Practice Essentials

Genitourinary trauma—injuries involving the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra—occurs in 10-20% of all abdominal trauma cases in adults and children. The kidney is the genitourinary organ most commonly involved, accounting for 65-90% of genitourinary injuries. [1]

The majority of kidney injuries result from blunt trauma. [2] Causes of blunt kidney trauma include motor vehicle accidents (MVAs), falls, and various types of sports accidents. MVAs are the most common cause, responsible for 63% of blunt kidney injuries. Although the kidneys are relatively protected retroperitoneal structures cushioned by copious fat, deceleration and acceleration forces appear to play major roles in blunt injuries, and particularly injury at the renal hilum, involving the ureter, renal artery, and renal vein. [3]

Although penetrating kidney trauma is less common than blunt kidney trauma it is often more severe, due to the nature of the injury itself. Penetrating kidney trauma can be high-velocity or low-velocity, such as gunshot wounds, stab wounds, and other impalements. The direct organ contact can cause parenchymal, vascular, and ureteral lacerations. Complications include large-volume retroperitoneal hemorrhage, which can result in hemodynamic instability. Penetrating kidney trauma often occurs in the context of multi-organ trauma, which complicates management. [4, 5, 6]

Accurate imaging and staging of kidney trauma is critical for guiding the management of these cases, starting with the choice between surgical and nonsurgical treatment. Follow-up imaging can be used as part of nonoperative management, which is increasingly preferred. When intervention is indicated, imaging study findings can guide the selection of technique.

Grading of kidney injury

The most widely utilized system for grading the severity of kidney injury is the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) scale, which was developed in 1989 and updated in 2018 to include renal vascular injury. Of the five grades in the AAST scale, the highest three (grades III, IV, and V) can be associated with renal vascular injury (ie, vascular laceration, pseudoaneurysm, or arteriovenous [AV] fistula).

On contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), a laceration appears as an extravascular collection of contrast that increases in size during a delayed phase. Pseudoaneurysm and AV fistula appear as focally dilated contrast collections that decrease in Hounsfield units during a delayed phase. [7]

It should also be noted that a subcapsular hematoma can be large enough to compress and distort the renal parenchyma. This compression can compromise blood flow to the parenchyma, resulting in hypertension due to activation of the renin-angiotensin system, a phenomenon known as Page kidney. [8]

An individual kidney may have injuries of multiple grades. In this circumstance, grading should be assigned to the highest classification. There are separate published AAST scales for ureteral, bladder, and urethral injuries.

These scales have been widely accepted by trauma surgeons as the mainstay of urogenital trauma scaling. Using a standardized classification system promotes better communication between radiologists and the trauma team, which ultimately can improve patient management and outcome.

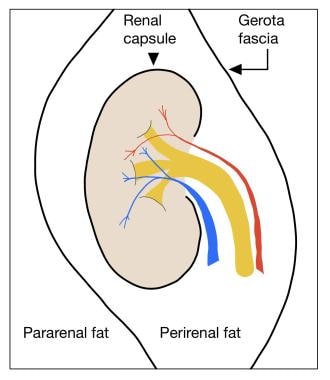

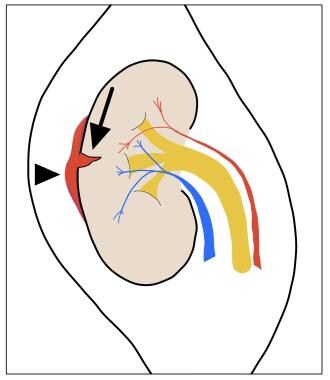

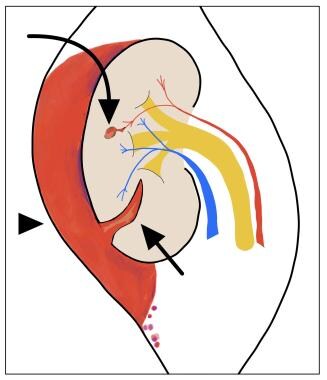

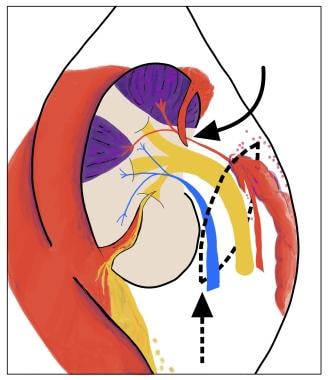

In the AAST scale, the renal capsule and Gerota fascia are landmarks used for classifying kidney injury. See the image below.

Illustration shows the spaces around the kidney and fascial landmarks that are important in differentiating the grades of injury and pattern of hemorrhage spread. Grade I hematomas do not extend beyond the renal capsule. Grade II hematomas can extend beyond the renal capsule but not beyond the Gerota fascia. Both grades I and II remain confined to the perirenal space. Grade III, IV, and V injuries can involve disruption of the Gerota fascia and extension into the pararenal space.

Illustration shows the spaces around the kidney and fascial landmarks that are important in differentiating the grades of injury and pattern of hemorrhage spread. Grade I hematomas do not extend beyond the renal capsule. Grade II hematomas can extend beyond the renal capsule but not beyond the Gerota fascia. Both grades I and II remain confined to the perirenal space. Grade III, IV, and V injuries can involve disruption of the Gerota fascia and extension into the pararenal space.

AAST grade I kidney injury

AAST grade I kidney injury is defined by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Subcapsular hematoma not extending beyond the renal capsule

-

Parenchymal contusion without laceration

See the images below.

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade I kidney injury are subcapsular hematoma (arrowhead) not extending beyond the renal capsule and/or parenchymal contusion (arrow) without laceration.

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade I kidney injury are subcapsular hematoma (arrowhead) not extending beyond the renal capsule and/or parenchymal contusion (arrow) without laceration.

Grade I injury: contusion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows an ill-defined area of decreased enhancement in the right kidney representing a renal contusion. This must be differentiated from a more serious grade IV peripheral segmental infarction, which shows as lack of enhancement rather than decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade I injury: contusion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows an ill-defined area of decreased enhancement in the right kidney representing a renal contusion. This must be differentiated from a more serious grade IV peripheral segmental infarction, which shows as lack of enhancement rather than decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Note the well-defined outer margin, which denotes that the hematoma is contained within the Gerota fascia. This must be differentiated from grade III and higher injuries, which can extend beyond the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Note the well-defined outer margin, which denotes that the hematoma is contained within the Gerota fascia. This must be differentiated from grade III and higher injuries, which can extend beyond the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma, Page kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Mild deformity of the renal parenchyma caused by the hematoma is evident. Note that if a subcapsular hematoma becomes large enough, it can take a lentiform shape rather than a crescent shape. This is important, since larger subcapsular hematomas compressing the renal parenchyma may cause a hypertensive phenomenon known as Page kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma, Page kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Mild deformity of the renal parenchyma caused by the hematoma is evident. Note that if a subcapsular hematoma becomes large enough, it can take a lentiform shape rather than a crescent shape. This is important, since larger subcapsular hematomas compressing the renal parenchyma may cause a hypertensive phenomenon known as Page kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

AAST grade II kidney injury

AAST grade II kidney injury is defined by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Renal parenchymal laceration ≤1 cm in depth without urinary extravasation

-

Perirenal hematoma confined to Gerota fascia

See the images below.

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade II kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration ≤1 cm in depth (arrow) without urinary extravasation and/or perirenal hematoma confined by Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade II kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration ≤1 cm in depth (arrow) without urinary extravasation and/or perirenal hematoma confined by Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

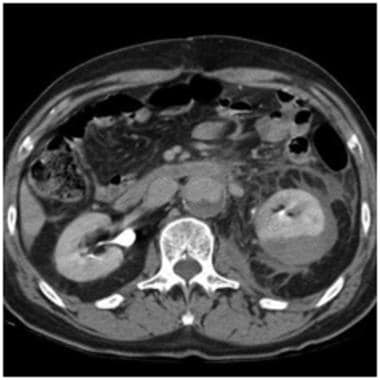

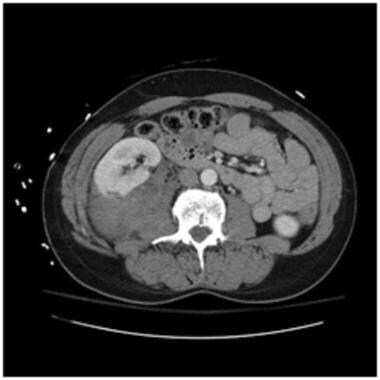

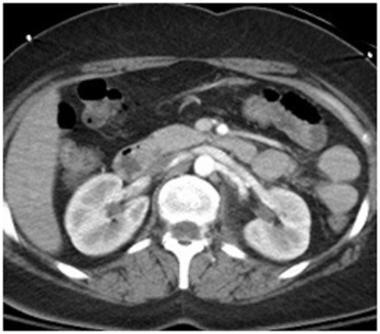

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. There is a subtle 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole posterolateral cortex, best seen on the next image obtained in the coronal plane. If the laceration depth measured greater than 1 cm, the injury would be classified as grade III.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. There is a subtle 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole posterolateral cortex, best seen on the next image obtained in the coronal plane. If the laceration depth measured greater than 1 cm, the injury would be classified as grade III.

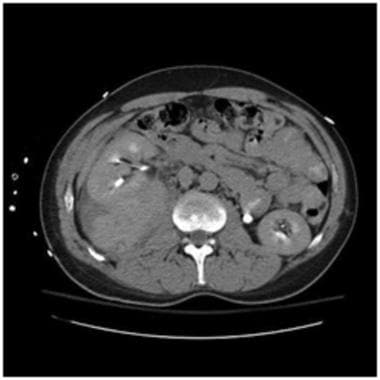

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. The 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole is better seen on this coronal plane.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. The 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole is better seen on this coronal plane.

