Practice Essentials

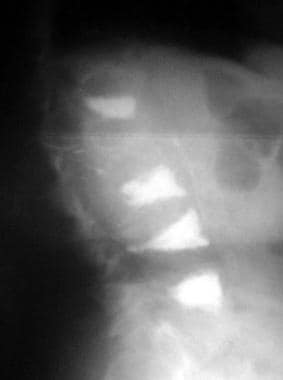

Osteoporosis, in which low bone mass and micro-structural deterioration of bone tissue lead to increased bone fragility, is the most common metabolic bone disease in the United States. [1, 2] Osteoporosis can result in devastating physical, psychosocial, and economic consequences. Still, it is often overlooked and undertreated, in large part because it is clinically silent; there are no symptoms before a fracture occurs. (See the image below.)

Osteoporosis of the spine. Observe the considerable reduction in overall vertebral bone density and note the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

Osteoporosis of the spine. Observe the considerable reduction in overall vertebral bone density and note the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

Signs and symptoms

Osteoporosis does not become clinically apparent until a fracture occurs and so is sometimes referred to as the “silent disease.” Two-thirds of vertebral fractures are painless, although patients may complain of the resulting stooped posture and height loss. Typical findings in patients with painful vertebral fractures may include the following:

-

The episode of acute pain may follow a fall or minor trauma.

-

Pain is localized to a specific, identifiable, vertebral level in the midthoracic to lower thoracic or upper lumbar spine.

-

The pain is described variably as sharp, nagging, or dull; movement may exacerbate pain; in some cases, pain radiates to the abdomen.

-

Pain is often accompanied by paravertebral muscle spasms exacerbated by activity and decreased by lying supine.

-

Patients often remain motionless in bed because of fear of exacerbating the pain.

-

Acute pain usually resolves after 4-6 weeks; in the setting of multiple fractures with severe kyphosis, the pain may become chronic.

Patients who have sustained a hip fracture may experience the following:

-

Pain in the groin, posterior buttock, anterior thigh, medial thigh, and/or medial knee during weight-bearing or attempted weight-bearing of the involved extremity

-

Diminished hip range of motion (ROM), particularly internal rotation and flexion

-

External rotation of the involved hip while in the resting position

On physical examination, patients with vertebral compression fractures may demonstrate the following:

-

With acute vertebral fractures, point tenderness over the involved vertebra

-

Thoracic kyphosis with an exaggerated cervical lordosis (dowager's hump)

-

Subsequent loss of lumbar lordosis

-

A decrease in the height of 2-3 cm after each vertebral compression fracture and progressive kyphosis

Patients with hip fractures may demonstrate the following:

-

Limited ROM with end-range pain on a FABER (flexion, abduction, and external rotation) hip joint test

-

Decreased weight-bearing on the fractured side or an antalgic gait pattern

Patients with Colles fractures may have the following:

-

Pain on movement of the wrist

-

Dinner fork (bayonet) deformity

Patients with pubic and sacral fractures may have the following:

-

Marked pain with ambulation

-

Tenderness to palpation, percussion, or both

-

With sacral fractures, pain with physical examination techniques used to assess the sacroiliac joint (eg, FABER, Gaenslen, or squish test)

Balance difficulties may be evident, especially in patients with an altered center of gravity from severe kyphosis. [3] Patients may have difficulty performing tandem gait and performing single-limb stance.

See the Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Baseline laboratory studies include the following:

-

Complete blood count: May reveal anemia

-

Serum chemistry levels: Usually normal in persons with primary osteoporosis

-

Liver function tests

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone level: Thyroid dysfunction has been associated with osteoporosis

-

25-Hydroxyvitamin D level: Vitamin D insufficiency can predispose to osteoporosis

-

Serum protein electrophoresis: Multiple myeloma may be associated with osteoporosis

-

24-hour urine calcium/creatinine: Hypercalciuria may be associated with osteoporosis; further investigation with measurement of intact parathyroid hormone and urine pH may be indicated; hypocalciuria may indicate malabsorption, which should be further evaluated with a serum vitamin D measurement and consideration of testing for malabsorption syndromes such as celiac sprue

-

Testosterone (total and/or free) and luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone: Male hypogonadism is associated with osteoporosis

Bone mineral density (BMD) measurement is recommended in the following patients [4] :

-

Women age 65 years and older and men age 70 years and older, regardless of clinical risk factors

-

Postmenopausal women and men above age 50–69, younger postmenopausal women and women in menopausal transition based on risk factor profile

-

Postmenopausal women and men age 50 and older who have had an adult-age fracture, to diagnose and determine the degree of osteoporosis

-

Adults with a condition (eg, rheumatoid arthritis) or taking medication (eg, glucocorticoids in a daily dose ≥5 mg prednisone or equivalent for ≥3 months) associated with low bone mass or bone loss

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is currently the criterion standard for the evaluation of BMD. [5, 6] Peripheral DXA is used to measure BMD at the wrist; it may be most useful in identifying patients at very low fracture risk who require no further workup.

DXA provides the patient’s T-score, which is the BMD value compared with that of control subjects who are at their peak BMD. [7, 8, 9] World Health Organization (WHO) criteria define a normal T-score value as within 1 standard deviation (SD) of the mean BMD value in a healthy young adult. Values lying farther from the mean are stratified as follows [8] :

-

T-score of –1 to –2.5 SD indicates osteopenia

-

T-score of less than –2.5 SD indicates osteoporosis

-

T-score of less than –2.5 SD with fragility fracture(s) indicates severe osteoporosis

DXA also provides the patient’s Z-score, which reflects a value compared with that of persons matched for age and sex. Z-scores adjusted for ethnicity or race should be used in the following patients:

-

Premenopausal women

-

Men younger than 50 years

-

Children

Z-score values of –2.0 SD or lower are defined as "below the expected range for age" and those above –2.0 SD as "within the expected range for age." The diagnosis of osteoporosis in these groups should not be based on densitometric criteria alone.

The BHOF recommends considering imaging to detect subclinical vertebral fractures for the following patients [10] :

-

All women aged ≥ 65 years and all men aged ≥ 80 years whose T-score at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck is −1.0 or less

-

Men aged 70-79 years whose T-score at the lumbar spine, total hip, or femoral neck is −1.5 or less

In addition, BHOF guidelines recommend vertebral imaging in postmenopausal women and men age ≥ 50 years with any of the following specific risk factors:

-

Fracture during adulthood (age ≥ 50 years)

-

Height loss of 1.5 in or more from peak height during young adulthood, or of 0.8 in or more from last documented height measurement

-

Recent or ongoing long-term glucocorticoid treatment

-

Medical conditions associated with bone loss (eg, hyperparathyroidism)

If bone density testing is not available, vertebral imaging may be considered based on age alone.

Other plain radiography features and recommendations are as follows:

-

Obtain radiographs of the affected area in symptomatic patients.

-

Lateral spine radiography can be performed in asymptomatic patients in whom a vertebral fracture is suspected; a scoliosis series is useful for detecting occult vertebral fractures.

-

Radiographic findings can suggest the presence of osteopenia or bone loss but cannot be used to diagnose osteoporosis.

