Practice Essentials

Classification

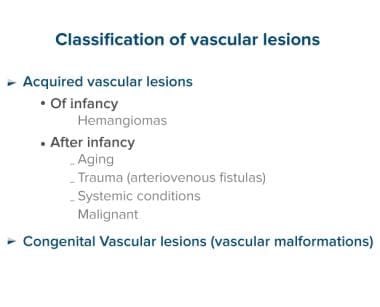

Vascular lesions of the skin can be divided into congenital and acquired lesions (see chart below).

The classification of vascular lesions is confusing, and puzzling terms such as "capillary hemangiomas" are found in some textbooks. The classification presented here is based on the type of blood vessels, type of flow, and time of presentation. [1] Exceptions exist to this division: some hemangiomas are congenital, and some vascular malformations (VMs) are not present at birth.

Congenital vascular lesions

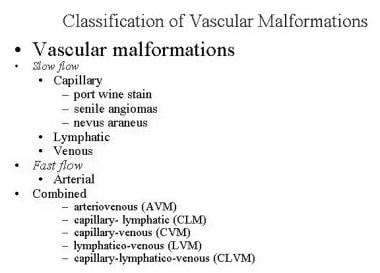

The most common congenital vascular lesions are VMs. Those lesions are the outcome of errors in vascular formation during embryonic life. VMs do not proliferate. Nevertheless, the dilated blood vessels that build up these lesions gradually enlarge. VMs can be classified based on the type of blood flow into slow-flow (capillary, venous, lymphatic) lesions, high-flow (arterial) lesions, and combined slow/fast-flow lesions (see classification below). If classified based on the size of the lymph lumens, VMs can be divided into microcystic lesions (previously termed lymphangiomas), macrocystic lesions (previously termed cystic hygromas), and a combined form.

Acquired vascular lesions

The most significant acquired vascular lesions of infancy are hemangiomas. Hemangiomas are benign but potentially destructive tumors that are composed of proliferating blood vessels. These lesions undergo proliferative and involutional stages. Pyogenic granuloma is another acquired vascular lesion that is frequently observed during childhood. [2] It is of minor aesthetic significance compared with hemangiomas. After infancy, acquired vascular lesions are associated with aging (senile angiomas), trauma (arteriovenous fistulas), systemic conditions (spider angioma), and malignancy (Kaposi sarcoma).

Workup in lymphatic vascular lesions

The most important imaging tool is contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). [3] This diagnostic test, which requires sedation or general anesthesia for children younger than 6 years, demonstrates the extent of the lesion and helps to differentiate between hemangiomas and venous, lymphatic, and arterial lesions. It also may help to differentiate between a vascular lesion and a nonvascular lesion, such as those found in neurofibromatosis.

Management of lymphatic vascular lesions

Medical therapy for lymphatic vascular lesions includes the following [4] :

-

Local pressure - Elastic support stockings may help to decrease the swelling and the functional handicap associated with lymphatic VMs of the extremities

-

Antibiotics - Viral or bacterial infection can cause acute infection of a lymphatic VM

-

Sclerotherapy - Transcutaneous injection of a sclerosant such as alcohol or sodium tetradecyl sulphate (STS) may help to decrease a lymphatic VM [5]

Surgery is the only way to "cure" a lymphatic malformation. It should be considered in the following situations [4] :

-

When intraoperative and postoperative bleeding can be controlled

-

When surgery does not put another organ at risk (eg, injury to the eye or facial nerve)

Most lesions cannot be resected completely; therefore, the extent of the resection needs to be defined before the procedure.

Epidemiology

Frequency

Lymphatic VMs are the most common bases for macrocheilia, macroglossia, macrotia, and macromelia. [6] Combined lymphaticovenous malformation (LVM) occurs particularly in the craniofacial region. [7]

A retrospective study by Wiegand et al indicated that in pediatric patients, lymphatic head and neck malformations are most commonly found in the cervical regions (47%), cheek/parotid gland (26%), tongue (17%), and orbit (8%). In study patients, malformations in the lateral neck were most often macrocystic, while those in the tongue and floor of the mouth tended to be microcystic. [8]

Etiology

The vascular system is built by 2 processes, vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. In vasculogenesis, a primitive vascular plexus is established from endothelial precursors. [9] The vascular plexus is connected to the developing heart tube, and after onset of the heartbeat, the vascular channels are perfused with blood and the primary circulation is established by the end of the third week of development. In angiogenesis, new vessels arise from these preexisting vessels by migration and proliferation of endothelial cells. [9]

In general, the endothelial cell's fate is determined by the combined effects of a large number of positive and negative signals simultaneously transduced by numerous receptors.

