Practice Essentials

The most common mass in the popliteal fossa, Baker cyst, also termed popliteal cyst, results from fluid distention of the gastrocnemio-semimembranosus bursa, which is located in the medial aspect of the popliteal fossa. [1] The eponym honors the work of Dr William Morrant Baker. In 1877, Baker described 8 cases of periarticular cysts caused by synovial fluid that had escaped from the knee joint and formed a new sac outside the joint. [2] The common underlying conditions were osteoarthritis and Charcot joint. [3, 4]

Baker cysts can be associated with conditions such as osteoarthritis of the knee, meniscal tears, rheumatoid arthritis, Charcot joints, and synovial disorders of the knee. The majority of patients with Baker cysts are asymptomatic, but knee joint pain and stiffness and a palpable mass in the medial popliteal fossa are not uncommon. The manifestations of a ruptured cyst can resemble those of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or thrombophlebitis [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

(See the images below.)

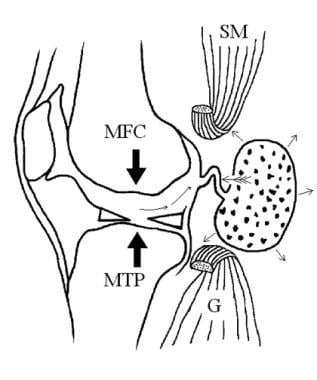

Valvular mechanism of Baker cyst. Effusion and fibrin are pumped (large arrows) into the Baker cyst (long, thin arrows). In the Bunsen-valve mechanism, the enlarging Baker cyst exerts mass effect (feathered arrow) on the slitlike communication between the joint and the cyst, trapping effusion. In the ball-valve mechanism, fibrin serves as a 1-way valve that prevents the effusion's return to the knee joint. Trapped effusion is reabsorbed through the semipermeable membrane (short, thin arrows), leaving behind concentrations of fibrin. (MFC: medial femoral condyle; MTP: medial tibial plateau; G: medial head of gastrocnemius muscle; SM: semimembranosus muscle)

Valvular mechanism of Baker cyst. Effusion and fibrin are pumped (large arrows) into the Baker cyst (long, thin arrows). In the Bunsen-valve mechanism, the enlarging Baker cyst exerts mass effect (feathered arrow) on the slitlike communication between the joint and the cyst, trapping effusion. In the ball-valve mechanism, fibrin serves as a 1-way valve that prevents the effusion's return to the knee joint. Trapped effusion is reabsorbed through the semipermeable membrane (short, thin arrows), leaving behind concentrations of fibrin. (MFC: medial femoral condyle; MTP: medial tibial plateau; G: medial head of gastrocnemius muscle; SM: semimembranosus muscle)

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows uniform joint-space loss in the medial and lateral knee compartments without osteophytosis. A Baker cyst is seen medially (arrowhead).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows uniform joint-space loss in the medial and lateral knee compartments without osteophytosis. A Baker cyst is seen medially (arrowhead).

