Practice Essentials

Psoriatic arthritis (PA) is a specific type of arthritis that has been diagnosed in approximately 23% of those who have psoriasis. [1] PA can occur in any age group; however, in most patients, it manifests itself between 30 and 50 years of age. On average, PA appears about 10 years after the first signs of psoriasis occur, but in about 1 of 7 people with PA, arthritis symptoms occur before any skin lesions appear. Most patients with PA also have psoriasis; patients rarely have PA without psoriasis.

A haplotype epidemiologic association with PA involves the expression of both class I and class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, including HLA-B13, HLA-B17, HLA-B27, HLA-B38, HLA-B39, HLA-Cw6, HLA-DR4, and HLA-DR7. HLA-B27 is present in 60% of individuals with the disease, as compared with 8% of the general population.

Dactylitis, which is associated with more erosive forms of PA, is often the initial feature of PA and may be the only feature for months to years. [2]

Guidelines on psoriatic arthritis have been published by organizations such as the American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation, European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the British Society of Rheumatology (BSR), and the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). [11, 3, 4, 5]

Types of PA

Five types of PA have been defined; these types can coexist, but they tend to occur separately in most cases:

-

Arthritis involving primarily the small joints of the fingers or toes (asymmetrical oligoarthritis) — 55-70%

-

Asymmetrical arthritis, which involves the joints of the extremities — 30-50%

-

Symmetrical polyarthritis, which resembles RA — 15-70%

-

Arthritis mutilans, which is a rare but deforming and destructive condition — 3-5%

-

Arthritis of the sacroiliac joints and spine (psoriatic spondylitis) — 5-33%.

Preferred examination

PA is diagnosed and assessed with radiography, which is the cornerstone in assessing and monitoring inflammatory arthritides such as PA. Radiographic findings are reproducible and allow for the serial monitoring of patients. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive, the cost of this modality makes it a second-line means for monitoring patients with PA. [6, 7, 8, 9] [10, 11]

Ultrasound has played a role because of its lack of radiation exposure and easy accessibility. This technique is more sensitive and specific than clinical examination in detecting active synovitis, and the identification of specific synovitis patterns enables differentiation of PA from RA and other entities. [12]

The Andersson lesion (erosive discovertebral lesion) can be the initial sign of pathology in axial PA. [13]

Prognosis

Early recognition and treatment are likely to result in better long-term outcomes. Delay in diagnoses of 6 and 12 months have been shown to impact on long-term joint damage and functional disability. [14]

Factors that portend a worse prognosis for patients with PA include the following:

-

A strong family history of psoriasis

-

Disease onset younger than age 20 years

-

Expression of HLA-B27, HLA-Cw6, or HLA-DR4 alleles

-

Polyarticular disease

-

Erosive disease

-

Extensive skin involvement

In addition, 40% of PA patients fulfill the diagnosis for metabolic syndrome, which contributes to an increased cardiovascular risk. Effective management of metabolic syndrome is key to minimizing morbidity and mortality. [14]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis of the hands and spine. Enteropathic arthritis (arthritis of inflammatory bowel disease) should also be considered, and spotted bone disease has been reported in a patient with psoriatic arthritis. [15, 16, 2]

Patient education

For patient education resources, see the Skin Conditions & Beauty Center, as well as Types of Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and Psoriasis Medications.

Radiography

Plain radiography is the main imaging modality for assessing PA, although early in PA, there may be no radiographic findings. Soft tissue swelling often precedes osseous findings. [7, 17, 10, 11]

Hands and feet

Findings of PA of the hands and feet include the following:

-

No or minimal juxta-articular osteoporosis: In RA, this is more prominent.

-

Bony proliferation near joints and ligament and/or tendon insertion sites (ie, entheses): Enthesis sites include the calcaneus, ischial tuberosities, femoral trochanters, ankle malleoli, anterior patella, ulnar olecranon, and condyles of the distal femur and proximal tibia. This is not a feature of RA.

-

Bone erosion beginning in the periarticular region and progressing to more central areas.

