Background

Breast reconstruction after mastectomy has evolved over the last century to be an integral component in the therapy for patients with breast cancer. Breast reconstruction originally was designed to reduce postmastectomy complications and to correct chest wall deformity, but its value has been recognized to extend past this limited view of use. The goals for patients undergoing reconstruction are to correct the anatomic defect and to restore form and breast symmetry. The surgical options for breast reconstruction involve the use of endoprostheses (implants), autogenous tissue transfers, or a combination of both. [1]

Within the last few decades, the technical emphasis has focused on the use of tissue expanders with implants, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous transfer, and the transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap to achieve adequate breast restoration. [2] Although all of these methods are individually sufficient for reconstruction, surgical feasibility and patient preference dictate their use. [3]

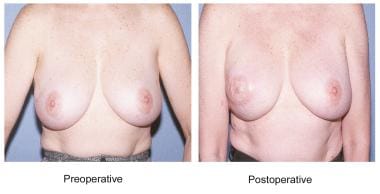

Reconstruction with the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap produces a breast with ptosis and projection while maintaining the natural consistency and feel of normal tissue. This flap provides ample bulk for reconstruction due to the large surface of the muscle. In many patients, the flap can be employed without the use of an implant, restoring volumes of up to 1.5 L in large patients or with the use of modified techniques. [4, 5] It restores the anterior chest wall with healthy tissue, particularly of benefit in patients who previously have undergone irradiation. [6] The latissimus muscle flap is a workhorse flap for salvage of failed expander-implant reconstructions. The flap also provides trophic stimulation to the surrounding tissues without increased disease morbidity or interference with mammographic evaluation. See the image below.

Using data from the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample, DeLong et al found that latissimus dorsi flaps for breast reconstruction are most often employed in delayed or salvage surgery. They also reported that treatment in younger patients tends to be more complex, with these individuals more often undergoing bilateral latissimus reconstructions, contralateral free flap reconstructions, and procedures involving implants or tissue expanders. [7]

History of the Procedure

Iginio Tansini first used the technique of transfer of the latissimus dorsi muscle on its anterior arc of rotation in 1897. [8] This Italian surgeon presented his novel concept for the coverage of chest wall defects that resulted from breast amputation as it was performed during this period. The latissimus dorsi muscle flap and overlying skin were rotated anteriorly about the axillary insertion. Later, in 1912, Stefano d'Este performed a version of this procedure described by Tansini for reconstruction of the mastectomy defect. [9]

In 1936, Hutchins went into extensive detail of his use of the latissimus dorsi for prevention of lymphedema that occurred after mastectomy. [10] He hypothesized that the ipsilateral arm and chest morbidity was due to the destruction of the axillary lymphatics and subsequent scarring that occurred after removing the pectoralis major and minor. Therefore, by re-establishing the axillary lymphatic framework imparted by these muscles with the transfer of the latissimus dorsi, he found that lymphedema could be attenuated. The latissimus dorsi was believed to be a mirror image of the pectoralis muscles, and it could serve to mimic the soft tissue defect left after removal of these structures. Hutchins described 12 successful cases in his report, in which he also noted that the latissimus dorsi transfer was useful in preventing edema while concurrently providing a healthy base for skin grafts and laying the foundation for reconstruction of the breast using transposed abdominal fat grafts.

Davis in 1949 and Darrell Campbell in 1950 made use of the flap for correction of anterior thoracic wall defects. [11, 12] Davis reconstructed a 30 x 14-cm defect created after resection of rib chondrosarcoma. [11] The lesion, which extended from the midaxillary line to the sternum and spanned the fourth to seventh ribs, was covered using a fascia lata graft and an overlying pedicle graft from the anterior portion of the latissimus muscle.

Around the same time, Campbell included the use of the latissimus dorsi anterior pedicle in a description of a procedure for repair of thoracic wall lesions that were the result of surgical extirpation of locally invasive malignancy. [12] In his procedure, he also used a fascia lata graft with latissimus dorsi, which subsequently was covered by a split-thickness skin graft. The experience of both surgeons corroborated Hutchins' findings that the latissimus dorsi anterior pedicle muscle flap was a reliable flap that provided protection and elasticity to the chest wall as well as adequate nutrition to adjacent structures.

In 1974, Brantigan published the results of 10 years of experience using the same procedure. [13] Brantigan treated 22 patients using the Hutchins modification of the radical mastectomy and reported excellent cosmetic results vis-à-vis the typical radical mastectomy. He also demonstrated the use of this flap in covering more extensive resections involving the internal mammary lymph chain, giving the surgeon the security of having mobile tissue between the pleura and skin.

The work done in the late 1970s presaged the contemporary use of the latissimus dorsi flap for breast reconstruction. With the understanding of the vascular connections to the skin provided by the underlying muscle and the idea of a myocutaneous flap proposed by McCraw in 1977, the use of the latissimus dorsi was expanded to include the overlying skin island. [14] William Schneider reported successful transfer of the muscle and skin combination. [15] He found the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap particularly useful for restoration of breast volume, replacement of the lost subclavicular contour once provided by the pectoralis major muscle, and restoration of deficient skin following mastectomy. Olivari, in 1976, [16] and Muhlbauer and Olbrisch, in 1977, [17] further exploited the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for breast reconstruction after mastectomy in patients with radiation damage to the skin and chest wall.

In 1977, Bostwick elaborated on the indication and strategy of postmastectomy breast reconstruction. [18] His experience with the latissimus dorsi flap involved 52 patients over a 2-year period and included the use of the muscle flap alone, the use of the myocutaneous island flap, and permutations of both involving silicone prostheses. His technique, with minor variation from those previously described, consistently provided adequate skin coverage and replacement of the breast mound contour, resulting in increased breast symmetry and improved cosmetic result.

Since Tansini's original idea, the latissimus dorsi flap has evolved to incorporate a wide range of applications for breast and chest wall reconstruction. The most recent advances involve subtleties in procedure and planning that have improved aesthetic and functional outcomes. Even with its loss of popularity secondary to the use of the TRAM flap in recent years, the latissimus dorsi flap remains an acceptable and reliable option for breast reconstruction in the appropriate patient population.

Indications

Patient selection

See the list below:

-

Thin habitus

-

Previous abdominal operations (including abdominoplasty)

-

Preferred dorsal donor site

-

Failed implant or TRAM reconstruction

-

Patients desiring future pregnancy

Adequate evaluation of candidates for breast reconstruction is dependent on many factors, including patient health, body habitus, contralateral breast size and shape, extent of mastectomy, site of mastectomy scar, and patient preference. Generally, healthy patients may be considered candidates for all reconstructive options, while those with significant comorbidities may be unable to tolerate complex autogenous transfers. The extent of the mastectomy defect, with consideration of the infraclavicular and axillary defects, also contributes to the reconstructive decision. Assessment of the quality of the remaining tissue and the amount of skin and soft tissue required to create acceptable symmetry ultimately impacts the decision of which procedure to perform. When an expander-implant reconstruction has failed secondary to infection or irradiated wound dehisence, the latissimus flap can be used for salvage.

Because of the increased use of the TRAM flap, the latissimus dorsi flap often is reserved for patients in whom TRAM reconstruction is contraindicated. This subset of patients includes extremely thin patients in whom the infraumbilical soft tissues are limited and patients who previously have undergone abdominoplasty or other abdominal operations or who have abdominal scars that may entail compromise of the rectus abdominis pedicle. Relative to TRAM reconstruction, the latissimus dorsi is more resistant to the effects of impaired wound healing posed by smoking and diabetes. Additionally, latissimus dorsi reconstruction does not compromise the abdominal wall, which may be of issue in patients desiring future pregnancy.

