Practice Essentials

Pulmonary aspergillosis is a spectrum of mycotic diseases caused by the Aspergillus species, usually A fumigatus. [1, 2] This intensely antigenic and ubiquitous soil fungus is commonly found in the sputum of healthy individuals. However, in susceptible hosts, its ability to invade the arteries and veins facilitates its hematogenous spread. The development of disease and its histologic, clinical, and radiologic manifestations depend on the virulence and number of spores inhaled and, more importantly, on the patient's immune status. [3, 4, 5, 6]

Pulmonary aspergillosis may take any of the following 4 forms [1, 2, 4, 5, 6] :

-

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) - Caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to the fungus; most commonly occurs in persons with asthma

-

Saprophytic aspergillosis, or aspergilloma - The most common form; noninvasive and involves colonization of preexisting cavities

-

Chronic necrotizing aspergillosis (also called airway-invasive or semi-invasive aspergillosis) - A chronic, cavitary, pneumonic illness that often affects patients with preexisting chronic lung disease

-

Angioinvasive aspergillosis - Affects immunocompromised patients and is often fatal

If left untreated, invasive aspergillosis can approach 100% mortality. If invasive aspergillosis is suspected, extensive diagnostic workup is necessary, and treatment should be initiated early to reduce morbidity and mortality. [4]

The primary radiologic criteria for ABPA include fixed or transitory pulmonary infiltrates and central bronchiectasis as a late manifestation. [7, 8]

Pulmonary aspergillosis has been found to be present in approximately 25% of intubated patients with critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with increased 30-day mortality rates. [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]

Imaging modalities

Chest radiography is an initial examination of choice in patients with respiratory symptoms or suspected pulmonary disease. [7, 8] However, many different causes of bronchiectasis, including ABPA, cannot be accurately diagnosed on chest radiographs. Also, radiographic features of pulmonary aspergillosis are generally nonspecific.

The European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, the European Confederation of Medical Mycology, and the European Respiratory Society have published recommendations for making the diagnosis based on clinical, radiologic, and microbiologic data. Chest CT and thin-section multidetector CT (MDCT) are recommended to detect pulmonary infiltrates. Pulmonary CT angiography is recommended to identify vessel occlusion or erosion. [14] Specific recommendations include the following:

-

Chest computed tomography and bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) are strongly recommended in patients with suspected of having pulmonary invasive aspergillosis (IA) .

-

For diagnosis, direct microscopy, preferably using optical brighteners, histopathology, and culture are strongly recommended.

-

Serum and BAL galactomannan measures are recommended as markers for the diagnosis of IA.

-

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) should be considered in conjunction with other diagnostic tests.

If invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is suspected, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends performing CT scanning of the chest, regardless of chest radiography findings. While its routine use is not recommended, contrast is recommended when a nodule or a mass is close to a large vessel. [15]

Although features of ABPA on CT scans are not specific, the demonstration of bronchial dilatation, wall thickening, and centrilobular nodules in an asthmatic patient should suggest the diagnosis. [16] The demonstration of a mobile mass within a cavity on supine and prone scans is virtually diagnostic of a mycetoma.

The CT scan appearances of chronic necrotizing aspergillosis are also nonspecific, but CT does provide useful information regarding the extent of pulmonary disease and any associated pleural thickening. In a study of sequential CT images of 30 cases of chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, Ando and colleagues reported the most common findings were enlarged consolidation and/or consolidation and/or ground glass opacity (70%), dilatation of the cavity (26%), and extension to the opposite lung (22%). [17]

CT scan findings in angioinvasive aspergillosis are more specific, and the presence of nodules with a halo of ground-glass attenuation in the appropriate clinical setting allows confident diagnosis.

For in vivo detection of Aspergillus pulmonary infections, radiolabeled Aspergillus-specific monoclonal antibodies and iron siderophores may hold potential for clinical diagnosis. [6, 18]

An assay to detect galactomannan, a major component of the Aspergillus cell wall, is available. Patients who are at high risk may be screened for the development of invasive Aspergillus infection by monitoring serum galactomannan levels weekly. Several new diagnostic tests for invasive aspergillosis are available to complement conventional galactomannan testing. [19, 20, 21]

Limitations of techniques

The appearances of the different types of thoracic aspergillosis are nonspecific, and a wide variety of lesions can mimic an aspergilloma. Examples of these include chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, angioinvasive aspergillosis, a tuberculous cavity with a Rasmussen aneurysm, cavitating bronchogenic carcinoma, lung abscess, hematoma, and Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia. Similarly, bronchial dilatation has a variety of causes.

