Overview

Background

Meconium is a viscous green-black substance that consists of denuded intestinal epithelial cells, ingested lanugo hair, mucus, digestive enzymes, bile acids, and water. The term meconium is derived from the Greek word mekonion, which means poppy juice or opium, presumably either because of its tarry appearance or because of Aristotle's belief that it induced sleep in the fetus.

Meconium constitutes the first stool of a newborn infant. The passage of meconium typically occurs within 48 hours after birth; however, it can occur in utero. Postterm fetus may pass the meconium physiologically. Intrauterine meconium passage has been linked to fetal hypoxia and is associated with fetal acidosis, abnormal fetal heart tracings, and low Apgar scores. [1]

In preterm pregnancies, intrauterine meconium passage has been associated with fetomaternal stress and infection. [2] In term and postterm infants without fetal distress, intrauterine meconium passage may result from normal gastrointestinal (GI) maturation or from vagal stimulation caused by head or cord compression. [3] Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid occurs in approximately 13% of live births; this percentage increases with increasing gestational age at delivery. [3]

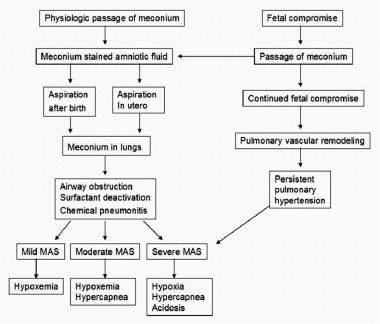

Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) occurs when meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) is aspirated into the lungs of an infant before, during, or immediately after birth (see the image below). [4] Intrauterine gasping, resulting in aspiration of meconium, has been demonstrated in animal models exposed to hypoxia. [5, 6, 7] MAS occurs in approximately 5% of infants born through MSAF. [3] Even with modern neonatal intensive care, mortality from MAS remains high, in the range of 3-5%. [1, 8]

Pathophysiology of meconium aspiration. Image adapted from Wiswell T, Bent RC. Meconium staining and the meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40(5):955-981.

Pathophysiology of meconium aspiration. Image adapted from Wiswell T, Bent RC. Meconium staining and the meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40(5):955-981.

Many perinatal risk factors have been associated with meconium aspiration, including placental insufficiency, maternal hypertension, maternal diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, oligohydramnios, and maternal tobacco use. [3, 9, 10] Perhaps the most significant risk factor, however, is postterm delivery. In a prospective clinical study, a decrease in the incidence of MAS from 5.8% to 1.5% over an 8-year period was attributed to a reduction in births at more than 41 weeks' gestation. [11]

MAS occurs along a continuum from mild to severe. [12] Mild MAS is seen in infants born through MSAF who have mild respiratory symptoms; it probably reflects mild parenchymal irritation from aspirated meconium. Moderate MAS presents with more pronounced pulmonary symptoms, including moderately high oxygen requirements and a possible need for mechanical ventilation; it may reflect a more significant meconium load or the aspiration of thicker meconium into the lungs. [12]

Infants with severe MAS require mechanical ventilation with high settings and may need alternative therapies, such as inhaled nitric oxide (NO) and, possibly, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). [13] These cases probably represent a combination of meconium aspiration and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). PPHN in these cases is thought to arise from chronic fetal compromise (hypoxia) with resultant pulmonary vascular remodeling. PPHN further contributes to the hypoxemia associated with MAS. [14]

There is evidence to suggest that chronic in utero hypoxia with resultant PPHN, rather than the aspiration of meconium per se, may be the primary pathologic problem in newborn infants diagnosed with severe MAS. [15, 16]

Guidelines for the management of infants born through MSAF

-

Infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid, regardless of whether they are vigorous or not, should no longer routinely receive intrapartum suctioning. However, meconium-stained amniotic fluid is a condition that requires the notification and availability of an appropriately credentialed team with full resuscitation skills, including endotracheal intubation.

-

Resuscitation should follow the same principles for infants with meconium-stained fluid as for those with clear fluid.

American Heart Association Guidelines on Neonatal Resuscitation [19]

-

For nonvigorous newborns (presenting with apnea or ineffective breathing effort) delivered through MSAF, routine laryngoscopy with or without tracheal suctioning is not recommended.

-

For nonvigorous newborns delivered through MSAF who have evidence of airway obstruction during positive pressure ventilation (PPV), intubation and tracheal suction can be beneficial.