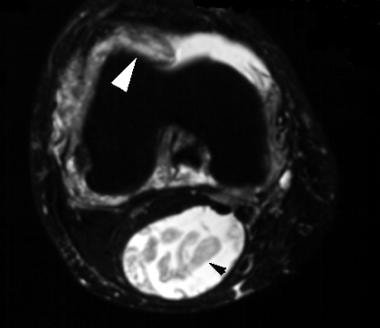

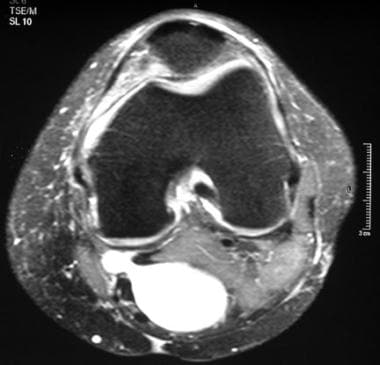

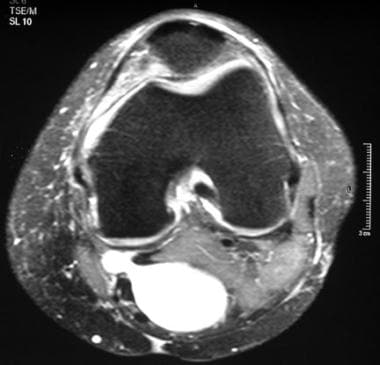

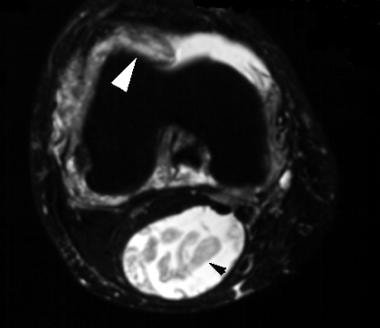

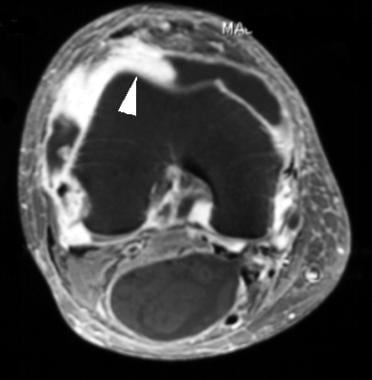

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee shows effusion, synovial proliferation (white arrowhead), and a Baker cyst that contains debris (black arrowhead).

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee shows effusion, synovial proliferation (white arrowhead), and a Baker cyst that contains debris (black arrowhead).

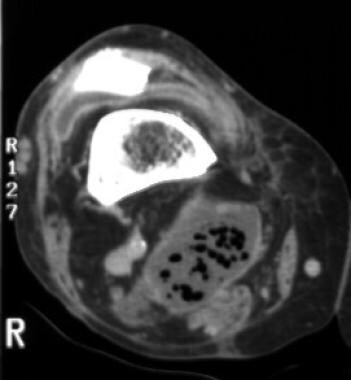

Contrast-enhanced, axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee shows multiple gaslike lucencies within a Baker cyst and synovial enhancement.

Contrast-enhanced, axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee shows multiple gaslike lucencies within a Baker cyst and synovial enhancement.

Differential diagnosis includes the following:

-

Ganglion cyst [1]

-

Meniscal cyst [11]

-

Myxoid liposarcoma

-

Popliteal artery aneurysm [11]

-

Popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm

-

Synovial sarcoma [12]

-

Osteochondrolipoma [13]

-

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [14]

Care must be taken to differentiate ruptured Baker cysts from deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Administration of low-molecular-weight heparin to treat suspected DVT can lead to compartment syndrome in patients with Baker cysts. [15]

Imaging modalities

Plain radiographs are simple and readily available, but they provide limited information about the popliteal cyst. However, they should be obtained early in the evaluation, as they are useful for detecting other conditions commonly found in association with popliteal cysts, such as osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and loose bodies. [11, 1]

In the past, Baker cysts were commonly detected by conventional arthrography, but disadvantages include invasiveness and the use of ionizing radiation. [1, 11] Ultrasound has largely replaced arthrography as the initial assessment for Baker cysts and is an easy-to-use, rapid, relatively inexpensive examination to employ in this setting. [16, 17, 18, 19] Ultrasonography determines whether the popliteal mass is a pure cystic structure or a complex cyst and/or solid mass (see the images below). [11, 20, 21, 22, 23] It allows assessment of the size of the cyst; its relationship to adjacent muscles, tendons, and vessels; and the presence of intracystic loose bodies or septations. In addition, US can differentiate these cysts from popliteal aneurysms and ganglion cysts. [1] The ability to detect Baker cysts is near 100%, but ultrasound lacks the specificity to differentiate Baker cysts from meniscal cysts or myxoid tumors. Another disadvantage is that it does not adequately visualize other conditions in the knee that are often associated with these cysts, such as meniscal tears. [11] On ultrasonography, myxoid liposarcomas appear as complex, hypoechoic masses that do not meet the criteria for a simple cyst. Contrast enhancement is helpful in distinguishing cystic or necrotic lesions from solid cellular lesions.