Radiograph

In allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), chest radiographic appearances include the following: (1) fleeting alveolar subsegmental or lobar infiltrates, which are usually bilateral (65%) and predominant in the upper lobes (50%); (2) central 1- to 2-cm ring shadows that represent varicose or cystic bronchiectasis; and (3) tram-link bronchial walls caused by edema. [1, 7, 8] The second-order bronchi may become plugged with mucus, and they may be visible as 2.5- to 6-cm long V- or Y-shaped branching tubular opacities that may grow over time and persist for months; this is the so-called finger-in-glove sign (see the image below).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. This image shows branching finger-in-glove tubular opacities in the left lower lobe (ie, retrocardiac location) due to mucus plugging of ectatic bronchi.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. This image shows branching finger-in-glove tubular opacities in the left lower lobe (ie, retrocardiac location) due to mucus plugging of ectatic bronchi.

Other features include lobar consolidation, atelectasis, postobstructive pneumonia, cavitation, air trapping, and parenchymal scarring or fibrosis, all of which are more pronounced in the upper lobes. Focal pleural thickening is also reported. Occasionally, mycetomas develop in ectatic bronchi.

The characteristic chest radiographic appearance of an aspergilloma is that of a round or oval mass with the opacity of that of a soft-tissue mass. Often, an adjacent crescent-shaped air space (ie, the air-crescent sign) separates the fungal ball from the cavity wall (see the image below).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows multiple aspergillomas in a patient with tuberculosis. Note the numerous air crescents.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows multiple aspergillomas in a patient with tuberculosis. Note the numerous air crescents.

The mycetoma may rarely contain amorphous or rimlike calcification. The fungal ball is usually mobile and moves when the patient changes position. Often, extensive, adjacent, apical pleural thickening may be present; this finding may herald the development of the mycetoma (see the image below).

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows a left upper lobe mycetoma with an indwelling catheter for drug delivery.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows a left upper lobe mycetoma with an indwelling catheter for drug delivery.

The radiologic manifestations of chronic necrotizing aspergillosis include unilateral or bilateral segmental areas of consolidation that are predominant in the upper lobes; frequently, these progress to cavitation (see the image below). Pleural thickening is also a recognized feature.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows chronic, cavitating, upper lobe consolidation in a patient with long-standing fibrosing alveolitis; this finding is consistent with chronic necrotizing aspergillosis. Aspergillus fumigatus was cultured from the sputum and percutaneous aspiration samples.

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows chronic, cavitating, upper lobe consolidation in a patient with long-standing fibrosing alveolitis; this finding is consistent with chronic necrotizing aspergillosis. Aspergillus fumigatus was cultured from the sputum and percutaneous aspiration samples.

The most common chest radiographic appearance of invasive aspergillosis is that of patchy areas of consolidation, which progress despite the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Multiple nodules and peripheral, wedged-shaped lesions caused by hemorrhagic infarcts are also observed as the disease progresses. These frequently become cavitated, and an air-crescent sign that mimics mycetoma may also be observed.

Degree of confidence

The many different causes of bronchiectasis, including ABPA, cannot be accurately diagnosed with radiographs. Also, the radiographic features of pulmonary aspergillosis are generally nonspecific.

Cortese et al were able to show the limited usefulness of conventional chest radiographs in the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with cystic fibrosis. [7] The authors found the most significant abnormalities were nonspecific, and they were commonly seen in cystic fibrosis without ABPA that persisted after treatment in most cases.

An air-crescent sign may occur in the following: aspergilloma, chronic necrotizing aspergillosis, angioinvasive aspergillosis, tuberculous cavity with a Rasmussen aneurysm, cavitating bronchogenic carcinoma, lung abscess, hematoma, and P (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia.