-

Asymmetrical destruction of the DIP with bony ankylosis: RA affects the metacarpal phalangeal joint and proximal interphalangeal joint [PIP] to a greater extent.

-

Resorption of terminal phalangeal tufts (ie, the morning-star appearance)

-

Osteolysis of the bone with telescoping of the digits (ie, the pencil-in-cup deformity)

-

Periostitis along the shaft of a bone, often accompanied by soft tissue swelling

-

Ivory phalanx

-

Destruction/resorption of the interphalangeal joint of the first toe, with periosteal reaction and bony proliferation at the distal phalangeal base: This finding is highly suggestive of PA.

-

Diffuse soft tissue swelling of an entire digit (ie, sausage digit)

-

General symmetrical joint involvement

Charcot-like arthropathy is a newly recognized subset of PA. [18]

In the paper “Predictors for radiological damage in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single centre,” Bond et al concluded that the number of actively inflamed joints — specifically, the number of swollen joints — could be predictive of damage progression, as visualized radiologically. [19] A higher risk of damage progression was related to a higher number of previously inflamed and damaged joints.

Spine

Findings of PA of the spine include the following:

-

Asymmetrical paravertebral ossification from the lower thoracic spine to the upper lumbar spine: This may be vertically directed and may not always be attached to the vertical margins, as in ankylosing spondylitis.

-

Bony proliferation along anterior cervical spine and apophyseal joint-space narrowing.

-

Squaring of the lumbar vertebrae in L-spine: This occurs in ankylosing spondylitis but is uncommon in PA.

-

Paravertebral soft tissue calcifications

-

Synovitis: This may cause atlantoaxial subluxation in a few patients.

Sacroiliac joints

Findings of PA of the sacroiliac joints include the following:

-

Bilateral, often asymmetrical, sacroiliitis.

-

Marginal erosions

-

Widening of the joint margin and sclerosis: This is less common in PA than in ankylosing spondylitis.

Other sites

Findings of PA of other sites include the following:

-

Erosions in the temporomandibular joints

-

Sternal synchondrosis

Achilles tendon

Ozcakar et al noted that patients with PA had thicker tendon measurements than the control group and that those patients with radiologically proven enthesopathy had even thicker tendon measurements. [20]

Mullan et al noted that early changes in serum type II collagen biomarkers predicted radiographic progression at 1 year in patients with inflammatory PA after biologic treatments. [21]

(See the radiographic images below.)

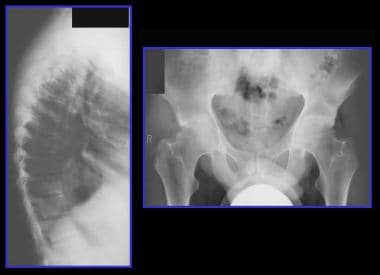

Anteroposterior radiograph of the abdomen shows fusion of the sacroiliac joints. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the abdomen shows fusion of the sacroiliac joints. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

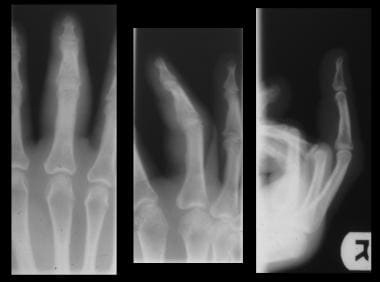

Anteroposterior radiograph of the hands shows subchondral erosions of the fourth left distal interphalangeal joint and right third and fourth proximal interphalangeal joints with periosteal reaction. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the hands shows subchondral erosions of the fourth left distal interphalangeal joint and right third and fourth proximal interphalangeal joints with periosteal reaction. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the feet shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the feet shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the thumb shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the thumb shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis in a male patient shows sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis in a male patient shows sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Left, lateral radiograph of the dorsal spine of a 38-year-old man shows spondylitis in association with psoriasis. Note the squaring of the anterior vertebral bodies. Right, radiograph of the pelvis in the same patient shows sacroiliitis and erosive changes around both hip joints. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Left, lateral radiograph of the dorsal spine of a 38-year-old man shows spondylitis in association with psoriasis. Note the squaring of the anterior vertebral bodies. Right, radiograph of the pelvis in the same patient shows sacroiliitis and erosive changes around both hip joints. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Radiograph views of the fourth finger show diffuse soft tissue swelling. This is a nonspecific finding and can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus, Reuter syndrome, gout, and infection. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.