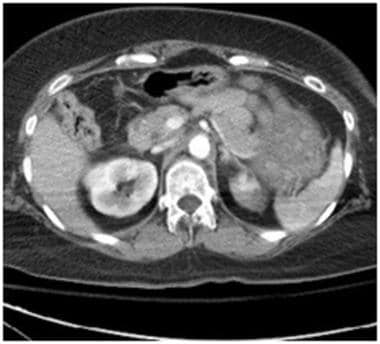

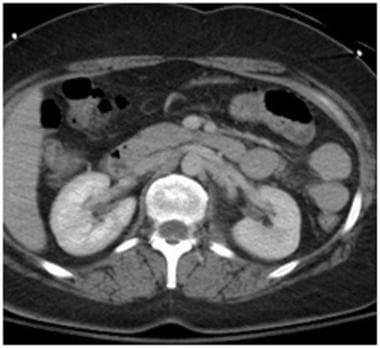

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a questionable area of decreased renal attenuation in the left upper pole as seen on this axial plane, which was initially thought to represent a streak artifact caused by the patient's arms at the sides. The next image shows the laceration in the sagittal plane which corresponds to the same location. There is a very small adjacent perirenal hematoma. This case illustrates the importance of carefully inspecting the images when degraded by such artifacts.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a questionable area of decreased renal attenuation in the left upper pole as seen on this axial plane, which was initially thought to represent a streak artifact caused by the patient's arms at the sides. The next image shows the laceration in the sagittal plane which corresponds to the same location. There is a very small adjacent perirenal hematoma. This case illustrates the importance of carefully inspecting the images when degraded by such artifacts.

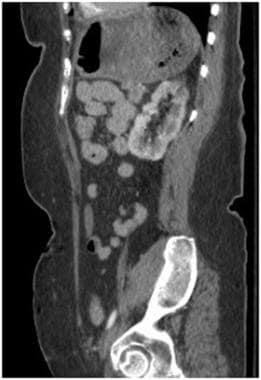

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above better demonstrates the area of decreased renal attenuation on this sagittal plane. The laceration can clearly be seen in the upper pole corresponding to the same location as the axial plane.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above better demonstrates the area of decreased renal attenuation on this sagittal plane. The laceration can clearly be seen in the upper pole corresponding to the same location as the axial plane.

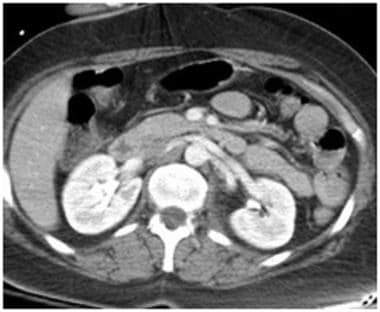

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. There is also a laceration measuring less than 1 cm deep. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. There is also a laceration measuring less than 1 cm deep. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan to exclude contrast extravasation outside the collecting system. If urinary contrast extravasation was found, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Also notice that despite the large size of the hematoma, there is no deformity of the kidney as seen with large subcapsular hematomas. This feature helps to distinguish the location of the hematoma as either subcapsular or perirenal. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan to exclude contrast extravasation outside the collecting system. If urinary contrast extravasation was found, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Also notice that despite the large size of the hematoma, there is no deformity of the kidney as seen with large subcapsular hematomas. This feature helps to distinguish the location of the hematoma as either subcapsular or perirenal. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

AAST grade III kidney injury

AAST grade III kidney injury is defined by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Renal parenchymal laceration > 1 cm in depth without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation

-

Any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury (pseudoaneurysm) or active bleeding contained within Gerota fascia

See the images below.

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade III kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration > 1 cm in depth (arrow), without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation; and/or any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury (pseudoaneurysm; curved arrow) or active bleeding contained within Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade III kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration > 1 cm in depth (arrow), without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation; and/or any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury (pseudoaneurysm; curved arrow) or active bleeding contained within Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

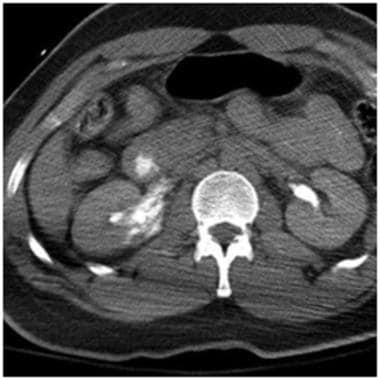

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a laceration greater than 1 cm in depth (measured from cortex into parenchyma) with an associated perirenal hematoma. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia in the perirenal space. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a laceration greater than 1 cm in depth (measured from cortex into parenchyma) with an associated perirenal hematoma. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia in the perirenal space. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