CT Scanning

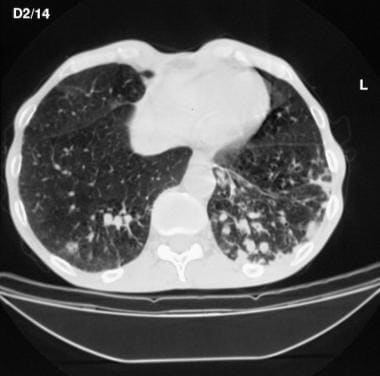

Bronchiectasis and peribronchial thickening are the most common CT scan findings in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) (see the image below). Appearances tend to be more severe than in those of chronic, uncomplicated asthma. [22, 23] ABPA typically involves the segmental and subsegmental bronchi, particularly those in the upper lobes. However, studies have shown that central bronchiectasis simply indicates long-standing severe inflammation; as a marker, it is not as specific for ABPA, as was once thought. CT features of invasive PA vary according to the degree of neutropenia and underlying disease. [24, 25]

High-resolution computed tomography scan. This image shows peribronchial thickening and apparent nodular opacities in the lower lobes due to bronchiectasis with mucoid impaction.

High-resolution computed tomography scan. This image shows peribronchial thickening and apparent nodular opacities in the lower lobes due to bronchiectasis with mucoid impaction.

High-attenuating mucoid impaction, which is present in as many as 30% of patients, is a characteristic finding. One study suggests that a CT density value of 70 Hounsfield units is an adequate cutoff value for high-attenuation mucoid impaction. [26] High-attenuation mucoid impaction is associated with initial serologic severity and frequent relapses, but it does not influence complete remission. [26, 27] Occasionally, lobar or segmental atelectasis may be a feature. Mucus plugging of the small airways can be observed on high-resolution CT scans, with resultant centrilobular nodularity and the tree-in-bud sign. [16] Abnormalities of lung attenuation due to either mosaic perfusion or air trapping may also be identified. Scans obtained during expiration are useful in differentiating the findings in this instance.

The CT scan and chest radiographic appearances of an aspergilloma are similar (see the first 2 images below). The fungal ball is seen as a mass of soft-tissue attenuation within a pulmonary cavity. An anterior air crescent is visible if the patient is supine (see the third image below). The mobile nature of the mass can be demonstrated by scanning the patient in the prone position; the fungal ball falls to the dependent portion of the cavity. The cavity wall and adjacent pleura are frequently thickened, although these findings have been shown to resolve with successful treatment or with the spontaneous resolution of the infection.

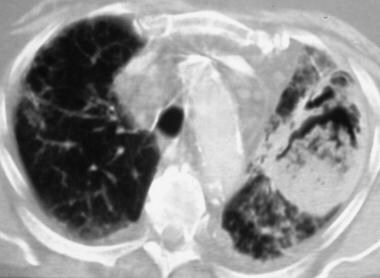

High-resolution computed tomography scan shows central bronchiectasis in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The patient had previously undergone left upper lobectomy for severe bronchiectasis.

High-resolution computed tomography scan shows central bronchiectasis in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The patient had previously undergone left upper lobectomy for severe bronchiectasis.

Axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan obtained through the lower thorax. This image shows a subtle left lower lobe nodule due to invasive aspergillosis in a renal transplant recipient. The patient had multiple other nodules, one of which was examined at biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Note the esophagus has thickened walls secondary to concurrent cytomegaloviral infection.

Axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan obtained through the lower thorax. This image shows a subtle left lower lobe nodule due to invasive aspergillosis in a renal transplant recipient. The patient had multiple other nodules, one of which was examined at biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Note the esophagus has thickened walls secondary to concurrent cytomegaloviral infection.

Axial computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic arch. This image shows a masslike consolidation, with a developing air crescent adjacent to the central sequestrated lung, which mimics a mycetoma.

Axial computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic arch. This image shows a masslike consolidation, with a developing air crescent adjacent to the central sequestrated lung, which mimics a mycetoma.

CT scan findings in chronic necrotizing aspergillosis include areas of chronic, progressive, peripheral consolidation; multiple nodular opacities; and low-attenuating, masslike lesions. Abnormalities may be unilateral or bilateral, with an upper-lobe predilection. Cavitation is a common feature, and this often leads to the development of an intracavitary segment of sequestrated lung, which may mimic a mycetoma. Extension into the chest wall and mediastinum has also described.

CT scan findings of angioinvasive aspergillosis include multiple nodules associated with a halo of ground-glass attenuation, which represents adjacent hemorrhage, and pleural-based, wedge-shaped areas of consolidation, which correspond to hemorrhagic infarcts. The air-crescent sign may be observed in the recovery phase.

