Background

The treatment of the aging periorbita is arguably one of the most powerful rejuvenating facial procedures, with the capability of restoring a freshened, more youthful appearance. [1] The eyes, more specifically, the periorbital tissues are vital in the expression of emotion but also are telling of age, gender, and beauty. Unfortunately, the delicate nature of these intricate structures is susceptible to the effects of ultraviolet light exposure, gravity, and repetitive animation.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, its members performed 115,261 blepharoplasties in 2022, a 13% increase from 2019, before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. [2]

The variety of surgical and nonsurgical approaches for rejuvenation of the periorbita necessitates keen knowledge of the pertinent anatomy, clinical judgment in the application of these techniques and experience to avoid potential complications. Multiple surgical techniques have been described to address both the upper and lower eyelids, however, the operative goals are universal. When addressing the lower eyelid, the surgeon’s aims are to eliminate redundant skin, smooth the underlying musculature, tighten the supporting structures if needed, and to resect or redrape excess retroseptal fat to smooth the transition from the lower eyelid to the cheek.

Transcutaneous lower lid blepharoplasty utilizes a subciliary skin incision coupled with adjunctive surgical maneuvers to accomplish these goals. Although this is a powerful procedure for patients seeking periorbital rejuvenation, it must be tailored to the individual to address their anatomical problems. [3]

History of the Procedure

The history of blepharoplasty dates back to more than 2000 years ago when Susruta described eyelid surgery in the Susruta-tantra. [4] Arabian surgeons later in the 10th century cauterized redundant eyelid tissues to restore a more youthful appearance. [5] Ambrose Pare described functional upper blepharoplasty for visual obstruction in the 16th century. [6] In the early 19th century, several aurthors described the resection of excess upper eyelid skin; however, it was Von Graefe in 1818 who coined the term blepharoplasty to describe eyelid surgery. [7, 8, 9] Expanding upon Sichel’s description of herniated retroseptal fat, Bourget described the separate compartments in the eyelids and the transconjunctival approach for excision of lower lid fat. [10, 11, 12]

Based upon these previous contributions, Costañares precisely detailed the anatomy of the eyelid fat compartments, describing what may be considered the modern blepharoplasty. [11] Costañares’ contemporary, Sir Archibald McIndoe was the first to perform a transcutaneous approach to the retroseptal fat utilizing a skin-muscle flap. This technique gained popularity because of the ease of dissection, increasing the margin of safety for the procedure.

In the 1970s, Furnas further characterized the components of the aging lower lid, recognizing the contribution of redundant orbicularis oculi muscle. [13] While prior techniques focused upon resection to restore a more youthful appearance, Loeb recognized that fat preservation and translocation rather than resection, was effective for blending the transition between the lower eyelid and cheek. [14] Hamra championed the cause of fat preservation and expanded the concept with complete release of the arcus marginalis with fat translocation to soften the lid-cheek junction. [15]

The increasing popularity of aesthetic surgery and adjunctive non-surgical options lead to changes in the approach to periorbital rejuvenation in the 1990’s. Surgeons coupled laser and chemical skin resurfacing techniques with transconjunctival lower lid blepharoplasty, touting the efficacy of the technique and its lowered complication rates compared with other techniques. [16] The proponents of this approach espoused that the surgical manipulation of the orbicularis oculi in transcutaneous techniques lead to its denervation, and secondarily to lower eyelid malposition although these claim were not substantiated in comparative studies. [17, 18, 19] Unfortunately, aggressive rejuvenation procedures incorporating surgical and nonsurgical techniques lead to increasing morbidity with a rise in lower lid malposition and ectropion.

Combining multiple surgical approaches such as using transconjunctival incisions for orbital fat access and preservation paired with a skin-only excision has garnered attention. [20] This technique achieves blending of the lid-cheek junction through re-draping and suspension of orbital fat while avoiding denervation of the orbicularis muscle. More conservative skin removal or “pinch” technique and lateral tightening may reduce lower lid malposition and changes to the eye aperture. [21]

Moreover, the use of autologous fat injection or hyaluronic fillers to restore volume to the periorbita may be applicable in more difficult cases not amenable to traditional eyelid procedures as a result of soft tissue atrophy. [22, 23] However, complications such as blindness, skin necrosis, and contour irregularities have been reported, necessitating further evaluation of outcomes and refinements in technique. [24, 25]

Huang et al described a modified transcutaneous lower lid blepharoplasty technique in which a subciliary elliptical skin excision is made; the medial, middle, and lateral orbital fat compartments are resected; and microautologous fat transplantation (MAFT, using a MAFT-GUN) is used to recontour prominent nasojugal and palpebromalar grooves. [26]

The recognition of patients who are morphologically susceptible to lower lid malposition has led to an emphasis on lateral canthal support as an adjunctive procedure. Lateral canthopexy and canthoplasty are now commonly incorporated maneuvers in lower lid blepharoplasty to aid in the prevention of lower lid malposition. [27, 28, 29] As more interest arises in periorbital rejuvenation, the surgeon will be required to consider not only the medical and anatomic variations in their patients but also the psychological well being of those being selected for an operative intervention.