Many molecules have been defined that regulate vessel growth in vivo and in vitro. [9] In general, the formation and remodeling of blood vessels are controlled by paracrine signals; many are protein ligands that bind and modulate transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases. [9] Known negative regulators are angiostatin, endostatin, and thrombospondin. Positive regulators are vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibronectin, 5-integrin, vascular endothelial cadherin, and transforming growth factor-1 or TGF-1. [9]

Cha and Srinivasan suggested that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential to lymphatic vascular formation, acting as a mechanotransducer that regulates such development in association with fluid force. [10]

The lymphatic system begins to develop at the end of the fifth week. [9, 11] Lymphatic vessels develop as endothelial outgrowths from the venous system. First, 6 lymphatic sacs are formed. [9] These lymph sacs sprout from large central veins. The exact modulator that causes lymphatic VM is not known yet; however, genetic studies provide insight into the effect of positive and negative signals on the formation of those lesions. By analyzing a 2-generation family, an autosomal dominant type of congenital hereditary lymphedema has been mapped to chromosome 5. [9]

The candidate region contains a gene that encodes VEGF receptor 3 (VEGFR-3). Cervicofacial lymphatic VM further occurs in trisomy 13, 18, and 21 and in Turner syndrome. [9] Some have suggested that sporadic cases of lymphatic VM are caused by de novo dominant somatic mutations and that germline mutations are lethal. [9] Mapping of the human genome will help clarify the exact regulators that are involved in the formation of lymphatic VMs.

A study by Yan et al found a significant increase in VEGF-C and neuropilin 2 in patients with recurrent lymphatic VM microcystic lesions, compared with individuals with nonrecurrent lesions. [12]

Pathophysiology

See Etiology section above.

Presentation

The diagnosis of a vascular lesion is based on medical history, physical examination, and imaging tests. The type of lesion usually can be determined easily based on the first 2 items. Imaging studies are mostly useful for confirming the clinical diagnosis, estimating the extent of the lesion, and determining the feasibility of surgical resection.

Medical history

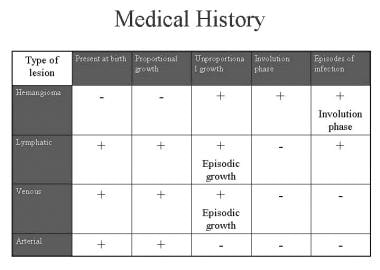

When obtaining the medical history, ask the following 4 questions:

Was the lesion present at birth?

Did proportional or disproportional growth of the lesion occur after birth?

Did an involution phase occur?

Did an episodic enlargement occur?

Clinical diagnosis of hemangiomas and venous, lymphatic, and arterial lesions can be made in a straightforward fashion based on the answers to the above questions (see chart below).

A common feature of lymphatic VM is episodic enlargement associated with systemic or localized infection. The image below shows a 5-year-old child with a right leg lymphatic VM. The right lower picture shows acute infection of the lesion with typical redness, swelling, local warmth, and high systemic fever.

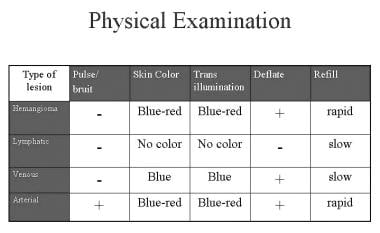

Physical examination

The physical examination of a patient with a vascular lesion includes inspection, palpation, and transillumination. The diagnosis of hemangiomas and venous, lymphatic, and arterial lesions can be made simply based on the above questions (see chart below).

Lymphatic VM can have a small and localized or an extensive presentation. Lesions that are limited to the superficial layer of the skin are called lymphangioma circumscriptum (see images below).

