Overview

Disorders impairing a patient’s communication abilities may involve voice, speech, language, hearing, and/or cognition. [1, 2] Recognizing and addressing communication disorders is important; failure to do so may result in isolation, depression, and loss of independence. [3, 4]

A voice disorder exists when the voice’s quality, pitch, or volume differs from that of other persons of similar age, culture, and geographic location. Dysphonia is classified as either an organic or a functional disorder of the larynx. [5, 6]

Another type of communication problem, dysarthria, encompasses a group of motor speech disorders caused by a disturbance in the neuromuscular control of speech. [3] A second form of motor speech disorder, apraxia, occurs in the presence of significant weakness or incoordination of the muscles of speech production.

Aphasia is a language disorder that results from damage to the areas of the brain responsible for language comprehension and expression, [7] while a cognitive-communicative disorder affects the ability to communicate by impairing the pragmatics, or social rules, of language.

The Normal Communication Process

Communication is a multidimensional dynamic process that allows human beings to interact with their environment. Through communication, people are able to express thoughts, needs, and emotions. Communication is an intricate process that involves cerebration, cognition, hearing, speech production, and motor coordination. Evaluation of a communication disorder includes consideration of all aspects of the normal communication process.

Language is the transformation of thoughts into meaningful symbols communicated by speech, writing, or gestures. Thoughts are organized by the brain, specifically the left hemisphere, and encoded into a sequence according to learned grammatic and linguistic rules. These rules govern the way sounds are organized (phonology), the meaning of words (semantics), how words are formed (morphology), how words are combined into phrases (syntax), and the use of language in context (pragmatics).

Speech production

Speech involves the coordinated motor activity of muscles involved in respiration, phonation, resonance, and articulation. The entire system is modulated by central and peripheral innervation, including with cranial nerves V, X, XI, and XII, as well as with the phrenic and intercostal nerves.

Respiratory muscles, specifically the muscles associated with expiration, must generate enough air pressure to provide adequate breath support to make speech audible. The diaphragm is the main muscle of expiration; however, the abdominal and intercostal muscles help to control the force and length of exhalation for speech.

Phonatory muscles of the larynx generate vibratory energy during vocal cord approximation to produce sound. [8] Vocal pitch and intensity are modified by subglottic air pressure, tension of the vocal cords, and position of the larynx. Articulatory muscles within the pharynx, mouth, and nose form the tone of the sound. The coordinated action of these muscles produces speech. By altering the shape of the vocal tract, we are capable of producing a tremendous range of sounds.

Sound waves are transformed by the auditory system into neural input for the speaker and the listener. The outer ear detects sound-pressure waves in the air and converts them into mechanical vibrations in the middle and inner ear. The cochlea then transforms these mechanical vibrations into vibrations in fluid, which act on the nerve endings of the eighth cranial nerve. Thus, the process of communication begins and ends in the brain.

Voice Disorders (Dysphonia)

Voice is the audible sound produced by passage of air through the larynx. Voice typically is defined by the elements of pitch (frequency), loudness (intensity), and quality (complexity). By varying the pitch, loudness, rate, and rhythm of voice (prosody), the speaker can convey additional meaning and emotion to words.

A voice disorder exists when the quality, pitch, or volume differs from that of other persons of similar age, culture, and geographic location. Dysphonia is classified as either an organic or a functional disorder of the larynx. [5, 6, 9]

Organic dysphonia

Organic disorders cause an interruption in the smooth approximation of the vocal folds. [8] Such disorders include the following:

-

Vocal nodules - Callus formation on the vocal fold

-

Laryngitis - Inflammation

-

Vocal polyps - Fluid-filled sacs on the vocal fold

-

Laryngeal and esophageal tumors

-

Contact ulcers

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

Surgery - Eg, laryngectomy or tracheostomy

Functional dysphonia

Functional disorders affect the quality and volume of the voice. They include the following:

-

Vocal abuse/misuse - Including screaming, excessive throat clearing, and substance abuse (eg, smoking, alcohol)

-

Normal aging [12]

-

Psychosocial disorders

-

Hysterical conditions

-

Conversion voice impairment

A study of 162 teachers with behavioral dysphonia suggested that a 6-week course of vocal function exercises can prevent one out of three cases of dysphonia aggravation, as compared with prevention of one out of five cases using a voice amplifier. [13]

Diagnosis and referral

Rule out a treatable medical condition in all patients with voice disorders. For example, a voice disorder may be one of the first symptoms of laryngeal cancer. Patients should be referred to an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat [ENT] specialist) for specialized examinations, which may include peripheral oral/nasal examination, voice analysis, and indirect or fiberoptic laryngoscopy.

