Overview

Initial evaluation and management of small and moderate burns is a routine part of general plastic surgery practice. An ability to accurately evaluate and provide proper initial care for these injuries is essential.

Outcomes for patients with burns have improved dramatically over the past 20 years, but burns still cause substantial morbidity and mortality. Proper evaluation and management, coupled with appropriate early specialty referral, greatly help in minimizing suffering and optimizing results. [1]

The image below depicts burn blisters on a child's hand.

Management of burn blisters is controversial. Burn blisters occasionally obscure the presence of full-thickness wounds.

Management of burn blisters is controversial. Burn blisters occasionally obscure the presence of full-thickness wounds.

A study by Nurczyk et al of over 3500 burn injury patients treated at a US tertiary care burn center found that 18% of the study population’s burn cases were work related. The majority of work-related burn injuries occurred in young White males, with patients suffering from work-related burns tending to have fewer comorbidities, burns covering a smaller total body surface area, a lower inhalation injury risk, a shorter duration of intensive care treatment, and decreased hospitalization time, compared with patients whose burn injuries were not work related. In addition, work-related burns most often resulted from scalding, while the majority of non–work-related burns responsible for hospital admission were flame injuries. [2]

A study by Pusateri et al indicated that early fibrinolytic status impacts the mortality rate in patients with a thermal injury. Subjects in the study suffered the injury within 4 hours of presentation. An association was found between a hyperfibrinolytic (HF) phenotype at admission and increased 30-day mortality. However, no link was seen between a delayed HF phenotype and greater risk of death. The investigators also determined that while the presence of hypofibrinolytic/fibrinolytic shutdown (SD) at admission is not associated with a raised mortality rate, a delayed SD occurring at 4 hours or more post admission is linked to higher 30-day mortality, with the risk of death rising eight-fold at 4 hours. [3]

Evaluation of the Burn Patient

Before management of the burn wound can begin, properly and completely evaluate the burn patient. Often this is a brief effort, particularly in patients with small, uncomplicated wounds. In those with larger burns, evaluation of the wound often is of secondary importance. As described by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, evaluation of the burn patient is organized into a primary and secondary survey.

Primary survey

Burn patients should be systematically evaluated using the methodology of the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support Course. This evaluation is described by the primary survey, with its emphasis on support of the airway, gas exchange, and circulatory stability. First evaluate the airway; this is an area of particular importance in burn patients. Early recognition of impending airway compromise, followed by prompt intubation, can be life saving. Obtain appropriate vascular access and place monitoring devices, then complete a systematic trauma survey, including indicated radiographs and laboratory studies.

Secondary survey

Burn patients should then undergo a burn-specific secondary survey, which should include determination of the mechanism of injury, evaluation for the presence or absence of inhalation injury and carbon monoxide intoxication, examination for corneal burns, consideration of the possibility of abuse, and a detailed assessment of the burn wound. [4]

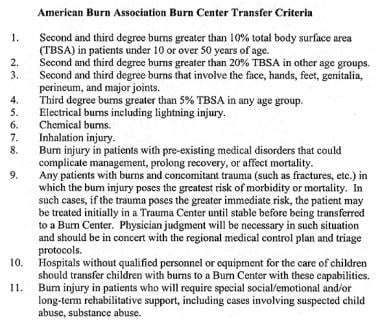

A detailed history must be elicited upon first evaluation and transmitted with the patient to the next level of care. Inhalation injury is diagnosed by a history of a closed-space exposure and soot in the nares and mouth. Carbon monoxide intoxication is suspected in those injured in structural fires, particularly if they are obtunded; carboxyhemoglobin levels can be misleading in those ventilated with oxygen. Those with facial burns should undergo a careful examination of the cornea prior to the development of lid swelling that can compromise examination. After evaluation of the burn wound, begin fluid resuscitation and make decisions concerning outpatient or inpatient management or transfer to a burn center (see the image below).

American Burn Association has developed a set of criteria for burn center transfer. These have been adopted by most emergency medical services.

American Burn Association has developed a set of criteria for burn center transfer. These have been adopted by most emergency medical services.

Guidelines

Guidelines released in 2020, from a panel of experts brought together by organizations that included the French Society of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Perioperative Medicine (SFAR), provided recommendations for the management of severe acute-phase thermal burns in adults and children. These included, but were not limited to, the following suggestions [5] :

-

In hemodynamic management, use balanced crystalloid solutions

-

In hemodynamic management, the formula used in estimating the initial crystalloid infusion rate should at least include the body weight and total burned body surface area (BSA)

-

Basing changes on clinical and hemodynamic parameters, adjust the infusion rate as soon as possible in fluid resuscitation for severe burns

-

Patients with severe burns in whom the total burned BSA is over 30% should receive human albumin after the first 6 hours of management

-

Do not routinely intubate patients with burns involving the face or neck

-

If burns involve the entire face, consider intubation if the patient also demonstrates at least one of the following features: 1) a deep, circular neck burn; 2) symptoms of airway obstruction (ie, change in voice, stridor, laryngeal dyspnea); 3) a total burned BSA of 40% or greater

-

Do not routinely administer hydroxocobalamin after smoke inhalation

-

Restrict hydroxocobalamin administration to adults suffering from smoke inhalation in whom there is a high suspicion of severe cyanide poisoning and to children with smoke inhalation and signs of moderate to severe cyanide poisoning

-

In the absence of shock, burn cooling should be performed in adults with a total burned BSA of less than 20% and in children with a total burned BSA of less than 10%

-

Routinely prescribe thromboprophylaxis for severe burn patients in the initial phase

Evaluation of the Burn Wound

After the patient has been fully evaluated and stable hemodynamics and gas exchange ensured, evaluate the burn wound in detail. Evaluate burn wounds initially for extent, depth, and circumferential components. Decisions regarding type of monitoring, wound care, hospitalization, or transfer are made based on this information.

Extent of burn

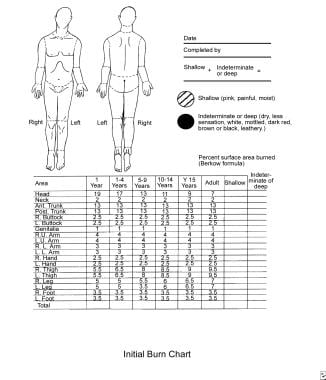

An accurate estimate of burn size is important for treatment and transfer decisions. Burn size or extent can be estimated in numerous ways. Perhaps most accurate is the age-specific chart based on the Lund-Browder diagram that compensates for the changes in body proportions with growth (see the image below).

A burn is drawn on a cartoon figure and an associated age-specific table is used to calculate the body surface area involved.

An alternative in adults is the Rule of Nines. This is less accurate in children because their body proportions are different than those of adults. For areas of irregular or nonconfluent area burns, the palmar surface of the patient's hand can be used. For a wide age range, the area of the palm without the fingers represents 0.5% of the body surface.

Burn depth

Burns are routinely underestimated in depth on initial examination. Devitalized tissue may appear viable for some time after injury, and often, some degree of progressive microvascular thrombosis around the periphery of wounds is seen. Consequently, the wound appearance changes over the days following injury. Serial examination of burn wounds can be very useful.

Burn depth is classified as first, second, third, or fourth degree.

First-degree burns usually are red, dry, and painful. Burns initially termed first degree often are actually superficial second degree, sloughing the next day.

Second-degree burns often are red, wet, and very painful. Their depth, ability to heal, and propensity to form hypertrophic scars varies enormously (see the image below).

Second-degree burns often are red, wet, and very painful. Their depth, ability to heal, and tendency to result in hypertrophic scar formation vary enormously.

Second-degree burns often are red, wet, and very painful. Their depth, ability to heal, and tendency to result in hypertrophic scar formation vary enormously.

Third-degree burns generally are leathery in consistency, dry, insensate, and waxy. These wounds will not heal, except by contraction and limited epithelial migration with resulting hypertrophic and unstable cover (see the image below).

Third-degree burns usually are leathery in consistency, dry, and insensate. These wounds will not heal.

Third-degree burns usually are leathery in consistency, dry, and insensate. These wounds will not heal.

Burn blisters (see the image below) can overlie both second-degree and third-degree burns.

Management of burn blisters is controversial. Burn blisters occasionally obscure the presence of full-thickness wounds.

Management of burn blisters is controversial. Burn blisters occasionally obscure the presence of full-thickness wounds.

The management of burn blisters remains controversial, yet intact blisters help greatly with pain control. Debride blisters if infection occurs.

Fourth-degree burns involve underlying subcutaneous tissue, tendon, or bone. Accurately determining burn depth on early examination is usually very difficult, even for an experienced examiner. As a general rule, burn depth is underestimated on initial examination.

Please also see Medscape Drugs & Diseases article Thermal Burns for further information on the depth of burn injury and its effect on the skin.

Note circumferential, or near circumferential, burn wounds because they may cause progressive extremity ischemia or interfere with ventilation as burn wound swelling increases. In such situations, timely escharotomy is essential. Perform extremity escharotomies as soon as peripheral perfusion is threatened. Do not wait until the extremity is overtly ischemic. Perform torso escharotomies as soon as ventilation appears compromised.

Burn Wound Infection

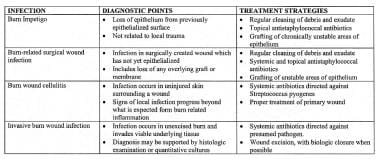

An ability to make the diagnosis of burn wound infection is important. A clinically focused set of burn wound infection definitions recently has been published (see the image below).

Two of these, burn wound cellulitis and invasive burn wound infection, are seen with some regularity by clinicians outside a burn center environment.

Burn wound cellulitis (see the image below) usually manifests as progressive erythema, swelling, and pain in the uninjured skin around a wound.

Burn wound cellulitis presents with increasing erythema, swelling, and pain in uninjured skin around the periphery of a wound.

Burn wound cellulitis presents with increasing erythema, swelling, and pain in uninjured skin around the periphery of a wound.

Usually, this is seen in the first few days after burning and typically is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infection can progress rapidly but is generally sensitive to penicillin. Excision of associated deep eschar can be essential to the successful treatment of cellulitis. Elevation to reduce edema is an important adjunct.

Invasive burn wound infection (see the image below) is a rapid proliferation of bacteria in burn eschar that proceeds to invade underlying viable tissues.

Invasive burn wound infection implies that bacteria or fungi are proliferating in eschar and invading underlying viable tissues. These wounds display a change in color, new drainage, and often a foul odor. These infections are life-threatening.

Invasive burn wound infection implies that bacteria or fungi are proliferating in eschar and invading underlying viable tissues. These wounds display a change in color, new drainage, and often a foul odor. These infections are life-threatening.

A change in color, new drainage, and, occasionally, a foul or sickly sweet odor are clinical findings. Pseudomonas and other gram-negative species are common causes. This infection can be life-threatening and usually requires combined treatment with surgery and antibiotics.

Fever and systemic toxicity commonly accompany both infections. Inspect burn wounds frequently to identify infection early. This is an important consideration in outpatient burn care. Someone must inspect the wounds managed in the outpatient environment to promptly detect infections. Errors in initial depth assessment are routine. Infections occur and must be treated in a timely way. A wound-monitoring plan is an essential part of burn care.

A study by Bache et al documented the dispersal of bacteria into the air from burn wounds during dressing and bed sheet changes, a phenomenon that may increase the risk of nosocomial cross-contamination in hospital burn units. The study involved three patients with total burn surface areas of 35-51%. The investigators found that the level of airborne bacteria not only increased in each patient’s room when dressings and bed sheets were changed, but that the level (up to 2614 cfu/m3) remained elevated for about 1 hour after the changing. According to the study, the increases were not affected by whether the dressing was changed before the bed sheet or vice versa. [6]

A retrospective study by Fochtmann-Frana et al indicated that in patients with burn injuries, the presence of a higher Abbreviated Burn Severity Index score and total burn surface area, as well as the need for fasciotomy, raises the likelihood of bloodstream infection with Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, and Candida. [7]

Burn Wound Management

Most burns are small; patients with small burns are appropriately managed as outpatients if their burns do not involve critical areas such as the face, hands, genitals, or feet. The outpatient setting is the primary focus of this section. Outpatient burn management can be taxing and, when poorly performed, can cause unnecessary suffering and compromise long-term results. In some situations, coordinating outpatient management with the burn unit's team of doctors, nurses, and therapists is helpful, as their expertise may facilitate attaining optimal outpatient results; however, most small burns are well managed by community based providers with burn center consultation as needed.

Selection for outpatient care

Several factors are relevant to a decision regarding the location of burn care. The patient's airway must not be potentially compromised. The wound must be small enough so that fluid resuscitation is unnecessary (this generally precludes outpatient care of burns over 10-15% of body surface). Patient must be able to take in adequate fluid orally. Typically, serious burns of the face, ears, hands, genitals, or feet should be initially managed on an inpatient basis.

The patient and his or her family must be able to support an outpatient care plan. A child managed as an outpatient must have an adult caregiver available. A family member or visiting nurse must be available who can perform the necessary wound cleansing, inspection, and dressing applications, as most patients cannot do this themselves. Family must have adequate transportation to return for clinic visits and unexpected emergency visits. If abuse is suspected, outpatient management is contraindicated. Finally, if, on initial examination, surgery is clearly needed for a full-thickness wound area, the patient should be admitted for surgery promptly. Despite all of these qualifications, most patients with smaller burns can be successfully managed as outpatients.

Outpatient wound care strategies

Components of outpatient burn care include the following:

-

Patient and family education

-

Wound cleansing

-

Choice of topical or membrane dressing

-

Pain control

-

Early return instructions

-

Follow-up clinic visits

-

Long-term follow-up care

Wound cleansing and dressing techniques must be taught to the person who changes the dressings. Documenting this teaching is ideal.

Which of many medications or membranes to place on burn wounds remains unclear, but certain basic principles apply to all situations. Gently clean the wound of debris and exudate on a regular basis. This usually requires daily removal of accumulated exudate and topical medications. Small superficial burns managed in this setting present a low risk of infection, thus a clean rather than sterile technique is reasonable. Patients may clean the burn with lukewarm tap water and mild soap.

Soaking dressings in lukewarm tap water may decrease the pain associated with their removal. Gently cleanse the wound with a gauze or clean washcloth, inspect for signs of infection, pat dry with a clean towel, and re-dress the patient. To manage infections promptly, it is important to teach the patient and family to return promptly if they notice erythema, swelling, increased tenderness, odor, or drainage. Frequency of wound cleansing and dressing change is debated, but most small burns are managed adequately with daily cleansing and dressing.

Wound dressing, whether one is using topical medication or a wound membrane, should provide 4 benefits: (1) prevention of wound desiccation, (2) control of pain, (3) reduction of wound colonization and infection, and (4) prevention of added trauma to the wound. Most topicals in outpatient use have a viscous carrier that prevents wound desiccation and a broader antibacterial spectrum that reduces wound colonization. Addition of a gauze wrap minimizes soiling of both clothing and unburned skin and protects the wound from the external environment. A large number of excellent agents are available.

Superficial facial burns are commonly treated with a clear, viscous antibacterial ointment. Wounds around the eyes can be treated with heavy topical ophthalmic antibiotic ointments. For more information, see Medscape Drugs & Diseases article Ocular Burns. Treat deep burns of the external ear with mafenide acetate, as it penetrates the eschar and prevents purulent infection of the cartilage. Appropriate wound care strategies address these principles.

Control of pain in the outpatient setting can be difficult, and if pain and anxiety cannot be adequately managed at home, then hospitalization is appropriate. In most patients, an oral narcotic medication administered 30-60 minutes prior to a planned dressing change provides adequate pain control. As most dressings are occlusive, pain control between dressing changes tends to be managed adequately without narcotics in most patients.

Elaborate specific conditions mandating an early return. Particularly important are (1) pain and anxiety associated with wound care to the degree that wound care is compromised, (2) signs of infection, or (3) a wound that appears deeper than appreciated at initial examination. Review wound care instructions with caregivers.

Inpatient management

The plan of management of patients with large burns that require inpatient care usually is determined by the physiology of burn injury. Management strategies for these patients are beyond the scope of this article but generally require a coordinated approach that involves a specialized team. Hospitalization is divided into 4 general phases: (1) initial evaluation and resuscitation, (2) initial wound excision and biologic closure, (3) definitive wound closure, and (4) rehabilitation and reconstruction.

Medications and Membranes

The choice of which medication or membrane to place on a wound is a neverending source of discussion and argument. Fortunately, most medications and membranes perform well if physicians carefully monitor wounds, keep them clean, prevent desiccation, and properly manage secondary infection.

A wide range of topical medications is available, including simple petrolatum, various antibiotic-containing ointments and aqueous solutions, and debriding enzymes. Some of the available topical medications and their characteristics are listed in the tables below.

Medications (Open Table in a new window)

| Medication | Important Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Silver sulfadiazine | Broad antibacterial spectrum; painless on application |

| Silver nitrate | Broad spectrum, including fungi; will leach electrolytes |

| Mafenide | Broad antibacterial spectrum; penetrates eschar best |

| Petrolatum topical | Bland and nontoxic; useful for protecting skin surrounding eschar removal |

| Anacaulase | Gel mixture of proteolytic enzymes that are taken from pineapple plant (Ananas comosus) stems; used for eschar removal |

| Various debriding enzymes | Useful in selected partial-thickness wounds |

| Various antibiotic ointments | Useful in many superficial or partial-thickness wounds |

Membranes (Open Table in a new window)

| Membrane | Important Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Porcine xenograft | Adheres to wound coagulum and provides excellent pain control |

| Split-thickness allograft | Vascularizes and provides durable temporary closure of wounds |

| Various hydrocolloid dressings | Provide vapor and bacterial barrier while absorbing wound exudate |

| Various impregnated gauzes | Provide vapor and bacterial barrier while allowing drainage |

| Various semipermeable membranes | Provide vapor and bacterial barrier |

| Acticoat (Westhaim Biomedical; Saskatchewan, Canada) | Nonadherent wound dressing that delivers low concentration of silver for antisepsis |

| Biobrane (Dow-Hickham; Sugarland, TX) | Synthetic bilaminate that facilitates fibrovascular tissue growth into inner layer and provides temporary vapor and bacterial barrer |

| Transcyte (Smith and Nephew; Largo, FL) | Synthetic bilaminate that facilitates fibrovascular tissue growth into inner layer that is populated with allogenic fibroblasts and overlying layer that provides temporary vapor and bacterial barrier |

| AlloDerm (LifeCell; The Woodlands, TX) | Consists of cell-free, allogenic human dermis that requires immediate thin overlying autograft |

| Integra (Integra LifeSciences Corp; Plainsboro, NJ) | Provides scaffold for neodermis that requires delayed thin autograft |

All of the above agents can be effective when properly used by experienced providers in a program of burn care that includes wound evaluation, regular cleansing, and monitoring.

Wound membranes are different from medications and dressings in that they provide transient physiologic wound closure. This implies a degree of protection from mechanical trauma, vapor transmission characteristics similar to skin, and a physical barrier to bacteria. These membranes facilitate a moist wound environment with low bacterial density. They are commonly placed on clean superficial wounds while awaiting epithelialization. These membranes are mostly occlusive; therefore, they must be used with caution if wounds are not clearly clean and superficial. If an occlusive membrane is placed over devitalized tissue, submembrane purulence can occur with subsequent local and systemic sepsis. A large number of these membranes are available.

A literature review by Fang et al indicated that the frequency of employment of a combination of acellular dermal matrices with cultured epidermal autografts is increasing in patients with extensive deep dermal or full-thickness burn injuries. This treatment can be used in patients whose burn wounds cover too much surface area to permit split-thickness skin grafting. [8]

Wounds in Special Areas

Face, ears, hands, genitals, and feet have functional and cosmetic significance that far exceeds their size and physiologic importance. The surface area involved is such that burn sepsis from these sources rarely is life-threatening, and a studied approach to these wounds usually is possible.

Face

Especially in adolescents and adults, the deep sweat and sebaceous glands of the central face make it likely that most second-degree burns will heal well with adequate topical wound care. Many reasonable management options are available, including topical silver sulfadiazine or bland antibiotic ointments. Burns around the eyes can be dressed with topical ophthalmic antibiotic ointments. If grafting is a possibility, reserve thick donor skin with optimal color match for facial resurfacing. Often, the "blush" areas, such as the upper back and shoulders, make good facial donor sites. [9, 10, 11]

The most important point of early management of deeply burned ears is prevention of auricular chondritis. This is a serious complication in which the cartilage becomes infected and quickly liquefies. Twice daily cleansing and application of topical mafenide acetate, which penetrates the eschar, can minimize the condition. Subsequent management of the ear is based on depth of injury.

Deep corneal burns are obvious on physical examination. The cornea has a clouded appearance. More subtle injuries can be detected only with topical fluorescein application. After facial edema resolves, lid retraction may occur with variable degrees of exposure of the globe or ectropion. When this is relatively mild, no intervention is required beyond ocular lubricants. Should keratitis occur, early lid release is advised.

Hand burns

Hand burns assume a high priority from the onset of care. During the first 24-48 hours, adequate blood flow must be ensured. Regularly monitor consistency, temperature, and the presence of pulsatile flow detectable by Doppler in the digital pulp. If blood flow is questionable, perform escharotomy or fasciotomy.

Splint hands in a position of function: the metatarsophalangeal joints at 70-90 º, interphalangeal joints in extension, first web space open, and wrist at 20 º of extension. Elevate hands to minimize edema and have the patient perform range-of-motion exercises with a therapist twice daily. Deep dermal and full-thickness burns should undergo early excision and sheet autograft closure. Perform hand therapy throughout the healing period, halting only in the few days immediately after grafting. If this is not done, suboptimal long-term function results (see the image below).

Conclusions

After making a careful initial evaluation, refer patients with complex, deeper, or larger wounds for specialty care. In others, application of basic principles of management combined with regular monitoring constitutes adequate therapy and leads to routinely good results.

A retrospective study by Nagpal et al of pediatric patients with burns over 15% or more of their total body surface area found an independent association between persistent cumulative fluid overload on day three following injury and beyond and the development of adverse outcomes, including longer stay in the pediatric intensive care unit and longer duration of mechanical ventilation. [12]

-

American Burn Association has developed a set of criteria for burn center transfer. These have been adopted by most emergency medical services.

-

Burn size is best estimated using a chart that corrects for changes in body proportion with aging.

-

Second-degree burns often are red, wet, and very painful. Their depth, ability to heal, and tendency to result in hypertrophic scar formation vary enormously.

-

Third-degree burns usually are leathery in consistency, dry, and insensate. These wounds will not heal.

-

Management of burn blisters is controversial. Burn blisters occasionally obscure the presence of full-thickness wounds.

-

This clinically focused definition set describes burn wound infections.

-

Burn wound cellulitis presents with increasing erythema, swelling, and pain in uninjured skin around the periphery of a wound.

-

Invasive burn wound infection implies that bacteria or fungi are proliferating in eschar and invading underlying viable tissues. These wounds display a change in color, new drainage, and often a foul odor. These infections are life-threatening.

-

If hand positioning and therapy are ignored while overlying burns heal, poor long-term function may result.

-

Second-degree burns are often red, wet, and very painful. An enormous variability exists in their depth, their ability to heal, and their tendency to result in hypertrophic scar formation.

-

2-year-old child is brought to office for evaluation of scald burn to hand.

-

Splinting of serious hand burn.