Overview

The congenital nevomelanocytic nevus (CNN), known commonly as the congenital hairy nevus, denotes a pigmented surface lesion present at birth (see image below). [1, 2] Surgical excision with reconstruction is the mainstay of treatment.

Congenital nevomelanocytic nevus of the abdomen with a pebbled surface. Courtesy of Patricia K. Gomuwka, MD.

Congenital nevomelanocytic nevus of the abdomen with a pebbled surface. Courtesy of Patricia K. Gomuwka, MD.

Nevomelanocytes, derivatives of melanoblasts, compose the cellular format of the neoplasm. [3]

Multiple definitions have been used to classify nevi into small, medium, or giant. These include diameter size, total body surface area (TBSA), and ability to excise in one surgical setting. [4]

Based on diameter, CNN are characterized as small (< 1.5 cm), medium (1.5-19.5 cm), and large or giant (>20 cm in adolescents and adults or predicted to reach 20 cm by adulthood). [5, 6]

Using the prediction classification, giant nevi have also been described as comprising 9 cm on a child’s head and 6 cm on a child’s body. [7]

The potential for large congenital nevi to become malignant is significant and is an important consideration in the treatment and management of this entity.

Malignancy

Multiple studies have attempted to elucidate the cumulative risk of developing cutaneous melanoma in patients born with CNN. [8]

A study at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center reported a 5.7% cumulative 5-year risk of developing a cutaneous melanoma in patients with large or giant CNN. [9]

A study of the Dutch nationwide pathology database reported a standardized incidence rate of 12.2% of developing melanoma in CNN. This study observed an increased risk of melanoma (in patients with CNN) of 6.4% for men and 14.1% for women when compared to general population rates. Furthermore, patients with giant CNN had an increased risk of 51.6% compared to general population rates. [10]

For small CNN, risk rates have been reported between 0.8% and 4.9%.

Very large congenital nevi account for less than 0.1% of cutaneous melanomas, whereas small varieties of congenital nevi may account for 15% of cutaneous melanomas.

Malignancy should be suspected with focal growth, pain, bleeding, ulceration, significant pigmentary change, or pruritus.

Management

Management and treatment of patients with CNN depends on the lesion’s size, location, and propensity for malignant transformation. Aesthetic considerations are important. Surgical treatment of giant or large CNN is addressed at age 6 months. [7, 11, 12]

Procedures used in surgical treatment include serial excision [13] and reconstruction with skin grafting, tissue expansion, local rotation flaps, and free tissue transfer. [14]

Adjunctive treatment options include chemical peels, dermabrasion, and laser surgeries. For more information, visit Medscape’s Aesthetic Medicine Resource Center.

Surgical excision remains the mainstay of treatment, since other adjunctive treatment options do not fully eradicate the nevus cells.

Cultured epidermal autographs have been used successfully in select cases. [15]

Management of small lesions includes close monitoring with photographic documentation versus surgical excision.

Incidence

CNN are present at birth or soon thereafter. The melanin pigment in the surface is apparent. Delay in appearance of surface pigmentation may occur from age 1 month to 2 years in the rare "tardive" type.

A CNN larger than 9.9 cm in diameter occurs in 1 per 20,000 newborns; a CNN larger than 20 cm in diameter occurs in 1 per 500,000 newborns. [16, 17]

The incidence for small nevi is 1 in 100 births; for medium nevi, 6 in 1000 births; and for large nevi, 1 in 20,000 births. [18]

Autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance or multifactorial determination occurs in families with small CNN.

CNN appear in all races, but, paradoxically, the frequency of small CNN is slightly higher in some populations such as blacks, who are at lower risk of developing melanoma than whites. [19] An equal prevalence of CNN exists in males and females.

Embryology

Melanoblasts migrate from the neural crest between weeks 8 and 10 of gestation. [20]

CNN develop in utero after the melanocytes appear but before the sixth antenatal month. [20] Supporting evidence for this timing is the documentation of the occurrence of the congenital divided nevomelanocytic nevus of the upper and lower eyelid.

The eyelid forms the fifth to sixth week in utero and fuses in the eighth to ninth week to reopen during the sixth month. [3]

Clinical Presentation

History

See the list below:

-

The presence of a pigmented lesion is noted at birth or soon thereafter.

-

Location and size of a congenital hairy nevus are variable.

Small lesions appear more frequently than large lesions.

Only 5% of lesions are multiple.

Coarse surface hairs (seen in the image below) develop in more than 50% of lesions and may occur during the first 1-2 years of life.

Physical examination

See the list below:

-

Size (in diameter)

Small (< 1.5 cm)

Medium (1.5-20 cm)

Large (>20 cm)

-

Borders

Sharp

Regular

Irregular

Blended with surrounding skin

-

Surface

Textured

With and without hair

-

Shape

Round

Oval

-

Color

Light brown

Dark brown

Halo (rare)

-

Location – Any site

-

Distribution

Single lesion

Multiple lesions (< 5% are multiple)

-

Associated findings

Neurofibromatosis

Leptomeningeal melanocytosis

Pathology

See the list below:

-

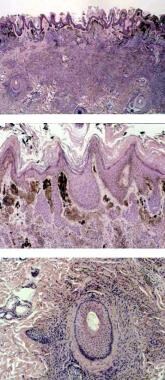

CNN have nevomelanocytes in the epidermis as well-ordered thèques or clusters and in the dermis as sheets, nests, or cords.

