Practice Essentials

The term "branchial apparatus" refers to the embryologic precursors that develop into the tissue of the neck. Many developmental anomalies of the branchial apparatus have been identified: cysts, fistulas, sinuses, ectopic glands, and malformations of head and neck structures. Although relatively rare, these anomalies constitute the second major cause of head and neck pathologies in childhood. Branchial cleft cysts are often incorrectly diagnosed and overlooked in the differential diagnosis. Thus, the diagnosis is often delayed, resulting in mismanagement of affected patients. A branchial cyst should be suspected in any patient with swelling in the lateral aspect of the neck, regardless of whether the swelling is solid or cystic, painful or painless. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Branchial cleft cysts are benign, but morbidity results from superinfection, mass effect, and surgical complications. Primary branchiogenic carcinoma is rare but must be suspected in the presence of cervical masses, especially in patients older than 40 years. [10]

The patient’s medical history and clinical manifestations guide the clinician in suspecting branchial cleft cysts; confirmatory imaging modalities include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography, and rarely fine-needle aspiration. The usual mainstay of management is surgical excision. Cyst location, clinical picture, and radiologic correlation, along with strong suspicion for the condition, facilitate diagnosis. [1]

Anatomy

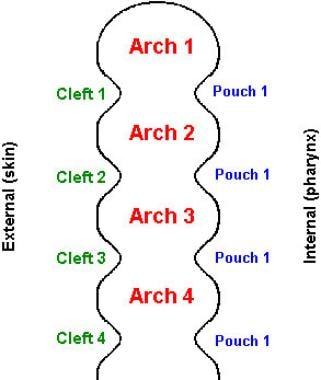

A basic understanding of cervical embryology is essential to the discussion of branchial anomalies. [11, 12, 13, 14, 15] The branchial apparatus develops during the second to sixth weeks of fetal life. At this stage, the neck is shaped like a hollow tube with circumferential ridges, which are termed branchial arches. Branchial arches develop into the musculoskeletal and vascular components of the head and neck. The thinner regions between the arches are termed clefts (on the outside of the fetus) and pouches (on the inside of the fetus) (see the image below). Branchial pouches develop into the middle ear, tonsils, thymus, and parathyroid glands.

The first branchial cleft develops into the external auditory canal. The second, third, and fourth branchial clefts merge to form the sinus of His, which normally becomes involuted. When a branchial cleft is not properly involuted, a branchial cleft cyst forms. Occasionally, both the branchial pouch and the branchial cleft fail to become involuted, and a complete fistula forms between the pharynx and the skin.

First branchial cleft cysts

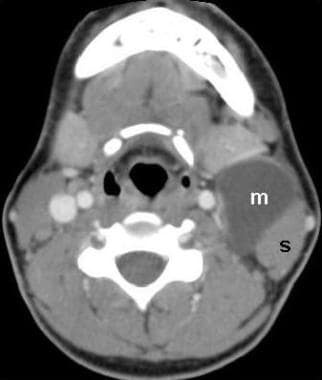

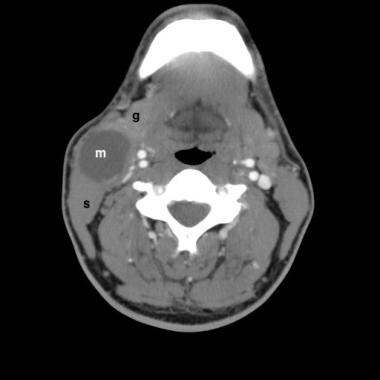

First branchial cleft cysts account for 5-25% of all branchial cleft abnormalities and are divided into type I and type II based on anatomic and histologic features. [16] Type I cysts are located near the external auditory canal, most commonly inferior and posterior to the tragus (base of the ear). However, CT and MRI studies should include the parotid area, as it may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis. [17] Type II cysts appear at the angle of the mandible and may involve the submandibular gland (see the image below). [18] A retrospective study of CT results examined the relation between first branchial cleft anomalies and the facial nerve in 41 patients. [19] The researchers concluded that the younger the patient, the more likely the lesion would be deep to the facial nerve.

Diagnosis of first branchial cleft anomalies can be difficult and depends on radiologic and histologic findings. In contrast, required treatment is surgical removal because of the high risk of infection or malignancy. This rare condition is a potential diagnostic option that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cysts of the external auditory canal in both children and older adults. [16]

First branchial cleft cyst, type II. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals an ill-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) posterior to the right submandibular gland (g).

First branchial cleft cyst, type II. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals an ill-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) posterior to the right submandibular gland (g).