Radiograph views of the fourth finger show diffuse soft tissue swelling. This is a nonspecific finding and can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus, Reuter syndrome, gout, and infection. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.

Radiograph showing extensive bony destruction around the interphalangeal joint of the second toe. There is associated widening of the joint space, which helps distinguish this condition from osteoarthritis. The base of the middle phalanx is expanded, and there is diffuse soft-tissue swelling but no osteoporosis. Marked osseous erosion about the joint has produced a characteristic pencil-in-cup deformity. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.

Radiograph showing extensive bony destruction around the interphalangeal joint of the second toe. There is associated widening of the joint space, which helps distinguish this condition from osteoarthritis. The base of the middle phalanx is expanded, and there is diffuse soft-tissue swelling but no osteoporosis. Marked osseous erosion about the joint has produced a characteristic pencil-in-cup deformity. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.

Differential diagnosis

A pattern of predominant DIP involvement can distinguish PA from RA. In the axial skeleton, cervical spinal involvement can be prominent in RA, but thoracic and lumbar changes are unusual. Sacroiliac involvement is a minor feature of RA, but large joints are more involved in RA than in PA.

Differentiating PA from RA can be difficult; however, the following may aid in the diagnostic effort:

-

PA maintains bone mineralization and has periosteal reaction and new-bone formation.

-

PA is RF negative, whereas RA is RF positive.

-

PA does not manifest with rheumatoid nodules.

-

Sausage digit and spontaneous joint fusion are common in PA and Reiter syndrome but not in RA.

A study by Sandobal et al suggested that ultrasound helps distinguish RA from PA because of differences in the ventral nail plate. [22] Sandobal et al found significant differences, measured by ultrasound (P< 0.0001), of the mean distance ventral plate-osseous margin of the distal phalanx in psoriatic arthritis patients (P=0.001), in patients with cutaneous psoriasis (P=0.005), and in rheumatoid arthritis patients (P=0.548).

Whole-body MRI can also be used to distinguish RA from PA. [23, 24]

The distinction between PA and other seronegative spondyloarthropathies is largely made on the basis of distribution. PA involves both the upper and lower extremities, whereas Reiter syndrome predominantly involves the lower extremities.

Ankylosing spondylitis causes changes mainly in the axial skeleton, with bilateral and symmetrical changes being the rule. The spinal bony excrescences of PA and Reiter syndrome are larger and broader than the typical thin, linear syndesmophytes of ankylosing spondylitis.

An entity often grouped with psoriasis is pustulosis palmaris et plantaris, or PPP. Mejjad et al reported that PPP and PA can be distinguished radiologically. [25] They found that the anterior chest wall, especially the sternocostoclavicular joints, is more frequently involved in pustulotic arthritis than in psoriasis, both clinically and radiologically. Sternocostoclavicular joints generally appeared with erosive lesions in psoriasis but with large ossifications in PPP. In PA, peripheral joint involvement was more often erosive (43% vs 8%). The frequency rates of sacroiliitis and spinal involvement were similar in PPP and psoriasis. Biologic features and bone scans did not help distinguish between these 2 conditions. Mejjad et al also found that peripheral joint involvement may be monoarticular or oligoarticular and may affect the proximal joints in PPP (74% vs 21%), or it may be polyarticular and involve small distal joints in psoriasis (60% vs 0%). [25]

Computed Tomography

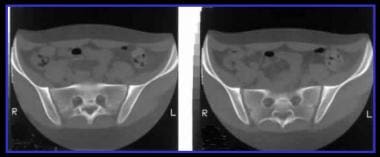

Although plain radiography is the primary modality in assessing PA, computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard for evaluating bone changes in arthritis and can provide further information about the extent and severity of disease. [17] This is particularly true in areas that are difficult to evaluate with radiographs, such as the sacroiliac joint, the temporomandibular joint, and the sternum/manubrium.