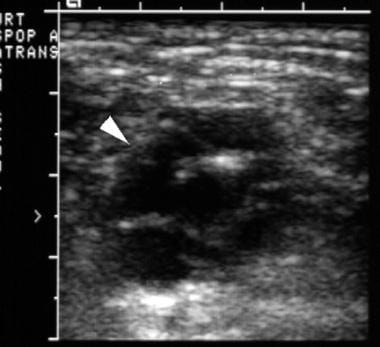

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the knee in a patient who had recent arthroscopy shows a complex, cystic mass (arrow) in the medial aspect of popliteal fossa. The mass communicates with the knee joint (arrowhead), which is consistent with a Baker cyst.

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the knee in a patient who had recent arthroscopy shows a complex, cystic mass (arrow) in the medial aspect of popliteal fossa. The mass communicates with the knee joint (arrowhead), which is consistent with a Baker cyst.

Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a Baker cyst in a patient who underwent recent knee arthroscopy.

Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a Baker cyst in a patient who underwent recent knee arthroscopy.

Chatzopoulos et al found that Baker cysts are a common ultrasonographic finding in knees with chronic osteoarthritic pain and also found that they are associated with synovial inflammation and its grade. Baker cysts were identified in 89 of 328 chronic osteoarthritic knees (27%), but only 1 cyst was found in 54 nonosteoarthritic knees (2%). Abnormal and intense tracer accumulations in early-phase bone scintigraphy were also significantly more frequent in osteoarthritic knees with Baker cysts than in those without Baker cysts. [24]

Color Doppler imaging can confirm the absence of vascular flow within the mass to exclude a popliteal artery aneurysm or cystic adventitial degeneration of a popliteal artery (see the images below). [20] Ultrasonography can concomitantly exclude a coexisting deep venous thrombosis (DVT) created by subjacent mass effect. The weakness of ultrasonography is related to the difficulty in establishing a true connection to the joint space proper, which is essential for discriminating between a Baker cyst from other potentially harmful conditions.

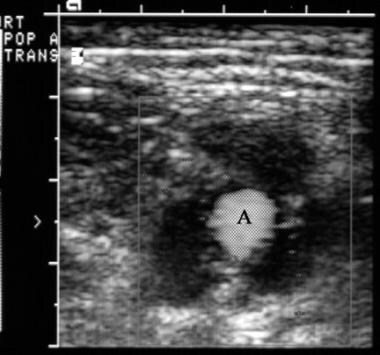

Transverse color Doppler ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows multiple cysts surrounding a normal-sized popliteal artery (A), which is consistent with cystic adventitial degeneration.

Transverse color Doppler ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows multiple cysts surrounding a normal-sized popliteal artery (A), which is consistent with cystic adventitial degeneration.

The communication with the joint by way of the gastrocnemio-semimembranosus bursa is deep within the popliteal space, adjacent to the dense posterior femoral cortex. The ultrasonography probe is placed over the popliteal skin surface, and because this thin, necklike connection to the joint is anterior to the cyst, the mere presence of a large or complex Baker cyst may obscure the visualization of this connection.

CT scanning can delineate a low-to-intermediate attenuation mass, which normally measures from 20 to -10 Hounsfield units, in the posteromedial popliteal space. CT scanning can easily delineate secondary findings, such as intracystic osseous fragments, mass effect, wall thickening, and bony erosion.

Magnetic resonance imaging is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of Baker cysts and for differentiating them from other conditions. Its main disadvantage is the high cost; therefore, ultrasound should be considered as a screening modality if evaluation of the intra-articular structures is not necessary. In current radiologic practice, Baker cysts are often detected on MRI evaluations of the knee (performed for any indication). The advantages of MRI are derived from the superior soft-tissue contrast resolution that it affords and from the modality's multiplanar capability, which help determine the extent and composition of the Baker cyst. It allows assessment of the entire spectrum of related disorders, such as meniscal tears, chondral defects, loose bodies, synovitis, osteoarthritis, and ligament tears. Conditions such as meniscal cysts are more easily differentiated from Baker cysts with MRI than ultrasound. [11]

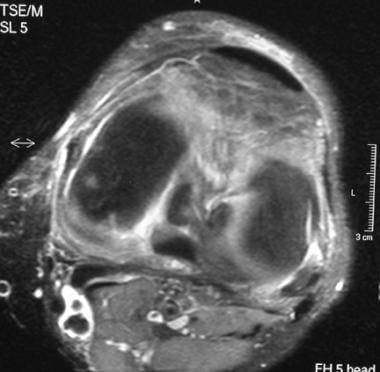

One of the most important benefits of employing MRI is the ability to use the axial plane to establish positive identification of the high-signal intensity, fluid-filled neck of the cyst that connects the cyst to the joint space (see the image below). This makes it possible to discriminate between a benign Baker cyst and one of the uncommon, but clinically important, types of cystic tumors, such as myxoid liposarcoma, that can occur in the popliteal fossa.