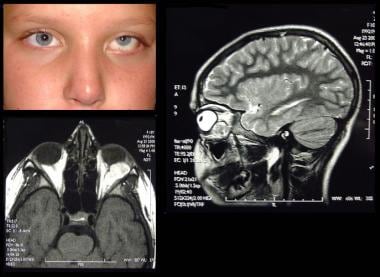

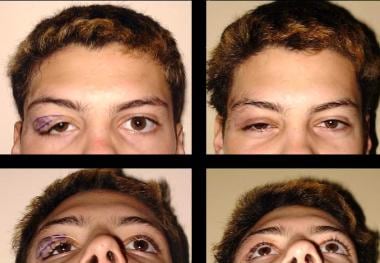

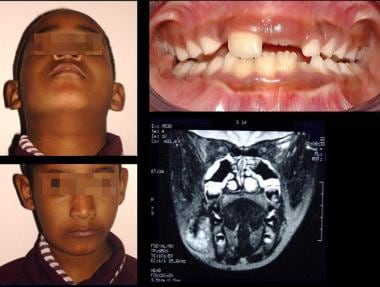

In the head and neck area, the lesions can involve the orbit and eyelids, cheek, tongue, and neck (see images below). [13]

In the extremities, lymphatic VM can present as a localized or extensive extremity lesion associated with lymphedema and dysfunction (see images below).

Skeletal distortion and hypertrophy are also common features of limb and facial lymphatic malformations. The image below shows the effect of a cheek lymphatic malformation on the mandible.

Assessment of asymmetry and deformity of the facial and limb skeleton should be part of the physical examination of patients with lymphatic VMs.

Differential diagnosis

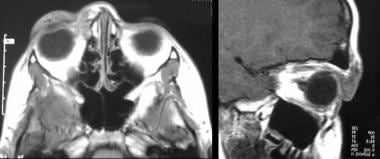

Lymphatic VMs may be confused with deep hemangiomas or venous VMs. The presence of the lesion at birth supports the diagnosis of a VM, although congenital hemangiomas can be observed at birth. MRI can help to distinguish between a VM and a hemangioma. The differential diagnosis also includes gliomas, benign tumors, and malignant tumors. The image below shows the differential diagnosis of orbital lymphatic VMs.

Indications

Lymphatic VMs never involute. They expand or contract depending on the ebb and flow of lymphatic fluid and the occurrence of inflammation and intralesional bleeding. [6] Several indications for treatment exist. The size and location of the lesion, recurrent infection, and pain are the most frequent indications for treatment. [5]

In the aforementioned report by Wiegand and colleagues on pediatric patients with lymphatic malformations, use of the de Serres classification system indicated that the site of the lesion significantly impacts symptoms and functional deficits. In study patients, the Cologne Disease Score, which takes into account disfigurement, dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea, was considerably more severe for de Serres stage IV (bilateral suprahyoidal) and V (bilateral suprahyoidal and infrahyoidal) malformations than for those in other locations. [8]

Vision

An intraorbital lesion usually presents as proptosis. It may expand rapidly and cause optic nerve compression, disk swelling, and decreased vision. Cysts filled with blood ("chocolate" cysts) or lymph fluid may be aspirated under ultrasonographic guidance. Currently, no well-tested pharmacologic treatments for lymphatic VMs are available. Preliminary studies demonstrate that OK-432 may be useful for intralesional injection. [14] Surgery may be indicated for superficial eyelid lesions and in selected patients with intraorbital lesions. Sufficient surgical excision of orbital tumors without injury to intervening structures is difficult.

The first image below shows a 14-year-old boy with a right upper eyelid lymphatic lesion that had caused ptosis of the right upper eyelid (images on left). The second image shows an MRI of the lesion. Improvement in his visual field was achieved after excision of the lesion.

Breathing

Sublaryngeal lesions may compress the soft tracheal rings of infants. Intralesional injection with alcohol may be successful in macrocystic lesions but also may be followed by acute swelling and airway obstruction. [15] Tracheostomy may be required in selected patients.

A nationwide Japanese survey by Ueno et al of children with head and neck lymphatic malformation (in whom the mediastinum was not involved), found that in over 70% of patients who underwent tracheostomy, the associated lesion was in contact with the airway. However, such contact occurred in only 12% of children who were not treated with tracheostomy. [16]

Limb function

Localized limb lesions (see images below) are mostly of aesthetic concern.

Large lesions (see images below) may be associated with functional handicap. Treatment may be indicated in such individuals.

Recurrent infections

Infections as part of a systemic disease or as a localized problem are frequently observed in patients with lymphatic VMs. The image below (lower right) shows acute infection of a lower limb lesion. Long-term antibiotic treatment and compression stockings may decrease the incidence of infections.

Hygiene

Lymphatic lesions with a superficial component are associated with chronic shedding of small cysts, lymph leak, staining, and an unpleasant odor. The image below shows a 12-year-old boy with a lymphatic lesion involving the entire right leg. Good hygiene was very difficult to maintain at the toe area.

Aesthetic concerns

Lesions that involve the head and neck area may be associated with significant aesthetic deformity. The images below show some common head and neck lesions with aesthetic deformities. Parental concerns and the psychosocial effect of the deformity on the growing child should be taken into consideration and may be indications for early treatment. [15]

Relevant Anatomy

Normal lymphatic capillaries consist of single-layer endothelial cells without surrounding pericytes and without valves. These lymphatic capillaries merge into collecting lymphatic vessels, [9] which consist of a thin endothelial lining, surrounded by an incomplete layer of smooth muscle cells, with valves. Finally, either the thoracic or the right lymphatic duct delivers lymph to the venous system. Their walls contain a tunica intima, media, and adventitia, with the media containing bundles of smooth muscle cells. [9]

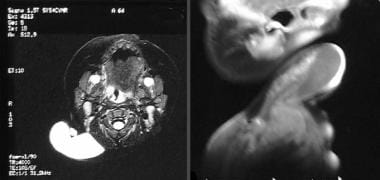

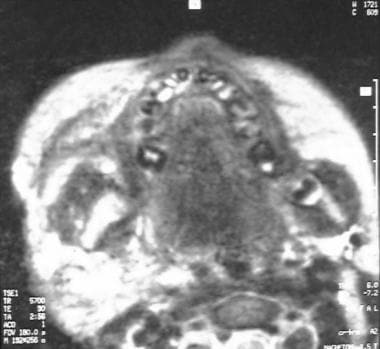

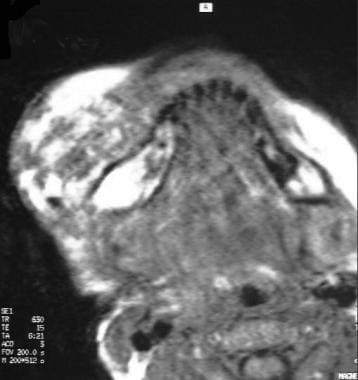

Lymphatic VMs are composed of dilated lymphatic channels. [9] They are filled with a proteinaceous fluid and do not have connections to the normal lymphatic system. Lesions can be primarily macrocystic or microcystic. Thoracic lesions are usually macrocystic and cervicofacial lesions are usually microcystic. [9] Lesions are located at the skin and subcutaneous tissue but may invade the floor of the mouth, cheek muscles, and other anatomic structures. The images below show an MRI of a 9-year-old child with a right facial lesion that extended into the floor of the mouth and cheek.

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted spin-echo image showing rim enhancement, which is typical of lymphatic vascular malformations.

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted spin-echo image showing rim enhancement, which is typical of lymphatic vascular malformations.

Contraindications

Sclerotherapy may be contraindicated in the following situations:

-

Patient is allergic to the sclerosant or contrast media.

-

Patient has a cardiac condition.

-

Bleeding cannot be controlled.

-

Systemic leak of the sclerosant cannot be avoided.

-

Significant skin or mucosal injury is expected.

-

Postinjection swelling puts another organ at risk (eg, injury to the optic nerve).

-

Postinjection airway swelling cannot be managed by a tracheal tube or tracheostomy.

Surgery may be contraindicated in the following situations:

-

Intraoperative and postoperative bleeding cannot be controlled.

-

Surgery puts another organ at risk (eg, injury to the eye or facial nerve).

-

Classification of vascular lesions.

-

Classification of vascular malformations.

-

Diagnosis - Medical history.

-

Lower limb lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Diagnosis - Physical examination.

-

Lymphangioma circumscriptum.

-

Thigh lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Orbital lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Eyelid lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

MRI of eyelid lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Right facial lymphatic vascular malformation with right open bite.

-

Gradual enlargement of a facial vascular malformation.

-

Tongue lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Cystic hygroma.

-

MRI of cystic hygroma.

-

Neck lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Axillary lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted spin-echo image of a venous-lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Large axillary venous-lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Huge upper limb lymphatic malformation.

-

Lower limb lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Panorex showing mandibular hypertrophy due to a lymphatic vascular malformation.

-

Venous or lymphatic lesion on T2-weighted spin-echo image.

-

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted spin-echo image showing rim enhancement, which is typical of lymphatic vascular malformations.

-

Contrast-enhanced (gadolinium) T1-weighted spin-echo image showing areas with rim enhancement, which are typical of lymphatic vascular malformations.

-

MRI - MRI T1, T2.

-

Diagnosis – MRI.

-

Orbital hemangioma - Differential diagnosis.

-

Complications of alcohol injection.