Overview

The ability to care for dental fractures in the emergency department or clinic setting is a skill required during the career of every clinic-based or emergency clinician. Although the procedures performed in these settings are largely temporizing measures, appropriate care in the acute setting is critical to avoid adverse outcomes. Limiting factors to the appropriate care of dental fractures in the emergency department setting include lack of knowledgeable and willing on-call dental professionals 24 hours a day and a lack of knowledge, experience, and focused training of emergency physicians in the care of dental injuries. [1]

In general, acute dental trauma is inadequately treated. In some patient populations, less than half of patients who need treatment receive it; of those who do receive treatment, over half receive inadequate treatment. Many patients with acute dental trauma require follow-up with a dentist or an oral surgeon within 24 hours; however, proper intervention should not be delayed. These procedures can improve cosmetic results, prevent tooth loss, and decrease the risk of infection following dental trauma.

Dental fractures are divided into categories based on the Ellis classification system.

-

Ellis I: This level of injury includes crown fractures that extend through the enamel only. These teeth are usually nontender and without visible color change but have rough edges.

-

Ellis II: Injuries in this category are fractures that involve the enamel as well as the dentin layer. These teeth are typically tender to the touch and to air exposure. A yellow layer of dentin may be visible on examination.

-

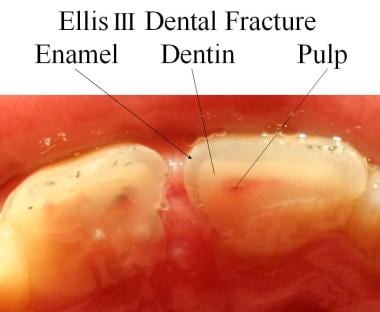

Ellis III: These fractures involve the enamel, dentin, and pulp layers. These teeth are tender (similar to those in the Ellis II category) and have a visible area of pink, red, or even blood at the center of the tooth.

The pulp of the tooth is very prone to infection. Infection of the pulp is termed pulpitis and can lead to potential tooth loss. The dentin of the tooth is very porous and is an ineffective seal over the pulp. In Ellis II and III fractures in which the dentin or pulp is exposed, the clinician caring for the tooth fracture in the acute setting must create a seal over these injured teeth to protect the pulp from intraoral flora and potential infection.

Other dental injuries that may or may not be associated with a dental fracture include the following:

-

Dental avulsion - Complete extraction of the tooth (crown and root)

-

Dental subluxation - The loosening of a tooth following trauma

-

Dental intrusion - The forcing of an erupted tooth below the gingiva

In these situations, the goal is to return the tooth to its correct anatomical position as quickly and securely as possible, without causing further trauma to the tooth, gingiva, or alveolar bone.

An estimated 50% of children sustain a dental injury before age 18 years; most children are aged 7-14 years at the time of injury. Permanent teeth injuries make up 90% of the dental injuries to children; the most commonly injured teeth are the central incisors.

Dental trauma has a male predominance of almost 2:1. This predominance is evident in permanent dentition but not in the setting of primary dentition. Dental fractures are most common in children, youth, and young adults. Dental fracture is often a result of falls, play, altercations, sports, and motor vehicle accidents. [2, 3] A Korean study found that among the most common risk factors for tooth fracture are failure to wear a seatbelt in a motor vehicle, failure to wear a helmet while riding a motorcycle or bicycle, and injuries associated with the use of earphones and smartphones. [4]

A retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project found that between 2008 and 2010, a total of 199,061 emergency department visits were attributed to broken or fractured teeth and that males comprised 63% percent of emergency department visits. [5]

Relevant anatomy

The tooth anatomy includes the crown, which is the portion of the tooth exposed to the oral cavity, and one or more roots, which are enveloped in bone and the periodontium.

In the transverse section, the tooth has 3 distinct layers, as follows:

-

A surface enamel layer covering only the crown

-

An inner layer of dentin in both the crown and the root

-

The core area, known as the pulp, which contains nerves, arteries, and veins

Radiographically, the layers are easily identifiable because they have different radiopacities. Enamel is the most mineralized of the calcified tissues of the body, and it is the most radiopaque of the 3 tooth layers. Dentin is less radiopaque than enamel and has a radiopacity similar to that of bone. The pulp tissue is not mineralized and appears radiolucent.

For more information about the relevant anatomy, see Tooth Anatomy.

Indications

The treatment of the following dental fractures should be performed in the setting of acute dental trauma [6] :

-

Ellis I fracture

-

Ellis II fracture

-

Ellis III fracture

-

Subluxation

-

Avulsion-type injury

Contraindications

Consider the risk of aspiration [7] prior to arrival or following repair in the following specific subgroups of patients:

-

Intoxicated

-

Altered mental status

-

Decreased functional capacity

-

Significant facial trauma

In multisystem trauma patients, always address the more critical issues and injuries first.

Tooth extraction may be a viable option in some cases of primary tooth injuries.

Anesthesia

Anesthetic options include the following:

-

Local anesthesia at the tooth apex

-

Topical anesthetics should be avoided.

Equipment

Most essential equipment is available in a prepacked dental tray or dental box.

-

Local parenteral anesthetic agent (eg, lidocaine [Xylocaine], bupivacaine [Marcaine])

-

Zinc oxide topical ointment or cream

-

Calcium hydroxide composition (Dycal)

-

Glass ionomer composite

-

Cotton-tipped applicator or dental tools

-

Aluminum foil

-

Antibiotic agent (eg, penicillin V, clindamycin, erythromycin)

-

Tetanus toxoid vaccine booster dose

Positioning

Seat the patient in a reclined position at a 30-60° angle.

The patient’s neck should be slightly hyperextended.

A dental chair provides ideal support for the desired position.

The ability to position the patient may be limited because of the spine precautions necessary in patients with multisystem or isolated head or neck trauma.

Technique

Ellis class I

1. File down sharp edges, if necessary, with a dental drill or emery board.

2. Dental follow-up, as desired by the patient, is for cosmetic purposes only.

Ellis class II

1. Cover the exposed surface with a calcium hydroxide composition (eg, Dycal), a glass ionomer, or a strip of adhesive barrier (eg, Stomahesive). 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond) has been shown to be an acceptable alternative in the setting of a dental fracture if no other materials are available. [8] The 2-octyl cyanoacrylate decreases tooth sensitivity and provides a protective barrier until dental follow-up. [9]

2. Provide pain medications.

3. Instruct the patient to avoid hot and cold food or drink.

4. Arrange for a follow-up appointment with a dentist within 24 hours.

5. Consider antibiotic coverage with penicillin or clindamycin.

Ellis class III

1. Cover the exposed surface with a calcium hydroxide composition (eg, Dycal) or a glass ionomer.

2. Provide immediate dental follow-up and analgesics as needed.

3. Initiate antibiotics with coverage of intraoral flora (eg, penicillin, clindamycin).

Dental avulsion

1. An avulsed tooth may be gently cleansed in either normal saline or sterile auxiliary solution (eg, Hank's balanced salt solution).

2. Avoid scrubbing the tooth or any unnecessary delay before reimplantation.

3. The tooth can be returned to its original position by applying firm finger pressure.

4. Handle the tooth by the crown, and avoid trauma to the tooth root.

5. Stabilize the tooth with a temporary periodontal splint.

6. Provide early dental follow-up.

7. Initiate antibiotics with coverage of intraoral flora (eg, penicillin, clindamycin).

8. If the avulsed tooth or fracture fragment is not located, assess any lip laceration for a retained foreign body and consider aspiration as a possibility. [7]

Dental subluxation

1. This type of injury may not require emergency treatment.

2. Very loose teeth should be pressed back into their sockets.

3. They should then be stabilized with wire or a temporary periodontal splint (eg, Coe-Pak).

4. Patients with dental subluxation should maintain a soft or liquid diet to prevent further tooth motion.

5. Provide early dental follow-up.

6. Initiate antibiotics with coverage of intraoral flora (eg, penicillin, clindamycin).

Dental intrusion

1. These injuries can be left alone and allowed to re-erupt.

2. Provide early dental follow-up.

3. Initiate antibiotics with coverage of intraoral flora (eg, penicillin, clindamycin).

Pearls

Pearls for the management of fractured teeth are as follows:

-

Pediatric patients (aged < 12 y) have a thinner layer of dentin to protect the pulp. As a result, Ellis II fractures are more likely to become infected and should be treated as Ellis III fractures in this patient population.

-

Update the patient’s tetanus vaccination, if necessary.

-

Instruct patients to eat only soft foods following all injuries (except an Ellis I fracture).

-

Always consider the possibility of abuse (eg, child, spousal, or elder abuse) when patients present with dental fractures.

-

Complete a physical examination of the bony structures of the face when indicated to ensure that a more serious injury (eg, Le Fort fracture) is not missed.

-

Examine all intraoral lacerations for tooth fragments, which can result in chronic infections. For information on the treatment of intraoral lacerations, see Medscape Reference articles Complex Lip Laceration and Complex Tongue Laceration.

-

Avoid topical anesthesia, as it can increase the risk of a sterile abscess and irritation.

-

Dental blocks are very useful for pain control.

-

If teeth or partial teeth are missing, obtain a radiograph of the chest to rule out pulmonary aspiration [7] or a CT scan of the face to rule out intrusion into alveolar bone or gingiva.

-

All dental fractures (except for Ellis I) require dental follow-up within 24 hours.

Complications

Complications include the following:

-

Loss of tooth

-

Infection or abscess

-

Aspiration of partial or whole tooth

-

Cosmetic deformity

-

Cross section of an Ellis III dental fracture.

-

The use of calcium hydroxide composition (Dycal).