Overview

Nasal bone fractures are among the most common facial bone fractures. [1] According to several retrospective studies, nasal bone fractures comprise up to 50% of all facial fractures. The prototypical patient is a male aged 15-30 years who was involved in a fight, motor vehicle accident, or fall. [2]

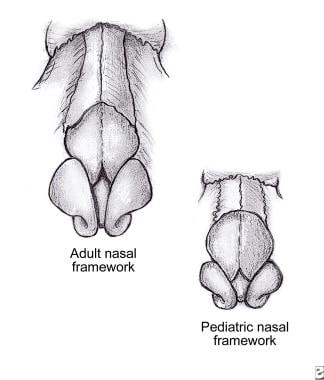

Practitioners must understand the anatomy of the nasal bones before attempting any manipulation. The paired nasal bones project from the frontal processes of the maxilla, superiorly from the nasal process of the frontal bone, and join in the midline (see the image below). The quadrangular, or septal, cartilage supports the nasal bones from below.

The lateral nasal walls contain 3 pairs each of small, thin, shell-like bones: the superior, middle, and inferior conchae, which form the bony framework of the turbinates. Lateral to these curved structures lies the medial wall of the maxillary sinus. For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Nasal Anatomy.

Approximately 80% of nasal fractures occur between the thicker proximal and thinner distal segments of the nasal bones. Although frontal impact can cause fracture of the nasal bones, lateral impacts are more common. These lateral impact injuries typically cause a depression of one nasal bone and may result in a lateral displacement of the contralateral nasal bone. [2]

Diagnosis

See the list below:

-

Most nasal fractures are diagnosed by history and physical examination.

-

History usually includes a preexisting trauma, which may be followed by epistaxis. Typically, the epistaxis has resolved by the time the patient presents for intervention.

-

Patients usually present with swelling over the nasal bridge and a difference in the appearance or shape of the nose.

-

Physical examination findings include swelling over the nasal bridge, grossly apparent deviation of the nasal bones, and periorbital ecchymosis.

-

Plain radiographs are not helpful in the diagnosis or management of nasal fractures in isolated nasal injury. [3]

-

Nasal bone CT scan is helpful if the patient has associated facial fractures. [4]

-

Be sure to ask the patient how the external shape of the nose has changed since the fracture. This helps determine what corrective maneuvers should be taken to restore the patient’s appearance through reduction of the nasal fracture.

Indications

See the list below:

-

Simple fracture of the nasal bones or nasal-septal complex

-

Nasal obstruction or airway compromise from deviated nasal bones

-

Fracture of the nasal-septal complex with nasal deviation less than one half the width of the nasal bridge [5]

-

Reduction less than 3 hours after injury in adults and children (if minimal edema is present)

-

Reduction 6-10 days after injury in adults (after edema has resolved and before the setting of fracture fragments) [6]

-

Reduction 3-7 days after injury in children (after edema has resolved and before the setting of fracture fragments)

Contraindications

See the list below:

-

Severe comminution of the nasal bones and septum

-

Associated orbital wall or ethmoid bone fractures [2]

-

Nasal pyramid deviation that exceeds one half the width of the nasal bridge

-

Caudal septum fracture dislocation

-

Open septal fractures

-

Fractures examined 3 weeks or longer after the injury occurred

Anesthesia

Topical local anesthesia with vasoconstriction

Soak pledgets in oxymetazoline (Afrin), phenylephrine (Neo-synephrine), or lidocaine 1-2% with epinephrine 1:100,000. For vasoconstriction along with the use of infiltrative local anesthetic agents, see below.

Place 1 pair of pledgets inside the nasal cavity (lying beneath the nasal dorsum, along the septum, and on the floor of the nose). See the image below.

Remove pledgets after 10-15 minutes.

Local anesthetic infiltration

A solution of 1% or 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine is injected bilaterally in the following locations:

-

Along and beneath the soft tissue of the nasal dorsum (to anesthetize infratrochlear nerves)

-

Into the area of the infraorbital foramen (to anesthetize infraorbital nerves)

-

At the base of the columella and along the floor of the nasal cavity (See the image below.)

For more information, see Local Anesthetic Agents, Infiltrative Administration.

Equipment

See the image below.

Equipment for nasal fracture reduction (clockwise from bottom left): nasal speculum, anesthetic for infiltration, anesthetic solution for pledgets, nasal pledgets, elevator, Asch forceps, sterile gloves.

Equipment for nasal fracture reduction (clockwise from bottom left): nasal speculum, anesthetic for infiltration, anesthetic solution for pledgets, nasal pledgets, elevator, Asch forceps, sterile gloves.