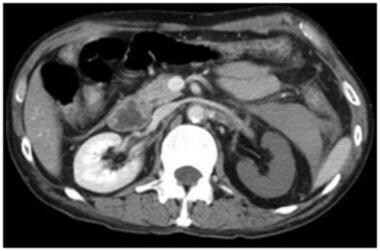

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows no urinary extravasation from the collecting system. If the laceration extended deeper into the collecting system with urinary extravasation, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows no urinary extravasation from the collecting system. If the laceration extended deeper into the collecting system with urinary extravasation, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

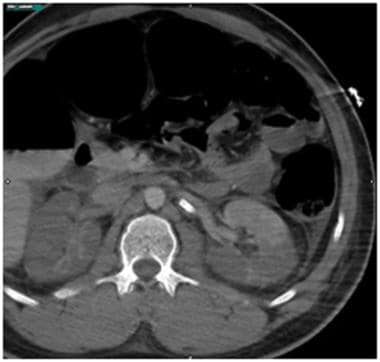

Grade III injury: perirenal hematoma with active bleeding. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a perirenal hematoma. There is a small collection of contrast within the hematoma consistent with active bleeding. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade III injury: perirenal hematoma with active bleeding. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a perirenal hematoma. There is a small collection of contrast within the hematoma consistent with active bleeding. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

AAST grade IV kidney injury

AAST grade IV kidney injury is defined by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Parenchymal laceration extending into the collecting system with urinary extravasation

-

Renal pelvis laceration and/or complete uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ) disruption

-

Segmental renal vein or artery injury with or without infarction

-

Active bleeding beyond Gerota fascia into the retroperitoneal space or peritoneal cavity

-

Segmental or complete kidney infarction due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding

See the images below.

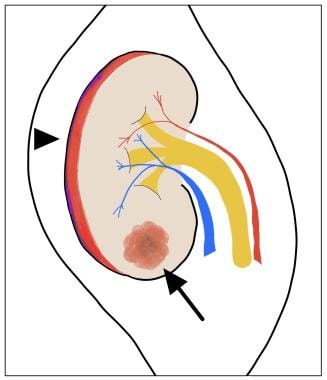

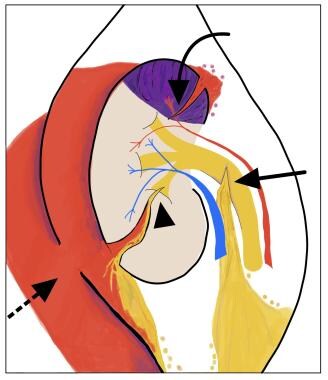

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) defines grade IV kidney injury by the presence of at least one of the following: -Parenchymal laceration extending into the collecting system with urinary extravasation (arrowhead) -Renal pelvis laceration and/or complete ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) disruption (arrow) -Segmental renal vein or artery (arrowhead) injury with (purple) or without infarction -Active bleeding beyond Gerota fascia into the retroperitoneal space or peritoneal cavity (dashed arrow) -Segmental or complete kidney infarction due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) defines grade IV kidney injury by the presence of at least one of the following: -Parenchymal laceration extending into the collecting system with urinary extravasation (arrowhead) -Renal pelvis laceration and/or complete ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) disruption (arrow) -Segmental renal vein or artery (arrowhead) injury with (purple) or without infarction -Active bleeding beyond Gerota fascia into the retroperitoneal space or peritoneal cavity (dashed arrow) -Segmental or complete kidney infarction due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding

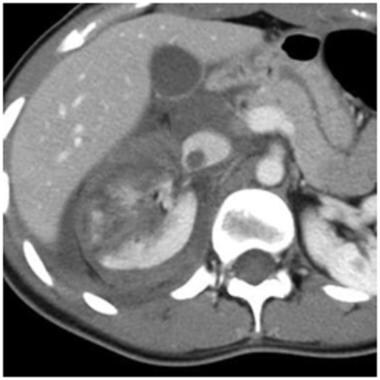

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a well-defined triangular area of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important to avoid a potential pitfall by calling this a contusion which would downgrade the injury to a grade 1 injury and alter appropriate management. Infarctions are typically well-defined with lack of enhancement while contusions are typically ill-defined with decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a well-defined triangular area of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important to avoid a potential pitfall by calling this a contusion which would downgrade the injury to a grade 1 injury and alter appropriate management. Infarctions are typically well-defined with lack of enhancement while contusions are typically ill-defined with decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows another example of segmental infarction. There are two small but well-defined triangular areas of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important not to mistakenly classify this as grade 1 renal laceration since both infarctions and lacerations are typically peripheral. Lacerations tend to be more linear than triangular. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows another example of segmental infarction. There are two small but well-defined triangular areas of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important not to mistakenly classify this as grade 1 renal laceration since both infarctions and lacerations are typically peripheral. Lacerations tend to be more linear than triangular. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

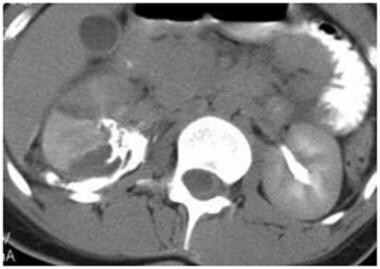

Grade IV injury: urinary extravasation. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA show extensive urinary contrast extravasation from a deep laceration. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan in evaluating for injury at the renal pelvis and uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ). Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade IV injury: urinary extravasation. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA show extensive urinary contrast extravasation from a deep laceration. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan in evaluating for injury at the renal pelvis and uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ). Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

AAST grade V kidney injury

AAST grade V kidney injury is defined by the presence of at least one of the following:

-

Main renal artery or vein laceration or avulsion of the hilum

-

Devascularized kidney with active bleeding

-

Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal anatomy

See the images below.