Second branchial cleft cysts

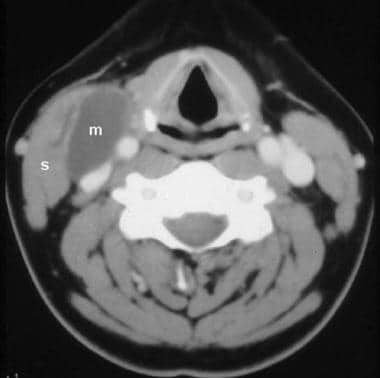

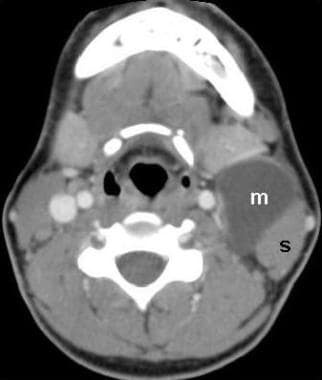

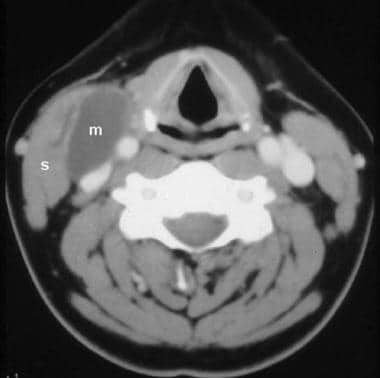

The second branchial cleft accounts for up to 95% of branchial anomalies, which are most frequently identified along the anterior border of the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and adjacent to the muscle. [2] However, these cysts may present anywhere along the course of a second branchial fistula, which proceeds from the skin of the lateral neck, between the internal and external carotid arteries, and into the palatine tonsil (see the image below). Therefore, a second branchial cleft cyst is part of the differential diagnosis of a parapharyngeal mass.

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) on the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) on the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

In a study of contrast-enhanced CT and MRI findings of second branchial cleft cysts (SBCCs) in 11 patients, SBCCs were found to be identifiable as cysts with eccentric and smooth wall thickening. Wall thickening was observed in all 11 patients. Wall thickening was identified as small (1-25%) in 4 of 11 patients (36%), moderate (26-50%) in 6 of 11 (54%), and extensive (51-75%) in 1 of 11 (9%). Mild homogeneous enhancement of the thickened wall was observed in 7 patients on CT images. Signal intensity of the thickened wall on T2-weighted images was isointense relative to that of normal lymph nodes in 7 patients and mildly hyperintense in 1 patient. Maximum thickness ranged from 2 to 4 mm. [20]

Third branchial cleft cysts

Third branchial cleft cysts are rare. A third branchial fistula extends from the same skin location as a second branchial fistula (recall that the clefts merge during development); however, a third branchial fistula courses posterior to the carotid arteries and pierces the thyrohyoid membrane to enter the larynx, terminating on the lateral aspect of the pyriform sinus. Third branchial cleft cysts occur anywhere along that course (eg, inside the larynx), but they are characteristically located deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see the image below).

Third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the thyroid cartilage reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

Third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the thyroid cartilage reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

Fourth branchial cleft cysts

Fourth branchial cleft cysts are extremely rare. A fourth branchial fistula arises from the lateral neck and parallels the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (around the aorta on the left and around the subclavian artery on the right), terminating in the apex of the pyriform sinus; therefore, fourth branchial cleft cysts arise in various locations, including the thyroid gland and the mediastinum. [21]

Imaging modalities

Both CT scanning and MRI are useful in the evaluation of branchial cleft cysts. The diagnosis of branchial cleft cysts is based primarily on the location of the lesion. The choice of preferred modality depends heavily on regional preferences, with some institutions favoring MRI and others favoring CT scanning. Advocates of MRI believe that this modality more reliably confirms the cystic nature of the mass and more precisely defines the extent of the lesion and its relationship to surrounding structures. Advocates of CT scanning believe that for most lesions, all clinically relevant information is available as clearly on CT scans as on MRIs but with preferable cost, availability, and ease of imaging. [8, 9, 21, 22]

MRI is most advantageous for type I first branchial cleft cysts and for parapharyngeal masses that may be second branchial cleft cysts. A 10-year comparative study on 157 patients recommended the use of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology in combination with MRI to differentiate branchial cleft cyst from a malignant neoplasm. [23] The relationship of glandular tissue to the mass (eg, fat planes between the parotid gland and a parapharyngeal mass) is important for differential diagnosis and for surgical planning. Branchial cleft cysts have high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. On T1-weighted images, the signal intensity is usually low, but previous infection can provoke proteinaceous debris that increases T1 signal intensity. Uninfected branchial cleft cysts should not enhance on MRI. Infiltration of surrounding tissue may indicate lymphangioma.

Fluoroscopic fistulography or CT fistulography may be used to delineate the course of a branchial cleft sinus or fistula. This can aid in surgical planning and in predicting potential complications from surgery.

Ultrasonography is useful in situations in which CT scanning and MRI are unavailable or in the initial assessment of a neck mass, especially in children. Although ultrasonography can confirm the cystic nature of a mass, it does not adequately evaluate the extent and depth of neck lesions. [2, 22, 24, 25, 26]

Computed Tomography

Contrast-enhanced CT scanning reveals a well-defined, nonenhancing mass of fluid attenuation in a characteristic location. The location depends on which branchial cleft is affected. [27, 28]

First branchial cleft cysts are typically well-circumscribed, fluid-filled, and thin-walled. However, wall thickness may increase with recurrent infections. [29] Type I first branchial cleft cysts appear posterior and inferior to the external auditory canal, with a wide tract inferior to the auditory canal usually a diagnostic sign. [17] Type II first branchial cleft cysts appear near the angle of the mandible (see the image below). An analysis of a small sample showed that type II cysts may be more likely to be deep to the facial nerve. [19]

First branchial cleft cyst, type II. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals an ill-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) posterior to the right submandibular gland (g).

First branchial cleft cyst, type II. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals an ill-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) posterior to the right submandibular gland (g).

Second branchial cleft cysts, which are by far the most common, appear immediately anterior to the upper third of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (see the image below).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) on the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) on the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the right neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterolateral to the submandibular gland (g).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the right neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterolateral to the submandibular gland (g).

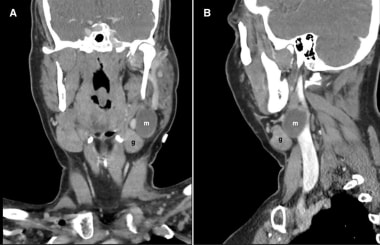

Second branchial cleft cyst. Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) plane reformats from a contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the left neck characteristically posterosuperior to the submandibular gland (g).

Second branchial cleft cyst. Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) plane reformats from a contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the left neck characteristically posterosuperior to the submandibular gland (g).

Third branchial cleft cysts lie beneath or posterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, within the posterior triangle of the neck (see the image below).

Third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the thyroid cartilage reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

Third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the thyroid cartilage reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

Fourth branchial cleft cysts, which are exceedingly rare, may be located in the larynx, in the thyroid gland, in the mediastinum, or along the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Degree of confidence

Both CT scanning and MRI may be unable to distinguish a branchial cleft cyst from a lymphangioma in children (see the image below). In adults, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma to cervical nodes may mimic a branchial cleft cyst.

Cystic hygroma, dermoid cyst, glomus tumor of the head and neck, lipoma, liposarcoma, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, and vascular anomalies are included in the differential diagnosis. Other conditions to be considered include metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, glandular cyst, lymphadenopathy, dermoid tumor of the neck, ranula, laryngocele, thyroglossal duct cyst, and hemangioma of soft tissue.

Multislice spiral CT thin-slice images combined with multiplanar reconstruction and image postprocessing technology can better display the location of branchial cysts and the course of branchial fistulas. [30]

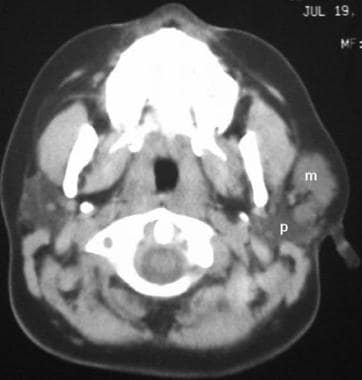

Lymphangiomas (more properly termed "lymphatic malformations") are cystic masses that most often arise in the posterior triangle of the neck; however, these lesions can appear anywhere in the body and can be difficult to distinguish from branchial cleft cysts (see the image below). Branchial cleft cysts are usually well defined and round, whereas lymphangiomas may be infiltrative. Both lesions are treated with surgical excision. On cross-sectional CT imaging, a branchial cleft cyst can be confused most easily with a lymphangioma.

Lymphangioma mimicking a type I first branchial cleft cyst. Nonenhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the parotid glands reveals an ill-defined water attenuation mass (m) immediately anterior to the left parotid gland (p).

Lymphangioma mimicking a type I first branchial cleft cyst. Nonenhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the parotid glands reveals an ill-defined water attenuation mass (m) immediately anterior to the left parotid gland (p).

Glandular cysts, including thymic and parathyroid cysts, are within the spectrum of branchial anomalies. Branchial cleft cysts may involve nearby glandular structures (see the image below); however, thyroid cysts are more likely to result from degenerated adenomas.

A patient who presents with an abscess of the thyroid gland probably has an underlying branchial cleft sinus or fistula communicating with the pyriform sinus.

Intraglandular extension of the third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the cricoid cartilage reveals an ill-defined water-attenuation mass (m) within the right lobe of the thyroid gland. Note the third branchial cleft cyst (c) lateral to the thyroid gland and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

Intraglandular extension of the third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the cricoid cartilage reveals an ill-defined water-attenuation mass (m) within the right lobe of the thyroid gland. Note the third branchial cleft cyst (c) lateral to the thyroid gland and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

Neoplastic or inflammatory lymphadenopathy can have a clinical and radiographic appearance similar to that of branchial cleft cysts. Cystic metastasis (eg, papillary thyroid carcinoma), necrotic metastasis (eg, squamous cell carcinoma), and tuberculous lymphadenitis can result in low-attenuating lymph nodes. In patients with AIDS, mycobacterial infections (eg, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare [MAI], Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex [MAC]) often manifest with cystic cervical nodes. Lymphoma is unlikely to demonstrate cystic degeneration.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can be used to distinguish benign masses from malignant masses, but this modality is notoriously inaccurate in the setting of predominantly cystic metastases.

Regarding ranulas, lingual salivary gland dilatation may result in a cystic mass extending from the oral cavity through the mylohyoid muscle into the submandibular triangle (ie, a plunging ranula). A plunging ranula may mimic a type II first branchial cleft cyst.

Dermoid cysts arise in the midline; this feature distinguishes them from branchial cleft cysts. Dermoid cysts generally have low attenuation because of their fat content.

Laryngocele should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a third or fourth branchial cyst arising in the larynx. Both lesions may have thin or imperceptible walls, usually contain simple fluid, and appear on the lateral aspect of the larynx.

Suprahyoid thyroglossal duct cysts lie in the midline. Infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cysts may be off the midline but usually are not as lateral as branchial cleft cysts.

Lipomas have lower attenuation than cysts on CT scans. Liposarcomas of the neck have a variable appearance, but these lesions are rare.

Hemangiomas (venous malformations) often form mixed tumors with lymphangiomas and can appear anywhere in the neck. Hemangiomas show contrast CT scan enhancement, particularly on delayed images; in this way, they can be distinguished from branchial cleft cysts.

The vascularity of paragangliomas makes them easy to distinguish from branchial cleft cysts on CT; however, these entities may be difficult to distinguish clinically.

Branchial cleft cysts are common causes of cervical tumors in children and adults; prenatal diagnosis is rare. In neonates, these cysts can suddenly increase in size, causing airway obstruction and leading to a life-threatening condition. [31]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI may reveal a hypointense or hyperintense lesion depending on the protein content of the cyst on T1-weighted images. [32] Branchial cleft cysts are usually hyperintense on T2A sequences. [32]

Inflammation surrounding the cyst may thicken its wall and increase peripheral contrast enhancement.

Diffusion-weighted imaging may be useful in delineating a branchial cleft cyst with superimposed infection. Such lesions will demonstrate bright DWI and dark ADC signal intensity, on the basis of infected fluid/pus within the lesion.

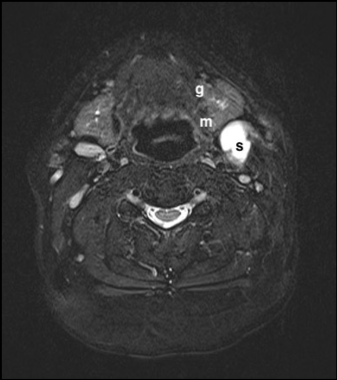

Second Branchial Cleft Cyst. Axial T2 inversion recovery sequence MRI shows a bright cystic mass (m) anteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterior to the submandibular gland, with some mass effect on the gland (g), displacing it anteriorly.

Second Branchial Cleft Cyst. Axial T2 inversion recovery sequence MRI shows a bright cystic mass (m) anteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterior to the submandibular gland, with some mass effect on the gland (g), displacing it anteriorly.