CT scanning is particularly useful in identifying inflammatory lesions, even when preexisting degenerative disease is present; in demonstrating the articular surfaces of bone in an exact fashion; and, in some cases of sacroiliitis, in clearly demonstrating erosive changes that can appear equivocal or negative on radiography.

The drawbacks of CT are that it is unable to detect active inflammatory lesions and involves ionizing radiation [17] .

(See the CT image of PA below.)

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the pelvis in a male patient with sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. The CT scans show subtle changes of sacroiliitis more clearly than do conventional radiographs. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the pelvis in a male patient with sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. The CT scans show subtle changes of sacroiliitis more clearly than do conventional radiographs. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

Furthermore, CT scans may demonstrate a variety of findings in PA, including right sternal bone sclerosis with surrounding subchondral erosion and a clavicular bone sclerosis, and can show bilateral clavicular osteophytes and discrete surrounding subchondral cysts and erosions. [26]

In one study, the distal interphalangeal (DIP) finger joints were compared in 6 patients using radiograph-aided 3D diffuse optical tomography: 2 patients with osteoarthritis, 2 with psoriatic arthritis, and 2 normal controls. Researchers scanned the DIP joints using the multimodality imaging method and found that psoriatic arthritis could be distinguished from osteoarthritis. The authors concluded that the fused imaging technique might be useful in distinguishing the significant differences between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. [27]

Dual-Energy CT (CT that utilizes 2 energy levels instead of 1 to examine the differing attenuation properties of matter) has also been suggested as a valuable imaging method to identifty inflammatory lesions of hand PA. [28]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging method, allowing for detection of enthesitis, dactylitis, synovitis, erosions, and bone marrow edema even before changes are visible on radiographs [29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] ; however, because it may not be widely available and because of its cost, it is mostly utilized in cases where inflammation is suspected and radiographs are not helpful or as an accessory tool to determine treatment modifications. [35, 36]

Offidani et al compared the use of MRI with the use of standard radiographs in the evaluation of patients with PA. [37] With MRI, 68% of patients had positive findings of PA, as well as at least 1 arthritic sign. In contrast, with standard radiographs, only 32% of the same patients had positive findings of PA. In a high percentage of psoriatic patients who had no apparent arthritic signs and symptoms, MRIs revealed hand articular involvement, particularly distention of the capsule and periarticular edema.

T1-weighted sequences, supplemented by a short tau inversion recovery (STIR) or T2-weighted fat-suppression (FS) sequence, are generally performed for visualizing inflammation and structural damage in PA. T1-weighted sequences after intravenous injection of gadolinium-containing contrast agent aids identification of inflamed tissue in peripheral joints and can be performed with or without FS. Contrast injection is generally not used in axial disease. [38]

In patients with PA, MRIs of the temporomandibular joint can show slight anterior displacement of the disc, as well as large condylar erosions and joint effusion, either with or without the use of contrast agents.

Thickened nails with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images are typical findings of nail involvement. MRI can show the underlying histopathologic changes of edematous and/or fibrotic synovial tissue, which can cause erosions of cortical bone and can eventually lead to complete destruction of the joint. The terminal tuft may show edema and enhancement with psoriatic involvement of the nail bed.

Morrison et al summarized psoriatic findings in the ankle and foot. [39] The sausage digit is a typical clinical finding in PA and can be seen as diffuse soft tissue edema of the digits. Tenosynovitis, an increase in fluid in the tendon sheath, as well as enhancement related to synovial proliferation, may be seen. Enthesis inflammation manifests itself as plantar fasciitis, with edema and enhancement of the proximal plantar fascia and the adjacent calcaneus. Reactive edema in the adjacent tissue beneath the tendon is linked to involvement of the tendon sheath.