-

Radiographs may also show other conditions, such as osteoarthritis, disk disease, or spondylolisthesis.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Lifestyle modification for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures includes the following [11] :

-

Increasing weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercise to improve agility, strength, posture, and balance, which may reduce the risk of falls

-

Ensuring optimum calcium and vitamin D intake as an adjunct to active anti-fracture therapy and balanced diet

-

Tobacco cessation

-

Limiting alcohol consumption

-

Removing potential risk factors to avoid falls

Pharmacologic therapy

The NOF recommends reserving pharmacologic therapy for postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older who present with the following [4] :

-

Fragility fracture: a hip or vertebral fracture (vertebral fractures may be clinical or morphometric (ie, identified on a radiograph alone)

-

T-score of –2.5 or less at the femoral neck, total hip, spine, or 33% of radius after appropriate evaluation to exclude secondary causes

-

Low bone mass (T-score of –1.0 to –2.5 at the femoral neck or spine) and a 10-year probability of a hip fracture of 3% or greater or a 10-year probability of a major osteoporosis-related fracture of 20% or greater, based on the US-adapted fracture risk assessment tool ( FRAX)

Guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology include the following recommendations for choosing drugs to treat postmenopausal osteoporosis [11] :

-

First-line agents for most high fracture risk patients: alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, ibandronate, raloxifene (latter two not recommended for the reduction of nonvertebral or hip fracture risk)

-

First-line agents for spine-specific indications in select patients: ibandronate and raloxifene

-

First-line agents for high fracture risk patients unable to use oral therapy: zoledronic acid, denosumab

-

First-line agents for very high fracture risk, including those with multiple fractures: teriparatide, abaloparatide for up to two years, romosozumab for up to one year (should not be considered in women at high risk of cardiovascular disease or stroke)

-

Sequential agents: anabolic agents (eg, teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab) should be followed with a bisphosphonate or denosumab

Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology for the treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis include the following [12] :

-

Designation of moderate-to-high risk or low-risk categories for adults ≥40 years of age receiving long-term glucocorticoids by fracture risk score (using the FRAX score)

-

No tools to estimate absolute fracture risk in children or adults ≤40 years of age. Considered high risk if previously sustained osteoporotic fracture and moderate risk if on glucocorticoid treatment ≥7.5 mg for 6 months and had either hip or spine BMD Z-score less than -3 or 2 or rapidly declining hip or spine BMD ≥ 10% in one year while on glucocorticoid treatment

-

Strong or conditional recommendations for initiation of treatment in women with non-childbearing potential and men on glucocorticoids with high, moderate, to low fracture risk in order of preference: oral bisphosphonates, IV bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab, and raloxifene

Medical care also includes identifying and treating potentially treatable underlying causes of osteoporosis, such as hyperparathyroidism and hyperthyroidism.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Osteoporosis is a chronic, progressive disease of multifactorial etiology (see Etiology) and is the most common metabolic bone disease in the United States. It has been most frequently recognized in postmenopausal women, persons with small bone structure, the elderly, and in whites and Asians, although it does occur in both sexes, all races, and all age groups. Screening of at-risk populations is essential and can identify persons with osteoporosis before fractures occur (see Workup).

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility. [13] The disease often does not become clinically apparent until a fracture occurs.

Osteoporosis represents an increasingly serious health and economic problem in the United States and around the world. [14] Many individuals, male and female, experience pain, disability, and diminished quality of life as a result of having this condition. Over recent decades, osteoporosis has gone from being viewed as an inevitable consequence of aging to being recognized as a serious, eminently preventable and treatable disease.

Despite the adverse effects of osteoporosis, it is a condition that is often overlooked and undertreated, in large part because it is so often clinically silent before manifesting in the form of fracture. Fractures in patients with osteoporosis can occur after minimal or no trauma. [4] For example, a Gallup survey performed by the National Osteoporosis Foundation in 2000 revealed that 86% of women with osteoporosis had never discussed its prevention with their physicians. [15] Failure to identify at-risk patients, to educate them, and to implement preventive measures may lead to tragic consequences.

Medical care includes lifestyle modifications including exercise, smoking cessation, and avoiding excess alcohol intake along with taking calcium, vitamin D, and antiresorptive agents such as bisphosphonates, the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene,, and denosumab. Anabolic agents, include: teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab (see Medication), are available as well. [16] Prevention and recognition of the secondary causes of osteoporosis are first-line measures to lessen the impact of this condition.

WHO definition of osteoporosis

Bone mineral density (BMD) scores are related to peak bone mass and, subsequently, bone loss. Whereas the T-score is the patient’s bone density compared with the BMD of control subjects who are at their peak BMD, the Z-score reflects a bone density compared with that of patients matched for age and sex. [7, 8, 9]

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) definitions of osteoporosis, which are based on BMD measurements in white women, are summarized in Table 1, below. [8, 9] For each standard deviation (SD) reduction in BMD, the relative fracture risk is increased 1.5-3 times. The WHO definition applies to postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older. Although these definitions are necessary to establish the prevalence of osteoporosis, they should not be used as the sole determinant of treatment decisions. This diagnostic classification should not be applied to premenopausal women, men younger than 50 years, or children.

Table 1. WHO Definition of Osteoporosis Based on BMD Measurements by DXA (Open Table in a new window)

Definition |

Bone Mineral Density Measurement |

T-Score |

Normal |

BMD within 1 SD of the mean bone density for young adult women |

T-score ≥ –1 |

Low bone mass (osteopenia) |

BMD 1–2.5 SD below the mean for young adult women |

T-score between –1 and –2.5 |

Osteoporosis |

BMD ≥2.5 SD below the normal mean for young-adult women |

T-score ≤ –2.5 |

Severe or “established” osteoporosis |

BMD ≥2.5 SD below the normal mean for young-adult women in a patient who has already experienced ≥1 fracture |

T-score ≤ –2.5 (with fragility fracture[s]) |

Sources: (1) World Health Organization (WHO). WHO scientific group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level: summary meeting report. Available at: https://www.who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2020 [17] (2) Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. Nov 1994;4(6):368-81. [9] (3) Czerwinski E, Badurski JE, Marcinowska-Suchowierska E, Osieleniec J. Current understanding of osteoporosis according to the position of the World Health Organization (WHO) and International Osteoporosis Foundation. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. Jul-Aug 2007;9(4):337-56. [8] BMD = bone mineral density; DXA = dual x-ray absorptiometry; SD = standard deviation; T-score = a measurement expressed in SD units from a given mean that is equal to a patient's BMD measured by DXA minus the value in a young healthy person, divided by the SD measurement in the population. |

||

The WHO recommends incorporating clinical risk factors into decision making about osteoporosis, rather than relying solely on the use of bone mineral measurements. BMD has high specificity but low sensitivity, meaning that the risk of a fracture is high when the BMD indicates that osteoporosis is present, but is by no means negligible when BMD is normal. [17]

Z-scores should be used in premenopausal women, men younger than 50 years, and children. Z-scores adjusted for ethnicity or race should be used, with Z-scores of –2.0 or lower defined as "below the expected range for age" and with Z-scores above –2.0 being defined as "within the expected range for age." Again, the diagnosis of osteoporosis in these groups should not be based on densitometric criteria alone.

For more information, see the following:

Pathophysiology

It is increasingly being recognized that multiple pathogenetic mechanisms interact in the development of the osteoporotic state. Understanding the pathogenesis of osteoporosis starts with knowing how bone formation and remodeling occur.