A variant of the latissimus flap is a muscle flap done through a limited axillary incision that can be used for larger lumpectomy defects. [19, 20]

See the images below.

Other post-radiation lumpectomy defects can be treated with either a standard myocutaneous flap or a perforator-based thoracodorsal flap. [21]

Relevant Anatomy

The latissimus dorsi is a flat, triangular-shaped muscle located on the posterior trunk. Its inferior origin arises from the posterior aspect of the iliac crest, lumbar fascia, supraspinal ligament, and the spines of the lower 6 thoracic vertebrate and sacral vertebrate. These muscle fibers traverse the posterior thorax cephalad and receive additional fibers of origin from the lower 4 ribs and the inferior angle of the scapula. At the level of the scapula, around the lower border of the teres major muscle, the fibers begin to merge as they form the posterior wall of the axilla. The insertion of the latissimus dorsi muscle tendon is on the crest of the lesser tubercle of the humerus anterior to the insertion of the teres major muscle.

The distribution of the muscle fibers is superficial to those of the posterior trunk (serratus anterior, serratus posterior, erector spinae) inferiorly and is deep to the trapezius at the superior medial margin. The contraction of these fibers results in the extension, adduction, and medial rotation of the humerus. When contraction is compromised, the teres major and subscapularis muscles compensate these actions.

Innervation

The innervation of the latissimus dorsi muscle is through the thoracodorsal nerve, from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. This nerve provides motor stimulus originating from the sixth through eighth cervical segments. Posterior branches of the lateral cutaneous segments of the lower intercostal nerves accomplish the sensory innervation to the skin overlying the muscle. This sensory component usually is lost due to the division of these nerves during dissection. The thoracodorsal nerve joins the thoracodorsal artery and vein 3-4 cm prior to entering the lateral edge of the muscle.

Vascular supply [22]

The blood supply to the latissimus dorsi arises from one dominant pedicle and is supported by many segmental vessels (type V pattern of circulation). The thoracodorsal artery branches from the subscapular artery just distal to the circumflex scapular artery and enters the muscle in the posterior axilla 10-11 cm inferior to the origin of its insertion. Just proximal to the entrance of the thoracodorsal artery into the muscle, it gives one or two branches to the serratus anterior. This vascular architecture allows continued perfusion if the proximal portion of the artery is damaged through collateral connections with the lateral thoracic artery. [23, 24]

The segmental arterial contribution is separated into medial and lateral rows. The medial row originates from several segmental branches of the lumbar artery and supplies the muscle origin around the lumbar spine. The posterior intercostal arteries contribute 4-6 perforators to feed the inferior lateral muscle fibers. Venous drainage is accomplished by venae comitantes of their corresponding arteries.

Coverage

The standard arc of rotation of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is based on its thoracodorsal neurovascular pedicle and humeral insertion. Posteriorly, the flap can be rotated in a cephalad orientation to cover up to the parietal skull. The anterior arc of rotation extends from the middle third of the face to the upper abdomen. Both the anterior and posterior arcs can be used to cover the anterior and posterior upper extremities, respectively, and have been used for functional muscle transfer to correct elbow flexion deformity. Additionally, the standard arc can be extended 5-10 cm in all directions with the detachment of the muscle from its humeral insertion. The standard anterior arc of rotation of the muscle flap provides transfer of the latissimus dorsi for breast reconstruction. Either an implant or expander can be used under the muscle. The advent of tabbed expanders can facilitate positional integrity of the prosthesis.

Contraindications

See the list below:

-

Posterior thoracotomy

-

Implants not desired

-

Severe cardiac disease

-

Severe pulmonary disease

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction.

-

Preoperative Lumpectomy Defect

-

Postoperative Latissimus Dorsi Reconstruction

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction; nipple reconstruction.

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction.

-

Preoperative markings.

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction; flap inset.

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction; implant placement.

-

Latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction.