Practice Essentials

The calcaneus is the most frequently fractured tarsal bone. Calcaneus fractures account for 60% of all tarsal fractures. [1] They account for 1-2% of all fractures of the body, with the majority involving the subtalar joint (about 75%) and the calcaneocuboid joint (about 68%). [2] Calcaneus fractures may occur as a result of falls from heights or from twisting injuries or through a pathologic process such as osteoporosis, cysts, and tumors. About 60% of calcaneal fractures result from falling from a height. Os calcis fractures can be broadly classified into intra-articular and extra-articular types.

The calcaneus functions as a lever arm for the gastrocsoleus complex, providing a foundation or vertical support for one's body weight and providing support for and maintaining the lateral column of the foot. Any fracture that impairs one of these functions substantially affects the person's gait if not restored. [1]

Calcaneus fractures resulting from falls onto the heels from heights are bilateral in 5-9% of patients; they are associated with compression fractures of the lumbar and/or dorsal spine in 10%. These fractures are complicated by a compartment syndrome in 10% of cases, with half of these involving development of clawing of the lesser toes or other chronic problems, such as stiffness and neurovascular dysfunction.

Calcaneus fractures are divided into intra-articular and extra-articular fractures based on involvement of the subtalar joint. Additionally, the posterior facet is involved in intra-articular fractures but is not involved in extra-articular fractures. [3] In adults, about 75% of calcaneal fractures are intra-articular. [1]

According to a study based on data from the American College of Surgeons National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB), of 14,516 patients with calcaneous fractures, concurrent injuries were present in 11,137, with associated lower extremity fractures being present in 61% (the most common of which were other foot and ankle fractures). There were spinal fractures (lumbar spine being the most common) in 23%. In addition, 18% had concurrent head injuries and 15% concurrent thoracic organ injuries. [4]

Soft tissue injuries include subluxation or dislocation of the peroneal tendons from the fibular sulcus, entrapment of neurovascular bundle, and interposition of the flexure hallucis longus tendon between bone fragments from sustentaculum tali.

Displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures are associated with posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Additional risk factors include obesity, smoking and activity levels. [5]

These fractures may remain undiagnosed clinically, as there may be no obvious deformity. Often, a history of the patient falling from a height and landing on his or her heels is helpful, but radiographic examination is essential to confirm fracture. Management of these fractures depends on the type of fracture. Therefore, imaging plays a primary role.

Classification

The Sanders classfiication system is the one most widely used. Other classifications exist, such as Essex-Lopresti, AO-ICI, Zwipp, and Crosby. [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

The Essex-Lopresti classification system consists of 2 types of fractures: (1) joint-depression type with a single vertical fracture line through the angle of Gissane separating the anterior and posterior portions of the calcaneus; and (2) tongue type, which has the same vertical fracture line as a depression type but with another horizontal fracture line running posteriorly, creating a superior posterior fragment. [9, 10]

The Sanders classification system is based on coronal and axial CT scans of the calcaneus. [11, 12] This classification is the one used most frequently today in treatment decision making and reporting of results. This system defines 4 types of calcaneus fractures [9, 13] :

-

Type I consists of a nondisplaced or minimally displaced bony fragment.

-

Type II consists of fractures that are split into 2 parts (2 bony fragments involving the posterior facet, subdivided into types A, B, and C, depending on the medial or lateral location of the fracture line.)

-

Type III are depressed fractures and/or fractures that are split into 3 parts (3 bony fragments, including an additional depressed middle fragment, subdivided into types AB, AC, and BC, depending on the position and location of the fracture lines.)

-

Type IV are 4 comminuted fractures.

Management

The management of calcaneus fractures and their associated soft tissue injuries are controversial. Open reduction and stable internal fixation with a lateral plate and without joint transfixation has been established as standard therapy for displaced intra-articular fractures. [4, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

Good to excellent results are achieved in two thirds to three quarters of all cases, as has been shown in large clinical series. Anatomic reduction of joint congruity and the overall shape of the calcaneus are important prognostic factors. The quality of joint reduction should be proved intraoperatively with the acquisition of Broden views, high-resolution fluoroscopy, or open subtalar arthroscopy. [20, 21, 14, 22, 23]

Zelle et al identified several sociodemographic factors influencing the utilization of surgical treatment of calcaneus fractures in the US patient population. The sociodemographic variables associated with a significantly lower utilization of open reduction and internal fixation included older age, female gender, Medicare, minority status (African Americans and Hispanics), and lower estimated income by zip code. [24]

Imaging modalities

CT imaging is the investigation of choice in calcaneus fractures. [25, 1, 26] Coronal and axial views are generally taken. CT best defines the relationship of bone fragments. [27, 6, 28]

MRI is increasingly being used to characterize ankle sprains, occult fractures, bone bruises, growth-plate injuries, and ligamentous/tendon injuries. MRI is the criterion standard for identifying peroneal tendon injury. This injury is identified by the high signal intensity in tendon on T2-weighted axial views.

Tenography is useful for assessing large lesions of the tendons.

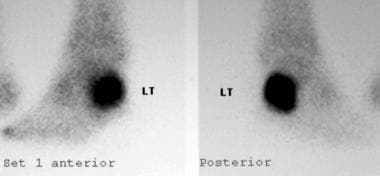

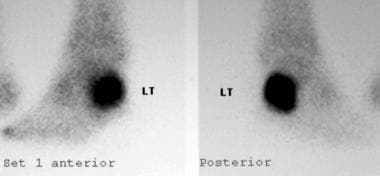

Scintigraphy may be useful in occult fractures and in the differential diagnosis of pathologic fractures. Pathologic features may become apparent on scintigraphy a few weeks before they become apparent on plain radiographs, because the increased osteoblastic activity associated with stress fractures is more easily detected with scintigraphy. [29]

Physical examination usually is required to assess the integrity of tendons and ligaments. Approximately 75% of calcaneus fractures are intra-articular and involve the subtalar articular surface. Because these injuries are associated with a poor prognosis, it is important to identify patients with these fractures.