The ACOG recommendation to avoid routine tracheal suction in nonvigorous infants arose from an emphasis on prevention of harm (ie, delays in providing bag-mask ventilation and potential consequences of unnecessary interventions) instead of the unknown benefit of the interventions of routine tracheal intubation and suctioning. [17] This recommendation was reaffirmed in 2021. [18] Supporting evidence for the 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines was a meta-analysis suggesting that non-vigorous newborns delivered through MSAF have the same outcomes (survival, need for respiratory support, or neurodevelopment) whether they are suctioned before or after the initiation of PPV. [20]

Technical Considerations

Best practices

Several procedures have been used in the past to prevent MAS; none are supported by strong evidence of proven benefit.

Several other preventive measures that were commonly used in the past to prevent MAS, including amnioinfusion and intrapartum oronasopharyngeal suctioning, have now been largely abandoned as a result of findings from randomized, controlled trials.

Amnioinfusion involves the infusion of isotonic fluid (either normal saline or lactated Ringer solution) into the amniotic cavity via a transcervical intrauterine pressure catheter in an attempt to dilute the MSAF. The results of previous trials using amnioinfusion to prevent MAS have been mixed. However, given the heterogeneity of the studies and the small number of patients in each study, results must be interpreted with caution. [1]

A 2002 Cochrane review concluded that amnioinfusion was effective in reducing the incidence of MAS, especially in centers where perinatal surveillance was limited [21] ; however, a 2010 update of this study found that substantive improvements in perinatal outcome were restricted to settings where facilities for perinatal surveillance are limited. [22] In a multinational, multicenter, randomized controlled trial involving 1998 women with thick MSAF, amnioinfusion had no significant effect on the incidence of MAS or death. [23] More recently, the results of a meta-analysis by Davis et al support amnioinfusion to prevent MAS; their data showed that amnioinfusion has helped reduce the incidence of MAS by 67%. [24]

These findings and the supposition that a large number of infants born through MSAF will have aspirated meconium before amnioinfusion can be performed prompted an ACOG opinion stating that "routine prophylactic amnioinfusion for the dilution of meconium-stained amniotic fluid should be done only in the setting of additional clinical trials." [25] In this same statement, however, the ACOG noted that "amnioinfusion remains a reasonable approach in the treatment of repetitive variable decelerations, regardless of amniotic fluid meconium status." [25]

In a randomized controlled trial involving 2514 full-term women with MSAF, Vain et al did not find intrapartum suctioning with a suction catheter to have a beneficial effect on need for endotracheal intubation, incidence of MAS, need for mechanical ventilation, and neonatal mortality. [26] The ACOG now recommends that "infants with MSAF should no longer receive intrapartum suctioning. [27]

Because meconium aspiration can occur before delivery as a consequence of chronic asphyxia and infection, perhaps the most important strategy for preventing MAS is good prenatal care, including the detection and prevention of fetal hypoxemia and the avoidance of postterm deliveries.

Periprocedural Care

Equipment

The equipment required to suction the trachea of a newborn with airway obstruction from meconium aspiration includes the following:

-

Laryngoscope with blade (size 1 for a term infant)

-

Uncuffed endotracheal tube (size 3.5-4.0 for a term infant)

-

DeLee suction catheter (12-14 French)

-

Meconium aspirator

-

Suction tubing

-

Medical suction device set to a continuous pressure of –80 to –120 mm Hg

Patient Preparation

For nonvigorous newborns delivered through MSAF who have evidence of airway obstruction during positive pressure ventilation (PPV), intubation and tracheal suction can be beneficial. Airway obstructed during PPV is detected by no air entry into the lungs, no chest wall movement, and no heart rate rise with face mask PPV. Additionally, if intubation or placement of a supraglottic airway device is performed and there is still no air entry into the lungs, no chest wall movement, and no heart rate rise, then a distal tracheal obstruction with meconium should be considered.

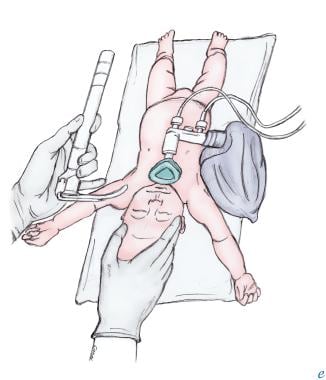

If the trachea is obstructed with meconium, then endotracheal intubation and suctioning is required to have successful resuscitation. For intubation and tracheal suctioning, the infant should be placed on a flat surface, ideally under a radiant warmer. The head should be in midline position, with the neck slightly extended into the so-called sniffing position (see the image below). Placing a roll of towels under the infant’s shoulders may help maintain slight neck extension. Do not flex or hyperextend the neck; this raises the glottis above the line of sight and makes intubation more difficult. Caution should be exercised to limit the amount of time required for endotracheal intubation, as the infant is not being ventilated during that time and not receiving effective ventilation.