Effusions and synovial proliferation can be seen as a result of joint involvement. Synovial proliferation within joints is seen as "dirty fluid" on T2-weighted images. Inflamed synovial tissue is strongly enhancing on gadolinium-enhanced images. Chronic synovial proliferation can demonstrate a high T1 signal, representing hyperplasia of subsynovial fibrofatty connective tissue without a pannus. The bursae may demonstrate fluid and enhancing synovial tissue; this is true for the anatomic bursae—in particular, the retrocalcaneal bursa and the adventitial bursa—as a result of friction.

McQueen et al described the initial steps in forming an Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) MRI scoring system for peripheral PA. [40, 41] Four readers scored a preexisting MRI dataset (finger joints) from 10 patients with peripheral PA. Bone erosion, bone edema, synovitis, tendinopathy, and extracapsular features of inflammation (including enthesitis) were assessed. The results demonstrated that bone edema and erosion showed moderate to high scoring reliability and that soft tissue inflammation showed a lower scoring reliability.

Healy et al assessed 17 patients with psoriatic dactylitis who underwent a change of treatment, usually to methotrexate. [42] MRI scans of the affected hand or foot were performed before and after treatment, and MRI images demonstrated widespread abnormalities in the digits of patients with PA. Improvement was seen after treatment; however, there was not a close relationship between the extent of abnormalities seen on MRI and any of the clinical indices of dactylitis.

Marzo-Ortega et al found infliximab to be efficacious in reducing bone edema in psoriatic arthritis, as assessed with MRI. [43]

MRI imaging methods such as dynamic contrast-enhanced-MRI and whole-body MRI are promising alternatives for comprehensive study of PA patients in the near future. [17, 36]

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography (US) is useful for assessing extent of disease, identifying inflammatory changes, monitoring treatment, and guiding intra-articular steroid interventions. [17, 29, 36, 44] US is also considered a highly specific technique for visualizing bone abnormalities, especially in the examination of the small joints. In addition, US can aid in the differential diagnosis, such as helping to distinguish RA from PA by differences in the nail ventral plate. [22] The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) has endorsed the use of US in early diagnosis of enthesitis, peripheral arthritis, tenosynovitis, and bursitis.

US examinations are performed using B-mode US, most often in combination with color or power Doppler ultrasound. [17] In PA, joint effusion and synovitis result in hypoechoic sonograms in which the joint space is widened. In some cases, a pseudocystic image connected with the joint space can be observed. Increased thickness of the joint capsule can also be present. The joint capsule is usually clearly distinct from the condylar head, which appears as a linear hyperechoic line with posterior shadowing. The nail can be demonstrated as an apparent bilayer on US, with obliteration of the bilayer with onychopathy of psoriasis. [38] In a cross-sectional study of 141 PA outpatients [45] , the power Doppler global score and the gray-scale entheses score were both found to be higher in patients with active disease than in patients with inactive disease.

The ultrasonographic features of dactylitis in PA have been investigated by Kane et al, and flexor tenosynovitis was detected in more than 90% of the tested patients. An association between dactylitis and articular synovitis was noted in more than 50% of patients. [46]

Fournie et al prospectively compared power Doppler ultrasound findings in 25 fingers of patients who had RA with findings in 25 fingers of patients who had PA and found that in both RA and PA, patients had erosive synovitis and tenosynovitis. [23] Extrasynovial changes such as enthesitis occurred in 21 of 25 patients (84%) with PA, whereas no patients with RA had extrasynovial changes. The main patterns of extrasynovial changes were capsular enthesophytes, juxta-articular periosteal reaction, enthesopathy at the site of deep flexor tendon insertion on the distal phalanx, subcutaneous soft tissue thickening of the finger pad, subcutaneous soft tissue thickening of the entire finger, and pseudotenosynovitis. Of the 21 patients with PA whose fingers showed extrasynovial changes, synovial changes were apparent in 60%.

Nuclear Imaging

Bone scanning is a useful technique for assessing the inflammatory nature and extent of PA. Whole-body scintigraphy shows the distribution of active joint disease, and abnormal radiotracer uptake precedes findings on plain radiographs. Bone scanning is highly sensitive but not specific; bone scans may show that inflammation exists, but a positive finding is not diagnostic of PA and must be correlated with clinical findings.