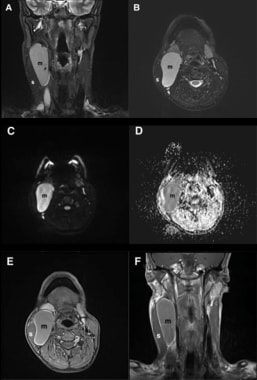

Infected third branchial cleft cyst. Multi-planar MRI reveals a large, well-defined, fluid signal intensity mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein. It is hyperintense on T2 (A, B) as expected. The mass demonstrates diffusion restriction as it is bright on DWI (C) and dark on ADC (D) and shows rim enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration on T1 post-contrast sequences (E and F), consistent with an infected cyst.

Infected third branchial cleft cyst. Multi-planar MRI reveals a large, well-defined, fluid signal intensity mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein. It is hyperintense on T2 (A, B) as expected. The mass demonstrates diffusion restriction as it is bright on DWI (C) and dark on ADC (D) and shows rim enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration on T1 post-contrast sequences (E and F), consistent with an infected cyst.

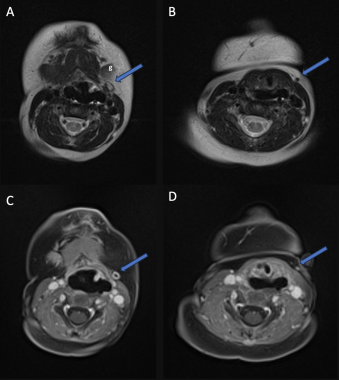

Second branchial fistula. MRI demonstrates a tract (blue arrows), which is bright centrally on T2 and proceeds from the skin of the lateral neck, posterior to the submandibular gland (g). The fistula demonstrates wall enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration (C and D) due to superimposed infection.

Second branchial fistula. MRI demonstrates a tract (blue arrows), which is bright centrally on T2 and proceeds from the skin of the lateral neck, posterior to the submandibular gland (g). The fistula demonstrates wall enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration (C and D) due to superimposed infection.

Ultrasonography

Various imaging modalities have been used to evaluate for the presence of a branchial cleft cyst, as described above. Larger and superficial cystic lesions can be seen on ultrasound, which can help to reveal cystic characteristics. [2]

In the pediatric population, ultrasonography is a valuable modality to visualize cysts as it does not involve radiation or sedation. It can also serve to guide fine needle aspiration in both children and in adults. [23, 33]

Branchial anomalies result from incomplete obliteration of branchial arch structures during embryogenesis. The use of point-of-care ultrasound and understanding the sonographic characteristics of these lesions can greatly assist the physician in their diagnosis. [26]

On sonography, branchial cleft cysts are typically well-defined and anechoic, with posterior acoustic enhancement in 70% of cases. [4, 34] In most cases (82%), branchial cleft cysts are very thin walled. Rarely, infection, hemorrhage, or pseudo-polyp content may also be present. [34]

-

Coronal cross-section of the right side of the neck in a fetus.

-

First branchial cleft cyst, type II. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals an ill-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) posterior to the right submandibular gland (g).

-

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the hyoid bone reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) on the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

-

Third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the thyroid cartilage reveals a large, well-defined, nonenhancing, water attenuation mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

-

Lymphangioma mimicking a type I first branchial cleft cyst. Nonenhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the parotid glands reveals an ill-defined water attenuation mass (m) immediately anterior to the left parotid gland (p).

-

Intraglandular extension of the third branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography scan at the level of the cricoid cartilage reveals an ill-defined water-attenuation mass (m) within the right lobe of the thyroid gland. Note the third branchial cleft cyst (c) lateral to the thyroid gland and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle(s).

-

Second branchial cleft cyst. Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the right neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterolateral to the submandibular gland (g).

-

Second branchial cleft cyst. Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) plane reformats from a contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates a well-marginated nonenhancing water attenuation mass (m) within the left neck characteristically posterosuperior to the submandibular gland (g).

-

Second branchial fistula. MRI demonstrates a tract (blue arrows), which is bright centrally on T2 and proceeds from the skin of the lateral neck, posterior to the submandibular gland (g). The fistula demonstrates wall enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration (C and D) due to superimposed infection.

-

Second Branchial Cleft Cyst. Axial T2 inversion recovery sequence MRI shows a bright cystic mass (m) anteromedial to the sternocleidomastoid muscle (s) and posterior to the submandibular gland, with some mass effect on the gland (g), displacing it anteriorly.

-

Infected third branchial cleft cyst. Multi-planar MRI reveals a large, well-defined, fluid signal intensity mass (m) deep to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (s), medially displacing the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein. It is hyperintense on T2 (A, B) as expected. The mass demonstrates diffusion restriction as it is bright on DWI (C) and dark on ADC (D) and shows rim enhancement following intravenous gadolinium administration on T1 post-contrast sequences (E and F), consistent with an infected cyst.