Technique

Intubation and Tracheal Suctioning

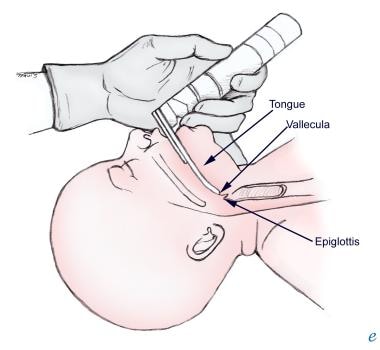

Hold the laryngoscope in the left hand, and stabilize the infant's head with the right hand. Introduce the laryngoscope blade into the right side of the mouth, and sweep the tongue to the left with the laryngoscope blade. To make introduction of the laryngoscope blade easier, try using the right index finger to open the newborn’s mouth. Advance the laryngoscope blade until the tip is positioned on top of the epiglottis or immediately anterior to the epiglottis in the vallecula (see the image below).

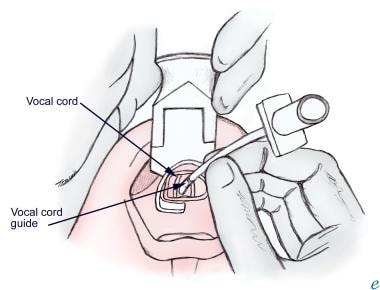

Gently lift the laryngoscope blade upward to elevate the epiglottis and tongue to reveal the vocal cords (see the image below). Do not "rock back" with the laryngoscope blade; doing so may damage the alveolar ridge. Identify the vocal cords, and attempt to verify the presence of meconium below the level of the cords. If meconium is present, the posterior pharynx may have to be suctioned with a DeLee suction catheter to improve visualization of the cords.

Maintain direct visualization of the vocal cords as an assistant places the endotracheal tube into your right hand. Advance the endotracheal tube through open vocal cords until the vocal cord guide on the endotracheal tube is at the level of the cords (see the image below). If the vocal cords are approximated, wait for them to open. Do not force the endotracheal tube through closed vocal cords; doing so can damage the cords.

Stabilize the endotracheal tube in position by using an index finger to hold the tube against the hard palate. While holding the endotracheal tube in place, remove the laryngoscope blade. Ideally, the entire process of tracheal intubation should take less than 20 seconds. [28]

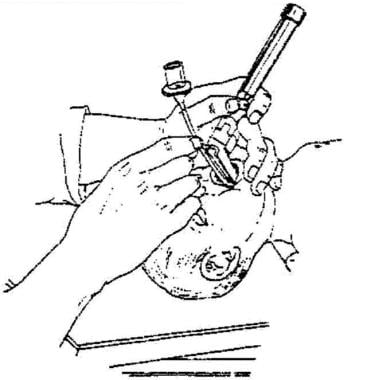

Attach a meconium aspirator [29] , connected to a medical suction device supplying a continuous pressure of –80 to –120 mm Hg, to the endotracheal tube. Occlude the suction-control port on the meconium aspirator to apply suction (see the image below).

While applying suction, withdraw the endotracheal tube over a period of 3-5 seconds. If a substantial amount of meconium is returned by suction, intubation and suction should be repeated quickly or the newborn’s heart rate falls below 100 beats/min. If the heart rate is falling and infant is limp, endotracheal tube should be removed if it is significantly stained with meconium otherwise PPV should be provided through that endotracheal tube and rest of the resuscitation steps as per NRP.

Complications of Procedure

Complications of intubation and tracheal suctioning include the following:

-

Trauma to lips, alveolar ridge, and tongue

-

Laryngospasm

-

Bronchospasm

-

Laryngeal trauma

-

Vocal cord injury or avulsion

-

Fractures and dislocation of arytenoids

-

Airway perforation

-

Esophageal intubation

-

Bronchial intubation

-

Bradycardia

-

Hypotension

-

Regurgitation of gastric contents

-

Pathophysiology of meconium aspiration. Image adapted from Wiswell T, Bent RC. Meconium staining and the meconium aspiration syndrome. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40(5):955-981.

-

Intubation of trachea.

-

Use of meconium aspirator.

-

Positioning of infant for intubation.

-

Laryngoscope blade tip in vallecula.

-

Visualization of vocal cords during intubation.