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation reveals a Baker cyst connected to the knee joint by way of a narrow neck between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles.

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation reveals a Baker cyst connected to the knee joint by way of a narrow neck between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles.

Guerra and colleagues found a 30% incidence of popliteal bursa in cadaveric anatomic dissection of older patients. [25] Using diagnostic arthroscopy, Johnson and coauthors demonstrated a 37% incidence of popliteal bursa. [26] The incidence of Baker cysts detected through MRI of the knee varies (5-18%) according to the patient population. Initially, Fielding and colleagues reported an association between Baker cyst and tear of the medial meniscus or complete tear of the ACL. [27] Stone and colleagues demonstrated that 84% of Baker cysts detected on magnetic resonance images had meniscal tears. Most tears were observed in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. [28]

Miller and coauthors confirmed a significant association of Baker cyst with effusion, meniscal tears, and degenerative arthropathy. [29] The probability of a Baker cyst in the presence of any 1 variable (ie, association) is as follows: P=0.08-0.10; of any 2 variables, P=0.19-0.21; and of all 3 variables, P=0.38. However, no association was found between Baker cyst and ACL tear.

Radiography

Imaging evaluation of a popliteal mass begins with conventional radiography to detect a soft-tissue mass, calcifications, and bony involvement. A Baker cyst appears as a soft-tissue mass in the posteromedial knee joint. [30] Occasionally, a Baker cyst is suggested by the presence of multiple, calcified loose bodies in the cyst (see the images below).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows calcifications (arrowhead) overlying the medial tibial plateau.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows calcifications (arrowhead) overlying the medial tibial plateau.

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows multiple calcified bodies (arrowhead) posterior to the knee, which is consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis.

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows multiple calcified bodies (arrowhead) posterior to the knee, which is consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis.

Rarely, a solitary loose body in a Baker cyst may mimic a fabella on a lateral radiograph of the knee (see the image below).

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows a calcified body (arrowhead), which appears to be a large fabella, posterior to the knee.

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows a calcified body (arrowhead), which appears to be a large fabella, posterior to the knee.

However, on a frontal radiograph (see the image below), the calcified body in the Baker cyst will be located behind the medial femoral condyle, whereas a fabella will be present behind the lateral femoral condyle.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows that a calcified body (arrowhead) is overlying the medial femoral condyle, making a fabella highly unlikely. The calcified, loose body is in a Baker cyst.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows that a calcified body (arrowhead) is overlying the medial femoral condyle, making a fabella highly unlikely. The calcified, loose body is in a Baker cyst.

Jayson and Dixon studied the valvular mechanisms in juxta-articular cysts and postulated that joint effusion and fibrin are pumped from the knee joint into the Baker cyst but—because of a valvelike communication (either a Bunsen or ball valve)—not in the reverse direction. [31] The effusion can be readily reabsorbed through the synovial membrane, leaving behind concentrations of fibrin, which on radiographs may appear as gaslike lucencies.

A noninfected Baker cyst with gaslike lucencies (see the images below) may occur along with diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Because gaslike lucencies in a Baker cyst are rare and an infected Baker cyst is a serious condition, the former diagnosis must be one of exclusion; a CT scan with appropriate window settings allows discrimination between air and fibrin.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows multiple tiny lucencies superior to the medial femoral condyle (arrowhead).

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows multiple tiny lucencies superior to the medial femoral condyle (arrowhead).

Computed Tomography

On a CT scan, a Baker cyst appears as a fluid-containing mass located behind the medial femoral condyle and between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles. A space-occupying lesion in the posteromedial knee suggests the diagnosis but is not always sufficient to exclude other etiologies, for which MRI or ultrasonography is more specific.