-

The presence of nevomelanocytes in the lower one third of the reticular dermis is specific for CNN. The nevomelanocytes may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. [21]

The images below depict the microscopic findings of a specimen from a patient with CNN.

Microscopic examination of specimen from the patient with an abdominal wall congenital nevomelanocytic nevus demonstrates confluence of dermal nevus cell nests and tracking along hair follicles. Courtesy of Carolyn F. Greeley, MD.

Microscopic examination of specimen from the patient with an abdominal wall congenital nevomelanocytic nevus demonstrates confluence of dermal nevus cell nests and tracking along hair follicles. Courtesy of Carolyn F. Greeley, MD.

A study by Salgado et al suggested that patients with large/giant CNN also have a higher density of mast cells in their skin, both in normal-appearing areas and in the nevi, than do individuals without such nevi. The investigators pointed out that the same stem cell factor that regulates/activates nevocytes is also involved in the differentiation/proliferation of mast cells and suggested that the higher density of mast cells may be related to wound-healing abnormalities and allergic reactions reported in patients with large/giant CNN. [23]

A retrospective study by Simons et al looking at atypical histopathologic characteristics of CNN in pediatric patients found, with regard to prevalence, that out of 197 CNN (179 patients, aged 0-35 months), 73% demonstrated cytologic atypia, architectural disorder, or pagetoid spread. However, over a mean follow-up time of 7.3 years, neither melanoma nor CNN-associated mortality occurred among the subjects. The investigators cautioned that the report used a predominately Caucasian population and that darker-skinned children might demonstrate different results. [24]

Differential Diagnosis

Acquired nevomelanocytic nevus: This is a common mole. It is a collection of nevomelanocytes in the epidermis (junctional), in the dermis (intradermal), or in both areas (compound). [3]

Becker nevus: This large unilateral lesion is usually seen on the shoulder of males and consists of a sharply but irregularly demarcated area demonstrating hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis. [3] Click here for more information and for images.

Café-au-lait macules: These flat, light brown surface lesions are associated with neurofibromas. [3] Click here to view an image of Café-au-lait macules.

Congenital blue nevus: This lesion is a small, well circumscribed, dome-shaped nodule of slate blue or bluish-black color. [3] See Medscape Reference article Blue Nevi for more information and for images.

Dysplastic melanocytic nevi: [3] A high incidence of melanoma is observed in patients with dysplastic melanocytic nevi. Since removing all the pigmented lesions in these patients is impractical, lesions demonstrating recent changes in color and appearance are removed.

Lentigo: This condition occurs in areas exposed to the sun and possesses a uniform dark-brown color and an irregular outline. [3]

Mongolian spots: These lesions typically occur in the lumbosacral region as a bluish discoloration resembling a bruise. [3] Click here to view images of Mongolian spots.

Nevus sebaceous: [3] This lesion is usually located on the scalp or on the face as a single lesion and is present at birth. A nevus sebaceous is a circumscribed, slightly elevated hairless plaque, typically not pigmented like a CNN. In puberty, the lesion becomes verrucous and nodular and may show areas of linear distribution. See Medscape Reference article Nevus Sebaceous for more information and for images of this lesion.

Nevus spilus: A nevus spilus is a light brown patch or band that is present since birth. In childhood, it becomes dotted with small dark brown macules. [3] Click here to view an image of nevus spilus.

Pigmented epidermal nevi: This condition is characterized by a persistent linear, pruritic lesion composed of red, scaling, verrucous papules arranged in one or several lines. [3] Click here to view an image of pigmented epidermal nevi.

Management and Treatment

Management

Two factors influence the treatment of congenital nevomelanocytic nevi: the potential for malignant change and the cosmetic appearance.

Surgical excision with reconstruction is the mainstay of treatment. Chemical peels, dermabrasion, and laser treatments are adjunctive treatment choices. [25] All of the adjunctive treatment methods have been associated with scarring. Furthermore, adjunctive treatment measures have not been demonstrated to decrease the malignant potential. If surgical excision is not feasible, management consists of examination and high-quality photographic documentation for life.

Surgical therapy

Attempts to remove a large CNN should occur early in life, although waiting until age 6 months before operating decreases anesthetic and surgical risks. [7, 11, 20] A study by Hassanein et al indicated that serial excision is a safe and effective treatment for large CNN. The study involved 21 patients who required three or more excision procedures, for a total of 72 operations. Two procedures were followed by partial suture line dehiscence (2.8%) and one surgery was followed by seroma (1.4%). [26]

If direct closure after complete excision is not possible, reconstruction may include serial excision, excision with skin grafts, skin flaps, tissue expansion with subsequent flap rotation or full thickness skin grafting, autologous cultured human epithelium, artificial skin replacement, and free tissue transfer about tissue expansion. [7, 14, 20, 27] The goals of treatment are to remove all or as much as feasible of the CNN and reconstruct the defect, preserving function and maintaining the aesthetic appearance. Each case requires tailoring of the operation(s) to fit the anatomic defect.