Conventional radiographs provide a benchmark for the diagnosis of fractures around the ankle in general, and they usually suffice for the diagnosis of the osseous component of the injury [30] ; however, in most cases, supplemental imaging is needed to define characteristics fully, because of the complex anatomy of this region. Comminuted fractures with fragment displacement of the calcaneus are common, and the relationship of the multiple fragments is difficult to appreciate on conventional radiographs.

(See the images of calcaneus fractures below.)

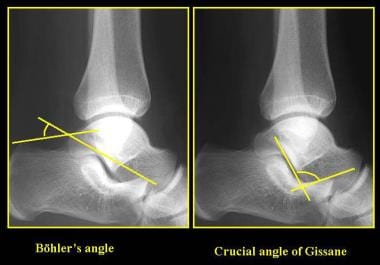

Calcaneus, fractures. The Bohler angle. In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40°. If the angle is reduced, a calcaneal fracture is present; however, a normal angle does not exclude a calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. The Bohler angle. In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40°. If the angle is reduced, a calcaneal fracture is present; however, a normal angle does not exclude a calcaneal fracture.

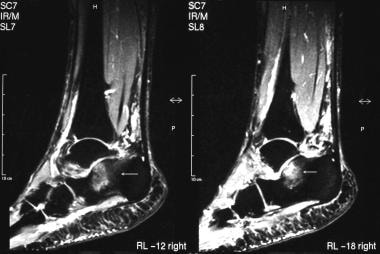

Calcaneus, fractures. Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sagittal MRI demonstrates high signal intensity at the anterior and middle processes. This represents bony edema secondary to a fracture, which is not appreciated on the plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sagittal MRI demonstrates high signal intensity at the anterior and middle processes. This represents bony edema secondary to a fracture, which is not appreciated on the plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scan depicts a stress fracture of the calcaneus, which was not apparent on plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scan depicts a stress fracture of the calcaneus, which was not apparent on plain radiographs.

Limitations of techniques

Conventional radiographs may be negative in cases involving subtle fractures, particularly in cases involving stress fractures. Comminuted fractures and displacement are common in fractures of the calcaneus, and the relationship of the multiple fragments is difficult to appreciate on conventional radiographs.

CT is the modality of choice, especially in complex fracture patterns, although it is expensive and it imparts a relatively high dose of radiation; it should be used sparingly in young patients or in pregnant patients. It is noteworthy that CT tends to be somewhat overutilized in the United States.

MRI is expensive and may cause problems in patients with claustrophobia. MRI is sensitive in the immediate documentation of stress changes in osseous structures. MRI is well known to show even minor stress changes (eg, after a marathon) that occur before the actual stress fracture.

A severe bone contusion is associated with multiple microfractures, whereas a stress fracture involves a linear component; the distinction between the 2 diagnoses may seem arbitrary.

In the absence of a linear component, it may be difficult to distinguish an underlying severe stress reaction associated with a bone contusion from a stress fracture on MRI. Bone contusion associated with a stress fracture may be difficult to distinguish from red marrow. With MRI, it may be difficult to detect small intra-articular fragments—a fact that likely limits the use of MRI on a routine basis.

Scintigraphy is sensitive in imaging bone trauma but lacks the specificity and the spatial resolution that MRI provides. A physiologic periosteal reaction, bone tumor, avascular necrosis, plantar fasciitis, or bone spur can cause false-positive findings.

Radiography

Conventional radiography

Conventional radiographic examination consists of axial and lateral views of the calcaneus and an anteroposterior (AP) view of the foot (see the images below). However, because of the complexity of the anatomy, multiple radiographic views are often necessary. Giannestras and Sammarco suggested that multiple views be used, including the oblique view. [31] Radiographs of the dorsal and lumbar spine are also often indicated, because an associated fracture is seen in a vertebral body in 10% of all patients. Further fractures of the tibia and fibula are seen in 9% of patients. Calcaneus fractures are bilateral in 5% of patients.

