Practice Essentials

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. It usually presents as bilateral symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects the hands and feet (see the image below). Any joint lined by a synovial membrane may be affected, however, and extra-articular involvement of organs such as the skin, heart, lungs, and eyes can be significant. RA is theorized to develop when a genetically susceptible individual (eg, a carrier of HLA-DR4 or HLA-DR1 [1] ) experiences an external factor (eg, cigarette smoking, infection, trauma) that triggers an autoimmune reaction.

Signs and symptoms

In most patients with RA, onset is insidious, often beginning with fever, malaise, arthralgias, and weakness before progressing to joint inflammation and swelling. Signs and symptoms of RA may include the following:

-

Persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) of hands and feet (hallmark feature)

-

Progressive articular deterioration

-

Extra-articular involvement

-

Difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs)

-

Constitutional symptoms

The physical examination should address the following:

-

Upper extremities (metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists, elbows, shoulders)

-

Lower extremities (ankles, feet, knees, hips)

-

Cervical spine

During the physical examination, it is important to assess the following:

-

Stiffness

-

Tenderness

-

Pain on motion

-

Swelling

-

Deformity

-

Limitation of motion

-

Extra-articular manifestations

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

No test results are pathognomonic; instead, the diagnosis is made by using a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging features. Potentially useful laboratory studies in suspected RA include the following:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

C-reactive protein level

-

Complete blood count

-

Rheumatoid factor assay

-

Antinuclear antibody assay

-

Anti−cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody

Potentially useful imaging modalities include the following:

-

Radiography (first choice): Hands, wrists, knees, feet, elbows, shoulders, hips, cervical spine, and other joints as indicated

-

Magnetic resonance imaging: Primarily cervical spine

-

Ultrasonography of joints: Joints, as well as tendon sheaths, for assessment of changes and degree of vascularization of the synovial membrane, and even erosions

Joint aspiration and analysis of synovial fluid may be considered, including the following:

-

Gram stain

-

Cell count

-

Culture

-

Assessment of overall appearance

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of RA should be initiated early, using shared decision making, an integrated approach that includes both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies, and a treat-to-target strategy. Treating to target is facilitated by use of the following:

-

American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommended RA disease activity measures [2]

-

ACR/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) criteria for remission [3]

Nonpharmacologic, nonsurgical therapies include the following:

-

Heat and cold therapies

-

Orthotics and splints

-

Therapeutic exercise

-

Occupational therapy

-

Adaptive equipment

-

Joint-protection education

-

Energy-conservation education

The following organizations have published guidelines for pharmacologic therapy:

-

American College of Rheumatology (2021) [4]

-

European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (2022) [5]

Nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) include the following:

-

Hydroxychloroquine

-

Azathioprine

-

Sulfasalazine

-

Methotrexate

-

Leflunomide

-

Cyclosporine

-

Gold salts

-

D-penicillamine

-

Minocycline

Biologic tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–inhibiting DMARDs include the following:

-

Etanercept

-

Infliximab

-

Adalimumab

-

Certolizumab

-

Golimumab

Biologic non-TNF DMARDs include the following:

-

Rituximab

-

Anakinra

-

Abatacept

-

Tocilizumab

-

Sarilumab

-

Tofacitinib

-

Baricitinib

-

Upadacitinib

Other drugs used therapeutically include the following:

-

Corticosteroids

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

Analgesics

Surgical treatments include the following:

-

Synovectomy

-

Tenosynovectomy

-

Tendon realignment

-

Reconstructive surgery or arthroplasty

-

Arthrodesis

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

The hallmark feature of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is persistent symmetric polyarthritis (synovitis) that affects the hands and feet, though any joint lined by a synovial membrane may be involved. Extra-articular involvement of organs such as the skin, heart, lungs, and eyes can be significant. (See Presentation.)

No laboratory test results are pathognomonic for RA, but the presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA; often tested as anti-CCP) and rheumatoid factor (RF) is highly specific for this condition. (See Workup.)

Optimal care of patients with RA requires an integrated approach that includes nonpharmacologic therapies and pharmacologic agents such as nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, and corticosteroids. (See Treatment, Guidelines, and Medication.)

Early therapy with DMARDs has become the standard of care; it not only can more efficiently retard disease progression than later treatment but also may induce more remissions. (See Treatment and Guidelines.) Many of the newer DMARD therapies, however, are immunosuppressive in nature, leading to a higher risk for infections. (See Treatment/Complications.)

Macrophage activation syndrome is a life-threatening complication of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) that necessitates immediate treatment with high-dose steroids and cyclosporine. (See Complications.)

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of RA is not completely understood. An external trigger (eg, cigarette smoking, infection, or trauma) that sets off an autoimmune reaction, leading to synovial hypertrophy and chronic joint inflammation along with the potential for extra-articular manifestations, is theorized to occur in genetically susceptible individuals.

The onset of clinically apparent RA is preceded by a period of pre-rheumatoid arthritis (pre-RA). The development of pre-RA and its progression to established RA has been categorized into the following phases [6] :

-

Phase I - Interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors of RA

-

Phase II - Production of RA autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP)

-

Phase III - Development of arthralgia or joint stiffness without any clinical evidence of arthritis

-

Phase IV – Development of arthritis in one or two joints (ie, early undifferentiated arthritis); if intermittent, the arthritis at this stage is termed palindromic rheumatism

-

Phase V - Established RA

Not all individuals will progress through the full sequence of phases, and current research is investigating ways to identify patients who are at risk of progression, and to delay or prevent RA in those patients. [7]

Synovial cell hyperplasia and endothelial cell activation are early events in the pathologic process that progresses to uncontrolled inflammation and consequent cartilage and bone destruction. Genetic factors and immune system abnormalities contribute to disease propagation.

CD4 T cells, mononuclear phagocytes, fibroblasts, osteoclasts, and neutrophils play major cellular roles in the pathophysiology of RA, and B cells produce autoantibodies (ie, rheumatoid factors). Abnormal production of numerous cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators has been demonstrated in patients with RA, including the following:

-

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)

-

Interleukin (IL)-1

-

IL-6

-

IL-8

-

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-ß)

-

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)

-

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)

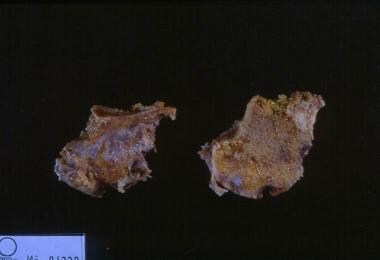

Ultimately, inflammation and exuberant proliferation of the synovium (ie, pannus) leads to destruction of various tissues, including cartilage (see the image below), bone, tendons, ligaments, and blood vessels. Although the articular structures are the primary sites involved by RA, other tissues are also affected.

Etiology

The cause of RA is unknown. Genetic, environmental, hormonal, immunologic, and infectious factors may play significant roles. Socioeconomic, psychological, and lifestyle factors may influence disease development and outcome.

Genetic factors

Genetic factors account for 50% of the risk for developing RA. [8] About 60% of RA patients in the United States carry a shared epitope of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 cluster, which constitutes one of the peptide-binding sites of certain HLA-DR molecules associated with RA (eg, HLA-DR beta *0401, 0404, or 0405). HLA-DR1 (HLA-DR beta *0101) also carries this shared epitope and confers risk, particularly in certain southern European areas. Other HLA-DR4 molecules (eg, HLA-DR beta *0402) lack this epitope and do not confer this risk.

Genes other than those of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are also involved. Results from sequencing genes of families with RA suggest the presence of several resistance and susceptibility genes, including PTPN22 and TRAF5. [9, 10] Researchers have identified more than 150 candidate loci with polymorphisms associated with RA, mainly related to seropositive disease. [11]

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), also known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), is a heterogeneous group of diseases that differs markedly from adult RA. JIA is known to have genetically complex traits in which multiple genes are important for disease onset and manifestations, and it is characterized by arthritis that begins before the age of 16 years, persists for more than 6 weeks, and is of unknown origin. [12] The IL2RA/CD25 gene has been implicated as a JIA susceptibility locus, as has the VTCN1 gene. [13]

Some investigators suggest that the future of treatment and understanding of RA may be based on imprinting and epigenetics. RA is significantly more prevalent in women than in men, [14, 15] which suggests that genomic imprinting from parents participates in its expression. [16, 17] Imprinting is characterized by differential methylation of chromosomes by the parent of origin, resulting in differential expression of maternal over paternal genes. [18]

Epigenetics is the change in DNA expression that is due to environmentally induced methylation and not to a change in DNA structure. Clearly, one research focus will be on environmental factors in combination with immune genetics. [11]

Infectious agents

For many decades, numerous infectious agents have been suggested as potential causes of RA, including Mycoplasma organisms, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), [19] and rubella virus. This suggestion is indirectly supported by the following evidence:

-

Occasional reports of flulike disorders preceding the start of arthritis

-

The inducibility of arthritis in experimental animals with different bacteria or bacterial products (eg, streptococcal cell walls)

-

The presence of bacterial products, including bacterial RNA, in patients’ joints

-

The disease-modifying activity of several agents that have antimicrobial effects (eg, gold salts, antimalarial agents, minocycline)

Emerging evidence also points to an association between RA and periodontopathic bacteria. For example, the synovial fluid of RA patients has been found to contain high levels of antibodies to anaerobic bacteria that commonly cause periodontal infection, including Porphyromonas gingivalis. [20, 21]

Hormonal factors

Sex hormones may play a role in RA, as evidenced by the disproportionate number of females with this disease, its amelioration during pregnancy, its recurrence in the early postpartum period, and its reduced incidence in women using oral contraceptives. Hyperprolactinemia may be a risk factor for RA. [22]

Lifestyle and occupational factors

Tobacco use is the main lifestyle risk factor for RA. [23] Genetic factors can further increase risk: a smoker with two copies of HLA-SE is at 40-fold higher risk of developing RA. In former smokers, risk may not return to the level of non-smokers for up to 20 years after smoking cessation. [6]

Dietary risk factors for RA include the following [6] :

-

Red meat intake

-

Vitamin D deficiency

-

Excessive coffee consumption

-

High salt intake

A review of data from the Nurses' Health Study, which assessed 5 lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, physical activity, and diet), found that a healthier lifestyle was associated with lower risk of RA. The population attributable risk estimate was that 34% of incident RA was preventable if participants adopted ≥4 healthy lifestyle factors. [24]

Occupational risk

Schmajuk et al reported a strong association between coal mining, and other dusty trades involving silica exposure, with RA. For those in the highest-intensity ergonomic exposure group, the odds ratio for RA was 4.3. [25]

Immunologic factors

All of the major immunologic elements play fundamental roles in initiating, propagating, and maintaining the autoimmune process of RA. The exact orchestration of the cellular and cytokine events that lead to pathologic consequences (eg, synovial proliferation and subsequent joint destruction) is complex, involving T and B cells, antigen-presenting cells (eg, B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells), and various cytokines. Aberrant production and regulation of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and cytokine pathways are found in RA.

T cells are assumed to play a pivotal role in the initiation of RA, and the key player in this respect is assumed to be the T helper 1 (Th1) CD4 cells. (Th1 cells produce IL-2 and interferon [IFN] gamma.) These cells may subsequently activate macrophages and other cell populations, including synovial fibroblasts. Macrophages and synovial fibroblasts are the main producers of TNF-a and IL-1. Experimental models suggest that synovial macrophages and fibroblasts may become autonomous and thus lose responsiveness to T-cell activities in the course of RA.

B cells are important in the pathologic process and may serve as antigen-presenting cells. B cells also produce numerous autoantibodies (eg, RF and ACPA) and secrete cytokines.

The hyperactive and hyperplastic synovial membrane is ultimately transformed into pannus tissue and invades cartilage and bone, with the latter being degraded by activated osteoclasts. The major difference between RA and other forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as psoriatic arthritis, lies not in their respective cytokine patterns but, rather, in the highly destructive potential of the RA synovial membrane and in the local and systemic autoimmunity.

Whether these 2 events are linked is unclear; however, the autoimmune response conceivably leads to the formation of immune complexes that activate the inflammatory process to a much higher degree than normal. This theory is supported by the much worse prognosis of RA among patients with positive RF results.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, the annual incidence of RA is approximately 3 cases per 10,000 population, and the prevalence rate is approximately 1%, increasing with age and peaking between the ages of 35 and 50 years. RA affects all populations, though it is much more prevalent in some groups (eg, 5-6% in some Native American groups) and much less prevalent in others (eg, Black persons from the Caribbean region).

First-degree relatives of individuals with RA are at 2- to 3-fold higher risk for the disease. Disease concordance in monozygotic twins is approximately 15-20%, suggesting that nongenetic factors play an important role. Because the worldwide frequency of RA is relatively constant, a ubiquitous infectious agent has been postulated to play an etiologic role.

Women are affected by RA approximately 3 times more often than men are. [14, 15] For example, a nationwide study from Norway reported that the point prevalence of RAl was 1.10% in women and 0.46% in men. [26] However, sex differences in RA diminish in older age groups. [14] In investigating whether the higher rate of RA among women could be linked to certain reproductive risk factors, a study from Denmark found that the rate of RA was higher in women who had given birth to just 1 child than in women who had delivered 2 or 3 offspring. [27] However, the rate was not increased in women who were nulliparous or who had a history of lost pregnancies.

Time elapsed since pregnancy is also significant. In the 1- to 5-year postpartum period, a decreased risk for RA has been recognized, even in those with higher-risk HLA markers. [28]

The Danish study also found a higher risk of RA among women with a history of preeclampsia, hyperemesis during pregnancy, or gestational hypertension. [27] In the authors’ view, this portion of the data suggested that a reduced immune adaptability to pregnancy may exist in women who are predisposed to the development of RA or that there may be a link between fetal microchimerism (in which fetal cells are present in the maternal circulation) and RA. [27]

Prognosis

The clinical course of RA is generally one of exacerbations and remissions. Approximately 40% of patients with this disease become disabled after 10 years, but outcomes are highly variable. [29] Some patients experience a relatively self-limited disease, whereas others have a chronic progressive illness.

Prognostic factors

Outcome in RA is compromised when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Intervention with DMARDs in very early RA (symptom duration < 12 weeks at the time of first treatment) provides the best opportunity for achieving disease remission. [30] Better detection of early joint injury has provided a previously unappreciated view of the ubiquity and importance of early joint damage. Nonetheless, predicting the long-term course of an individual case of RA at the outset remains difficult, though the following all correlate with an unfavorable prognosis in terms of joint damage and disability:

-

HLA-DRB1*04/04 genotype

-

High serum titer of autoantibodies (eg, RF and ACPA)

-

Extra-articular manifestations

-

Large number of involved joints

-

Age younger than 30 years

-

Female sex

-

Systemic symptoms

-

Insidious onset

In a retrospective study that used logistic regression to analyze clinical and laboratory assessments in patients with RA who took only methotrexate, the authors found that measures of C-reactive protein (CRP) and swollen joint count after 12 weeks of methotrexate administration were most associated with radiographic progression at week 52. [31]

The prognosis of RA is generally much worse among patients with positive RF results. For example, the presence of RF in sera has been associated with severe erosive disease. [32, 33] However, the absence of RF does not necessarily portend a good prognosis.

Other laboratory markers of a poor prognosis include early radiologic evidence of bony injury, persistent anemia of chronic disease, elevated levels of the C1q component of complement, and the presence of ACPA (see Workup). In fact, the presence of ACPA and antikeratin antibodies (AKA) in sera has been linked with severe erosive disease, [32] and the combined detection of these autoantibodies can increase the ability to predict erosive disease in RA patients. [33]

RA that remains persistently active for longer than 1 year is likely to lead to joint deformities and disability. [34] Periods of activity lasting only weeks or a few months followed by spontaneous remission portend a better prognosis.

A study by Mollard et al of 8189 women in a US-wide observational cohort who developed RA before menopause found greater functional decline in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal ones; furthermore, the trajectory of functional decline worsened and accelerated after menopause. However, ever-use of hormonal replacement therapy, ever having a pregnancy, and longer length of reproductive life were associated with less functional decline. [35]

Morbidity and mortality

Most data on RA disability rates derive from specialty units caring for referred patients with severe disease. Little information is available on patients cared for in primary care community settings. Estimates suggest that more than 50% of these patients remain fully employed, even after 10-15 years of disease, with one third having only intermittent low-grade disease and another one third experiencing spontaneous remission.

A systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the relative risk of cardiovascular events in patients with RA was 1.55. [36] RA is associated with traditional and nontraditional cardiovascular risk factors. The leading cause of excess mortality in RA is cardiovascular disease, followed by infection, respiratory disease, and malignancies. The effects of concurrent therapy, which is often immunosuppressive, may contribute to mortality in RA. However, studies suggest that control of inflammation may improve survival.

Nontraditional risk factors appear to play an important role in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Myocardial infarction, myocardial dysfunction, and asymptomatic pericardial effusions are common; symptomatic pericarditis and constrictive pericarditis are rare. Myocarditis, coronary vasculitis, valvular disease, and conduction defects are occasionally observed. A large Danish cohort study suggested an increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke in patients with RA. [37]

Patients with RA are at significantly elevated risk for lymphoma, likely due to chronic inflammatory stimulation of the immune system. [38] A study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data documented an increased risk for cancer in general in patients with RA. with an odds ratio of 1.632. [39] In contrast, an earlier study of 84,475 RA patients in California concluded that females were at significantly decreased risk for several cancers, including breast, ovary, uterus, cervix, and melanoma, while males had significantly higher risks of lung, liver, and esophageal cancer, but a lower risk of prostate cancer. [40]

The overall mortality in patients with RA is reportedly 2.5 times higher than that of the general age-matched population. In the 1980s, mortality among those with severe articular and extra-articular disease approached that among patients with 3-vessel coronary disease or stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Much of the excess mortality derives from infection, vasculitis, and poor nutrition.

Patient Education

Patient education and counseling help to reduce pain and disability and the frequency of physician visits. These may represent the most cost-effective intervention for RA. [41, 42]

Informing patient of diagnosis

With a potentially disabling disease such as RA, the act of informing the patient of the diagnosis takes on major importance. The goal is to satisfy the patient’s informational needs regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment in appropriate detail. To understand the patient’s perspective, requests, and fears, the physician must employ careful questioning and empathic listening.

Telling patients more than they are intellectually or psychologically prepared to handle (a common mistake) risks making the experience so intense as to trigger withdrawal. Conversely, failing to address issues of importance to the patient compromises the development of trust. The patient needs to know that the primary physician understands the situation and is available for support, advice, and therapy as the need arises. Encouraging the patient to ask questions helps to communicate interest and caring.

Discussing prognosis and treatment

Patients and families do best when they know what to expect and can view the illness realistically. Many patients fear crippling consequences and dependency. Accordingly, it is valuable to provide a clear description of the most common disease manifestations. Without encouraging false hopes, the physician can point out that spontaneous remissions can occur, a sizeable portion of patients achieve remission with therapy, and more than two thirds of patients live independently without major disability. In addition, emphasize that much can be done to minimize discomfort and to preserve function.

A review of available therapies and their efficacy helps patients to overcome feelings of depression stemming from an erroneous expectation of inevitable disability. [43] Even in those with severe disease, guarded optimism is now appropriate, given the host of effective and well-tolerated disease-modifying treatments that have become available.

Dealing with misconceptions

Several common misconceptions regarding RA deserve attention. Explaining that no known controllable precipitants exist helps to eliminate much unnecessary guilt and self-recrimination. Dealing in an informative, evidence-based fashion with a patient who expresses interest in alternative and complementary forms of therapy can help limit expenditures on ineffective treatments.

Another misconception is that a medication must be expensive to be helpful. Generic NSAIDs, low-dose prednisone, [29] and the first-line DMARDs are quite inexpensive yet remarkably effective for relieving symptoms, a point that bears emphasizing. The belief that one must be given the latest TNF inhibitor to be treated effectively can be addressed by a careful review of the overall treatment program and the proper role of such agents in the patient’s plan of care.

Active participation of the patient and family in the design and implementation of the therapeutic program helps boost morale and to ensure compliance, as does explaining the rationale for the therapies used.

The family also plays an important part in striking the proper balance between dependence and independence. Household members should avoid overprotecting the patient (eg, the spouse refraining from intercourse out of fear of hurting the patient) and should work to sustain the patient’s pride and ability to contribute to the family. Allowing the patient with RA to struggle with a task is sometimes constructive.

Supporting patient with debilitating disease

Abandonment is a major fear in these individuals. Patients are relieved to know that they will be closely observed by the primary physician and healthcare team, working in conjunction with a consulting rheumatologist and physical/occupational therapist, all of whom are committed to maximizing the patient’s comfort and independence and to preserving joint function. With occupational therapy, the treatment effort is geared toward helping the patient maintain a meaningful work role within the limitations of the illness.

Persons with long-standing severe disease who have already sustained much irreversible joint destruction benefit from an emphasis on comfort measures, supportive counseling, and attention to minimizing further debility. Such patients need help in grieving for their disfigurement and loss of function.

An accepting, unhurried, empathic manner allows the patient to express feelings. The seemingly insignificant act of touching does much to restore a sense of self-acceptance. Attending to pain with increased social support, medication, and a refocusing of attention to function is useful. A trusting and strong patient-doctor relationship can do much to sustain a patient through times of discomfort and disability.

For more information, see the Arthritis Center, as well as Rheumatoid Arthritis, Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis Medications.

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Ankylosis in the cervical spine at several levels due to long-standing juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (also known as juvenile idiopathic arthritis).

-

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Widespread osteopenia, carpal crowding (due to cartilage loss), and several erosions affecting the carpal bones and metacarpal heads in particular in a child with advanced juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (also known as juvenile idiopathic arthritis).

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid changes in the hand. Photograph by David Effron MD, FACEP.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid nodules at the elbow. Photograph by David Effron MD, FACEP.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Soft-tissue swelling and early erosions in the proximal interphalangeal joints in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis of the hands.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Subluxation in the metacarpophalangeal joints, with ulnar deviation, in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis of the hands.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Coronal, T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scan shows characteristic pannus and erosive changes in the wrist in a patient with active rheumatoid arthritis. Courtesy of J. Tehranzadeh, MD, University of California at Irvine.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lateral view of the cervical spine in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis shows erosion of the odontoid process.

-

Boutonniere deformity.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Anteroposterior radiograph of the knee shows uniform joint-space loss in the medial and lateral knee compartments without osteophytosis. A Baker cyst is seen medially (arrowhead).

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Ultrasonography-guided synovial biopsy of the second metacarpophalangeal joint of the right hand in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis of the hands. The biopsy needle is seen as a straight echogenic line on the left side of the image in an oblique orientation.

-

Plain lateral radiograph of the normal cervical spine taken in extension shows measurement of anterior atlantodental interval (yellow line) and posterior atlantodental interval (red line).

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lateral flexion view of the cervical spine shows atlantoaxial subluxation.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lateral view of the cervical spine in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis shows erosion of the odontoid process.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. T1-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance image of the cervical spine shows basilar invagination with cranial migration of an eroded odontoid peg. There is minimal pannus. The tip of the peg indents the medulla, and there is narrowing of the foramen magnum due to the presence of the peg. Inflammatory fusion of several cervical vertebral bodies is shown.

-

Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of cervical spine in same patient as in previous image. Compromised foramen magnum is easily appreciated, and there is increased signal intensity within upper cord; this is consistent with compressive myelomalacia. Further narrowing of canal is seen at multiple levels.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lateral radiograph of the same patient as in Images 4-5. Midcervical vertebral-body fusions are shown. The eroded peg is difficult to visualize, but inferior subluxation of the anterior arch of C1 is shown.

-

Lateral radiograph of a normal cervical spine shows the McGregor line. The odontoid tip should not protrude more than 4.5 mm above the line, which is drawn from the posterior edge of the hard palate to the most caudal point of the occiput.

-

Normal lateral magnified radiograph of the cervical spine shows the Ranawat method of detection of cranial settling. This method is used to measure the distance from the center of the pedicles (sclerotic ring) of C2 to a line drawn connecting the midpoints of the anterior and posterior arches of C1. (Normal values are 15 mm or greater for males and 13 mm or greater for females.)

-

Lateral radiograph of the cervical spine shows how the cervical height index (CHI) is calculated. The distance from the center of the sclerotic ring of C2 to the tip of the spinous process of C2 (dotted line) is measured. This is then divided into the distance from the center of the sclerotic ring of C2 to the midpoint of the inferior border of the body of C7. A CHI of less than 2 mm is a sensitive predictor of neurologic deficit.

-

X-ray shows total hip replacement, with prosthesis, in patient with osteoarthritis.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. This gross photo shows destruction of the cartilage and erosion of the underlying bone with pannus from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. The hallmark of rheumatoid arthritis is a perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate in the synovium (pictured here). The early stages are noted to have plasma cells as well, and syphilis needs to be part of the differential diagnosis.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. The inflammation involved in rheumatoid arthritis can be intense. It is composed of mononuclear cells and can resemble a pseudosarcoma.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. A 72-year-old man with long-standing rheumatoid arthritis developed blue-grayish discoloration of his skin. He had been on hydroxychloroquine for approximately 15 years. The diagnosis was hydroxychloroquine-related hyperpigmentation. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. A 64-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis has developed nodules on the dorsal and volar aspect of her fingers, as well as the posterior aspect of her heels. The diagnosis is rheumatoid nodules with methotrexate-induced accelerated nodulosis. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis. A 64-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis has developed nodules on the dorsal and volar aspect of her fingers, as well as the posterior aspect of her heels. The diagnosis is rheumatoid nodules with methotrexate-induced accelerated nodulosis. Image courtesy of Jason Kolfenbach, MD, and Kevin Deane, MD, Division of Rheumatology, University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.