See the list below:

-

Good light source

-

Frazier suction

-

Nasal speculum

-

Bayonet forceps

-

Pledgets (quarter-inch nasal cotton pledgets)

-

Merocel

-

Elevators (Goldman/Boies/Salinger/Ballenger)

-

Walsham forceps (for grasping nasal bones)

-

Asch forceps (for septum reduction)

-

External splint (Thermoplast/Aquaplast)

-

Intranasal cocaine solution

-

Infiltration lidocaine solution with epinephrine

-

Needle, 27 gauge or smaller

-

Syringe, 3 mL

Positioning

See the list below:

-

The practitioner and patient should each be in a position of comfort.

-

A sitting or recumbent position with head elevated is usually tolerated well.

-

C-spine precautions take precedence over comfort.

Technique

Nasal pyramid fractures should be reduced first, followed by nasal septum reduction. [7, 8, 9]

Explain the risks, benefits, and alternatives to the patient. Obtain a signed informed consent, if possible.

Deliver appropriate anesthesia. For details, see Anesthesia.

To reduce nasal pyramids, measure the distance from the alar rim to the depressed fragment externally. Mark position with thumb. Reduce depressed side of nose first.

Insert Boies or Salinger elevator into the nose under the depressed fragment. Apply steady outward pressure on the posterior aspect of the nasal bone. Control outward pressure with counterpressure exteriorly with the other thumb. Fragments may need to be molded into the proper position.

If unable to reduce with elevators, use Walsham forceps to directly grasp the nasal bone. Insert one blade beneath the bone as the other blade is opposed on the outer skin surface. Manipulate the bone into position.

Check for septal reduction. If not adequately reduced, use Asch forceps to elevate the nasal pyramid while applying direct pressure to the displaced portion of the septum until it is moved back into the proper position.

Check for septal hematoma (drain if present).

Stabilize reduction with internal packing (eg, Vaseline gauze or 8-cm Merocel) and an external splint (eg, Thermaplast, Aquaplast). These external splints require intense heat for activation and molding, so the nasal dorsal skin should be protected with Steri-Strip bandage application prior to placement of the splint.

Remove packing in 5 days and remove nasal splint in 7 days. While the nasal packing is in place, the patient should be on an oral antibiotic with adequate Staphylococcus aureus coverage (eg, cephalexin) in order to prevent sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome.

See the images below.

Pearls

See the list below:

-

Routine radiography is not necessary for diagnosis and management of nasal fracture.

-

Optimal timing for reduction varies.

If patient presents with a recent injury and minimal edema, the optimal timing for reduction is within 3 hours of the injury (in both adults and children).

If edema is significant, delay reduction until after edema has resolved but before the setting of fracture fragments (6-10 d after injury in adults; 3-7 d after injury in children).

-

Referral to an ENT specialist or plastic surgeon is mandatory.

-

Remember to check for septal hematomas before and after the procedure.

-

Antibiotic prophylaxis is necessary for intranasal packing.

Complications

See the list below:

-

Inability to reduce: Fractures that cannot be reduced via closed reduction are candidates for open reduction. [10] Open reduction, in most cases, should be delayed until approximately 3 months after injury in order to allow for complete resolution of swelling and settling of the nasal and cartilaginous fragments. This resolution allows for a more accurate evaluation of the pathology, and, therefore, a better cosmetic result after intervention such as open septorhinoplasty. [11]

-

Septal hematoma: Bleeding in the subperichondrial plane of the septum can lift the perichondrium off of the cartilage and disrupt its blood supply. This disruption may cause irreversible damage to the underlying nasal cartilage within 3-4 days and may eventually result in a saddle nose deformity. Once detected, drain the septal hematoma immediately with several small incisions in the mucoperichondrium. Septal splints or intranasal packing should be used to prevent reaccumulation. [4]

-

Hemorrhage: Despite application of topical vasoconstrictors, excessive bleeding may occur. Direct pressure and intranasal packing is the treatment of choice. Coagulation studies may be indicated to detect patients who have bleeding diatheses. Laboratory tests for excessive blood loss may be indicated.

-

Dysesthesia: Direct infiltration of local anesthesia carries the risk of nerve damage and may result in minor dysesthesias or paresthesias after the effects of the anesthetic diminish.

-

Infection: Placement of intranasal packing may result in the development of sinusitis, or, less commonly, a toxic shock – like infection; provide adequate antibiotic prophylaxis. Preprocedural prophylaxis should be given to patients with coronary valvular disease.

-

Nasal bone anatomy.

-

Equipment for nasal fracture reduction (clockwise from bottom left): nasal speculum, anesthetic for infiltration, anesthetic solution for pledgets, nasal pledgets, elevator, Asch forceps, sterile gloves.

-

Nasal pledget placement.

-

Intranasal anesthetic infiltration.

-

Nasal bone reduction.

-

Septal reduction with forceps.