Overview

Osteoporosis and osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are commonly encountered clinical problems. The definition of osteoporosis is diminished bone density measuring 2.5 standard deviations below the average bone density of healthy, 25-year-old, same-sex members of the population. In the United States, approximately 35% of women older than 65 years have osteoporosis.

Vertebral compression fracture (seen in the image below) is the most common complication of osteoporosis. Approximately 700,000 new vertebral compression fractures occur every year in the United States alone, accounting for 70,000 hospital admissions and resulting in $15 billion in annual costs. [1]

Go to Osteoporosis and Pediatric Osteoporosis for more complete information on this topic.

Most patients experiencing an osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture remain asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic; however, a large number of these patients do experience significant pain, resulting in decreased quality of life and disability. Conventional medical treatment for these patients includes pain medication, activity limitation, physical therapy, and (possibly) bracing. [2, 3]

Patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are usually treated nonoperatively.

Types of vertebral compression fractures

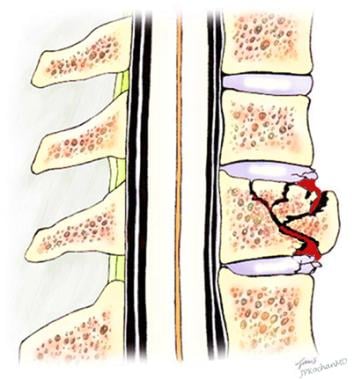

Vertebral compression fractures characteristically demonstrate a wedge-shaped pattern (seen in the images below) with gross collapse of the anterior portion of the vertebral body and relative preservation of the posterior body height.

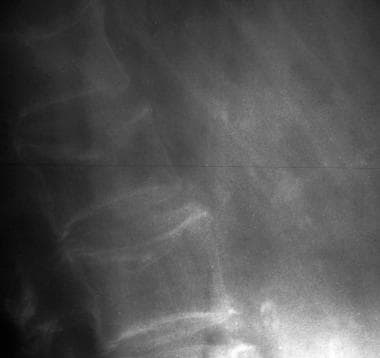

Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

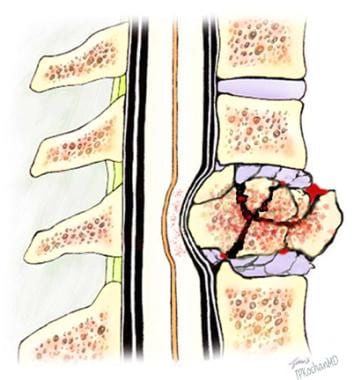

A second common form of fracture is a central crush fracture, which frequently occurs in the lower lumbar spine. Increased interpedicular space, involvement of the posterior cortex, or laminar fracture suggest a burst fracture (seen in the image below), which may be unstable.

Etiology of osteoporotic compression fractures

Cortical and trabecular bone loss, as well as disruption of the microarchitecture of bone, are all typical of osteoporosis. Spinal flexion and axial compression have been shown to place maximal stress on the superior endplate of the vertebral body. The asymmetry of the vertebral body produces maximal stress at the anterior aspect of the cortical shell.

A combination of these factors, that is, decreased, asymmetrical, and irregular bone density, is a hallmark of osteoporotic bone loss. Coupled with even minimal flexion and/or axial loading, these factors predispose the osteoporotic vertebrae to wedge-shaped compression fractures, acquired kyphosis, and general height loss.

Once 1 vertebral compression fracture has occurred, a biomechanical environment is created that favors additional fractures. This occurs as a result of the vertebral compression fracture causing an additional kyphosis, shifting the patient's center of gravity anteriorly and producing a longer moment arm. This longer moment arm increases kyphotic angulation and places additional stress on the vertebrae, particularly the vertebrae adjacent to the primary fracture.

Progressive kyphosis, additional fractures, and neurologic changes are potential complications of osteoporotic compression fractures. These complications can be minimized with appropriate, expeditious care.

All vertebral compression fractures require a systematic examination to rule out an underlying systemic illness, such as malignancy, infection, or renal or liver disease.

Treatment Assessment

The critical element in deciding a treatment regimen is pain and percentage of vertebral collapse. If a patient rates his/her pain as being greater than 4 out of 10 (if 10 equals the worst pain imaginable and 0 equals no pain) or the vertebral bodies are collapsed more than 40%, then kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty is indicated as a potential intervention. Other patients may initially attempt more conservative care. [4]

Nonoperative Therapies

According to American College of Radiology (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria for the management of vertebral compression fractures, updated in 2013, conservative management is the traditional first-line therapy for painful vertebral compression fractures. In most patients, according to the ACR, pain from these fractures resolves spontaneously, even without medication use. [5]

Physical therapy

Heat, massage, analgesic medications, and bed rest may provide symptomatic relief. (However, bed rest and immobilization can cause disuse, osteopenia, and an increased risk of a thromboembolic event.)

Bracing used to be common. However, the use of extension bracing has become controversial because of concerns regarding the placement of increased stress on the posterior elements of the spine.

A prospective, randomized, multicenter study by Kato et al of patients with acute, one-level osteoporotic compression fractures who did undergo bracing found that, at 48-week follow-up, the results of 12 weeks of treatment with a rigid brace did not differ statistically from those of 12-week soft-brace treatment with regard to quality of life, back pain, or prevention of spinal deformity. [6]

A structured exercise program is essential and should be tailored to enhance axial muscle strength. Early mobilization should be employed to prevent secondary complications of immobility. Back strengthening exercises may improve kyphotic deformity. [7] Back extension exercises should be used preferentially over abdominal flexion exercises. [8, 9]

Weight-bearing exercises are considered the mainstay of therapy to prevent extension of osteoporosis. Crunches and sit-ups should be excluded. Many consider Pilates to be an excellent physical exercise regimen. If balance is impaired, Tai Chi Chuan is recommended as a means of helping the patient to prevent falls.

A prospective cohort study by Nagaoka et al indicated that functional recovery tends to be decreased and hospital stay longer in older patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures who have low handgrip strength on hospital admission. The investigators suggested that outcome improvement in these fractures could be aided through early detection of and intervention for low handgrip strength. [10]

Occupational therapy

This is primarily used in an inpatient setting.

Recreational therapy

This is primarily used in an inpatient setting. Along with occupational therapy, recreational therapy is an important component of a patient's transition from an inpatient setting to an outpatient setting.

Pharmacologic therapy

Patients should be treated for their osteoporosis with appropriate anti-osteoporotic medications (among which, second-generation bisphosphonate should be considered), as well as with (daily) 1500 mg of elemental calcium and 400-800 IU of vitamin D. Miacalcin may be taken intranasally and has been purported to reduce the pain from compression fractures.

A retrospective study by Iwata et al of patients undergoing conservative management of recent single-level osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures indicated that teriparatide (recombinant human parathyroid hormone 1-34) is associated with a significantly higher radiographic union rate than bisphosphonate (89% vs 68%, respectively) by 6-month follow-up, as well as a significantly shorter time-to-union. However, teriparatide was not found to contribute to the prevention of vertebral deformity progression. [11]

Oral medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and narcotics [5] have many roles in the treatment of patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures.

Pain relief is of paramount concern. Pain medications may be used for a short period, typically 1-2 months. However, if pain requiring medication persists for longer than 1 month, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty may be considered. If pain medications do not provide adequate pain relief during the first month, these procedures should be considered sooner.

As always, the benefits of the medications need to be weighed against the adverse effects. Anti-inflammatory medications may produce adverse gastrointestinal effects.

Analgesic medications are often poorly tolerated, especially in elderly patients. Strong analgesic drugs may cause confusion, disorientation, increased risk of falling, constipation, and respiratory depression.

A study by Malacon et al indicated that following low-energy vertebral compression fractures, osteoporosis is being undertreated. The report found that out of 143,081 patients aged 50 years or older who were diagnosed with primary closed thoracolumbar vertebral compression fracture without neurologic injury, 16,780 (11.7%) began anti-osteoporotic medication within a year. The study, which encompassed diagnoses of vertebral compression fracture between 2004 and 2019, determined that the percentage of patients undergoing anti-osteoporotic medication therapy within a year post fracture peaked in 2008, at 15.2%, declined until 2012, and then modestly increased again. [12]

Indications for and Pitfalls of Surgical Intervention

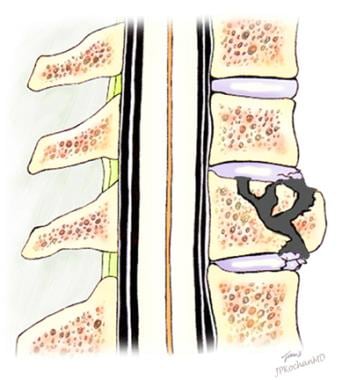

The two main minimally invasive surgical procedures for osteoporotic compression fractures are kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. (Kyphoplasty is seen in the first 2 images below; vertebroplasty is seen in the third image). [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]

Patients with compression fractures that do not compromise the spinal canal can be treated by means of a kyphoplasty. The use of a percutaneous balloon allows for expansion of the fractured vertebrae. The void created by the balloon is then filled with bone cement.

