Practice Essentials

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD) is fecal incontinence or constipation resulting from central nervous system (CNS) disease or injury. [1, 2] Common causes of NBD include spinal cord injury (SCI), [3] amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spina bifida, [4] myelomeningocele (MMC), multiple sclerosis (MS), [5] Parkinson disease (PD), stroke, diabetes mellitus, and cerebral palsy or other diagnoses with truncal hypotonia.

NBD results from loss of normal sensory or motor control and may encompass both the upper and the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Quality of life is greatly affected; patients often find their symptoms to be socially disabling. Although bowel dysfunction is a common event, to date there have been relatively few studies addressing bowel management.

Incontinence and evacuation can be investigated by tests that assess sphincter structure and function, such as anorectal manometry and endoanal ultrasonography (EAUS). Anorectal and pelvic floor function can be assessed by means of defecating proctography and nerve conduction studies. Luminal integrity and colonic function can be evaluated by means of endoscopy and transit studies. (See Workup.)

Treatment of NBD is initially conservative and may involve a variety of nonoperative approaches. Patients with suspected bowel rupture or perforation should be transferred to surgical care, as should any patients with rectal prolapse. (See Treatment.)

Anatomy

The colon is a muscular tube 1.5 m long, and the rectum is 12-15 cm long. The rectum opens to the outside through the anal canal, which is 2-5 cm long. The anus contains the internal anal sphincter, which is composed of smooth muscle and is not under voluntary control, and the external sphincter, which is composed of skeletal voluntary muscle. [6]

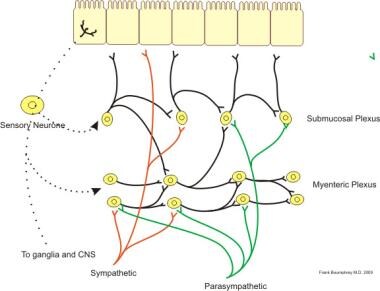

The intrinsic nervous system, also known as the enteric nervous system, is composed of the submucosal (ie, Meissner) and myenteric (ie, Auerbach) plexuses (see the image below), which largely regulate segment-to-segment movement of the GI tract.

Illustration of neural control of gut wall by sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous system. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of neural control of gut wall by sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous system. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The extrinsic nervous supply comprises the parasympathetic, sympathetic, and somatic nerves. The vagus nerve is parasympathetic and innervates the upper segments of the GI tract up to the splenic flexure. The pelvic splanchnic nerves carry parasympathetic fibers from the S2-4 spinal cord levels to the descending colon and rectum.

Sympathetic innervation comes from the superior and inferior mesenteric nerves (T9-12) and the hypogastric nerve (T12-L2). The hypogastric nerve sends out sympathetic innervation from the L1, L2, and L3 spinal segments to the lower colon, rectum, and sphincters. The somatic pudendal nerve (S2-4) innervates the pelvic floor and the external anal sphincter. [7]

Pathophysiology

Normal bowel function

Fecal contents are propelled in the large intestine by periodic mass movements, and defecation is initiated by involuntary peristaltic advancement of stool into the rectum. An awareness of the need to defecate occurs in the superior frontal gyrus and anterior cingulate gyrus of the cerebral cortex, as a result of a critical level of rectal filling. The rectum stores stool until it is full; fullness stimulates pressure receptors on the pelvic floor that trigger the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, allowing internal anal sphincter relaxation.

The external sphincter is normally contracted until it is voluntarily relaxed; this relaxation reduces pressure and thus permits defecation. The Valsalva maneuver, a voluntary contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, raises intra-abdominal pressure and triggers peristalsis in the colon and rectum, causing relaxation of the internal sphincter. When rectal pressure exceeds sphincter pressure, defecation occurs. [8, 9]

Bowel dysfunction

Injury to and disorders of the CNS affect bowel function in various ways, depending on the location and severity of the damage.

Spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, and myelomeningocele

The pathophysiology of NBD is much the same for SCI, MS, and MMC, even though the nature of the insult differs. Traumatic SCIs are usually well defined, whereas MS lesions may be found at multiple sites, and most patients with MMC have low spinal cord lesions, often at the conus medullaris or the cauda equina. [10]

Spinal cord lesions are classified as either located above the conus medullaris or located at the conus medullaris/cauda equina. A spinal cord lesion above the conus medullaris is an upper-motor-neuron (UMN) lesion. It causes loss of voluntary control, maintained reflex activity in the anorectum, increased colonic transit time, and constipation. Anal tone is increased or maintained.

A lesion at the level of the conus medullaris, the cauda equina, or the inferior splanchnic nerve is considered a lower-motor-neuron (LMN) lesion. It causes loss of voluntary control, loss of reflex activity in the anorectum, prolonged transit time, constipation and rectal impaction, and reduced resting tone in the anal sphincter. [11]

Spina bifida is also associated with significant bowel issues.

Parkinson disease

The pathophysiology of bowel dysfunction in PD is characterized by dystonia of striated muscles of the pelvic floor and the external anal sphincter. Colonic transit time is prolonged as a consequence of loss of dopamine within the CNS and the enteric nervous system. [10]

Brain lesions

Patients with brain lesions and survivors of stroke have bowel dysfunction caused by loss of inhibition of the sacral reflex. [12]

Cerebral palsy can be assoicated with bowel dysfunction as well.

Diabetes mellitus

Patients with diabetes may have fecal incontinence as a consequence of irreversible damage of the autonomic nervous system and impaired rectal sensation. Both motor and sensory dysfunction may occur. [12]

Epidemiology

The frequency of fecal incontinence and constipation ranges from approximately 1% to as much as 25% of the general adult population, depending on how the terms are defined. [13, 14, 15, 16] However, bowel dysfunction occurs in most people with neurologic conditions.

Approximately 12,000 new cases of SCI occur in the United States each year, most of them caused by trauma. Bowel dysfunction affects almost all patients with a chronic SCI, with as many as 95% reporting constipation and as many as 75% experiencing fecal incontinence. [17, 18]

MS is diagnosed in young adults and more often in women. Its prevalence is approximately 1 per 1000 individuals, and as many as 70% experience constipation, incontinence, or both. [19, 20] PD affects 1 million people in the US each year, with constipation occurring in 37%. [21] About 25% of stroke survivors experience constipation, and 15% have fecal incontinence. [22, 23]

The age of incidence is variable. No known sexual or racial predilection has been reported for this condition.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the severity, location, and presenting comorbid factors in patients with SCI. Patients with complete SCI have a less favorable prognosis. Because of the chronic nature of NBD, it is a significant contributor to reduced quality of life. Patients with SCI have reported that bowel dysfunction is more problematic than bladder dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, pain, fatigue, or perception of body image. [18] Additionally, hospitalizations due to impaction, megacolon, constipation and volvulus are more than twice as frequent in these patients. [24]

A study by Ozisler et al found that an effective bowel program reduced the severity of NBD and lowered the incidence of associated GI problems in SCI patients. [25]

Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding the long-term management of bowel dysfunction, particularly with respect to the rationale, goals, and techniques of management. They should be instructed in the safe use of assistive devices for bowel emptying and taught efficient techniques for bowel emptying, digital stimulation, and the use of rectal suppositories.

The importance of timing, regularity, and positioning in bowel evacuation should be emphasized. Recommendations for helping prevent bowel-related complications (eg, constipation, hemorrhoids, and impaction) should be provided.

-

Administration of an enema.

-

Illustration of neural control of gut wall by sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous system. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

-

Colonoscopy reveals diverticulosis (pockets within colon that can bleed or become infected). Video courtesy of Dawn Sears, MD, and Dan C Cohen, MD, Division of Gastroenterology, Scott & White Healthcare.

-

Abdominal X-ray showing fecal impaction extending from pelvis upward to left subphrenic space and from left toward right flank, measuring over 40 cm in length and 33 cm in width. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons