a mean diagnostic delay of 40 months (range 4-98 months) and suggested that radiologists make a concerted effort to evaluate the bowel and mesentery in patients with vague abdominal symptoms. [20]

(See the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. Axial CT scan through the mid abdomen shows a mesenteric mass (long arrow) with shaggy borders and probable intratumoral punctate calcification (short arrow).

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. Axial CT scan through the mid abdomen shows a mesenteric mass (long arrow) with shaggy borders and probable intratumoral punctate calcification (short arrow).

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. A 10-mm lower CT section shows stellate radiating and beaded mesenteric neurovascular bundles of the mesentery (arrows) associated with kinking (K) of the small bowel.

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. A 10-mm lower CT section shows stellate radiating and beaded mesenteric neurovascular bundles of the mesentery (arrows) associated with kinking (K) of the small bowel.

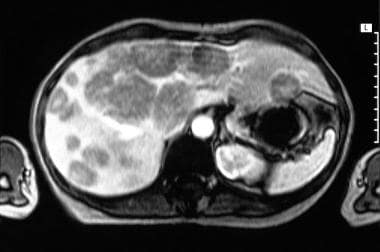

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

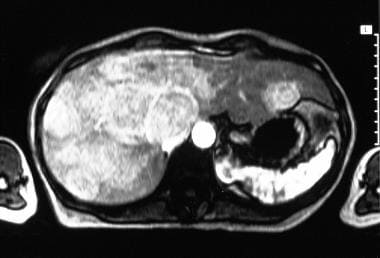

Generally, MRI is not used in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Liver metastases are demonstrated well on MRIs and usually have low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. After the administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent, liver metastases enhance peripherally in the hepatic arterial phase and appear as hypointense defects against the enhancing normal liver in the portal venous phase (see the images below).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows early arterial enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows early arterial enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows portal venous phase enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows portal venous phase enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

MRI demonstrates biliary carcinoids as being hyperintense relative to the liver on T2-weighted images and hypointense relative to the liver on T1-weighted images.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness. For more information, see Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy.

Ultrasonography

On ultrasonograms, carcinoid findings are too nonspecific to offer a confident diagnosis. Any bowel mass or hypervascular liver metastases can result in similar findings.

Biliary carcinoid

Ultrasonography of biliary carcinoid shows evidence of biliary tree dilatation associated with an intraluminal hypoechoic or hyperechoic mass.

Appendiceal carcinoid

A persistent fluid-filled, distended appendix without typical signs of appendicitis has been reported with a carcinoid of the appendix.

Gastric carcinoid

One study using high-resolution transabdominal ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic mass lesion arising from the muscular layer of the stomach. [21]

Hepatic carcinoid

On ultrasonography, liver metastases vary from hypoechoic to hyperechoic and show strong enhancement with intravenous contrast media. Tumors demonstrate peripheral hypervascularity on color and power Doppler images. (See the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the next image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the next image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the previous image for a left-sided image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the previous image for a left-sided image).

Pancreatic carcinoid

Ultrasonographic and CT scan appearances are indistinguishable from those of islet cell tumors, but calcification is a clue to the diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoid. Ultrasonographic findings usually demonstrate a hypoechoic mass, which may be of varying size but tends to be small. Ultrasonography may demonstrate lymph node and liver metastases.

Rectal carcinoid

In rectal carcinoids, perirectal infiltration is better demonstrated on endorectal ultrasonography and endorectal MRI.

Small-bowel carcinoid

Ultrasonography of the bowel can depict bowel tumors, with a pseudokidney sign. Associated lymphadenopathy and liver metastases may be demonstrated on ultrasonograms in cases of small-bowel carcinoid.

Nuclear Imaging

More than 90% of gastrointestinal carcinoids and their metastases are identified using somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy, and accumulation is often seen in clinically unsuspected sites not recognized using other imaging techniques. Fluorine-18 fluorodopa positron emission tomography (18F-dopa–PET) scanning is a useful supplement to morphologic imaging methods. Positron emission tomography scanning with fluorodeoxyglucose(FDG-PET) imaging is useful in poorly differentiated carcinoids when the results of somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy are negative.

Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy is not specific for carcinoids, because uptake also occurs with other lesions that have a high density of somatostatin receptors, such as gastrinomas, glucagonomas, somatostatinomas, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide tumors, neural crest tumors (eg, paragangliomas, medullary thyroid carcinomas, neuroblastomas, pheochromocytomas), oat cell lung carcinomas, and lymphoproliferative disease (eg, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma). In addition, the possibility of uptake in areas of lymphocyte concentration in inflammatory states must be kept in mind. [8]

Gastric carcinoid

Scintigraphy performed with a somatostatin receptor analogue may prove useful in the treatment of patients with hypergastrinemic states, who have an increased incidence of gastric carcinoids. In patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1), localization in the upper abdomen may not be associated with a pancreatic endocrine tumor but rather with a gastric carcinoid.

Pancreatic carcinoid

Somatostatin-analogue scintigraphy has been proven to be sensitive for pancreatic carcinoid; however, the findings are nonspecific, because the study may also show positive findings for islet cell tumors.

Small-bowel carcinoid

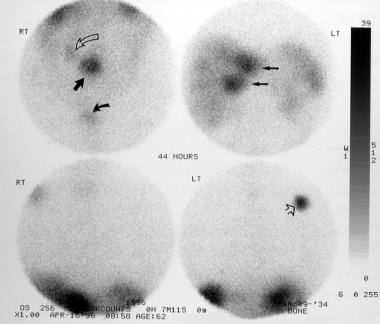

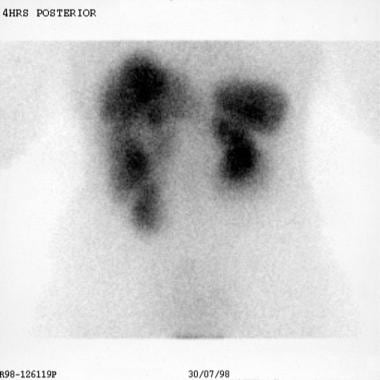

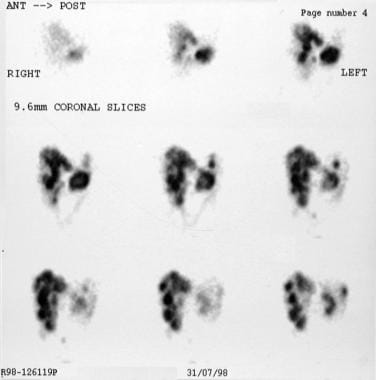

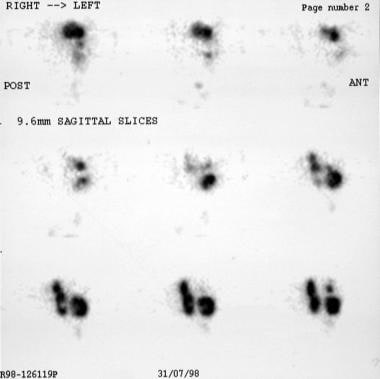

Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy performed with indium-111 (111In) octreotide and 111In pentetreotide is used to image many neuroendocrine tumors, including carcinoids with somatostatin-binding sites. [15] Several studies have shown that somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy is a sensitive and noninvasive technique for imaging primary carcinoid tumors and carcinoid metastatic spread. A refinement of the technique that increases sensitivity is the addition of single photon emission CT (SPECT) scanning. [22] (See the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 44 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved open arrow, top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrow, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved solid arrow (top left image).

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 44 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved open arrow, top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrow, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved solid arrow (top left image).

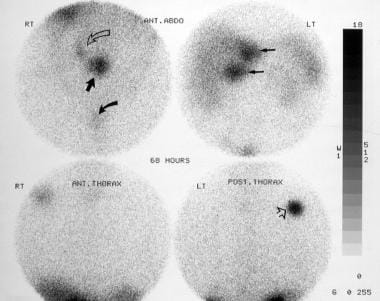

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 68 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved, open arrow; top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrowhead, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved, solid arrow (top left image).

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 68 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved, open arrow; top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrowhead, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved, solid arrow (top left image).

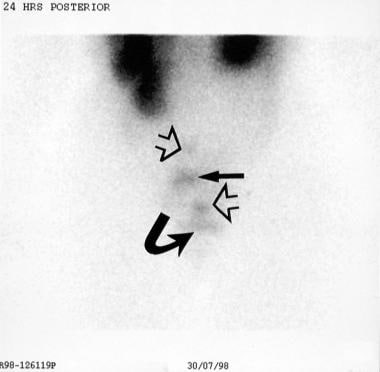

Scintigraphy performed with iodine-123 (123I) meta-iodobenzylguanidine has demonstrated a 44-63% uptake in cases of gastrointestinal carcinoids. [23] A higher frequency of radionuclide uptake is found in midgut carcinoids and tumors with elevated serotonin levels.

Fluorine-18 fluorodopa positron emission tomography (18F-dopa–PET) scanning has been used to image primary gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors and lymph node and organ metastases with promising results. [24, 25]

Positron emission tomography scanning with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET) scanning is useful in poorly differentiated carcinoids and other neuroendocrine tumors, but it should not be used as a first-line imaging agent. FDG-PET scanning is primarily useful when the results of somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy are negative. [26]

(See the images below.)

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion (solid straight arrow), mesenteric metastases (open straight arrows), and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion (solid straight arrow), mesenteric metastases (open straight arrows), and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion, mesenteric metastases, and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow (see also the previous image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion, mesenteric metastases, and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow (see also the previous image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows liver lesions in detail.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows liver lesions in detail.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows the liver lesions in detail (see also the previous image).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows the liver lesions in detail (see also the previous image).

Angiography

Before the advent of cross-sectional imaging, mesenteric angiography provided useful information regarding characterization of small-bowel carcinoids (see the images below). The angiographic appearances of small-bowel carcinoids encountered on angiograms produced for other indications, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, are worth noting. Foreshortening of the bowel occurring with desmoplastic reaction makes mesenteric arteries tortuous and frequently narrowed; it also draws the arteries into a stellate pattern. The areas involved appear hypervascular, but in reality, the number of arteries in the area does not increase. Instead, the arteries contract into a smaller area as a result of fibrosis. [27] Findings are nonspecific and have been reported with sclerosing peritonitis, desmoid tumors, and a carcinoma of the pancreas invading the mesentery.

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows early enhancement of the liver metastases in the arterial phase (see the next image for the capillary phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows early enhancement of the liver metastases in the arterial phase (see the next image for the capillary phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows persisting enhancement of the liver metastases in the capillary phase (see the previous image for the arterial phase).

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows persisting enhancement of the liver metastases in the capillary phase (see the previous image for the arterial phase).

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Right hepatic angiogram shows early enhancement of multiple liver tumors.

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Right hepatic angiogram shows early enhancement of multiple liver tumors.

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Left hepatic angiogram late capillary/early venous phase shows a large, left-lobe tumor with arteriovenous shunting (curved arrow). The pancreatic tumor also derives its blood supply from the left hepatic arterial circulation (straight arrows) (same patient as in the previous image).

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Left hepatic angiogram late capillary/early venous phase shows a large, left-lobe tumor with arteriovenous shunting (curved arrow). The pancreatic tumor also derives its blood supply from the left hepatic arterial circulation (straight arrows) (same patient as in the previous image).

An additional arterial change associated with carcinoids is smooth, multifocal stenosis of the mesenteric arteries distant from the tumor. Tumors seldom show capillary blush or demonstrate early or dense venous drainage. Venous occlusion and mesenteric varices also have been reported. These findings are nonspecific and have been reported with sclerosing peritonitis and with a carcinoma of the pancreas invading the mesentery. Selective hepatic angiography can demonstrate hypervascular liver metastases by demonstrating capillary blush in involved areas, highlighting the potential response of tumors to embolization. [28]

-

Characteristic appearance of small-bowel carcinoid. Plain abdominal radiograph in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Small-bowel dilatation is confined to the upper abdomen. Speckled calcification is noted in a small, circular mass to the right of the mid lumbar spine.

-

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid. Barium enema in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous image). Barium enema study shows no obstructive lesion within the large bowel, but the cecum demonstrates an extrinsic impression on its medial side (arrow).

-

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction (same patient as in the previous 2 images). Upper gastrointestinal barium series shows a smooth submucosal mass in the mid jejunum eccentrically placed and associated with thickened valvulae conniventes resulting from bowel edema and proximal small-bowel dilatation. Note the angulation of the bowel and kinking of the jejunum at the site of the submucosal mass.

-

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 44 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved open arrow, top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrow, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved solid arrow (top left image).

-

Characteristic appearance of small bowel carcinoid in a 55-year-old man presenting with clinical features of bowel obstruction. Images from an indium-111 octreotide scintigraphic study (at 68 h) show the primary lesion (straight arrow, top left image), mesenteric metastases (curved, open arrow; top left image), liver metastases (arrows, top right image), and a rib metastatic deposit (arrowhead, bottom right image); this was confirmed on postmortem study. Bladder activity, which is a normal phenomenon, is marked by a curved, solid arrow (top left image).

-

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. Axial CT scan through the mid abdomen shows a mesenteric mass (long arrow) with shaggy borders and probable intratumoral punctate calcification (short arrow).

-

Characteristic appearance of mesenteric desmoplastic reaction from a carcinoid. A 10-mm lower CT section shows stellate radiating and beaded mesenteric neurovascular bundles of the mesentery (arrows) associated with kinking (K) of the small bowel.

-

Single-contrast-phase image of a barium enema study shows an eccentric narrowing of the splenic flexure associated with paucity of gas in the right hypochondrium resulting from a probable soft-tissue mass.

-

Characteristic angiographic appearance of a carcinoid mesenteric invasion. Arterial/early capillary phase of a superior mesenteric angiogram (same patient as in the previous image) shows the typical radiating configuration of the branches with tortuous peripheral vessels (curved arrows) in the region of the splenic flexure mass. Note the edge of the mesenteric mass (arrowheads) and arterial encasement (straight arrow).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the next image for a left-sided image).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases with different imaging modalities. Axial sonogram through the liver shows multiple fairly well-defined echogenic liver metastases of varying sizes (see the previous image for a left-sided image).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows early arterial enhancement of the liver metastases (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan through the upper abdomen shows portal venous phase. The metastases appear as negative defects against the normally enhancing liver (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows early arterial enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the next image for the portal venous phase).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Gadolinium-enhanced axial MRI through the liver shows portal venous phase enhancement of multiple liver tumors (see the previous image for the hepatic arterial phase).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion (solid straight arrow), mesenteric metastases (open straight arrows), and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow.

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Planar indium-111 octreotide scan shows the primary lesion, mesenteric metastases, and multiple liver metastases. Bladder activity is indicated by a curved arrow (see also the previous image).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows liver lesions in detail.

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Single-photon emission CT scan obtained with indium-111 octreotide shows the liver lesions in detail (see also the previous image).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows early enhancement of the liver metastases in the arterial phase (see the next image for the capillary phase).

-

Characteristic appearance of carcinoid liver metastases. Celiac-axis angiogram shows persisting enhancement of the liver metastases in the capillary phase (see the previous image for the arterial phase).

-

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Nonenhanced CT scan through the upper abdomen shows a 9-cm mass in the region of the tail of the pancreas with intratumoral pancreatic calcification and multiple mass lesions within the liver, suggestive of metastases.

-

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Dynamic contrast-enhanced CT scan in the delayed portal venous phase shows enhancement of the pancreatic tail tumor (arrow) with central necrosis (same patient as in the previous image).

-

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Right hepatic angiogram shows early enhancement of multiple liver tumors.

-

Appearance of pancreatic carcinoid. Left hepatic angiogram late capillary/early venous phase shows a large, left-lobe tumor with arteriovenous shunting (curved arrow). The pancreatic tumor also derives its blood supply from the left hepatic arterial circulation (straight arrows) (same patient as in the previous image).

-

Uptake of iodine-131-meta-iodobenzylguanidine (I-131 MIBG) was more likely if neurohumor levels, particularly serum serotonin, were elevated. There was no relationship of I-131 MIBG uptake to carcinoid syndrome. Courtesy of Dr Ghulam Mustafa Shah Syed.