A literature review by Gout et al indicated that outcomes of excision of congenital nevomelanocytic nevi vary according to the lesions’ size and location. Pooled results for CNN excision complication rates were 9.8% (major wound-related complications), 1.2% (minor wound-related complications), 1.2% (scar-related complications), and 4.3% (anatomic deformities). For large/giant nevi, wound-related complication rates were higher, as follows [28] :

-

Major wound-related complications - 23.1%

-

Minor wound-related complications - 2.9%

-

Scar-related complications - 12.9%

-

Anatomic deformities - 2.4%

The Gout study also found that for nevi with eyelid involvement, the anatomic deformity rate was 54.2%. [28]

The presence of an enlarging nodular mass indicates malignant change and requires immediate treatment. This mass may represent a rare neuroectodermal sarcoma. The incidence of malignant melanoma appears higher in the scalp, back, and buttocks and requires removal first. This increase in incidence is likely secondary to the total body surface area. Excision begins in the 6-9 month range, placing procedures 3-6 months apart.

Special attention was given to giant congenital pigmented nevi of the face by Zuker at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Complete early excision was recommended because of the cosmetic deformity and because of the life-threatening potential for malignant transformation. [29]

Cultured epidermal autografts have been used successfully to obtain surface coverage after excision of giant hairy nevi. [15] A study by Takaya et al indicated that in cultured epidermal autograft transplantation for giant congenital melanocytic nevi, removing the nevus tissue at about age 1 year, rather than at an older age, reduces the risk of hypertrophic scar formation. The investigators suggested that such scarring may also be discouraged by removing the nevus tissue via curettage, with a hydrosurgery system employed. [30]

Dermal regenerate templates (Integra) prior to skin grafting have been reported in the literature as a substitute for tissue expansion and rotation flaps. [31, 32]

Evaluation of all small and medium CNN for prophylactic excision should take place before the patient is aged 12 years. After this age, malignant potential rises sharply. [33]

Rhodes, Kaplan, and Zaal advocate prophylactic excision of all CNN, whereas Sahin believes small and medium nevi can be monitored clinically. [10, 33, 34, 35, 36]

A study by Kim et al indicated that in children undergoing excision of congenital melanocytic nevi, large nevi can be linked to more severe emergence agitation following anesthesia with sevoflurane, while younger age is a risk factor for pain and emergence agitation. Nevus location, however, was not found to be associated with pain or agitation. [37]

Adjunctive therapy

See the list below:

-

The phenol chemical peel technique has been used to treat nevi that are too large for excision or that are in locations in which excision would lead to undesirable scarring. Multiple peels were required, and the best results were in lightly pigmented, superficial lesions. Surgical excision was still deemed the primary intervention. Dermabrasion is useful as an adjunct to increase the depth of the peel and to contour surface irregularities. [38]

-

Dermabrasion independently has led to a high incidence of hypertrophic scarring (14.6%) without removal of malignancy risk. [39]

-

Multiple treatments with the normal-mode ruby laser produced immediate thermal damage to the superficial nests of nevus cells and subsequent remodeling of the superficial connective tissue. [40, 41, 42, 43]

When the thickness of the subtle microscopic scar reached 1 mm, it masked the underlying residual nevus cells and achieved a good cosmetic result.

Follow-up visits for at least 8 years after laser treatment showed no evidence of malignant change in the treated areas.

Results of ruby laser therapy have been varied and malignant risk reduction not determined.

Malignant Potential

CNN expands with growth of the child. The risk of melanoma development is proportional to the size of the congenital nevus. [10, 17, 34, 46, 47]

-

Reports of lifetime risk of developing a melanoma for patients with a large CNN range from 6.3-12.2%. Regarding giant nevi, 50% of the malignancies develop by 3 years of age, 60% by childhood, and 70% by puberty.

-

Approximately 40% of the malignant melanomas observed in children occur in large congenital nevi.

When a large congenital nevus involves the head and neck or midline over the trunk, associated meningeal melanocytosis may be observed, occasionally complicated by seizures, focal neurologic defects, obstructive hydrocephalus, or malignant changes. Radiographic imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is warranted to evaluate melanocytic depositions in the central nervous system (CNS). The baseline MRI should be obtained when the patient is aged 4-6 months. Serial MRIs are frequently required in patients with meningeal melanocytosis. [20]

Rates of malignant potential for small and medium CNN are reported between 0.8% and 4.9%. [18, 21]

-

Congenital nevomelanocytic nevus of the abdomen with a pebbled surface. Courtesy of Patricia K. Gomuwka, MD.

-

Congenital nevomelanocytic nevus of the cheek with coarse surface hairs. Courtesy of Patricia K. Gomuwka, MD.

-

Microscopic examination of specimen from the patient with an abdominal wall congenital nevomelanocytic nevus demonstrates confluence of dermal nevus cell nests and tracking along hair follicles. Courtesy of Carolyn F. Greeley, MD.