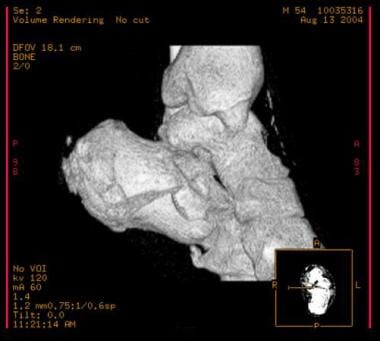

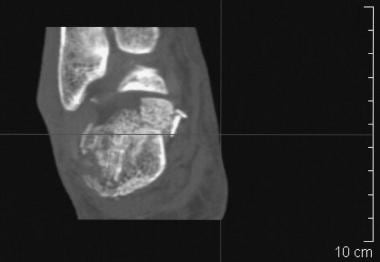

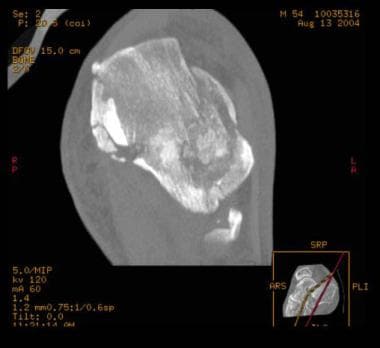

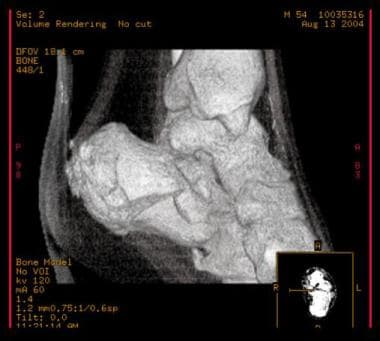

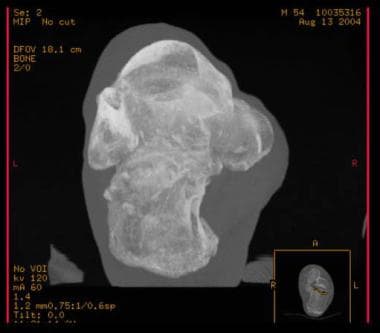

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiographs and CT scans in various projections and 3-dimensional rendering show the value of each modality.

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiographs and CT scans in various projections and 3-dimensional rendering show the value of each modality.

(For the axial [Harris] view, see the images below.)

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) view. Note the fracture line divides the calcaneus into anteromedial and posterolateral fragments.

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) view. Note the fracture line divides the calcaneus into anteromedial and posterolateral fragments.

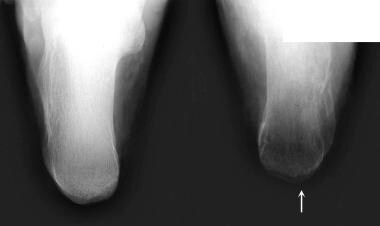

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) views of both calcanei show a left calcaneal fracture. Bilateral calcaneal fractures are seen in 5-9%.

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) views of both calcanei show a left calcaneal fracture. Bilateral calcaneal fractures are seen in 5-9%.

(For Rowe type fractures, see the images below.)

Calcaneus, fractures. Avulsion fracture. Rowe type II beak/avulsion fracture of the Achilles tendon. Rowe classifies fractures into 5 groups. Groups I–III do not involve the subtalar joint. Groups IV and V involve the subtalar joint and represented almost 60% of the originally described series.

Calcaneus, fractures. Avulsion fracture. Rowe type II beak/avulsion fracture of the Achilles tendon. Rowe classifies fractures into 5 groups. Groups I–III do not involve the subtalar joint. Groups IV and V involve the subtalar joint and represented almost 60% of the originally described series.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture involving the subtalar joint without central depression.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture involving the subtalar joint without central depression.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture. This type represents almost a quarter of the fractures in the original series.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture. This type represents almost a quarter of the fractures in the original series.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V calcaneal fracture. This is a comminuted fracture involving the subtalar joint; it has a central depression.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V calcaneal fracture. This is a comminuted fracture involving the subtalar joint; it has a central depression.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V, intra-articular calcaneal fracture. Intra-articular fractures represent 75% of all calcaneal fractures.

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V, intra-articular calcaneal fracture. Intra-articular fractures represent 75% of all calcaneal fractures.

The Essex-Lopresti classification system consists of 2 types of fractures: (1) joint-depression type with a single vertical fracture line through the angle of Gissane separating the anterior and posterior portions of the calcaneus; and (2) tongue type, which has the same vertical fracture line as a depression type but with another horizontal fracture line running posteriorly, creating a superior posterior fragment. [9, 10]

(For Essex-Lopresti fractures, see the images below.)

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. The fracture line extends posteriorly to the tuberosity.

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. The fracture line extends posteriorly to the tuberosity.

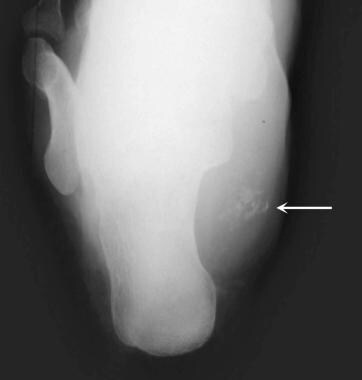

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. Note loss of the crucial angle of Gissane.

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. Note loss of the crucial angle of Gissane.

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti depression-type calcaneal fracture. Depression-type fractures are more common than tongue type. The fracture line extends along the calcaneus behind the subtalar joint.

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti depression-type calcaneal fracture. Depression-type fractures are more common than tongue type. The fracture line extends along the calcaneus behind the subtalar joint.

(Normal variants of calcaneus fractures are shown in the images below.)

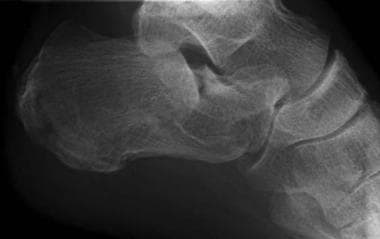

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Old calcaneal fracture. Dorsoposterior (DP) and lateral views of the foot demonstrate an old Essex-Lopresti depressed-type calcaneal fracture. The patient now has degenerative change at the subtalar joint. Essex-Lopresti describes 2 fracture types involving the subtalar joint. The depression type and the tongue type. Note flattening of the Bohler angle.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Old calcaneal fracture. Dorsoposterior (DP) and lateral views of the foot demonstrate an old Essex-Lopresti depressed-type calcaneal fracture. The patient now has degenerative change at the subtalar joint. Essex-Lopresti describes 2 fracture types involving the subtalar joint. The depression type and the tongue type. Note flattening of the Bohler angle.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Achilles tendonitis calcification is a differential diagnosis in cases of suspected calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Achilles tendonitis calcification is a differential diagnosis in cases of suspected calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented with heel pain following trauma. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs show features of plantar fasciitis. Note the calcaneal spur and calcification in the distribution of plantar fascia.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented with heel pain following trauma. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs show features of plantar fasciitis. Note the calcaneal spur and calcification in the distribution of plantar fascia.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Lateral radiograph of the calcaneus on the same patient as in Image 33 shows calcification of the plantar fascia.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Lateral radiograph of the calcaneus on the same patient as in Image 33 shows calcification of the plantar fascia.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This normal variant—an unfused secondary ossification center—must not be mistaken for a calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This normal variant—an unfused secondary ossification center—must not be mistaken for a calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

Calcaneus, fractures. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma.

Calcaneus, fractures. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma. (See also the previous image.)

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma. (See also the previous image.)

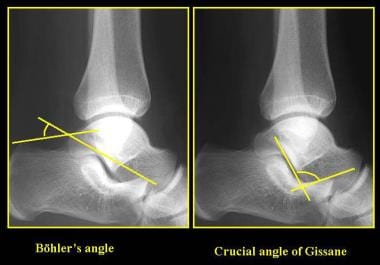

Lateral view and the Bohler angle

The lateral view is the primary projection on which a diagnosis of a fracture is made, although some subtle fractures may be missed when reliance is placed on a lateral view only. Lateral views show the Bohler tuber angle and the crucial angle of Gissane clearly. However, normal Bohler and Gissane angles do not rule out a fracture. The Bohler angle may be depressed on plain radiographs, and the critical angle of Gissane may be increased; normal angle is 130-145º. [9]

Lorenz Bohler described the tuber-joint angle (the so-called Bohler angle). In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40° (see the image below).

Calcaneus, fractures. The Bohler angle. In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40°. If the angle is reduced, a calcaneal fracture is present; however, a normal angle does not exclude a calcaneal fracture.

Calcaneus, fractures. The Bohler angle. In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40°. If the angle is reduced, a calcaneal fracture is present; however, a normal angle does not exclude a calcaneal fracture.

In intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus, the subtalar joint is depressed, causing a decrease in the Bohler angle. The Bohler angle may also be decreased in some calcaneus fractures that do not involve the subtalar joint. A flat Bohler angle is associated with intra-articular fractures; in such cases, the prognosis is poorer than it is in cases in which the angle is maintained. [18, 32]

In a study of 424 patients with calcaneus fractures, the mean Bohler angle was 29.4º. An angle of 20º or less was highly accurate in determining the presence of a fracture. An angle below 25º was moderately predictive. [32]

The critical angle of Gissane is an angle drawn between 2 lines on plain film, with the first line drawn along the anterior downward slope of the calcaneus, and the second drawn along the superior upward slope. A normal angle is 130-145º. [9]

Axial view

The axial view is used to evaluate the subtalar joint and the width of the calcaneus (see the images below). Normally, in an adult, the calcaneus measures 30-35 mm in width. A fracture may cause the calcaneus to increase in width; the expanded, fractured calcaneus may then impinge upon the fibula, causing entrapment of the peroneal tendons.

AP view

The AP view is essential for evaluating the calcaneocuboid joint (see the image below). This view also demonstrates avulsion fractures of the anterior lateral aspect of the calcaneus.

Calcaneus, fractures. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of a patient following trauma demonstrate no apparent bony injury.

Calcaneus, fractures. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of a patient following trauma demonstrate no apparent bony injury.

Oblique views

Various oblique views have been advocated. These are valuable in demonstrating fracture extending into the joint and loss of parallelism of articular surfaces.

Oblique views (ie, the Broden view) can define incongruity of the subtalar joint. These images are obtained by internally rotating the foot 45°, with the heel resting on the radiographic plate; the beam is directed cephalad in angles varying from 10° to 40°.

Peroneal tenography

Peroneal tenography involves injecting iodinated contrast material into the peroneal tendon sheaths under fluoroscopic guidance. The contrast material then descends behind the lateral malleolus.

Peroneal tenography helps in diagnosing abnormal conditions after calcaneus fractures or other trauma, such as peroneal tendon dislocation resulting from skiing accidents. Compression of the tendon sheath associated with partial or complete obstruction of the flow of contrast and tendon displacement may be depicted. Aspiration of the injected contrast material following use of a local anesthetic may relieve pain and help determine the source of the pain.

Degree of confidence

Conventional radiography is the primary imaging modality in cases of suspected ankle fractures. Radiography may be the only modality required, though it is not always capable of depicting the relationship of bone fragments to the joint and to each other.

In complex fractures, CT scanning is used in addition to conventional radiography.

Conventional radiography is inexpensive and is universally available. It exposes the patient to a modest radiation dose. Study results are reproducible, and the images are easy to interpret.

Measuring the various angles not only enables reliable diagnosis but also helps in determining the ultimate prognosis.

False positives/negatives

Various anatomic variants in the calcaneus may mimic fractures.

Os subcalcis is a calcaneal apophysis seen in the adolescent on the posteroinferior plantar surface of the calcaneus, which is normally not visible on lateral radiographs.

The unfused secondary ossification center for calcaneal tuberosity may produce a simulated fracture.

Failed union of a portion of calcaneal apophysis in an adult may superficially mimic a fracture.

Calcaneus secundarius is an accessory ossicle attached to the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus.

The sustentaculum tali can produce a simulated fracture on the superior margin on lateral views.

Prominent trabeculation can simulate a fracture on plain radiographs and CT scans.

False-negative radiographic findings may occur when images show subtle fracture lines. These fractures may be confirmed with scintigraphy and/or MRI.

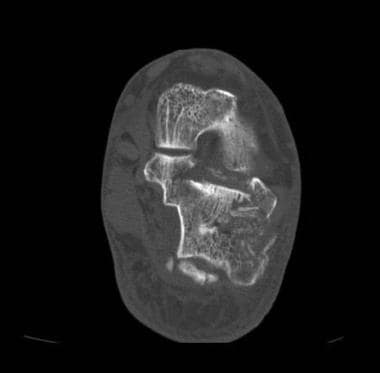

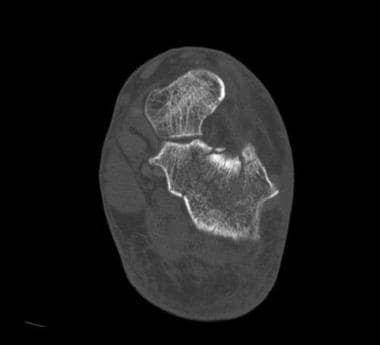

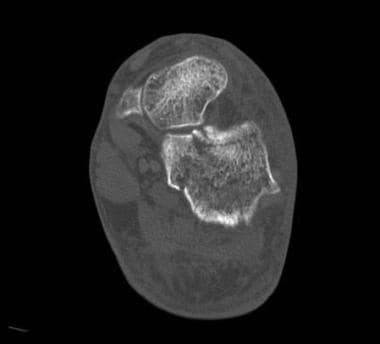

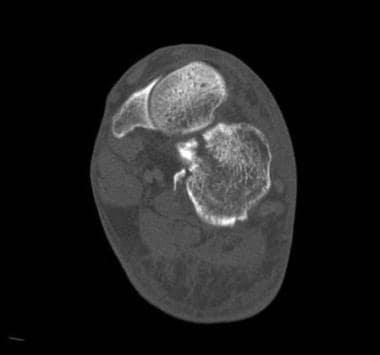

Computed Tomography

CT is the modality of choice for calcaneus fractures. Coronal and axial views are generally obtained. Involvement of the subtalar joint can be clearly appreciated, and CT enables optimal evaluation of calcaneal widening. [25, 1, 26]

(See the images below.)

Sanders classification system

Sanders developed a classification system based on coronal and axial CT scans of the calcaneus. [11, 12] This classification is the one used most frequently today in treatment decision making and reporting of results. This system defines 4 types of calcaneus fractures [9, 13] :

-

Type I consists of a nondisplaced or minimally displaced bony fragment.

-

Type II consists of fractures that are split into 2 parts (2 bony fragments involving the posterior facet, subdivided into types A, B, and C, depending on the medial or lateral location of the fracture line.)

-

Type III are depressed fractures and/or fractures that are split into 3 parts (3 bony fragments, including an additional depressed middle fragment, subdivided into types AB, AC, and BC, depending on the position and location of the fracture lines.)

-

Type IV are 4 comminuted fractures (see the images below).

Patients with type 1 injuries do well with nonoperative treatment; patients with injuries of types 2 and 3 may be treated effectively with open reduction and internal fixation; and type 4 injuries defy operative reduction. [15]

Stress fractures

CT is occasionally performed to diagnose stress fractures. CT is capable of demonstrating disruption of the bony cortex and periostitis in most individuals. Its sensitivity is higher than that of plain radiography. However, compared with MRI or bone scanning, CT has low sensitivity for stress reactions and fractures; this leads to a high rate of false-negative results.

Soft tissue abnormalities

The risk for peroneal tendon instability increases with fracture severity. The presence of a lateral malleolar fleck sign suggests peroneal tendon instability. [3]

Bradley and Davies studied soft tissue abnormalities occurring after calcaneus fractures [33] and determined that CT in both the immediate postfracture period and in the late phase may be used to detect and classify soft tissue changes.

CT scans of 50 acute calcaneus fractures were compared with scans of 77 fractures in which the date of injury preceded the CT study by 6 months or more. The investigators found that 42 of the fractures (84%) in the acute group and 55 in the chronic group (71%) were classified as intra-articular; these fractures formed the basis of the study.

The alterations in the position of the peroneal tendons in the 2 groups were similar, with a 5% or smaller difference in each category. In the acute group, the peroneal tendons were of normal location in 40.4% of cases; in 11.9% of cases, the peroneal tendons were entrapped by bone; subluxation was evident in 33.3% of cases; and dislocations were present in 14.2% of cases. Structural abnormalities of the peroneal tendons and surrounding soft tissues were identified in 52.4% of patients in the acute group and in 61.1% of patients in the chronic group.

The incidence of partial rupture of the peroneal tendons in the chronic group was approximately one third that in the acute group, but the low incidence of complete tendon rupture remained unchanged.

The inference from these observations is that, in most cases, partial peroneal tendon rupture is reversible, whereas complete rupture is not. Seven fractures were common to both series; from this limited group, the identification of hemorrhage around the peroneal tendons in the acute phase was shown not to be related to the subsequent development of chronic stenosing tenosynovitis. Various abnormalities of the medial tendons of the hindfoot were identified in 17% of patients in the acute group and in 18% of patients in the chronic group.

Degree of confidence

CT is the modality of choice for calcaneus fractures. Confidence in the diagnosis made on the basis of a positive CT scan of the affected area is high.

Furey evaluated 30 calcaneus fractures to assess the degree of interobserver variability by using the Sanders classification system and found that the Sanders classification system achieved moderate agreement among users and was thus useful. [34] Thirty CT scans of calcaneus fractures taken over a 5-year period in 2 tertiary care centers were chosen randomly. Three orthopedic surgeons and 1 senior orthopedic resident reviewed the scans and classified the fractures.

The results were analyzed by using a weighted kappa test that included the subcategories. The weighted kappa value was 0.56, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.45-0.67. The subcategories of the classification were further combined, and a second analysis was performed to assess agreement between general classes. The weighted kappa value was 0.48, with a 95% CI of 0.37-0.59.

Brunner et al conducted a study to evaluate the impact of 3-dimensional (3D) CT volume rendering on the interobserver and intraobserver reliability of 6 commonly used classification systems in the assessment of calcaneal fractures. In the study, 4 independent observers with different levels of clinical training evaluated 64 fractures according to the classifications of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA), Essex-Lopresti, Sanders, Crosby, Zwipp, and Regazzoni, using 2-dimensional CT scans with multiplanar reconstructions and 3D volume-rendering reconstructions. The results revealed that 3D reconstructions may have other benefits not evaluated in the presented study and may give useful information not captured by current classification systems. [35]

In cases of stress fractures, a well-defined cortical discontinuity is suggestive of a fracture. However, the rate of false-negative results is high. Therefore, in the appropriate clinical setting, CT may be skipped, and either MRI or bone scanning may be performed.

Repeat CT scanning is not an attractive alternative, though it may result in the correct diagnosis because of interval development of necrosis. Prominent trabeculation can simulate a fracture on CT.

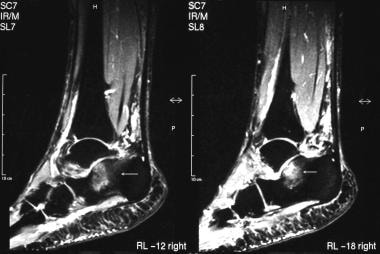

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is generally not used in the diagnosis of calcaneus fractures. However, MRI is often useful in patients with suspected stress fractures, particularly those with severe osteoporosis in whom skeletal scintigraphy may produce false-negative findings as a result of generalized poor uptake of tracer (see the images below).

Calcaneus, fractures. Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sagittal MRI demonstrates high signal intensity at the anterior and middle processes. This represents bony edema secondary to a fracture, which is not appreciated on the plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sagittal MRI demonstrates high signal intensity at the anterior and middle processes. This represents bony edema secondary to a fracture, which is not appreciated on the plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. T2-weighted sagittal MRIs demonstrate fibrosis of the peroneal tendon sheath following a past calcaneus fracture, which is a recognized complication of calcaneal fractures.

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. T2-weighted sagittal MRIs demonstrate fibrosis of the peroneal tendon sheath following a past calcaneus fracture, which is a recognized complication of calcaneal fractures.

MRI is highly sensitive for the detection of bone marrow changes. Anatomic resolution is better with MRI than with radionuclide imaging. Bone contusions are also well depicted on MRI.

On MRI, stress fractures typically appear as areas of low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images. They often appear as a band of low signal intensity that arises from the cortex of the bone and extends perpendicular to the surface of the bone. If imaging is performed within 4 weeks of the injury, an area of high signal intensity often can be observed on T2-weighted images; this represents associated edema or hemorrhage.

Fat-suppressed sequences are sensitive to bone marrow edema, which accompanies bone bruises and stress fractures.

MRI also has a place in the investigation of ligamentous and tendon injury in association with calcaneus fractures.

Degree of confidence

Confidence in the imaging findings is usually high in a patient who is believed on clinical grounds to have a stress fracture. MRI findings may be positive within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms. Stress fractures may take longer to become evident on radionuclide bone scans, particularly in patients with osteoporosis. MRI may be used to evaluate tendon and ligamentous injuries noninvasively.

Many pathologies can cause bone marrow edema; in patients with a history of trauma, the presence of edema may lead to an incorrect diagnosis of fracture. Pathologies associated with edema include osteomyelitis and neoplasm. The linear hypointensity is usually helpful in identifying stress fractures.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography of the foot region is indicated for the evaluation of the presence of foreign bodies. It is also indicated for the evaluation of dislocation of the peroneal tendons; lesions in the flexor and extensor tendons; and osseous capsular and ligamentous avulsions.

Signs of pathology that are apparent on sonograms of soft tissue include articular effusion, fluid conglomeration, ossification, and the development of vascular lesions.

Ultrasonography is useful for detecting all types of peroneal lesions. In particular, real-time ultrasonography may be performed to assess dynamic stability. [36, 37, 38]

In a study of 8 patients in whom ultrasonography was used to diagnose a calcaneal stress fracture, Bianchi et al found that thickening of the periosteum and subcutaneous edema were present in all patients and that cortical irregularities were present in 6 patients. Color Doppler imaging showed local hypervascular changes of the periosteum in all patients. [39]

Ultrasonography is operator and institution dependent, and musculoskeletal ultrasonography is not universally available. Sonograms of the hindfoot and ankle commonly depict articular, bursal, and tendon-sheath fluid in asymptomatic volunteers. The presence of fluid in these locations, even when unilateral or asymmetric, does not necessarily imply underlying abnormality.

Nuclear Imaging

Bone scintigraphy is typically utilized in cases in which radiographic and CT findings are negative for suspected fractures (see the image below).

Calcaneus, fractures. Technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scan depicts a stress fracture of the calcaneus, which was not apparent on plain radiographs.

Calcaneus, fractures. Technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scan depicts a stress fracture of the calcaneus, which was not apparent on plain radiographs.

Stress fractures are relatively easily diagnosed with skeletal scintigraphy. The degree of confidence is high, because the diagnosis of stress fracture may be reliably excluded when bone scans are normal. Stress fractures are associated with hyperemia in the first 2 phases of the 3-phase bone scan. The first phase demonstrates increased flow of blood in the arterial phase, and the second phase demonstrates tissue hyperemia. The third phase demonstrates increased osteoblastic activity in response to the stress fracture. [40] The injury is manifested by increased radionuclide uptake at the fracture site.

In adults, detection of hyperemia is straightforward, but problems may arise in children, because in children, the uptake of radionuclide is often increased around the epiphyses; contralateral images are often needed for comparison. In children, epiphyseal uptake may mask increased radionuclide uptake caused by osteoblastic activity.

Osteomyelitis, calcaneonavicular bars, osteoarthritis, erosive arthritis, tumors, and pathologic fractures may have an appearance similar to that of fractures on scintigraphy. In patients with multiple stress fractures, an accurate determination of the age of the fracture is not always possible. In patients with severe osteoporosis, the level of tracer uptake by the bone may be too low, and false-negative results may be produced.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Calcaneus anatomy.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Calcaneus anatomy.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Calcaneus anatomy.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Location of fracture lines.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti classification.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe classification.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Sander CT classification.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. The Bohler angle. In determining the Bohler angle, a line is drawn between the posterior superior aspect of the calcaneus and the highest point of the posterior subtalar articular surface; a second line, which intersects the first, is drawn from the highest point of the anterior process to the posterior margin of the subtalar surface. The angle that results from their intersection measures 20-40°. If the angle is reduced, a calcaneal fracture is present; however, a normal angle does not exclude a calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) view demonstrates a calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) view. Note the fracture line divides the calcaneus into anteromedial and posterolateral fragments.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Axial (Harris) views of both calcanei show a left calcaneal fracture. Bilateral calcaneal fractures are seen in 5-9%.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Avulsion fracture. Rowe type II beak/avulsion fracture of the Achilles tendon. Rowe classifies fractures into 5 groups. Groups I–III do not involve the subtalar joint. Groups IV and V involve the subtalar joint and represented almost 60% of the originally described series.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Lateral and axial radiographs demonstrate a Rowe type II calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Subtle, extra-articular Rowe type III calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture involving the subtalar joint without central depression.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type IV calcaneal fracture. This type represents almost a quarter of the fractures in the original series.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V calcaneal fracture. This is a comminuted fracture involving the subtalar joint; it has a central depression.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Rowe type V, intra-articular calcaneal fracture. Intra-articular fractures represent 75% of all calcaneal fractures.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. The fracture line extends posteriorly to the tuberosity.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti tongue-type calcaneal fracture. Note loss of the crucial angle of Gissane.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti depression-type calcaneal fracture. Depression-type fractures are more common than tongue type. The fracture line extends along the calcaneus behind the subtalar joint.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti depression-type calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex-Lopresti depression-type calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Essex Lopresti depression-type fracture.

-

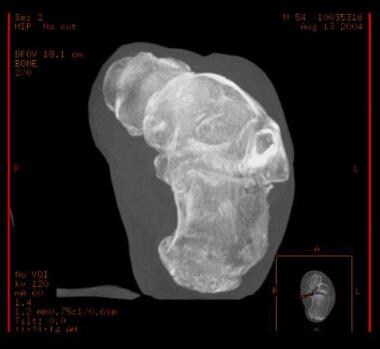

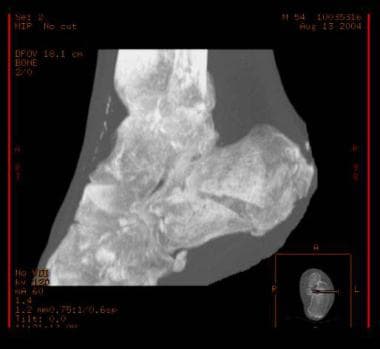

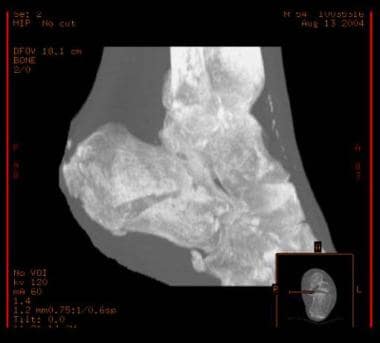

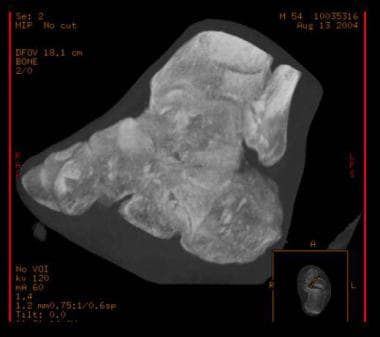

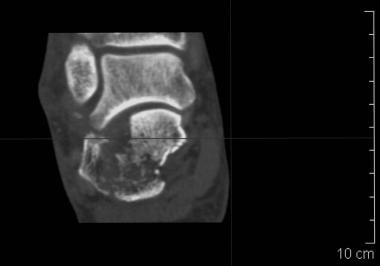

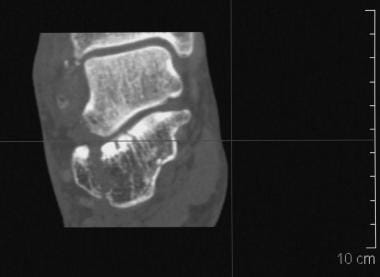

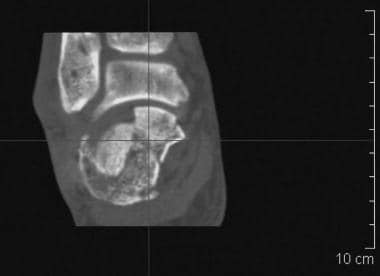

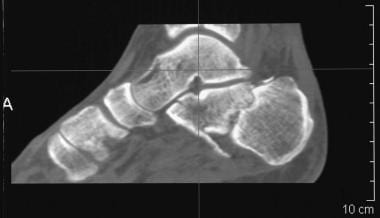

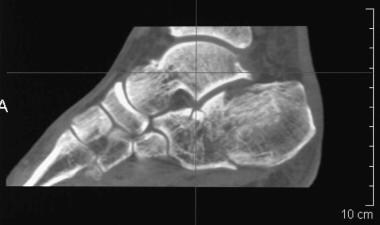

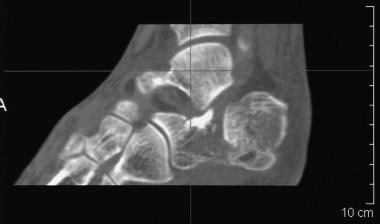

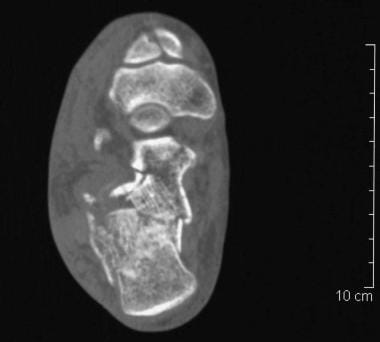

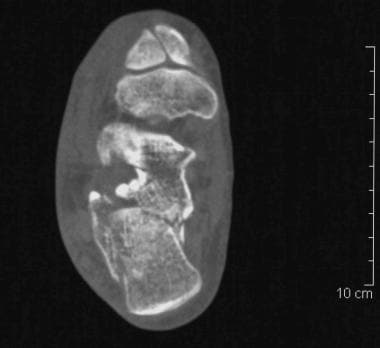

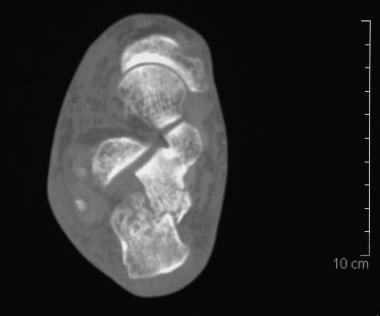

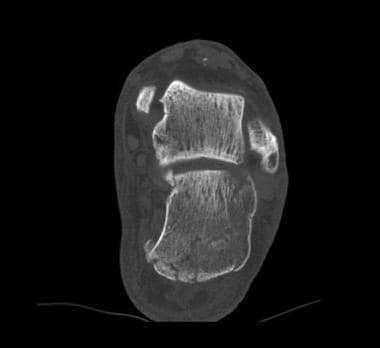

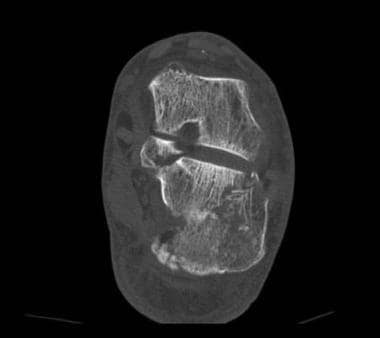

Calcaneus, fractures. CT image demonstrates a comminuted, Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Saunders type IV calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiographs and CT scans in various projections and 3-dimensional rendering show the value of each modality.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiograph.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiograph.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Plain radiograph.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. CT scan.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of a patient following trauma demonstrate no apparent bony injury.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sagittal MRI demonstrates high signal intensity at the anterior and middle processes. This represents bony edema secondary to a fracture, which is not appreciated on the plain radiographs.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Technetium-99m diphosphonate bone scan depicts a stress fracture of the calcaneus, which was not apparent on plain radiographs.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Old calcaneal fracture. Dorsoposterior (DP) and lateral views of the foot demonstrate an old Essex-Lopresti depressed-type calcaneal fracture. The patient now has degenerative change at the subtalar joint. Essex-Lopresti describes 2 fracture types involving the subtalar joint. The depression type and the tongue type. Note flattening of the Bohler angle.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Achilles tendonitis calcification is a differential diagnosis in cases of suspected calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented with heel pain following trauma. Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs show features of plantar fasciitis. Note the calcaneal spur and calcification in the distribution of plantar fascia.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Lateral radiograph of the calcaneus on the same patient as in Image 33 shows calcification of the plantar fascia.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This normal variant—an unfused secondary ossification center—must not be mistaken for a calcaneal fracture.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. Calcaneal cysts are normal variants and should not be confused with pathology.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma.

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. This patient presented following trauma to the calcaneus. Axial radiograph shows soft tissue swelling with amorphous calcification. Biopsy proved a malignant synovioma. (See also the previous image.)

-

Calcaneus, fractures. Normal variants, complications, and differential diagnosis. T2-weighted sagittal MRIs demonstrate fibrosis of the peroneal tendon sheath following a past calcaneus fracture, which is a recognized complication of calcaneal fractures.