Presentation

Preoperative assessment

A prerequisite to the planning and the technical execution of any operation is the implicit comprehension of the patient's concerns. Once the patient and the surgeon have a mutual understanding, a comprehensive plan can be constructed, incorporating the patient’s wishes, their underlying anatomical issues, the surgeon’s observations of the problem and the limitations of the procedure. The consultation should first focus upon the patient’s global medical and surgical history, eliciting any issues that may exclude or increase the morbidity of the surgical plan. Chronic medical conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hepatic disease, thyroid disease and bleeding diatheses should be elicited. A more focused surgical and medical history should be obtained, focusing on prior eye surgery such as photorefractive keratectomy and underlying ophthalmologic conditions such as blepharochalasis.

Subsequent to the patient’s history, a comprehensive review of systems should be conducted, specifically querying the patient about excessive tearing, dryness, frequent blinking, redness and burning of the eyes, and contact lens use.

Of the previously mentioned symptoms, dryness of the eyes deserves special attention. It can have multiple causes including insufficient tear production and excessive tear evaporation. Complaints may include itchy eyes, foreign body sensation, blurry vision, pain, and ocular fatigue. In the general population, 12% of men and 17% of women experience symptoms of dry eyes. [30] If one suspects a patient may have dry eye syndrome or any other ocular complaints, a referral to an ophthalmologist is appropriate.

There are many risk factors for dry eye including environmental, pharmacologic, and systemic illness, however it is important as the surgeon to identify anatomical risk factors on physical examination and to then plan accordingly. A history of previous ophthalmologic surgery such as LASIK, cataract procedures or even prior blepharoplasty also increases the risk for dry eye. [31] Briefly, the Schirmer test has not been shown to be a reliable predictor of patients at risk for dry eye, but rather a detailed history and focused physical examination is a more useful tool. [32]

Chronic allergies, tobacco, alcohol use and current medications including herbal supplements should also be noted. Specifically, aspirin and the use of other anticoagulation medications should be documented. The underlying condition necessitating the use of these medications must be also discerned and the decision made whether withholding these medications is safe for the patient. Bleeding complications can lead to serious morbidity compounded upon the fact that blepharoplasty is an elective surgery. It is our practice to have the patient discontinue aspirin and anti-platelet agents two weeks prior to surgery and for one week afterward if their medical condition will allow this lapse in therapy.

Physical

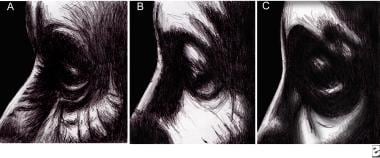

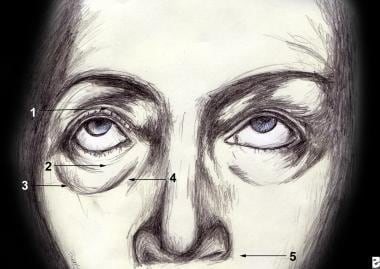

The physical examination should catalogue the anatomical structures that comprise the lower lid as well as the surrounding periorbital architecture as it pertains to the patient’s concerns. Carefully note the surface anatomy of the periorbital region (see the image below). This survey should also note any anatomical variants that may predispose to postoperative morbidity.

Topographic anatomy of the eyelid. 1.Superior tarsal fold 2.Inferior tarsal fold 3.Palpebromalar groove 4.Nasojugal groove 5.Nasolabial fold. Adapted from Jelks, 1993.

Topographic anatomy of the eyelid. 1.Superior tarsal fold 2.Inferior tarsal fold 3.Palpebromalar groove 4.Nasojugal groove 5.Nasolabial fold. Adapted from Jelks, 1993.

In order to devise a comprehensive operative plan to treat the patient’s concerns, the surgeon must have an astute understanding of facial and periorbital aging. The youthful face is grossly characterized by elastic skin without dyspigmentation, well-supported fat and smooth transitions between aesthetic subunits.