Enthesopathies may be readily detected on bone scans and show hyperactive foci. This is the case when technetium-99m (99mTc) bisphosphonate bone scans are centered on the chest wall, where the jugular notch, costal notches, and xiphoid are most commonly involved. Enthesopathy manifests itself with a radiologic triad: hyperostosis, osteitis, and periostitis syndrome.

Bone scans are also useful for assessing palmaris et plantaris and a related condition, pustulotic arthrosteitis (PAO). The bone scan can show characteristic, bullhead-like, high tracer uptake in the sternocostoclavicular region. In the bullhead sign, the manubrium sterni represents the upper skull of the bull, and the inflamed sternoclavicular joints correspond to the horns. [47]

Other types of inflammatory arthritis, as well as infection and trauma, can sometimes mimic PA when a bone scan is used. Tc-99m phosphate scans show the location and distribution of active lesions. Scintigraphy enables the inexpensive and simple assessment of joints in the body, but the anatomic detail is poor and the specificity is low.

In one study, thermal infrared imaging was used to record 280 temperature curves of 14 finger joints of 9 healthy controls and 11 patients with psoriatic arthritis. The PA patients presented with prolonged and delayed rewarming processes characterized by the undershoot onset subsequent to completion of isometric exercises, followed by faster temperature increases. Region classification based on model parameters demonstrated that the interphalangeal joint of the thumb can be used to discriminate between healthy areas and affected areas, providing 100% true-positive discrimination for PA-affected regions and 88.89% for healthy regions. [48]

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the abdomen shows fusion of the sacroiliac joints. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Posteroanterior radiograph of the hands shows wrist fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows posterior element fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows syndesmophytes at the C2-3 and C6-7 levels with zygapophyseal joint fusion. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the lumbar spine shows nonmarginal syndesmophytes. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis shows sacroiliac joint beading/erosions. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Dorsal view of the hands shows psoriatic rash and sausage swelling on the right second finger. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the hands shows subchondral erosions of the fourth left distal interphalangeal joint and right third and fourth proximal interphalangeal joints with periosteal reaction. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the feet shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the thumb shows arthritis mutilans. Courtesy of Bruce M. Rothschild, MD.

-

Left, typical appearance of psoriasis with silvery scaling on a sharply marginated and reddened area of the skin overlying the shin. Right, thimblelike pitting of the nail plate in a 56-year-old woman who has had psoriasis for the past 23 years. Nail pitting, transverse depressions, and subungual hyperkeratosis often occur in association with psoriatic disease of the distal interphalangeal joint. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Radiograph of both hands (same patient as in previous image, right-side image) shows extensive erosive changes around the wrists, carpus, and metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. The patient tested negative for rheumatoid factor. Note the lack of juxta-articular osteoporosis. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis in a male patient shows sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the pelvis in a male patient with sacroiliitis in association with psoriasis. The CT scans show subtle changes of sacroiliitis more clearly than do conventional radiographs. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Left, lateral radiograph of the dorsal spine of a 38-year-old man shows spondylitis in association with psoriasis. Note the squaring of the anterior vertebral bodies. Right, radiograph of the pelvis in the same patient shows sacroiliitis and erosive changes around both hip joints. Courtesy of Ali Nawaz Khan, MBBS.

-

Radiograph shows an example of the pencil-in-cup deformity in the metacarpophalangeal joint: a classic psoriatic finding. Courtesy of Michael A. Bruno, MD.

-

Radiograph views of the fourth finger show diffuse soft tissue swelling. This is a nonspecific finding and can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, lupus, Reuter syndrome, gout, and infection. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.

-

Radiograph showing extensive bony destruction around the interphalangeal joint of the second toe. There is associated widening of the joint space, which helps distinguish this condition from osteoarthritis. The base of the middle phalanx is expanded, and there is diffuse soft-tissue swelling but no osteoporosis. Marked osseous erosion about the joint has produced a characteristic pencil-in-cup deformity. Courtesy of Michael R. Aiello, MD.