Patients with compression fractures that do not compromise the spinal canal can be treated by means of a kyphoplasty. The use of a percutaneous balloon allows for expansion of the fractured vertebrae. The void created by the balloon is then filled with bone cement.

Vertebroplasty. Anterior wedge compression fracture after fusion of the fracture fragments with polymethylmethacrylate.

Vertebroplasty. Anterior wedge compression fracture after fusion of the fracture fragments with polymethylmethacrylate.

More aggressive surgical intervention in an osteoporotic spine is fraught with difficulties. Advanced patient age, the presence of comorbid diseases, and difficulty in securing fixation to weakened osteoporotic bone make surgical intervention an absolute last resort.

However, surgical intervention may be required in patients with neurologic impairment, such as paresis, paralysis, saddle anesthesia, or bowel or bladder changes. Surgical intervention may also be required in a patient who is clinically unimproved despite adequate conservative care. [13, 14, 15]

Surgery may be indicated in a patient with radiographic evidence of instability. This is exhibited by ligamentous disruption with potential pending canal compromise or when movement is exhibited on dynamic or motion radiographic examination. [24]

The advancement of kyphosis despite adequate conservative care may also be an indication for surgery.

According to the 2018 revision of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria for vertebral compression fracture management, evidence indicates that, compared with conservative therapy for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures, vertebral augmentation (such as percutaneous vertebroplasty and balloon-assisted kyphoplasty) can provide better pain relief and functional outcomes. [25]

Patient Consultations

In patients with an underlying systemic disease, appropriate medical consultations are required.

Consulting a physiatrist is appropriate, and consultation can help to assess functional limitations.

A rheumatologist is an appropriate consultation for osteoporosis management.

Consulting an orthopedic surgeon or a neurosurgeon is appropriate if surgery is being considered. [26]

Indications for Inpatient Care

Inpatient care is not generally required for patients with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. However, if neurologic injury has occurred and/or another underlying systemic disease has been detected, inpatient care may be appropriate.

Transfer to an inpatient facility is also indicated for patients who are unable to care for themselves at home.

Patient Follow-up

Serial radiographs should be obtained for 1 year following injury to be sure no kyphotic progression has occurred.

Fracture Prevention

In addition to taking anti-osteoporotic medications, as well as (daily) 1500 mg of elemental calcium and 400-800 IU of vitamin D, patients should be taught to modify their activities by employing fall-prevention strategies. (Fifty percent of patients with painful vertebral fractures give a history of a recent fall.)

The results of a study by Bischoff-Ferrari et al indicated that vitamin D offers dose-dependent protection against fractures, with doses of more than 400 IU per day reducing fractures by at least 20% in individuals aged 65 years or older. Calcium supplementation was reported not to have affected the results. [27]

A patient with a painful vertebral compression fracture typically describes an abrupt onset of pain during an atraumatic, low-exertion activity, such as coughing or sneezing. Therefore, patients should be given the pneumococcal vaccine and undergo yearly influenza vaccinations to reduce their risk of severe coughing (which can result in a vertebral compression fracture).

Patients should be instructed in proper weight-bearing exercises and extension exercises.

For patient education information, see eMedicineHealth's Osteoporosis Center, as well as Osteoporosis, Osteoporosis Medications, and Vertebral Compression Fracture.

-

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of an L1 osteoporotic wedge compression fracture.

-

Patients with compression fractures that do not compromise the spinal canal can be treated by means of a kyphoplasty. The use of a percutaneous balloon allows for expansion of the fractured vertebrae. The void created by the balloon is then filled with bone cement.

-

Anterior wedge compression fracture with an intact posterior vertebral cortex.

-

Osteoporotic spine. Note the considerable reduction in overall bone density and the lateral wedge fracture of L2.

-

A vertebral burst fracture.

-

Vertebroplasty. Anterior wedge compression fracture after fusion of the fracture fragments with polymethylmethacrylate.

-

Fluoroscopic view of a kyphoplasty procedure.