In contrast, superficial evidence of aging in the lower periorbita includes changes secondary to actinic damage such as varying degrees of rhytids, the development of keratoses and dyschromias. In general, there is not an over-abundance of excess lower eyelid skin and over-resection can lead to lid malposition.

The supporting structures of the lower lid also succumb to age and gravity, as the tarsus and the canthal ligaments become less elastic causing increased scleral show and lid displacement. The orbicularis oculi and the septum orbitale also become more lax and redundant, permitting the formation of festoons and the pseudoherniation of the orbital fat. To demonstrate this laxity, the lid snap-back test should be performed to ascertain the need for lid support. A positive test is confirmed when one second or more has elapsed before the lid returns to its resting position on the eye after being maximally distracted anteriorly.

Quantitative measures that are clinically significant for lower lid laxity include intraoperative lid distraction of greater than 3 mm of over the lateral orbital rim or 6 mm of anterior distraction away from the globe. [33] If lower eyelid laxity is confirmed upon examination, an adjunctive procedure should be incorporated into the operative plan to provide lower eyelid support.

The surrounding architecture of the periorbita is equally important in determining the indication for lower eyelid support. Notably, the relationship between the anterior projection of the globe, lower lid, and malar eminence, as described by Jelks and Jelks, is a key element in the preoperative evaluation (see the image below). [34] The patient with a negative vector relationship is predictably, morphogenically prone to postoperative lower lid malposition. This relationship exists when the most anterior projecting point on the globe lies anterior to the inferior orbital rim. Thus, a negative vector relationship is an indication to include operative maneuvers for lower eyelid support.

The patient with a prominent globe is also morphogenically prone to lower lid malposition postoperatively unless it is recognized preoperatively and addressed intraoperatively. [35] Similar to the assessment of the negative vector relationship, globe prominence is determined by evaluating the position of the globe relative to the orbit. Multiple systems are available, however the Hertel exophthalmometer is most commonly used. It measures the distance between the most anterior projecting point of the globe and the lateral orbital rim. Although ethnic differences exist, globe projection between 15 to 17mm is considered within normal limits. [36] In cases where globe projection is greater than 18mm, special considerations and surgical maneuvers are necessary when addressing the lateral canthus to avoid lower lid malposition, scleral show and ultimately dry eye syndrome. Hirmand et al., provides an excellent description of the management of these challenging cases. [37]

Amongst other important factors to assess is the relative paucity or excess of retroseptal fat. With the patient in an erect position, the quantity of retroseptal fat can be observed, coupled with gentle ballotment of the globe to determine which compartments contain excess fat. While a paucity of fat will exclude fat excision from the operative plan, excess fat can be excised or repositioned to smooth the transition of the lid cheek junction.

A limited ophthalmologic exam should also be performed including visual acuity, evaluation for visual field deficits and extraocular motor function. If any significant deficits exist, the patient should be referred for ophthalmologic evaluation.

Finally, a photographic record should also be established documenting the preoperative periorbital anatomy. We recommend acquiring an anterior and lateral full-face view along with close-up views of the periorbital area with the eyes in neutral and upward gaze. Not only are these photographs an important part of the medical record, but they can facilitate a discussion about the patient’s anatomical problems and what can be realistically addressed.

Indications

Before a patient may be considered a candidate for lower lid blepharoplasty, a thorough preoperative history and physical examination should be obtained. A patient’s appropriateness for surgery should also include the feasibility of achieving their goals and meeting their expectations regarding the surgical outcome. In a sequential fashion, lower lid blepharoplasty can successfully address redundant skin and muscle, laxity of the septum, excess fat, lower lid malposition and prominence of the nasojugal groove. Problems related to exophthalmos, blepharochalasis and eyelid dyschromias are not surgically correctable with lower lid blepharoplasty and thus are not surgical indications for this procedure.

Relevant Anatomy

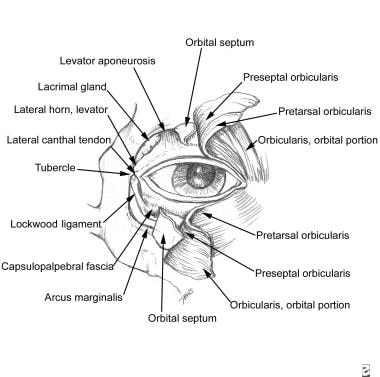

Detailed descriptions of the anatomy and innervation (see the image below) of the lower eyelid is described in numerous articles and texts. [19, 27, 29, 37, 38]

Anatomic topography

The lower lid margin commonly rests 1-2 mm above the inferior border of the limbus, making a gentle S curve. This border represents the lower half of the palpebral fissure. When the lower lid rests below the limbus, the patient exhibits scleral show.

Skin

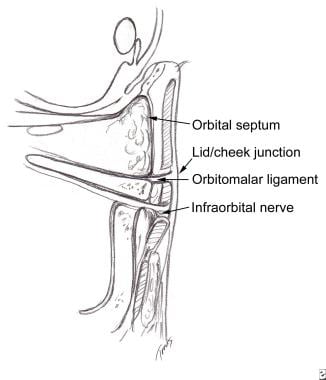

The delicate skin of the lower eyelid is closely adherent to the underlying tarsus superiorly, becoming thicker in quality over the more caudad preseptal region. The youthful lower eyelid has a smooth transition into the malar eminences. A hallmark of periorbital aging is an abrupt transition between the lower eyelid and cheek, defined by the radial expansion above and below the orbitomalar ligament (see the image below). [37]

Muscle

The orbicularis oculi muscle is closely adherent to the overlying periorbital skin and is designated into three zones: the pretarsal, preseptal, and orbital regions. The preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle splays into two heads. The anterior head coalesces into the anterior crus of the medial canthal tendon, which inserts on the frontal process of the maxilla. The posterior head inserts dorsally onto the posterior lacrimal crest. The orbicularis muscle is segmentally innervated primarily by the zygomatic distribution of the facial nerve laterally and secondarily by the buccal branches medially.

Septum/fat

The orbital septum is a fibrous membrane that confines the intraorbital fat to the orbit. The arcus marginalis is the insertion of the orbital septum onto the osseous orbital rim. The retroseptal fat is divided into the medial, central and lateral fat compartments. The medial and central fat compartments are separated by the inferior oblique muscle, which can be injured during transcutaneous fat excision secondary to its anatomic location. [39] The lateral fat compartment is frequently under-resected in aesthetic lower lid blepharoplasty and can be approached from either a lower or upper lid approach, depending upon the patient’s anatomic concerns.

Lateral Canthal Tendon

The lateral canthal tendon (LCT) has been a controversial area of periorbital anatomy; however, reports of cadaveric dissections in the literature have attempted to clarify its nature. [40, 41] The LCT attaches the tarsal plate to the orbital rim via a fascial support system and can be separated into a superficial and deep component. The LCT is bordered anteriorly by adipose tissue (Eisler’s pocket) and posteriorly by the check ligament of the lateral rectus muscle. The term “tendon-ligament” has been used to describe the anatomic connections between the tarsal plate and the pretarsal orbicularis oculi muscle medially to the orbital tubercle laterally, which provides structural fixation of both the upper and lower lids. The LCT also allows for mobility of the lateral canthal angle by its posterior fibrous attachments to the check ligament of the lateral rectus muscle, which is evident upon extreme lateral gaze. It is this structure that must be addressed topreventlowereyelid malposition and sequelae when the patient presents with underlying lower lid laxity, a negative vector relationship or a prominent eye.

Contraindications

Patient selection is of paramount importance when deciding who is an appropriate candidate for any elective aesthetic procedure. Conditions that would preclude a patient from undergoing periorbital rejuvenation include patients with unrealistic expectations and/or significant medical comorbidities. Specifically, patients with underlying endocrinological or conditions such as dry eye syndrome should be carefully evaluated. An ophthalmologic evaluation should be strongly considered if these patients are being considered for periorbital rejuvenation.

-

Topographic anatomy of the eyelid. 1.Superior tarsal fold 2.Inferior tarsal fold 3.Palpebromalar groove 4.Nasojugal groove 5.Nasolabial fold. Adapted from Jelks, 1993.

-

A. Positive vector B. Neutral vector C. Negative vector relationships between the globe and orbit.

-

Anatomy of the periorbital region.

-

Cross sectional anatomy of the lid-cheek junction.

-

Subciliary incision design as reported by Rees and Dupuis.

-

Technique of skin-muscle flap elevation from Rees and Dupuis.

-

Depiction of retroseptal fat compartments and fat resection.

-

Huang's technique for plication of the septum.

-

Hamra's lateral orbicularis suspension.

-

Fagien's simplified lateral canthopexy.

-

Fagien's lateral canthoplasty.

-

Skin excision and closure.