Normal bone formation and remodeling

Bone undergoes both radial and longitudinal growth and is continually remodeled throughout our lives in response to microtrauma. [18] Bone remodeling renews bone strength and mineral, preventing the accumulation of damaged bone. [18] Bone remodeling occurs at discrete sites within the skeleton and proceeds in an orderly fashion, and bone resorption is always followed by bone formation, a phenomenon referred to as coupling.

Dense cortical bone and spongy trabecular or cancellous bone differ in their architecture but are similar in molecular composition. Both types of bone have an extracellular matrix with mineralized and nonmineralized components. The composition and architecture of the extracellular matrix are what imparts mechanical properties to bone. Bone strength is determined by collagenous proteins (tensile strength) and mineralized osteoid (compressive strength). [19] The greater the concentration of calcium, the greater the compressive strength. In adults, approximately 25% of trabecular bone is resorbed and replaced each year, compared with only 3% of cortical bone. Up to 10% of the skeleton is being remodelled at any one time.

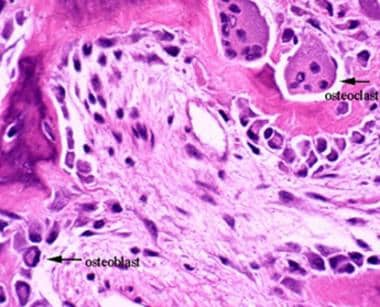

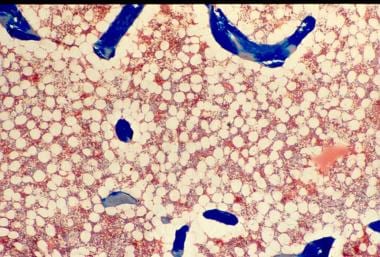

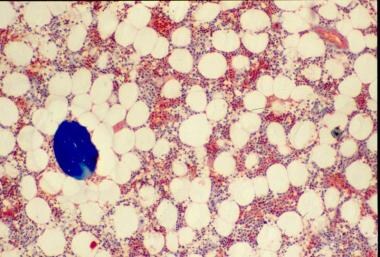

Osteoclasts, derived from hematopoietic precursors, are responsible for bone resorption, whereas osteoblasts, from mesenchymal cells, are responsible for bone formation (see the images below). The 2 types of cells are dependent on each other for production and linked in the process of bone remodeling.

Osteoblasts not only secrete and mineralize osteoid but also appear to control the bone resorption carried out by osteoclasts. Osteocytes, which are terminally differentiated osteoblasts embedded in mineralized bone, direct the timing and location of bone remodeling. In osteoporosis, the coupling mechanism between osteoclasts and osteoblasts is thought to be unable to keep up with the constant microtrauma to trabecular bone. Osteoclasts require weeks to resorb bone, whereas osteoblasts need months to produce new bone and on average bone formation takes 4 to 6 months to be completed. Therefore, any process that increases the rate of bone remodeling results in net bone loss over time. [13]

Bone remodeling has 4 sequential phases: activation precedes resorption, which precedes reversal, which precedes the formation of a new osteon and the process is the same in both cortical spongy trabecular or cancellous bone. [18] 'Activation' is defined as the conversion of bone surface from quiescence to active, which is followed by the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into mature osteoclasts in the ‘resorption’ phase. In the ‘reversal’ phase, osteoclasts complete the resorption process and produce signals that directly or indirectly initiate bone formation, and in the final ‘formation’ phase, mesenchymal cells differentiate into functional osteoblasts to make the bone matrix.

This image depicts bone remodeling with osteoclasts resorbing one side of a bony trabecula and osteoblasts depositing new bone on the other side.

This image depicts bone remodeling with osteoclasts resorbing one side of a bony trabecula and osteoblasts depositing new bone on the other side.

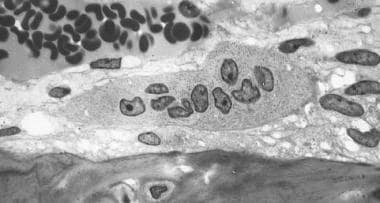

Osteoclast, with bone below it. This image shows typical distinguishing characteristics of an osteoclast: a large cell with multiple nuclei and a "foamy" cytosol.

Osteoclast, with bone below it. This image shows typical distinguishing characteristics of an osteoclast: a large cell with multiple nuclei and a "foamy" cytosol.

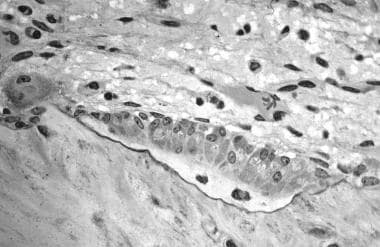

In this image, several osteoblasts display a prominent Golgi apparatus and are actively synthesizing osteoid. Two osteocytes can also be seen.

In this image, several osteoblasts display a prominent Golgi apparatus and are actively synthesizing osteoid. Two osteocytes can also be seen.

Furthermore, in periods of rapid remodeling (eg, after menopause), bone is at an increased risk for fracture because the newly produced bone is less densely mineralized, the resorption sites are temporarily unfilled, and the isomerization and maturation of collagen are impaired. [20]

Activation frequency reflecting the bone remodelling rate increased to double at menopause, triple by 13 years later, and remained at high levels in osteoporotic patients, which contributes to increases in age-related skeletal fragility in women. Bone remodeling increases substantially in the years after menopause and remains increased in older osteoporosis patients.

The receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL)/receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B (RANK)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) system is the final common pathway for bone resorption. Osteoblasts and activated T cells in the bone marrow produce the RANKL cytokine. RANKL binds to RANK expressed by osteoclasts and osteoclast precursors to promote osteoclast differentiation. OPG is a soluble decoy receptor that inhibits RANK-RANKL by binding and sequestering RANKL. [21]

Bone mass peaks around the third decade of life and slowly decrease afterward. A failure to attain optimal bone strength by this point is one factor that contributes to osteoporosis, which explains why some young postmenopausal women have a low bone mineral density (BMD) and why some others have osteoporosis. Therefore, nutrition and physical activity are important during growth and development. Nevertheless, hereditary factors play the principal role in determining an individual's peak bone strength. In fact, genetics account for up to 80% of the variance in peak bone mass between individuals. [13, 22]

Alterations in bone formation and resorption

Osteoporosis is multifactorial with an interplay of genetic, intrinsic, exogenous, and lifestyle factors. [23] The hallmark of osteoporosis is a reduction in skeletal mass caused by an imbalance between bone resorption and bone formation. Under physiologic conditions, bone formation and resorption are in a fair balance. A change in either—that is, increased bone resorption or decreased bone formation—may result in osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis can be caused both by a failure to build bone and reach peak bone mass as a young adult and by bone loss later in life. Accelerated bone loss can be affected by hormonal status, as occurs in perimenopausal women; can impact elderly men and women, and can be secondary to various disease states and medications.

Aging and loss of gonadal function are the two most important factors contributing to the development of osteoporosis. Studies have shown that bone loss in women accelerates rapidly in the first years after menopause. The lack of gonadal hormones is thought to up-regulate osteoclast progenitor cells. Estrogen deficiency leads to increased expression of RANKL by osteoblasts and decreased release of OPG; increased RANKL results in recruitment of higher numbers of preosteoclasts as well as increased activity, vigor, and lifespan of mature osteoclasts.