AAST Grade V (at least one finding below): -Main renal artery or vein laceration (curved arrow) or avulsion of the hilum (dashed arrow and line). -Devascularized kidney with active bleeding. -Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal anatomy.

AAST Grade V (at least one finding below): -Main renal artery or vein laceration (curved arrow) or avulsion of the hilum (dashed arrow and line). -Devascularized kidney with active bleeding. -Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal anatomy.

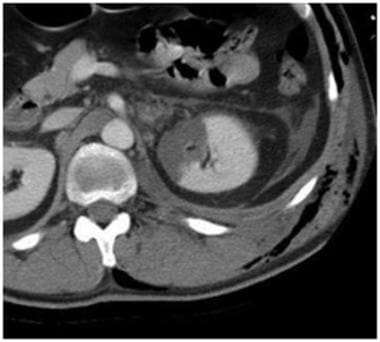

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows normal enhancement of the right kidney with fluid around the UPJ mimicking a perirenal hematoma. Delayed scan on the next image reveals significant UPJ injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows normal enhancement of the right kidney with fluid around the UPJ mimicking a perirenal hematoma. Delayed scan on the next image reveals significant UPJ injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above reveals significant urinary contrast extravasation from UPJ ureteral avulsion. Complete avulsion at the hilum would have resulted in a devascularized kidney in addition to the urinary extravasation at the UPJ. When fluid is located medially near the renal hilum, ureteral injury should be suspected. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above reveals significant urinary contrast extravasation from UPJ ureteral avulsion. Complete avulsion at the hilum would have resulted in a devascularized kidney in addition to the urinary extravasation at the UPJ. When fluid is located medially near the renal hilum, ureteral injury should be suspected. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

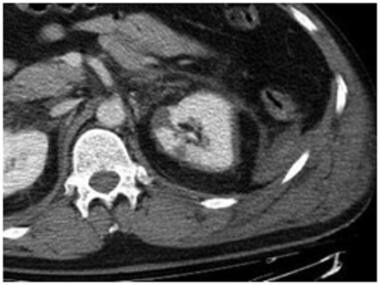

Grade V renal injury: devascularized kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after assault shows dissection of the left renal artery near the origin with lack of enhancement in the kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: devascularized kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after assault shows dissection of the left renal artery near the origin with lack of enhancement in the kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

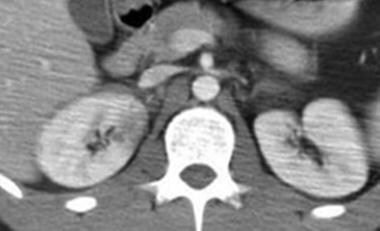

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after motor-pedestrian accident shows complete lack of enhancement in the right kidney and only single segment enhancement in the right kidney from bilateral vascular injury near the renal hila.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after motor-pedestrian accident shows complete lack of enhancement in the right kidney and only single segment enhancement in the right kidney from bilateral vascular injury near the renal hila.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows subsequent placement of a vascular stent which resulted in improved left renal enhancement.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows subsequent placement of a vascular stent which resulted in improved left renal enhancement.

Grade V renal injury: shattered kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows multiple deep lacerations and loss of normal parenchymal anatomy consistent with a shattered kidney. There is thrombus in the inferior vena cava extending from a thrombus in the renal vein. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: shattered kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows multiple deep lacerations and loss of normal parenchymal anatomy consistent with a shattered kidney. There is thrombus in the inferior vena cava extending from a thrombus in the renal vein. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows no laceration but only minimal stranding around the left renal hilum and a thin halo surrounding the left main renal artery on this early phase.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows no laceration but only minimal stranding around the left renal hilum and a thin halo surrounding the left main renal artery on this early phase.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 3-minute delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows asymmetrically decreased enhancement of the left kidney with a persistent nephrogram phase compared to the normal right. Renal hilar injury was suspected prompting a further delayed scan as shown in the next image.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 3-minute delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows asymmetrically decreased enhancement of the left kidney with a persistent nephrogram phase compared to the normal right. Renal hilar injury was suspected prompting a further delayed scan as shown in the next image.