Once an organic disorder has been either treated or excluded, the patient may be referred to a speech-language pathologist (SLP). The SLP helps the patient to produce the most functional voice possible. [14, 15]

In a retrospective study of more than 60,000 patients over age 65 years with a laryngeal/voice disorder, Roy et al found that age, gender, comorbidities, geographic location, and physician type (primary care physician [PCP] or otolaryngologist) were associated with the specific disorder diagnosed. For example, PCPs arrived at a diagnosis of acute laryngitis more often than otolaryngologists did, while otolaryngologists more often diagnosed patients as having nonspecific dysphonia and laryngeal changes/lesions. [16]

Laryngectomy rehabilitation

Laryngectomy remains a common procedure for the treatment of laryngeal cancer. Total laryngectomy results in the complete loss of voice (aphonia). Options for the restoration of speech following laryngectomy are detailed below. [17]

External prosthetic devices for speech restoration include the following:

-

Electrolarynx - This device may be placed either into the oral cavity or through the neck tissue to introduce a vibratory tone into the mouth and pharynx; the muscles of articulation then produce words from this tone [18]

-

Pneumatic reed - This device is placed over a tracheostoma; air passes across the reed, producing a tone that is carried into the mouth.

-

Tracheo-esophageal shunt - This 1-way–valve voice prosthesis shunts air from the lungs into the esophagus; the air is vibrated in the pharyngo-esophageal segment to produce an esophageal voice.

Esophageal speech is accomplished by training the patient to suck air into the esophagus, hold the air, and then release it in a controlled manner through the oral cavity.

Motor Speech Disorders

The production of speech depends on motor coordination of the structures of the respiratory system, larynx, pharynx, and oral cavity. Disorders of motor speech are classified into dysarthrias and apraxias. [19, 20, 21]

Dysarthria

The term dysarthria encompasses a group of motor speech disorders caused by a disturbance in the neuromuscular control of speech. [3] These disorders result from central or peripheral nervous system damage and are manifested as weakness, slowness, or incoordination of speech. Any or all of the normal motor structures may be involved.

Unless a concomitant language disorder exists, a person with dysarthria has intact comprehension and is able to understand written, spoken, and read language. The most typical dysarthrias are summarized in Table 1, below.

Table 1. Summary of Dysarthrias (Open Table in a new window)

Type |

Characteristics |

Neurologic Location |

Neuromuscular Deficit |

Examples |

Flaccid |

Hypernasal, breathy voice quality; imprecise articulation |

Lower motor neuron |

Weakness, hypotonia, fasciculations |

Bulbar palsy, poliomyelitis, myasthenia gravis |

Spastic |

Strained/harsh voice quality, hypernasal, slow rate, monopitch |

Upper motor neuron |

Hypertonia, weakness, reduced range and speed of movement |

Pseudobulbar palsy, stroke, encephalitis, spastic cerebral palsy |

Ataxic |

Excess and equal stress, slow rate |

Cerebellum |

Hypotonia, slow and inaccurate movement |

Stroke, tumor, alcohol abuse, infection |

Hypokinetic |

Monopitch, reduced loudness, inappropriate silences |

Extrapyramidal |

Rigidity, reduced range and speed of movement |

Parkinson disease, drug induced |

Hyperkinetic |

|

|

|

|

Quick |

Sudden variations in loudness, harsh quality, hypernasal |

Extrapyramidal |

Quick, involuntary, random movements |

Chorea, myoclonus, Tourette syndrome |

Slow |

Unsteady rate and loudness |

Extrapyramidal |

Sustained, distorted, slow movements |

Athetosis, dyskinesia |

Tremors |

Rhythmic alterations in pitch and loudness |

Extrapyramidal |

Involuntary, purposeless movements |

Organic voice tremor |

Mixed |

Hypernasality, harsh voice quality, monopitch, reduced stress, slow rate, variable quality |

Variable, upper and lower motor neurons, cerebellar, extrapyramidal |

Variable weakness, slow movement, limited range of motion, intention tremor, rigidity, spasticity |

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Wilson disease, multiple sclerosis |

The diagnosis of dysarthria is made clinically by assessing the pitch, nasality, articulation, rate, and intelligibility of the patient's speech. Additionally, each of the subsystems of speech (respiratory, laryngeal, pharyngeal, and oral structures) must be assessed. Bedside evaluation of dysarthria includes the following exercises:

-

Alternating motion rates (rapid repetition of "puh, tuh, kuh")

-

Sequential motor rates (rapid repetition of "puh, puh, puh")

-

Prolongation of "aah"

SLPs can administer formal speech intelligibility tests, such as the Tikofsky word list or the Assessment of the Intelligibility of Dysarthric Speech.

The overall goal in the treatment of dysarthria is functional communication in which a patient can reliably communicate his or her basic needs of daily living. A generalized hierarchy of treatment moves through the following 3 stages, based on the severity of speech impairment:

-

Severely involved speakers - Establish a functional means of communication using communication boards or computer-based speech systems

-

Moderately involved speakers - Maximize speech intelligibility with palatal lift or by teaching speakers to control and emphasize words

-

Mildly involved speakers - Increase the naturalness of speech by using a pacing board to control rate or by teaching intonation and appropriate phrasing.

Apraxia

The second category of motor speech disorders, apraxia, involves the capacity to program the positioning of the speech musculature and sequence the movements necessary for speech. [3] Apraxia occurs in the presence of significant weakness or incoordination of the muscles of speech production. The 2 recognized types of apraxia related to speech disorders are oral apraxia and apraxia of speech (AOS).

Oral apraxia is an apraxia of nonverbal oral movements. Patients have difficulty performing movements such as sticking out their tongue, licking their lips, and protruding their lips. Lesions of the premotor cortex are a frequent finding in patients with this disorder. [22]

AOS is a disorder of articulation that encompasses the intonation, rhythm, and stress of speech (prosody). Patients with AOS find it difficult to accurately plan, initiate, and sequence speech movements. Typically, AOS occurs with left frontal lesions adjacent to the Broca area. The following characteristics usually are present:

-

Effortful, groping articulatory movements with attempts at self-correction [23]

-

Dysprosody that is unrelieved by extended periods of normal intonation, rhythm, and stress

-

Articulatory inconsistency or repeated production of the same utterance

-

Difficulty initiating an utterance

Diagnosis is made clinically, based on the above characteristics. Additionally, AOS may be differentiated from dysarthria and aphasia because in AOS, automatic speech, motor control, and other language modalities (ie, listening, reading, writing) are spared. A number of extensive, objective tests exist and may be administered by the SLP to provide additional qualitative and quantitative information.

Treatment of apraxia is designed to teach effective communication strategies and improve volitional control of the oral musculature. Exercises are used to teach sound sequencing, program sound patterns, and improve rhythm in speech.

A study by Chenausky et al indicated that the majority of children with AOS have comorbidities. Out of 375 children in the study with AOS, comorbidities were absent in just one patient. Expressive language impairment existed in more than 95% of the children. Intellectual disability, receptive language impairment, and nonspeech apraxia occurred at significantly greater rates in patients with severe AOS; the same was not true, however, for autism spectrum disorder. [24]

Language Disorders (Aphasia)

Aphasia is a language disorder that results from damage to the areas of the brain responsible for language comprehension and expression. [7] These injuries usually occur in the dominant side of the brain, which, for most people, is the left hemisphere. Depending on the site of the lesion, aphasia may involve spoken and written language expression, auditory comprehension, and reading and writing abilities. [3]

Aphasia may be described by a variety of abnormalities in speech production. Table 2, below, summarizes the terminology used to describe expressive disorders of aphasia.

Table 2. Terminology Describing Expressive Disorders of Aphasia (Open Table in a new window)

Term |

Definition |

Adynamia |

Difficulty initiating speech |

Agrammatism |

Absence of grammatical elements (verbs, articles, pronouns, prepositions) |

Anomia |

Difficulty producing nouns |

Circumlocution |

Utterance of associated words related to the word that cannot be retrieved |

Echolalia |

Repetition of an utterance that does not require repetition |

Jargon |

Well-articulated, but mostly incomprehensible, language |

Logorrhea |

Excessively lengthy, often incomprehensible, but well-articulated language |

Neologism |

Substitution of contrived or invented words, well articulated |

Paragrammatism |

Misuse of grammatical elements |

Phonemic paraphasia |

Substitution of one sound for another (for example, "fable" for "table") |

Semantic paraphasia |

Word substitution belonging to the same semantic class (such as "table" for "chair") |

Stereotypes |

Repetition of nonsensical syllables for all communicative attempts ("dee, dee, dee") |

Telegraphic speech |

Utterance of mostly nouns and verbs |

Aphasias are classified in several ways. Traditionally, aphasia syndromes were classified as expressive or receptive. Individuals with expressive, or motor, aphasia have difficulty producing words and are believed to have a lesion in the Broca area in the dominant frontal lobe. Patients with receptive, or sensory, aphasia have difficulty comprehending language and are thought to have a lesion in the Wernicke area of the dominant temporal lobe.