Estrogen deficiency

Estrogen deficiency not only accelerates bone loss in postmenopausal women but also plays a role in bone loss in men. Estrogen deficiency can lead to excessive bone resorption accompanied by inadequate bone formation. Estrogen deficiency increases the number of osteoclasts and decreases the number of osteoblasts resulting in overall bone resorption. Of note, fracture risk is inversely proportional to the estrogen level in postmenopausal women. [24] Osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts all express estrogen receptors. In addition, estrogen affects bones indirectly through cytokines and local growth factors. The estrogen-replete state may enhance osteoclast apoptosis via increased production of transforming growth factor (TGF)–beta.

Estrogen deficiency increases while estrogen treatment decreases the rate of bone remodeling and the amount of bone loss during the remodeling cycle. In the absence of estrogen, T cells promote osteoclast recruitment, differentiation, and prolonged survival via interleukin-1 ( IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha. A murine study, in which either the mice's ovaries were removed or sham operations were performed, found that IL-6 and granulocyte-macrophage CFU levels were much higher in the ovariectomized mice. [25] This finding provided evidence that estrogen inhibits IL-6 secretion and that IL-6 contributes to the recruitment of osteoclasts from the monocyte cell line, thus contributing to osteoporosis.

IL-1 has also been shown to be involved in the production of osteoclasts. The production of IL-1 is increased in bone marrow mononuclear cells from ovariectomized rats. Administering IL-1 receptor antagonist to these animals prevents the late stages of bone loss induced by the loss of ovarian function, but it does not prevent the early stages of bone loss. The increase in the IL-1 in the bone marrow does not appear to be a triggered event but, rather, a result of removal of the inhibitory effect of sex steroids on IL-6 and other genes directly regulated by sex steroids.

T cells also inhibit osteoblast differentiation and activity and cause premature apoptosis of osteoblasts through cytokines such as IL-7. Finally, estrogen deficiency sensitizes bone to the effects of parathyroid hormone (PTH).

Osteoimmunology

The term osteoimmunology is defined as the interaction between the skeletal system and the immune system. Osteoclastogenic proinflammatory cytokine in particularly TNF, IL-1, 1L-6, or IL-7 is increased in the first ten years in postmenopausal osteoporotic patients. Of note, Crohn's and rheumatoid arthritis are inflammatory conditions that promote osteoporosis. [26]

T cells are considered to play a role and were found to produce more TNF in postmenopausal women with osteoporotic fracture. [26] Recently, a mechanism was promoted whereby the loss of estrogen results in rapid bone loss by activating low-grade inflammation resulting in osteoporosis in the acute phase of bone catabolic activity in ovariectomized mice. [26] It was found that ovariectomy in mice results in increased dendritic cells which express IL-7 and IL-15 inducing antigen-independent production of IL-17A and TNFα in a subset of memory T cells. The study found that ovariectomized mice with T- cell ablation of IL15RA result in no 1L-17A and TNFα expression and no increase in bone resorption or bone loss. [27]

B lymphocytes play a role in osteoporosis by producing RANKL and OPG which regulates the RANK/ RANKL/OPG axis. Production of RANKL by B-lymphocyte is increased in postmenopausal women. The ablation of RANKL in B cells in mice resulted in partial protection from trabecular bone loss post ovariectomy. [26]

Aging

Postmenopausal bone loss is associated with excessive osteoclast activity. Senile osteoporosis may also be associated with excessive osteoclast activity but there may also be a progressive decline in the supply of osteoblasts in proportion to the demand. This demand is ultimately determined by the frequency with which new multicellular units are created and new cycles of remodeling are initiated.

After the third decade of life, bone resorption exceeds bone formation and leads to osteopenia and, in severe situations, osteoporosis. Women lose 30-40% of their cortical bone and 50% of their trabecular bone over their lifetime, as opposed to men, who lose 15-20% of their cortical bone and 25-30% of trabecular bone. Aging deteriorates bone structure, composition, and function leading to bone loss being evident before sex steroid deficiency. Aging results in a combination of cortical thinning, increased cortical porosity, thinning of the trabeculae, and loss of trabecular connectivity. [28]

Calcium deficiency

Calcium, vitamin D, and PTH help maintain bone homeostasis. Insufficient dietary calcium or impaired intestinal absorption of calcium due to aging or disease can lead to secondary hyperparathyroidism. PTH is secreted in response to low serum calcium levels. It increases calcium resorption from bone, decreases renal calcium excretion, and increases renal production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25[OH]2 D)—an active hormonal form of vitamin D that optimizes calcium and phosphorus absorption, inhibits PTH synthesis, and plays a minor role in bone resorption.

Vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent in the older population and can result in secondary hyperparathyroidism via decreased intestinal calcium absorption.

Osteoporotic fractures

Osteoporotic fractures represent the clinical significance of these derangements in the bone. They can result both from low-energy trauma, such as falls from a sitting or standing position, and from high-energy trauma, such as a pedestrian struck in a motor vehicle accident. Fragility fractures, which occur secondary to low-energy trauma, are characteristic of osteoporosis. The most common osteoporotic fracture includes femoral neck, pathologic fractures of the vertebrae, lumbar and thoracic vertebral fractures, and distal radius fractures. The least common osteoporotic fracture includes open fractures of the proximal humerus and closed fractures of the skull and facial bones. [29]

Nearly all osteoporotic hip fractures are related to falls. [30] The frequency and direction of falls can influence the likelihood and severity of fractures. The risk of falling may be amplified by neuromuscular impairment due to vitamin D deficiency with secondary hyperparathyroidism or to corticosteroid therapy.

Vertebral bodies are composed primarily of cancellous bone with interconnected horizontal and vertical trabeculae. Osteoporosis not only reduces bone mass in vertebrae but also decreases interconnectivity in their internal scaffolding. [19] Therefore, minor loads can lead to vertebral compression fractures.

An understanding of the biomechanics of bone provides greater appreciation as to why bone may be susceptible to an increased risk of fracture. In bones that sustain vertical loads, such as tibial and femoral metaphyses and vertebral bodies, resistance to lateral bowing and fractures is provided by a horizontal trabecular cross-bracing system that helps support the vertical elements. Disruption of such trabecular connections is known to occur preferentially in patients with osteoporosis, particularly in postmenopausal women, making females more at risk than males for vertebral compression fractures (see the images below).

Osteoporosis is defined as a loss of bone mass below the threshold of fracture. This slide (methylmethacrylate embedded and stained with Masson's trichrome) demonstrates the loss of connected trabecular bone.

Osteoporosis is defined as a loss of bone mass below the threshold of fracture. This slide (methylmethacrylate embedded and stained with Masson's trichrome) demonstrates the loss of connected trabecular bone.

The bone loss of osteoporosis can be severe enough to create separate bone "buttons" with no connection to the surrounding bone. This easily leads to insufficiency fractures.

The bone loss of osteoporosis can be severe enough to create separate bone "buttons" with no connection to the surrounding bone. This easily leads to insufficiency fractures.

Rosen and Tenenhouse studied the unsupported trabeculae and their susceptibility to fracture within each vertebral body and found an extraordinarily high prevalence of trabecular fracture callus sites within vertebral bodies examined at autopsy—typically, 200-450 healing or healed fractures per vertebral body. [31] These horizontal trabecular fractures are asymptomatic, and their accumulation reflects the impact of lost trabecular bone and greatly weakens the cancellous structure of the vertebral body.

The reason for preferential osteoclastic severance of horizontal trabeculae is unknown. Some authors have attributed this phenomenon to overaggressive osteoclastic resorption.

Osteoporosis versus osteomalacia

Osteoporosis may be confused with osteomalacia. The normal human skeleton is composed of a mineral component, calcium hydroxyapatite (60%), and organic material, mainly collagen (40%). In osteoporosis, the bones are porous and brittle, whereas, in osteomalacia, the bones are soft. This difference in bone consistency is related to the mineral-to-organic material ratio. In osteoporosis, the mineral-to-collagen ratio is within the reference range, whereas in osteomalacia, the proportion of mineral composition is reduced relative to organic material content.

The Wnt signaling pathway and bone

The Wnt family is a highly conserved group of proteins that were initially studied in relationship with cancer initiation and progression due to their involvement in intercellular communication. [32] Subsequently, the Wnt signaling cascade was recognized as a critical regulator of bone metabolism.

Wnt signaling plays a key role in the fate of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are the progenitor cells of mature bone-forming osteoblasts. [33] MSCs have the capability to differentiate into adipocytes, chondrocytes, neurons, and muscle cells, as well as into osteoblasts. [34] Certain Wnt signaling pathways promote the differentiation of MSCs along the osteoblast lineage. The emerging details about the specific molecules involved in the Wnt pathway have improved the understanding of bone metabolism and led to the development of new therapeutic targets for metabolic bone diseases.

Wnt signal activation may progress along one of three pathways, with the “canonical” pathway involving β-catenin being most relevant to bone metabolism. The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is initiated by the binding of a Wnt protein to an extracellular co-receptor complex consisting of “Frizzled” (Fr) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein–5 or –6 (LRP5, LRP6). [35] This activation recruits another protein, “Disheveled” (Dvl) to the intracellular segment of the Fz/Dvl co-receptor. [36] This is where β-catenin comes into play.

β-Catenin is an important intracellular signaling molecule and normally exists in a phosphorylated state targeted for ubiquination and subsequent degradation within intracellular lysosomes. Activation of the Wnt pathway leads to dephosphorylation and stabilization of intracellular β-catenin and rising cytosolic concentrations of β-catenin. As the concentration of β-catenin reaches a critical level, β-catenin travels to the nucleus, where it activates the transcription of Wnt target genes. Ultimately, canonical Wnt signaling inhibits the expression of transcription factors important in the differentiation of MSCs such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) and promotes survival of osteoblast lineage cells. [37]

Several human bone abnormalities have been linked to the Wnt pathway. For example, a single amino acid substitution in the LRP5 receptor gene has been associated with high bone mass phenotypes in humans; specifically, the mutant LRP5 receptor had an impaired interaction with the Wnt signal inhibitor Dickkopf-1 (Dkk-1). [38] Similarly, other missense mutations of LRP5 have been implicated in other high bone mass diseases such as Van Buchem disease and osteopetrosis. [39] Conversely, loss-of-function mutations of LRP5 have resulted in a rare but severe congenital osteoporosis in humans. [40]

There are also several antagonists to the Wnt pathway. Two of the most well-known are Dkk-1 and sclerostin. Dkk-1 is secreted by MSCs [41] and binds to LRP-5 and LRP-6, [42] thereby competitively inhibiting Wnt signaling. Interestingly, serum levels of Dkk-1 positively correlate with the extent of lytic bone lesions in patients with multiple myeloma. [43] In animal models, anti-Dkk1 monoclonal antibody accelerates bone formation and increases bone mineral density, and anti-Dkk antibody is under development as a bone-anabolic agent. [44]

Similarly, sclerostin, a product of osteocytes, [45] has also been found to antagonize the Wnt signaling pathway by binding to LRP5 and LRP6. [46] Romosozumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds with and inhibits sclerostin, and thus both increases bone formation and decreases bone resorption, has been approved for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women who are at high risk for fracture. [47]

Additional factors and conditions

Endocrinologic conditions or medications that lead to bone loss (eg, glucocorticoids) can cause osteoporosis. Corticosteroids inhibit osteoblast function and enhance osteoblast apoptosis. [48] High-dose statin therapy has been linked to increased risk for osteoporosis. [49] Polymorphisms of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-alpha, as well as their receptors, have been found to influence bone mass.

Other factors implicated in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis include the following [13] :

-

Polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor

-

Alterations in insulin-like growth factor-1, bone morphogenic protein, prostaglandin E 2, nitrous oxide, and leukotrienes

-

Collagen abnormalities

-

Leptin-related adrenergic signaling

Epigenetics

Prenatal and postnatal factors contribute to adult bone mass. In one study, the health of the mother in pregnancy, the infant’s birth weight, and the child’s weight at age 1 year were predictive of adult bone mass in the seventh decade for men and women. [50] It is postulated that growth in the first year of life programs growth hormone secretion, and that this programming is maintained into the seventh decade. [51] Higher birth weight and rapid growth in the first year of life predicted increased bone mass in adults aged 65-75 years. Maternal nutritional imbalance and deficiency may have an effect that is transmitted to the next generation. [52]

Etiology

Etiologically, osteoporosis is categorized as primary or secondary.

Primary osteoporosis

Primary osteoporosis is the most common form of osteoporosis. It is divided into juvenile and idiopathic osteoporosis; idiopathic osteoporosis can be further subdivided into postmenopausal (type I) and age-associated or senile (type II) osteoporosis. Postmenopausal osteoporosis is primarily due to estrogen deficiency. Senile osteoporosis is primarily due to an aging skeleton and calcium deficiency. SeeTable 2, below.

Table 2. Types of Primary Osteoporosis (Open Table in a new window)

Type of Primary Osteoporosis |

Characteristics |

Juvenile osteoporosis |

|

Idiopathic osteoporosis |

|

|

|

|

|

Secondary osteoporosis

Secondary osteoporosis occurs when an underlying disease, deficiency, or drug causes osteoporosis (see Table 3, below). [53] Up to one-third of postmenopausal women, as well as many men and premenopausal women, have a coexisting cause of bone loss, [11, 54] of which renal hypercalciuria is one of the most important secondary causes of osteoporosis and treatable with thiazide diuretics. [55]

Table 3. Causes of Secondary Osteoporosis in Adults (Open Table in a new window)

Cause |

Examples |

Genetic/congenital |

|

Hypogonadal states |

|

Endocrine disorders [56] |

|

Deficiency states and malabsorption syndromes |

|

Inflammatory diseases |

|

Hematologic and neoplastic disorders |

|

Medications |

|

Miscellaneous |

|

Sources: (1) American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2020 update. Endocr Pract. May2020; 26(Suppl 1):1-46. [11] (2) Kelman A, Lane NE. The management of secondary osteoporosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. Dec 2005;19(6):1021-37. [54] |

|

Risk factors

Risk factors for osteoporosis, such as advanced age and reduced bone mineral density (BMD), have been established by virtue of their direct and strong relationship to the incidence of fractures; however, many other factors have been considered risk factors based on their relationship to BMD as a surrogate indicator of osteoporosis.

Risk factors for osteoporosis include the following [62, 63, 64] :

-

Advanced age (≥50 years)

-

Female sex

-

White or Asian ethnicity

-

Genetic factors, such as a family history of osteoporosis

-

Thin build or small stature (eg, bodyweight less than 127 lb [57.6 kg])

-

Amenorrhea

-

Late menarche

-

Early menopause

-

Postmenopausal state

-

Physical inactivity or immobilization [65]

-

Use of certain drugs (eg, anticonvulsants, systemic steroids, thyroid supplements, heparin, chemotherapeutic agents, insulin)

-

Alcohol and tobacco use

-

Androgen [66] or estrogen deficiency

-

Calcium or vitamin D deficiency

-

Dowager hump

A potentially useful mnemonic for osteoporotic risk factors is OSTEOPOROSIS, as follows:

-

L Ow calcium intake

-

Seizure meds (anticonvulsants)

-

Thin build

-

Ethanol intake

-

Hyp Ogonadism

-

Previous fracture

-

Thyr Oid excess

-

Race (white, Asian)

-

Other relatives with osteoporosis

-

Steroids

-

Inactivity

-

Smoking

Exposure to the antibacterial agent triclosan may increase the risk for osteoporosis in women. Analysis of data on 1848 women from the 2005-2010 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that women in the highest tertile of urinary triclosan level had lower BMD in the total femur, intertrochanter, and lumbar spine; compared with women in the lowest tertile, those in the highest tertile were more likely to have increased prevalence of intertrochanter osteoporosis (odds ratio (OR)=2.464, 95% CI = 1.190, 5.105). [67]

In animal studies, triclosan has been found to disrupt hormone activity, and in vitro studies have shown that it can cause interstitial collagen accumulation and an increase in trabecular bone. The US Food & Drug Administration has banned triclosan from consumer hand sanitizers and other antiseptics, but it continues to be used in a variety of consumer products—including clothing, kitchenware, furniture, and toys—to prevent bacterial contamination. [67]

Epidemiology

According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), in the United States in 2010 more than 10 million adults age 50 years and older had osteoporosis and more than 43 million had low bone mineral density (BMD). In the United States in 2015, as many as 2 million Medicare beneficiaries sustained 2.3 million osteoporotic fractures. Within 12 months of experiencing a new osteoporotic fracture, approximately 15% of patients suffered one or more subsequent fractures and nearly 20% died. Mortality was highest in those with hip fracture, with 30% dying within 12 months. [68] The NOF reported in 2018 that approximately 10.2 million adults in the United States have osteoporosis, with an additional 43.4 million having low bone mass.

Most studies assessing the prevalence and incidence of osteoporosis use the rate of fracture as a marker for the presence of this disorder, although BMD also relates to risk of disease and fracture. The risk of new vertebral fractures increases by a factor of 2-2.4 for each standard deviation (SD) decrease of BMD measurement. Women and men with metabolic disorders associated with secondary osteoporosis have a 2- to 3-fold higher risk of hip and vertebral fractures.

Globally, osteoporosis is by far the most common metabolic bone disease, estimated to affect over 200 million people worldwide. [69] An estimated 75 million people in Europe, the United States, and Japan have osteoporosis. [70]

Age- and sex-related demographics

The risk for osteoporosis increases with age as BMD declines. Senile osteoporosis is most common in persons aged 70 years or older. Secondary osteoporosis, however, can occur in persons of any age. Although bone loss in women begins slowly, it speeds up around the time of menopause, typically at about age 50 years or later. The frequency of postmenopausal osteoporosis is highest in women aged 50-70 years.

The number of osteoporotic fractures increases with age. Wrist fractures typically occur first, when individuals are aged approximately 50-59 years.

Vertebral fractures occur more often in the seventh decade of life. Jensen et al studied Danish women aged 70 years and found a 21% prevalence of vertebral fractures. [71] Melton et al reported that 27% of women in their study had evidence of vertebral fractures by age 65 years. [72]

Ninety percent of hip fractures occur in persons aged 50 years or older, occurring most often in the eighth decade of life. [73]

Women are at a significantly higher risk for osteoporosis. Half of all postmenopausal women will have an osteoporosis-related fracture during their lifetime; 25% of these women will develop a vertebral deformity, and 15% will experience a hip fracture. [74] Risk factors for hip fracture are similar in different ethnic groups. [75]

Men have a higher prevalence of secondary osteoporosis, with an estimated 45-60% of cases being a consequence of hypogonadism, alcoholism, or glucocorticoid excess. [59] Only 35-40% of osteoporosis diagnosed in men is considered primary in nature. Overall, osteoporosis has a female-to-male ratio of 4:1.

Although loss of BMD is typically associated with postmenopausal women, a study to assess the likelihood of low BMD and related risk factors for osteoporosis in men and women aged 35 to 50 years found higher rates of osteopenia in men: 28% of men and 26% of women had osteopenia at the femoral neck region, and 6% and 2%, respectively, had osteoporosis of the lumbar spine. Of the 173 study subjects, 92 (53%) were women and 162 (94%) were white; none had previous known health issues or were taking medications that can affect BMD. [76]

Fifty percent of all women and 21% of all men older than 50 years experience one or more osteoporosis-related fractures in their lifetime. [77] Eighty percent of hip fractures occur in women. [73] Women have a two-fold increase in the number of fractures resulting from nontraumatic causes, as compared with men of the same age.

Racial demographics

Osteoporosis can occur in persons of all races and ethnicities. In general, however, whites (especially of northern European descent) and Asians are at increased risk. In particular, non-Hispanic white women and Asian women are at higher risk for osteoporosis. In the most recent government census, 178 million Chinese were over age 60 years in 2009, a number that the United Nations estimates may reach 437 million—one-third of the population—by 2050. [78]

These numbers suggest that approximately 50% of all hip fractures will occur in Asia in the next century. In fact, although age-standardized incidence rates of fragility fractures, particularly of the hip and forearm, have been noted to be decreasing in many countries over the last decade, that is not the case in Asia. [79]

Table 4, below, summarizes some osteoporosis prevalence statistics among racial/ethnic groups. Note that this disease is under-recognized and undertreated in white and black women. Relative to other racial/ethnic groups, the risk of developing osteoporosis is increasing fastest among Hispanic women.

Table 4. Prevalence of Osteoporosis Among Racial and Ethnic Groups (Open Table in a new window)

Race/Ethnicity |

Sex (age ≥50 y) |

% Estimated to have osteoporosis |

% Estimated to have low bone mass |

Non-Hispanic white; Asian |

Women |

15.8 |

52.6 |

Men |

3.9 |

36 |

|

Non-Hispanic black |

Women |

7.7 |

36.2 |

Men |

1.3 |

21.3 |

|

Hispanic |

Women |

20.4 |

47.8 |

Men |

5.9 |

38.3 |

|

Source: Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. Nov 2014;29(11):2520-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. |

|||

Melton et al reported that the prevalence of hip fractures is higher in white populations, regardless of geographic location. [80] Another study indicated that, in the United States and South Africa, the incidence of hip fractures was lower in Black persons than in age-matched white persons. Cauley et al found that the absolute fracture incidence across BMD distribution was 30-40% lower in Black women than in white women. This lower fracture risk was independent of BMD and other risk factors. [81]

Prognosis

The prognosis for osteoporosis is good if bone loss is detected in the early phases and proper intervention is undertaken. Patients can increase bone mineral density (BMD) and decrease fracture risk with exercise, a diet rich in calcium, and the appropriate anti-osteoporotic medication. In addition, patients can decrease their risk of falls by participating in a multifaceted approach that includes rehabilitation and environmental modifications. Worsening of medical status can be prevented by providing appropriate pain management and, if indicated, orthotic devices.

Effect of fractures on prognosis

Many individuals experience morbidity associated with pain, disability, and diminished quality of life caused by osteoporosis-related fractures. According to a 2004 Surgeon General's report, osteoporosis and other bone diseases are responsible for about 1.5 million fractures per year. Osteoporosis-related fractures result in annual direct care expenditures of $12.2 billion to $17.9 billion. [82] In 2005, over 2 million osteoporosis-related fractures occurred in the United States. [83] A report in 2019 by the National Osteoporosis Foundation noted that an estimated 2 million Americans on Medicare suffered 2.3 million osteoporosis-related bone fractures in 2015. [68]

Osteoporosis is the leading cause of fractures in the elderly. Women aged 50 years have about a 50% lifetime fracture rate as a result of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is associated with 80% of all fractures in people aged 50 years or older. Approximately 33% of women who live to age 90 years will suffer a hip fracture, which is associated with functional decline, nursing home placement, and death. [84]

Researchers analyzed data from a subgroup of the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, a prospective cohort study that began recruiting in 1986. The study had 1528 participants, all of whom were women, with a mean (SD) age of 84.1 (3.4) years. During follow-up, 125 (8.0%) women experienced a hip fracture and 287 (18.8%) died before experiencing this event. Five-year mortality probability was 24.9% (95% CI, 21.8-28.1) among women with osteoporosis and 19.4% (95% CI, 16.6-22.3) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. In both groups, mortality probability similarly increased with more comorbidities and poorer prognosis. In contrast, 5-year hip fracture probability was 13.0% (95% CI, 10.7-15.5) among women with osteoporosis and 4.0% (95% CI, 2.8-5.6) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. The difference was most pronounced among women with more comorbidities or worse prognosis. For example, among women with 3 or more comorbid conditions, hip fracture probability was 18.1% (95% CI, 12.3-24.9) among women with osteoporosis vs 2.5% (95% CI, 1.3-4.2) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. [84]

If full recovery is not achieved, osteoporotic fractures may lead to chronic pain, disability, and, in some cases, death. This is particularly true of vertebral and hip fractures.

Vertebral fractures

Vertebral compression fractures are the most common osteoporotic fracture in the United States with an estimated 700,000 per year. [85] Vertebral compression fractures (see the images below) are associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates. In addition, the impact of vertebral fractures increases as they increase in number. As posture worsens and kyphosis progresses, patients experience difficulty with balance, back pain, respiratory compromise, and an increased risk of pneumonia. Overall function declines, and patients may lose their ability to live independently.

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph demonstrates multiple osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Kyphoplasty has been performed at one level.

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph demonstrates multiple osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Kyphoplasty has been performed at one level.

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph of the patient seen in the previous image following kyphoplasty performed at 3 additional levels.

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph of the patient seen in the previous image following kyphoplasty performed at 3 additional levels.

In one study, Cooper et al found that vertebral fractures increased the 5-year risk of mortality by 15%. [86] In a subsequent study, Kado et al [87] demonstrated that women with one or more fractures had a 1.23-fold increased age-adjusted mortality rate and that women with 5 or more vertebral fractures had a 2.3-fold increased age-adjusted mortality rate.

Furthermore, the mortality rate correlated with number of vertebral fractures: there were 19 deaths per 1000 woman-years in women with no fracture, versus 44 per 1000 woman-years in women with five or more fractures. Vertebral fractures related to risk of subsequent cancer and pulmonary death and severe kyphosis was further correlated with pulmonary deaths.

Symptoms of vertebral fracture may include back pain, height loss, and disabling kyphosis. Compression deformities can lead to restrictive lung disease, abdominal pain, and early satiety.

Hip fractures

More than 250,000 hip fractures are attributed to osteoporosis each year. Like vertebral fractures, they are associated with significantly increased morbidity and mortality rates in men and women. In the year following hip fracture, excess mortality rates can be as high as 20%. [86, 88] Men have higher mortality rates following hip fracture than do women.

Patients with hip fractures incur decreased independence and a diminished quality of life. Of all patients with hip fracture, approximately 20% require long-term nursing care. [4] Among women who sustain a hip fracture, 50% spend time in a nursing home while recovering. Approximately 50% of previously independent individuals become partially dependent, and one third become completely dependent. [89] Only one-third of patients return to their pre-fracture level of function. [90]

Secondary complications of hip fractures include nosocomial infections and pulmonary thromboembolism.

Additional fractures

Patients who have sustained one osteoporotic fracture are at increased risk for developing additional osteoporotic fractures. [70] For example, the presence of at least one vertebral fracture results in a 5-fold increased risk of developing another vertebral fracture. One in 5 postmenopausal women with a new vertebral fracture incurs another vertebral fracture within one year. [91]

Patients with previous hip fracture have a two-fold [92] to 10-fold increased risk of sustaining a second hip fracture. In addition, patients with ankle, knee, olecranon, and lumbar spine fractures have a 1.5-, 3.5-, 4.1-, and 4.8-fold increased risk of subsequent hip fracture, respectively. Site of prior fracture impacts on future risk of osteoporotic fractures independent of BMD such that in postmenopausal women, prior fractures of the spine, humerus, patella, and pelvis are more predictive of future osteoporotic fractures than fractures at other sites. [93]

Fracture risk tools

The fracture risk algorithm (FRAX) was developed to calculate the 10-year probability of a hip fracture and the 10-year probability of any major osteoporotic fracture (defined as clinical spine, hip, forearm, or humerus fracture) in a given patient. These calculations, which are adapted to different geographical locations, account for femoral neck BMD and other clinical risk factors, as follows [94] :

-

Age

-

Sex

-

Personal history of fracture

-

Low body mass index

-

Use of oral glucocorticoid therapy

-

Secondary osteoporosis (eg, coexistence of rheumatoid arthritis)

-

Parental history of hip fracture

-

Current smoking status

-

Alcohol intake (three or more drinks per day)

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends osteoporosis treatment in patients with low bone mass in whom a US-adapted FRAX 10-year probability of a hip fracture is 3% or more or in whom the risk for a major osteoporosis-related fracture is 20% or more. [4] Note that osteoporosis is, by definition, present in those with a fragility fracture, irrespective of their T-score.

Algorithms such as FRAX are useful in identifying patients with low bone mass (T-scores in the osteopenic range) who are most likely to benefit from treatment. A study by Leslie et al demonstrated the effects of including a patient's 10-year fracture risk along with DXA results in Manitoba, Canada. [95] The authors found an overall reduction in dispensation of osteoporosis medications as more women were reclassified into lower fracture risk categories.

Although type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with a higher BMD, a study by Schwartz et al concluded that for a given T score and age or for a given FRAX score, the risk of fracture is higher in patients with type 2 DM than in those without type 2 DM. The study conclusions were based on data from three prospective observational studies, statistics from self-reported incidence of fractures in 9449 women and 7436 men in the United States. [96]

The FRAX tool has a low sensitivity for predicting fracture risk in perimenopausal and early-menopausal women. In a study by Trémollieres et al, FRAX had 50% sensitivity in the 30% of women in the study who were at the highest risk. [97] FRAX also does not include risk of falls; 90% of hip fractures [98] and the majority of Colles fractures are associated with falls. [99]

The Garvan fracture risk tool is not as widely used as the FRAX but is another validated fracture prediction tool that does account for falls, and maybe a better tool for use in men. [100] However, the Garvan fracture does not include variables like parental history of hip fracture, secondary osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, glucocorticoid use, smoking, or intake of alcohol which are included in the FRAX tool. [101]

Another fracture risk assessment tool is the Qfracture tool history of smoking, alcohol, corticosteroid use, parental history, and secondary causes of osteoporosis but unlike the FRAX tool, it includes history of falls but does not include BMD. [101]

Complications

Vertebral compression fractures often occur with minimal stress, such as coughing, lifting, or bending. The vertebrae of the middle and lower thoracic spine and upper lumbar spine are involved most frequently. In many patients, vertebral fracture can occur slowly and without symptoms. Only one-third of people with radiographic vertebral fractures are diagnosed clinically. [102]

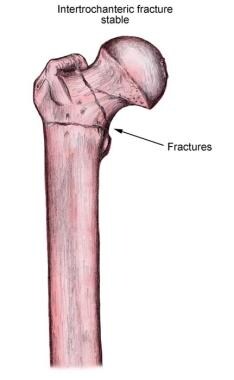

Hip fractures are the most devastating and occur most commonly at the femoral neck and intertrochanteric regions (see the image below). Hip fractures are associated with falls. The likelihood of sustaining a hip fracture during a fall is related to the direction of the fall. Fractures are more likely to occur in falls to the side because less subcutaneous tissue is available to dissipate the impact. Secondary complications of hip fractures include nosocomial infections and pulmonary thromboembolism.

Fractures can cause further complications, including chronic pain from vertebral compression fractures and increased morbidity and mortality secondary to vertebral compression fractures and hip fractures. Patients with multiple fractures have significant pain, which leads to functional decline and a poor quality of life (QOL). [103] They are also at risk for the complications associated with immobility, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pressure ulcers. Respiratory compromise can occur in patients with multiple vertebral fractures that result in severe kyphosis.

Patients with osteoporosis develop spinal deformities and a dowager's hump, and they may lose 1-2 inches of height by their seventh decade of life. These patients can lose their self-esteem and are at increased risk for depression.

Patient Education

Patient education is paramount in the treatment of osteoporosis. Many patients are unaware of the serious consequences of osteoporosis, including increased morbidity and mortality, and only become concerned when osteoporosis manifests in the form of fracture; accordingly, it is important to educate them regarding these consequences. Early prevention and treatment are essential in the appropriate management of osteoporosis.

The focus of patient education is on the prevention of osteoporosis. Prevention has 2 components, behavior modification, and pharmacologic interventions. Appropriate preventive measures may include adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, exercise, cessation of smoking, and moderation of alcohol consumption (see Treatment/Dietary Measures and Treatment/Prevention.)

Patients should be educated about the risk factors for osteoporosis, with a special emphasis on family history and the effects of menopause. Patients also need to be educated about the benefits of calcium and vitamin D supplements, as well as strategies to prevent falls in the elderly (see Primary Care–Relevant Interventions to Prevent Falling in Older Adults: A Systematic Evidence Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF]).

All postmenopausal women older than 65 years should be offered bone densitometry; densitometry should also be offered to younger women and men who are at elevated risk. These patients should understand the benefits of bone density monitoring. Society at large also should be educated about the benefits of exercise with regard to osteoporosis.

For patient education information, see Osteoporosis, Osteoporosis and Calcium, Osteoporosis FAQs, and Osteoporosis in Men.

-

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph demonstrates multiple osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Kyphoplasty has been performed at one level.

-

Osteoporosis. Lateral radiograph of the patient seen in the previous image following kyphoplasty performed at 3 additional levels.

-

Osteoporosis of the spine. Observe the considerable reduction in overall vertebral bone density and note the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

-

Osteoporosis of the spine. Note the lateral wedge fracture in L3 and the central burst fracture in L5. The patient had suffered a recent fall.

-

Normal femoral anatomy.

-

Stable intertrochanteric fracture of the femur.

-

Percutaneous vertebroplasty, transpedicular approach.

-

Asymmetric loss in vertebral body height, without evidence of an acute fracture, can develop in patients with osteoporosis. These patients become progressively kyphotic (as shown) over time, and the characteristic hunched-over posture of severe osteoporosis develops eventually.

-

In kyphoplasty, a KyphX inflatable bone tamp is percutaneously advanced into the collapsed vertebral body (A). It is then inflated, (B) elevating the depressed endplate, creating a central cavity, and compacting the remaining trabeculae to the periphery. Once the balloon tamp is deflated and withdrawn, the cavity (C) is filled under low pressure with a viscous preparation of methylmethacrylate (D).

-

Osteoporosis is defined as a loss of bone mass below the threshold of fracture. This slide (methylmethacrylate embedded and stained with Masson's trichrome) demonstrates the loss of connected trabecular bone.

-

The bone loss of osteoporosis can be severe enough to create separate bone "buttons" with no connection to the surrounding bone. This easily leads to insufficiency fractures.

-

Inactive osteoporosis is the most common form and manifests itself without active osteoid formation.

-

Osteoporosis that is active contains osteoid seams (red here in the Masson's trichrome).

-

Woven bone arising directly from surrounding mesenchymal tissue.

-

This image depicts bone remodeling with osteoclasts resorbing one side of a bony trabecula and osteoblasts depositing new bone on the other side.

-

Osteoclast, with bone below it. This image shows typical distinguishing characteristics of an osteoclast: a large cell with multiple nuclei and a "foamy" cytosol.

-

In this image, several osteoblasts display a prominent Golgi apparatus and are actively synthesizing osteoid. Two osteocytes can also be seen.

-

Severe osteoporosis. This radiograph shows multiple vertebral crush fractures. Source: Government of Western Australia Department of Health.

-

Lateral spine radiograph depicting osteoporotic wedge fractures of L1-L2. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

-

Dual-energy computed tomography (CT) scan in a patient with involutional osteoporosis. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum and the pubic rami are seen on an isotopic bone scan as a characteristic H, or Honda, sign (arrows), which appears as intense radiopharmaceutical uptake at the fracture sites.

-

Schematic example of an early bone densitometer: the QDR-1000 System (spine scan). (From: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Bone Densitometry Manual. Rockville, Md: Westat, Inc; 1989 [revised].)

-

Bone density scanner. This machine measures bone density to check for osteoporosis in the elderly and other vulnerable subjects. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

-

Example of a dual energy x-ray absorption (DXA) scan. This image is of the left hip bone. Source: Government of Western Australia Department of Health.

-

Example of a dual energy x-ray absorption (DXA) scan. This image is of the lumbar spine. Source: Government of Western Australia Department of Health.

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Approach Considerations

- Laboratory Studies

- Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover

- Plain Radiography

- Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA)

- Quantitative Computed Tomography

- Single-Photon Emission CT

- Quantitative Ultrasonography

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- Bone Scanning

- Bone Biopsy and Histologic Features

- Show All

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- Tables

- References