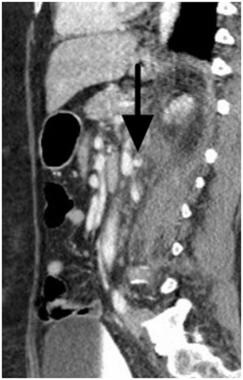

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 45-minute delayed scan in the same patient as above reveals IV contrast in the ureter without urinary extravasation, but the halo around the renal artery remains. A reconstructed sagittal scan shown in the next image reveals injury to the left renal artery.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 45-minute delayed scan in the same patient as above reveals IV contrast in the ureter without urinary extravasation, but the halo around the renal artery remains. A reconstructed sagittal scan shown in the next image reveals injury to the left renal artery.

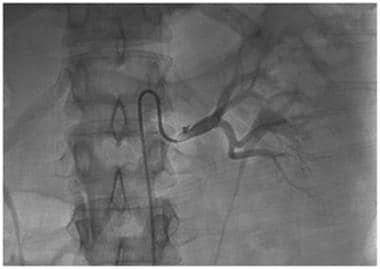

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. On this sagittal plane scan, a subtle defect (arrow) is seen in the renal artery consistent with arterial injury. Follow-up angiogram on the next image reveals the extent of the injury.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. On this sagittal plane scan, a subtle defect (arrow) is seen in the renal artery consistent with arterial injury. Follow-up angiogram on the next image reveals the extent of the injury.

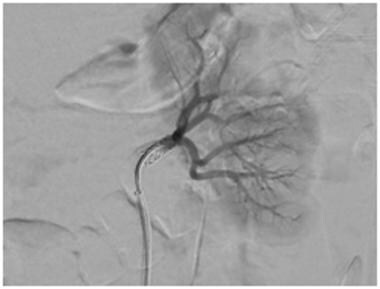

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Follow-up angiogram reveals a small dissection flap in the left renal artery and a small contained perforation.

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Follow-up angiogram reveals a small dissection flap in the left renal artery and a small contained perforation.

Computed Tomography

CT is the gold standard imaging technique for hemodynamically stable blunt trauma patients, according to American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria. [9, 10] Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis can provide a detailed assessment of kidney injuries, including renal contusions, lacerations, hematomas, and active bleeding.

Delayed images obtained in the portal phase can assess for injuries to the collecting system, ureters, and bladder. Delayed images are also useful in evaluating for the presence or absence of renal vein thrombosis.

The ACR's guidelines are concordant with the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for the management of genitourinary trauma, which recommend performing CECT of the abdomen and pelvis (immediate and delayed scans) in all stable blunt trauma patients with hematuria (gross or microscopic) and a systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg. Additional indications for CECT include penetrating abdominal injury and/or significant flank ecchymosis, rapid deceleration, and rib fracture. AUA guidelines recommend immediate intervention when radiologic findings identify a large perirenal hematoma (> 4 cm) and/or vascular contrast extravasation in AAST grade III-IV injuries in hemodynamically unstable patients. [2, 11, 12, 14]

Limitations of CT

The main drawback to CT is the time to complete a CT examination. Fortunately, this is becoming less of a factor with the increasing availability of multidetector-row CT (MDCT) scanners, which are faster and more powerful than single-slice helical CT scanners. MDCT scanners have the ability to acquire thin-section, high-quality images in less time. The faster scan time results in decreased breathing motion artifact, which ultimately produces better-quality images.

Another limitation to CT scanning in the trauma patient is the need to oftentimes scan the patient with the arms at the sides of the body, rather than above the shoulders or head. For imaging of trauma patients, it is recommended to place the arms above the shoulders to improve image quality if there are no indications of shoulder or neck injury. Otherwise, this can result in streak artifact, sometimes significant enough to miss small lacerations, pseudoaneurysms or thrombosis causing a false-negative scan. This has been described in various literature, however, there are no uniform guidelines regarding arm raising during trauma scanning. [14]

Ultrasonography

Rapid availability and the absence of radiation exposure are attractive features of ultrasound (US) imaging, especially in the emergency department (ED). US can be useful for critical decision-making in the setting of trauma. Prior to the acceptance of US as an important tool in the assessment of trauma patients, trauma surgeons relied on more invasive procedures such as exploratory laparotomy to diagnose intra-abdominal injuries. [15]

Several US trauma protocols have been developed over the last few decades to help the trauma team make treatment-altering decisions, including FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma), E-FAST (Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma), and RUSH (Rapid Ultrasound for Shock and Hypotension). Those protocols all use US to quickly assess for key findings in the chest and peritoneal cavity, particularly the presence or absence of free fluid. [16, 17]

In the ED, rapid noninvasive diagnosis with US can decrease mortality, especially in unstable patients. A retrospective study by Lee et al found FAST to be 85% sensitive and 60% specific in predicting the need for laparotomy in hypotensive blunt abdominal trauma patients. [18]

Limitations of ultrasound

Although US has high sensitivity for detection of free fluid in blunt trauma patients, its specificity remains elusive. US is unable to distinguish acute hemorrhage from urinary extravasation, since both blood and urine can appear as hyperechoic free fluid. Depending on the age of the bleeding, hemorrhage may even appear hypoechoic or isoechoic. Other fluid collections such as ascites, chronic hematomas, urinomas, and physiologic menses-related free fluid may mimic hemoperitoneum.