In the 1960s, a popular modification of the classification system was proposed based on the fluency, or rate of speech. Fluent speech is produced at normal to rapid rates and is effortless and well articulated. Nonfluent speech is slow, labored, and poorly articulated. As a rule, lesions anterior to the fissure of Rolando produce nonfluent aphasias; lesions posterior to this fissure produce fluent aphasias.

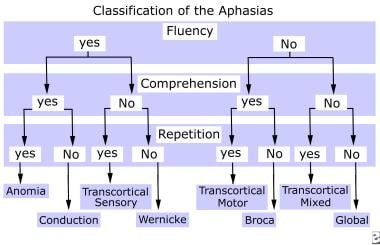

Newer brain imaging techniques, however, have shown that subcortical and right hemispheric structures also contribute to language functions. The traditional classification systems are limited in that they classify the types of disorders according to the site of the lesion only in the dominant cortical hemisphere. The currently accepted classification system evaluates fluency, comprehension, and repetition; it also divides the aphasias into cortical and subcortical forms. Classification of the cortical aphasias is summarized in Table 3 and the diagram below it.

Table 3. Summary of Cortical Aphasias (Open Table in a new window)

Aphasia Type |

Fluency |

Comprehension |

Repetition |

Characteristics |

Lesion Site |

Broca (Motor, expressive) |

Nonfluent |

Good |

Poor |

Effortful, telegraphic, often associated with apraxia, agrammatic |

Left middle cerebral artery (MCA), frontal |

Wernicke (Sensory, receptive) |

Fluent |

Poor |

Poor |

Neologisms, paraphasias, well articulated, paragrammatism |

Left MCA, temporal |

Conduction |

Fluent |

Good |

Poor |

Paraphasias, normal rate |

Arcuate fasciculus, left MCA |

Anomia |

Fluent |

Good |

Good |

Circumlocutions, word-finding difficulty |

Angular gyrus, left MCA |

Transcortical Motor |

Nonfluent |

Good |

Good |

Greater ease of articulation, intact naming, adynamia |

Adjacent to Broca area, left anterior cerebral artery |

Transcortical Sensory |

Fluent |

Poor |

Good |

Neologism, well articulated |

Adjacent to Wernicke area, left posterior cerebral artery |

Mixed Transcortical |

Nonfluent |

Poor |

Good |

Echolalia |

Border zone of frontal, temporal, parietal areas |

Global |

Nonfluent |

Poor |

Poor |

Often associated with apraxia, rare vocalization |

Multiple lobes, left MCA |

Subcortical aphasia

The advent of computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has enhanced our ability to identify small subcortical lesions as causes of aphasia. [25, 26] The following 2 major forms of subcortical aphasias are recognized: (1) thalamic and (2) those due to lesions in the caudate, putamen, and/or internal capsule.

Thalamic aphasia generally consists of fluent speech, mild impairment in comprehension, and intact repetition. Paraphasias, neologism, perseveration, and fluctuating attention are also common in thalamic aphasia.

Lesions involving the putamen and caudate with extension into the internal capsule may cause several aphasic syndromes. The core syndrome is one of relative intact fluency, comprehension, and repetition. Depending on the extent and location of the lesion, the syndrome may include better or worse articulation and comprehension, apraxia, and paraphasias.

Testing

Evaluation of aphasia should be performed by the SLP using a formal, standardized assessment of the components of language. Tests are designed to evaluate the patient's receptive and expressive language capacities by sampling components such as conversational speech, comprehension, repetition, naming, reading, and writing. Several of the most commonly used aphasia batteries are summarized below, in Table 4. [25, 26]

Table 4. Comprehensive Tests for Aphasia (Open Table in a new window)

Test |

Characteristics |

Minnesota Test for Differential Diagnosis of Aphasia (MTDDA) |

Most comprehensive; can identify aphasia type; contains subtests in each major area of language; takes several hours to administer |

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) |

Commonly used; can identify aphasia type; quantitates strengths and weaknesses in various areas of language; takes several hours to administer |

Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) |

Commonly used; based on BDAE but can be completed in 1 hour; classifies aphasia syndromes; assigns a severity of impairment |

Porch Index of Communicative Ability (PICA) |

Measures overall communication ability; takes 1½ hours to complete; uses 10 common objects (eg, pen, comb) to elicit patient responses; may be used to predict and follow recovery |

Communication Effectiveness Index (CETI) |

Assesses communication for basic needs, life skills, and health threats; based on observation by patient's significant other in those skill areas |

Treatment

Successful treatment of aphasia is based on the detailed knowledge of a patient's cognitive and linguistic strengths and weaknesses obtained from the formal testing batteries. Traditional treatment strategies focused on syndrome-specific approaches, in which treatment was based on the diagnosed aphasia syndrome. More current strategies promote getting a message across by any means, that is, through language, gestures, drawing, or any other expressive method. Whatever strategy is employed, patients and families must be taught to maximize the individual's communicative strengths. Some treatment strategies are summarized below, in Table 5.

Table 5. Methods of Treating Aphasia (Open Table in a new window)

Method |

Characteristics |

Ideal For |

Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) |

Undamaged right hemisphere is recruited for language recovery by using melody-based therapy |

Nonfluent aphasia |

Amer-Ind Code |

Use of gestures that are associated with verbal labels |

Nonfluent aphasia |

Visual Communication Therapy |

Use of symbols to express needs and respond to questions |

Global aphasia |

Visual Action Therapy |

Use of pictures, drawings, and gestures to indicate objects |

Global aphasia |

Promoting Aphasics Communication Effectiveness (PACE) |

Encourages patients to convey information through any available modality (eg, speech, gestures, drawings, expressions, mime) |

Any |

Selected Cognitive-Communicative Disorders

Cognitive-communicative disorders affect the ability to communicate by impairing the pragmatics, or social rules, of language. [27] Cognitive processes involved include the following:

-

Orientation

-

Attention

-

Perception

-

Memory

-

Organization

-

Impulsivity

-

Reasoning

-

Recall

-

Planning and sequencing

-

Social behavior

Cognitive-communicative impairments occur primarily with the following 3 conditions:

-

Right hemispheric dysfunction

-

Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

-

Dementia

Right hemispheric dysfunction

Patients with right hemispheric lesions have relatively intact language but demonstrate impaired overall communication abilities. Common deficits seen in right hemispheric lesions are as follows:

-

Visuospatial processing

-

Insensitivity to context (missing subtleties)

-

Impulsivity

-

Difficulty with expression and reception of emotions

-

Lack of affective aspects (vocal inflection, facial expressions)

-

Impaired conversational rules (turn taking)

-

Left-sided neglect

-

Poor topic maintenance (tangential)

-

Unawareness of deficits

-

Failure to recognize humor

These impairments often cause patients to be considered difficult to get along with, rude, indifferent, or depressed.

Formal testing batteries for evaluating right hemispheric deficits can be administered by the SLP, including the RIC Evaluation of Communication Problems in Right Hemisphere Dysfunction (RICE) and the Mini Inventory of Right Brain Injury (MIRBI). Such batteries include analysis of the above deficits and assist the practitioner in deciding what treatment approaches to use.

Treatment of right hemispheric dysfunction tends to focus on behavior modification. The goal of treatment is to improve a patient's understanding of the context and pragmatics of communication. Importantly, family training to allow adjustments to and understanding of the patient's new personality is paramount to rehabilitation success.

Traumatic brain injury

Patients with TBI may experience a variety of communication disorders, including aphasia, dysarthria, apraxia, and stuttering. Most typical are disturbances of perception, behavior, information retrieval, memory, and executive functioning. Social difficulties are common due to impairment in social perceptiveness, self-regulation, emotional lability, and perseveration. Expressive language deficits often include confabulation, circumlocution, and verbosity.

Because patients with TBI often show deficits in perception, language, and memory, all of these modalities should be evaluated. As patients recover, they generally demonstrate progressive improvement in cognitive functioning. Because recovery is a dynamic process, patients with TBI should be tracked serially by a neuropsychologist to help guide the treatment plan.

Treatment of the cognitive-communicative deficits in patients with TBI requires special considerations. Most patients with TBI are aged younger than 30 years and have the potential to return to the workforce. Although initially the patient benefits from traditional rehabilitative techniques, he or she will require additional focus on areas of orientation, memory, attention, and self-regulation. Additionally, the patient's environment should be structured so that predictability reinforces memory. Lastly, generalization to real world settings is necessary during therapy if reentry into the community is to be successful.

Dementia

Dementia results in generalized intellectual impairment that compromises communication ability. A result of diffuse, bilateral damage, dementia may be cortical and/or subcortical. The severity of language impairment is associated with impairment in other mental functions. Patients with dementia often are classified into the following stages:

-

Early stage - The person is least affected; some difficulties with pragmatics, orientation, and word finding occur

-

Middle stage - Further deterioration from the above description is noted; additionally, disruption of grammar is present

-

Late stage - A progression to global impairment occurs, with all components of language affected; speech becomes mainly neologistic and echolalic and eventually disappears, with the patient becoming mute

Assessment of the demented patient should include a full history and physical examination, as well as formal testing. The Mini Mental Status examination can be administered quickly and easily. The SLP can administer the Arizona Battery for Communication Disorders of Dementia to assess communicative deficits. Assessment should be performed at regular intervals to follow the patient's progression.

Dementia is progressive and diffuse; therefore, treatment is supportive. Treatment goals should include environmental controls, capitalization on any preserved memory, and family training.

Hearing Impairment

As mentioned earlier, the ability to hear is an integral part of the normal communication process. An impaired ability to relate to sounds can result in social isolation, depression, avoidance, and diminished quality of life.

Frequencies used in the measurement of clinical hearing range from 250-8000Hz. The most critical part of this spectrum is the range of frequencies used for the reception and understanding of speech, 400-4000Hz.

Conductive hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss results from dysfunction of the outer and/or middle ear. Patients with conductive hearing loss usually can understand (discriminate) speech correctly but require louder volumes of speech. Possible causes of conductive hearing impairment include cerumen impaction, presence of a foreign body, tympanic membrane perforation, otitis media, and otosclerosis.

Sensorineural hearing loss

Sensorineural hearing loss results from dysfunction of the inner ear (cochlea) or of neural fibers of the eighth cranial nerve. Patients with sensorineural hearing loss usually have decreased speech discrimination. Conditions causing sensorineural impairment include excess noise, advanced age (presbycusis), ototoxic drugs, viral or bacterial illness, tumors, and cortical lesions.

Mixed and central hearing loss

A mixed hearing disorder involves components of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. Central hearing impairment results from dysfunction of the central auditory pathways (eg, tumors, demyelinating disease, vascular damage).

Evaluation of hearing loss

In general, conductive hearing is assessed by measuring sensitivity to sound waves vibrating through the air and moving from the external auditory canal and middle ear. Bone conduction is assessed by placing a vibrating tuning fork over the mastoid process. This maneuver bypasses the outer and middle ear and conducts sound vibrations directly to the cochlea. Therefore, it reflects the sensitivity of the sensorineural system.

The type and extent of hearing loss should be quantified further by audiometric screening by an otolaryngologist. Assessment includes measurements of air and bone conduction, as well as tests of speech discrimination.

Treatment and rehabilitation

In many cases of conductive or mixed hearing loss, the disease process can be reversed through proper treatment (eg, cerumen removal, tympanoplasty, myringotomy).

The most common rehabilitative therapy for hearing impairment is the hearing aid. Any person with hearing difficulties that limit daily activities should be considered a prospective candidate for a hearing aid. A hearing aid evaluation should be performed by a certified clinical audiologist. The use of a hearing aid does not cure the impairment, but it does improve the ability to communicate effectively. Successful hearing aid use is dependent on the patient's self-perceived impairment, acceptance of the device, and desire to use hearing amplification.

Cochlear implants are auditory prostheses that provide hearing for the profoundly deaf. The implant converts sound into electrical signals that are delivered directly to any viable eighth-nerve neurons in the cochlea. Sounds perceived with a cochlear implant are entirely different from the amplified sound heard with a hearing aid.

Assistive listening devices are used in selected listening environments. They employ a microphone placed close to the specific sound source, that transmits to the hearing-impaired listener. Assistive listening devices are effective in that they enhance the desired sound and diminish background noise. Other devices, such as closed-captioned television decoders, flashing alarms, telephone equipment, and tactile/vibration devices, are available.

Auditory training teaches the patient to be an assertive listener. Patients are instructed to inform others as to their most effective means of communication. The hearing-impaired person also is trained to use speech reading (recognizing facial expressions, gestures) to improve understanding of speech.

-

Classification of the aphasias.