CT scanning is not as sensitive as MRI in detecting an internal derangement, which may be the cause of a Baker cyst. In addition, the definitive diagnosis of a Baker cyst may not be made without the injection of air and/or iodinated contrast material into the knee joint (see the image below).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

On MRI, a Baker cyst appears as a homogeneous, high-signal intensity, cystic mass behind the medial femoral condyle; a thin, fluid-filled neck interdigitates between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles (see the image below). [21, 27, 29, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation reveals a Baker cyst connected to the knee joint by way of a narrow neck between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles.

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation reveals a Baker cyst connected to the knee joint by way of a narrow neck between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles.

An uncomplicated Baker cyst should demonstrate homogeneous high-signal intensity on all fluid-sensitive pulse sequences, including on the second echo of a conventional or fast/turbo spin-echo sequence, on short tau inversion recovery (STIR), or on gradient echo (GRE)/fast field echo (FFE) sequences employing a low flip angle (10-30º). The axial plane (see the previous image) allows the cyst, neck, and joint space to be seen in contiguity, although the cyst may be demonstrated in all 3 planes.

In addition, intravenously administered gadolinium can detect synovial enhancement (see the images below) and pannus formation in RA in the cyst and in the joint space proper, prior to the radiographic detection of well-known signs of RA much later in the course of the disease (erosion, uniform joint space loss without marked osteophytosis, periarticular osteopenia, soft-tissue swelling).

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee shows effusion, synovial proliferation (white arrowhead), and a Baker cyst that contains debris (black arrowhead).

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee shows effusion, synovial proliferation (white arrowhead), and a Baker cyst that contains debris (black arrowhead).

Axial, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee after the intravenous administration of gadolinium shows synovial enhancement (arrowhead).

Axial, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee after the intravenous administration of gadolinium shows synovial enhancement (arrowhead).

Off-label usage of intra-articular gadolinium in magnetic resonance arthrography, now common in establishing the presence of a meniscal retear, is perhaps the most vivid way to display a Baker cyst. MRI can also detect underlying internal derangements of the knee (see the images below), which may be etiologic in the formation of a Baker cyst.

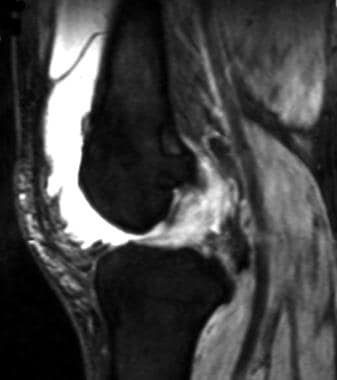

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee shows a large knee effusion and a Baker cyst.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee shows a large knee effusion and a Baker cyst.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee, lateral to the view in Image above, shows a complete rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee, lateral to the view in Image above, shows a complete rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.

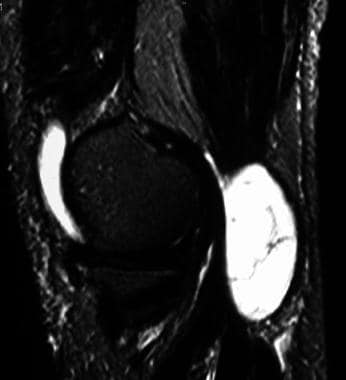

In a complex Baker cyst, calcified loose bodies can be detected; these appear on fluid-sensitive images as low-signal intensity, rounded foci within high-signal intensity, cystic fluid (see the images below).

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a complicated Baker cyst containing multiple internal septations.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a complicated Baker cyst containing multiple internal septations.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

Sansone and colleagues reviewed the incidence of associated intra-articular disorders in a series of 1001 adult patients undergoing MRI of the knee and found that the most common associated lesions were meniscal tears, chondral lesions, and ACL tears. [32]

Gadolinium-based contrast agents have been linked to the development of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) or nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy (NFD). The disease has occurred in patients with moderate to end-stage renal disease after being given a gadolinium-based contrast agent to enhance MRI or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) scans. NSF/NFD is a debilitating and sometimes fatal disease. Characteristics include red or dark patches on the skin; burning, itching, swelling, hardening, and tightening of the skin; yellow spots on the whites of the eyes; joint stiffness with trouble moving or straightening the arms, hands, legs, or feet; pain deep in the hip bones or ribs; and muscle weakness.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is a very helpful imaging technique in the evaluation of a popliteal mass. [37, 38, 39, 22, 40, 41, 42] The modality can be used to determine whether the popliteal mass is a cyst or a solid mass. A simple Baker cyst appears as an anechoic mass with posterior acoustic enhancement that communicates with the knee joint. Findings on an ultrasonogram relate to the criteria of a simple cyst, which include an anechoic mass, a sharply defined posterior wall, and posterior acoustic enhancement. A complex Baker cyst has internal echoes within the hypoechoic mass (see the images below).

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the knee in a patient who had recent arthroscopy shows a complex, cystic mass (arrow) in the medial aspect of popliteal fossa. The mass communicates with the knee joint (arrowhead), which is consistent with a Baker cyst.

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the knee in a patient who had recent arthroscopy shows a complex, cystic mass (arrow) in the medial aspect of popliteal fossa. The mass communicates with the knee joint (arrowhead), which is consistent with a Baker cyst.

Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a Baker cyst in a patient who underwent recent knee arthroscopy.

Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a Baker cyst in a patient who underwent recent knee arthroscopy.

Calcified loose bodies within a Baker cyst appear as mobile, intraluminal, echogenic foci with distal acoustic shadowing, an appearance similar to that of cholelithiasis in a gallbladder. An additional advantage of ultrasonography is that it can exclude a coexisting DVT.

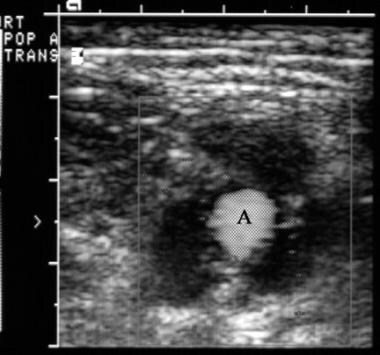

Color Doppler ultrasonography can detect vascular flow within the mass to exclude a popliteal artery aneurysm. In cystic adventitial degeneration of the popliteal artery, ultrasonographic examination reveals multiple cystic structures surrounding a normal-sized artery (see the images below). This is the fastest, most cost-effective manner in which to diagnose a Baker cyst.

Transverse color Doppler ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows multiple cysts surrounding a normal-sized popliteal artery (A), which is consistent with cystic adventitial degeneration.

Transverse color Doppler ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows multiple cysts surrounding a normal-sized popliteal artery (A), which is consistent with cystic adventitial degeneration.

A cyst that is too large or complex may obscure visualization of the fluid-filled connection to the joint space proper, leading to a false-positive diagnosis.

Arthritis is the most common condition associated with Baker cysts, with osteoarthritis probably being the most frequent cause among the arthritides. [24] Although the prevalence of Baker cysts in patients with inflammatory arthritis is higher than in patients with osteoarthritis, osteoarthritis is much more common than inflammatory arthritis. Using ultrasonography, Fam and colleagues found that 21 of 50 patients (42%) with osteoarthritis had Baker cysts. [37] Bilateral cysts were seen in 8 patients (16%). The occurrence of Baker cysts relates directly to the presence of knee effusion and the severity of the osteoarthritis.

In 99 consecutive patients with RA, Andonopoulos and coauthors demonstrated Baker cysts on ultrasonograms of 47 patients (48%). [38] Twenty of the 99 patients (20%) had bilateral cysts. Of 198 knees, 67 (34%) had Baker cysts, yet only 29 cysts (43%) were diagnosed clinically. Baker cysts appear much less frequently in children than in adults. The prevalence of Baker cysts in asymptomatic children examined ultrasonographically was 2.4%. The prevalence of Baker cyst in children undergoing MRI examination of the knee was 6.3%. None of the children with Baker cyst demonstrated an associated ACL or meniscal tear. Four patients (8%) had osteochondritis dissecans (N = 2), septic arthritis (N = 1), or juvenile RA (n = 1). In most children with Baker cysts (82%), the cysts disappeared without intervention (84%) or caused no symptoms (16%). However, in children with arthritis, Baker cysts are common.

In a study of 44 children with knee arthritis, ultrasonography detected a Baker cyst in 27 children (61%), most of whom (80%) had juvenile RA. [39] The remaining causes of arthritis in the study included spondyloarthropathy, psoriatic arthritis, septic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Cysts were followed prospectively with serial ultrasonography for 18-24 months. Cysts resolved with the resolution of suprapatellar effusion. Reports of Baker cyst associated with gout, Reiter syndrome, psoriasis, and systemic lupus erythematosus exist. The common underlying pathology for these medical conditions is synovial proliferation with effusion.

In a study by Stroiescu et al of image-guided aspiration followed by therapeutic injection for symptomatic Baker cysts, ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance followed by therapeutic injection of methylprednisolone acetate and bupivacaine was shown to provide durable reduction in pain symptoms in the majority of patients. [5]

In a meta-analysis of 13 studies (1011 patients) regarding the use of ultrasonography to diagnose Baker cyst, sensitivity and specificity were 0.97 and 1.00, respectively, compared to pathology. [16]

-

Valvular mechanism of Baker cyst. Effusion and fibrin are pumped (large arrows) into the Baker cyst (long, thin arrows). In the Bunsen-valve mechanism, the enlarging Baker cyst exerts mass effect (feathered arrow) on the slitlike communication between the joint and the cyst, trapping effusion. In the ball-valve mechanism, fibrin serves as a 1-way valve that prevents the effusion's return to the knee joint. Trapped effusion is reabsorbed through the semipermeable membrane (short, thin arrows), leaving behind concentrations of fibrin. (MFC: medial femoral condyle; MTP: medial tibial plateau; G: medial head of gastrocnemius muscle; SM: semimembranosus muscle)

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows uniform joint-space loss in the medial and lateral knee compartments without osteophytosis. A Baker cyst is seen medially (arrowhead).

-

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the knee in a patient who had recent arthroscopy shows a complex, cystic mass (arrow) in the medial aspect of popliteal fossa. The mass communicates with the knee joint (arrowhead), which is consistent with a Baker cyst.

-

Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of a Baker cyst in a patient who underwent recent knee arthroscopy.

-

Transverse ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows a complex, cystic mass (arrowhead).

-

Transverse color Doppler ultrasonographic image of the popliteal fossa shows multiple cysts surrounding a normal-sized popliteal artery (A), which is consistent with cystic adventitial degeneration.

-

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation reveals a Baker cyst connected to the knee joint by way of a narrow neck between the tendons of the medial head of the gastrocnemius and semimembranosus muscles.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows calcifications (arrowhead) overlying the medial tibial plateau.

-

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows multiple calcified bodies (arrowhead) posterior to the knee, which is consistent with synovial osteochondromatosis.

-

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows a calcified body (arrowhead), which appears to be a large fabella, posterior to the knee.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows that a calcified body (arrowhead) is overlying the medial femoral condyle, making a fabella highly unlikely. The calcified, loose body is in a Baker cyst.

-

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee shows effusion, synovial proliferation (white arrowhead), and a Baker cyst that contains debris (black arrowhead).

-

Axial, T1-weighted magnetic resonance image of the knee after the intravenous administration of gadolinium shows synovial enhancement (arrowhead).

-

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee shows a large knee effusion and a Baker cyst.

-

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation of the knee, lateral to the view in Image above, shows a complete rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament.

-

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a complicated Baker cyst containing multiple internal septations.

-

Sagittal, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

-

Axial, T2-weighted magnetic resonance image with fat saturation shows a Baker cyst containing hypointense, loose bodies.

-

Arthrography of the knee performed prior to radioactive synoviorthesis shows leakage of contrast (arrow) just superior to the sinus (arrowhead and "BB" marker).

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows multiple tiny lucencies superior to the medial femoral condyle (arrowhead).

-

Lateral radiograph of the knee shows multiple tiny lucencies (arrowhead) posterior to the knee.

-

Contrast-enhanced, axial computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee shows multiple gaslike lucencies within a Baker cyst and synovial enhancement.