Degree of confidence

Although the CT scan features of ABPA are not specific, the demonstration of bronchial dilatation, wall thickening, and centrilobular nodules in an asthmatic patient should suggest the diagnosis. The presence of ABPA is even more likely if bronchiectasis is severe, affects 3 or more lobes, and has a central distribution. Many pulmonary lesions become cavitated; however, the demonstration of a mobile mass within a cavity on supine and prone scans is virtually diagnostic of a mycetoma.

CT scan appearances of chronic necrotizing aspergillosis are nonspecific, although CT scanning does provide accurate information regarding the distribution and extent of pulmonary disease and any associated pleural thickening.

CT scan findings in angioinvasive aspergillosis are more specific, and the presence of nodules with a halo of ground-glass attenuation in the appropriate clinical setting allows confident diagnosis.

The causes of false-positive and false-negative results are the same as those with chest radiography. In one report [28] , high-resolution chest CT was negative in 22 of 60 patients with glucocorticoid-naive ABPA.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. This image shows branching finger-in-glove tubular opacities in the left lower lobe (ie, retrocardiac location) due to mucus plugging of ectatic bronchi.

-

High-resolution computed tomography scan. This image shows peribronchial thickening and apparent nodular opacities in the lower lobes due to bronchiectasis with mucoid impaction.

-

High-resolution computed tomography scan shows central bronchiectasis in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The patient had previously undergone left upper lobectomy for severe bronchiectasis.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows multiple aspergillomas in a patient with tuberculosis. Note the numerous air crescents.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows chronic, cavitating, upper lobe consolidation in a patient with long-standing fibrosing alveolitis; this finding is consistent with chronic necrotizing aspergillosis. Aspergillus fumigatus was cultured from the sputum and percutaneous aspiration samples.

-

Axial computed tomography scan obtained at the level of the aortic arch. This image shows a masslike consolidation, with a developing air crescent adjacent to the central sequestrated lung, which mimics a mycetoma.

-

Axial nonenhanced computed tomography scan obtained through the lower thorax. This image shows a subtle left lower lobe nodule due to invasive aspergillosis in a renal transplant recipient. The patient had multiple other nodules, one of which was examined at biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. Note the esophagus has thickened walls secondary to concurrent cytomegaloviral infection.

-

Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows a left upper lobe mycetoma with an indwelling catheter for drug delivery.

-

Flush thoracic aortogram obtained in a patient with a mycetoma and hemoptysis. This image shows anastomosis involving the bronchial artery, intercostal arteries, and pulmonary artery. Note also the anastomosis with blood vessels from the lateral thoracic wall.

-

Right bronchial angiogram in a 40-year old man with a known right lung mycetoma (arrow). This image shows extensive anastomosis between the right bronchial artery and the intercostal arteries.

-

This posteroanterior chest radiograph was obtained in a 36-year-old woman who was previously treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. The patient had a left upper lobe mycetoma and presented with recurrent life-threatening hemoptysis. The disease failed to respond to systemic and local antifungal therapy.

-

Angiogram of the left thyrocervical trunk in a 36-year-old woman with a left upper lobe mycetoma and a past history of being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. This image shows that the blood supply to the mycetoma is derived from the thyrocervical trunk.

-

Delayed-phase angiogram in a 36-year-old woman with a left upper lobe mycetoma and a past history of being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis. This image shows anastomosis of the branches of the thyrocervical trunk with the left pulmonary artery at the site of the mycetoma.

-

Angiographic series of the thyrocervical trunk in a 36-year-old woman with a left upper lobe mycetoma and a past history of being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis (same patient as in the previous 3 images). This image was obtained after embolization and shows a pruned-tree appearance of the arterial trunks. Note that the left internal mammary artery had to be sacrificed.

-

Angiogram of the right fifth intercostal artery in a 36-year-old woman with a left upper lobe mycetoma and a past history of being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis (same patient as in the previous 4 images). This image shows that the artery meanders around to the left hemithorax and supplies the left-sided mycetoma.

-

Angiogram of the right 5th intercostal artery in a 36-year-old woman with a left upper lobe mycetoma and a past history of being treated for pulmonary tuberculosis (same patient as in the previous 5 images). This image shows the blind stump of the artery after embolization. When this article was written, the patient was alive and well and had had no further episodes of hemoptysis for more than 3 years.