US remains inferior to CT, especially in the absence of free fluid. Compared with CT, US does not have the spatial resolution to locate small renal cortical lacerations, renal pedicle injury, and segmental infarcts. [3, 19, 20, 21] The ability to identify those features is essential for grading kidney injury and ultimately in deciding whether treatment should be conservative or surgical.

The sensitivity of US in detecting renal injuries can vary with patient presentation. Visualization of the inferior and lower pole margins of the kidneys is often limited due to body habitus and/or overlying bowel gas. The limited sensitivity of US for evaluation of the renal pelvis and UPJ is particularly problematic, given the likelihood that these hilar injuries may require surgical intervention.

The sensitivity of renal US also decreases dramatically with decreased operator experience. A retrospective study by Sato et al found that US sensitivity for renal injuries was 44.1% in less-experienced operators compared with 77.6% in expert operators. [22, 23]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has been reported as being comparable to CT in detecting kidney injury and can accurately stage kidney injury. However, MRI is not widely available in all emergency centers, especially after hours. When MRI is available, it should be reserved for stable patients with indeterminate findings on CT or patients who have contraindications to intravenous contrast injection. [24]

Limitations of MRI

The primary limitation of MRI in acute kidney injury imaging is logistics. As stated, MRI is not widely available in all emergency centers after hours. In the unstable patient, MRI is not a feasible option given the long acquisition time of MRI sequences. In addition, injured patients may be unable to hold their breath for extended periods of time, which results in degraded images due to respiratory motion.

Treatment

The treatment of most grade I, II, or III renal injuries is usually conservative, except when a vigorous active hemorrhage is present. In such cases, if the patient is otherwise stable the active hemorrhage may be treated successfully with selective catheter embolization. Occasionally, continued bleeding or extravasation can lead to complications and higher morbidity if not identified and managed appropriately. Follow-up CT is useful for restaging the renal trauma and helps identify patients with progressive worsening on conservative management. Appropriate intervention in these patients can help prevent complications. [25, 26, 27]

Under many circumstances, even large urinary extravasations can heal with conservative treatment; however, stenting is sometimes necessary to facilitate the process. Surgical debridement or repair is usually necessary only when the laceration is accompanied by significant devitalized renal tissue, particularly when concomitant intraperitoneal injuries are also present. The main purpose of such a procedure is to prevent the development of urinoma, infection, or abscess. In the absence of such repair, a nephrectomy may be needed later to prevent sepsis. [28, 29]

Treatment for complete UPJ tears is surgical repair, but some partial tears can be managed with stenting and/or observation. When a UPJ injury is undiagnosed and when the proximal collecting system is not drained, a urinoma can develop. This may lead eventually to the need for nephrectomy. [30, 31, 32]

-

Illustration shows the spaces around the kidney and fascial landmarks that are important in differentiating the grades of injury and pattern of hemorrhage spread. Grade I hematomas do not extend beyond the renal capsule. Grade II hematomas can extend beyond the renal capsule but not beyond the Gerota fascia. Both grades I and II remain confined to the perirenal space. Grade III, IV, and V injuries can involve disruption of the Gerota fascia and extension into the pararenal space.

-

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade I kidney injury are subcapsular hematoma (arrowhead) not extending beyond the renal capsule and/or parenchymal contusion (arrow) without laceration.

-

Grade I injury: contusion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows an ill-defined area of decreased enhancement in the right kidney representing a renal contusion. This must be differentiated from a more serious grade IV peripheral segmental infarction, which shows as lack of enhancement rather than decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Note the well-defined outer margin, which denotes that the hematoma is contained within the Gerota fascia. This must be differentiated from grade III and higher injuries, which can extend beyond the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade I injury: subcapsular hematoma, Page kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a crescent-shaped high-density fluid collection around the left kidney. Mild deformity of the renal parenchyma caused by the hematoma is evident. Note that if a subcapsular hematoma becomes large enough, it can take a lentiform shape rather than a crescent shape. This is important, since larger subcapsular hematomas compressing the renal parenchyma may cause a hypertensive phenomenon known as Page kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade II kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration ≤1 cm in depth (arrow) without urinary extravasation and/or perirenal hematoma confined by Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. There is also a laceration measuring less than 1 cm deep. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. There is a subtle 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole posterolateral cortex, best seen on the next image obtained in the coronal plane. If the laceration depth measured greater than 1 cm, the injury would be classified as grade III.

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a small left perirenal hematoma without extension beyond the Gerota fascia. The 1 cm laceration in the left lower pole is better seen on this coronal plane.

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after a motor vehicle accident shows a questionable area of decreased renal attenuation in the left upper pole as seen on this axial plane, which was initially thought to represent a streak artifact caused by the patient's arms at the sides. The next image shows the laceration in the sagittal plane which corresponds to the same location. There is a very small adjacent perirenal hematoma. This case illustrates the importance of carefully inspecting the images when degraded by such artifacts.

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma, 1 cm or less laceration. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above better demonstrates the area of decreased renal attenuation on this sagittal plane. The laceration can clearly be seen in the upper pole corresponding to the same location as the axial plane.

-

Grade II injury: perirenal hematoma. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows a large hematoma outside the renal capsule but still contained within the perirenal space inside the Gerota fascia. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan to exclude contrast extravasation outside the collecting system. If urinary contrast extravasation was found, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Also notice that despite the large size of the hematoma, there is no deformity of the kidney as seen with large subcapsular hematomas. This feature helps to distinguish the location of the hematoma as either subcapsular or perirenal. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Criteria for American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) grade III kidney injury are renal parenchymal laceration > 1 cm in depth (arrow), without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation; and/or any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury (pseudoaneurysm; curved arrow) or active bleeding contained within Gerota fascia (arrowhead).

-

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a laceration greater than 1 cm in depth (measured from cortex into parenchyma) with an associated perirenal hematoma. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia in the perirenal space. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade III injury: > 1 cm laceration, perirenal hematoma. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows no urinary extravasation from the collecting system. If the laceration extended deeper into the collecting system with urinary extravasation, it would be classified as a grade IV injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade III injury: perirenal hematoma with active bleeding. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a perirenal hematoma. There is a small collection of contrast within the hematoma consistent with active bleeding. The hematoma remains inside the Gerota fascia. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) defines grade IV kidney injury by the presence of at least one of the following: -Parenchymal laceration extending into the collecting system with urinary extravasation (arrowhead) -Renal pelvis laceration and/or complete ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) disruption (arrow) -Segmental renal vein or artery (arrowhead) injury with (purple) or without infarction -Active bleeding beyond Gerota fascia into the retroperitoneal space or peritoneal cavity (dashed arrow) -Segmental or complete kidney infarction due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding

-

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a well-defined triangular area of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important to avoid a potential pitfall by calling this a contusion which would downgrade the injury to a grade 1 injury and alter appropriate management. Infarctions are typically well-defined with lack of enhancement while contusions are typically ill-defined with decreased enhancement. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade IV injury: segmental infarction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows another example of segmental infarction. There are two small but well-defined triangular areas of non-enhancement in the left kidney consistent with segmental infarction. It is important not to mistakenly classify this as grade 1 renal laceration since both infarctions and lacerations are typically peripheral. Lacerations tend to be more linear than triangular. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade IV injury: urinary extravasation. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA show extensive urinary contrast extravasation from a deep laceration. This case demonstrates the importance of a delayed scan in evaluating for injury at the renal pelvis and uretero-pelvic junction (UPJ). Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows normal enhancement of the right kidney with fluid around the UPJ mimicking a perirenal hematoma. Delayed scan on the next image reveals significant UPJ injury. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade V renal injury: UPJ ureteral avulsion. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above reveals significant urinary contrast extravasation from UPJ ureteral avulsion. Complete avulsion at the hilum would have resulted in a devascularized kidney in addition to the urinary extravasation at the UPJ. When fluid is located medially near the renal hilum, ureteral injury should be suspected. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade V renal injury: devascularized kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after assault shows dissection of the left renal artery near the origin with lack of enhancement in the kidney. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after motor-pedestrian accident shows complete lack of enhancement in the right kidney and only single segment enhancement in the right kidney from bilateral vascular injury near the renal hila.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery and vein injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows subsequent placement of a vascular stent which resulted in improved left renal enhancement.

-

Grade V renal injury: shattered kidney. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows multiple deep lacerations and loss of normal parenchymal anatomy consistent with a shattered kidney. There is thrombus in the inferior vena cava extending from a thrombus in the renal vein. Courtesy of J Kevin Smith, MD, PhD.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in a patient after MVA shows no laceration but only minimal stranding around the left renal hilum and a thin halo surrounding the left main renal artery on this early phase.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 3-minute delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan in the same patient as above shows asymmetrically decreased enhancement of the left kidney with a persistent nephrogram phase compared to the normal right. Renal hilar injury was suspected prompting a further delayed scan as shown in the next image.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A 45-minute delayed scan in the same patient as above reveals IV contrast in the ureter without urinary extravasation, but the halo around the renal artery remains. A reconstructed sagittal scan shown in the next image reveals injury to the left renal artery.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. On this sagittal plane scan, a subtle defect (arrow) is seen in the renal artery consistent with arterial injury. Follow-up angiogram on the next image reveals the extent of the injury.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. Follow-up angiogram reveals a small dissection flap in the left renal artery and a small contained perforation.

-

Grade V renal injury: main renal artery injury. A stent was subsequently placed through the injured segment of the left renal artery.

-

AAST Grade V (at least one finding below): -Main renal artery or vein laceration (curved arrow) or avulsion of the hilum (dashed arrow and line). -Devascularized kidney with active bleeding. -Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal anatomy.