Overview

The history of nasal reconstruction mirrors the history of plastic surgery, beginning with what commonly is believed to be the earliest plastic surgery procedure recorded—nasal reconstruction by Sushruta in India during 600-700 BC, as reported by Rogers. [1] Reconstruction of the nose again emerged in 1597 when Tagliacozzi published a technique of a staged transfer of skin from the arm to rebuild the nose. [2] The emergence of these techniques in history undoubtedly is related to the savagery of hand-to-hand combat and the practice of cutting off the nose as a punishment for crimes.

Since the 19th century, a variety of nasal reconstruction procedures that use local tissue from the nose, cheek, and forehead have been described. Reconstruction of the nasal skeleton using grafts from the nasal septum, ear, rib, hip, and calvaria also was introduced. Skin grafts were introduced in the 19th century as an option for defects with adequate soft tissue covering. The more recent development of the techniques of microsurgery, tissue expansion, and prefabricated flaps has added to the armamentarium of the plastic surgeon confronted with a complex nasal defect.

The contemporary plastic surgeon now has an almost bewildering number of reconstructive options from which to select. However, the rich history of nasal reconstruction is perhaps most impressive because the first procedure described, the midline forehead flap, remains a commonly used flap for nasal reconstruction. [3]

Surgical anatomy

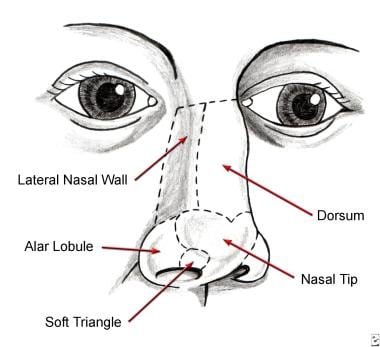

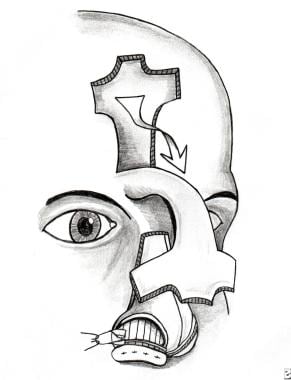

The nose is a composite tissue structure composed of the nasal skeleton, an internal lining of mucosa, and an external layer of skin. The topography of the external nose is a graceful blend of convexities, curves, and depressions that reflect the underlying shape of the nasal skeleton. These characteristics allow division of the nose into aesthetic subunits, described by Millard and modified by Burget: the tip and dorsum in the midline and the surrounding soft triangles, alar lobules, and lateral walls (see image below). [4, 5, 6]

Consider the aesthetic subunits of the nose whenever planning a reconstruction. The borders of the subunits are an ideal location for the placement of scars, and an aesthetic subunit reconstructed with a uniform color and texture generally yields a superior result.

Noel et al indicated that the hemitip should be included among the aesthetic subunits, stating that their retrospective study found that in most cases, when there is a defect on just one side of the tip, hemitip aesthetic subunit reconstruction is beneficial. The investigators also stated that a midline scar between the two hemitips is not easily seen. [7]

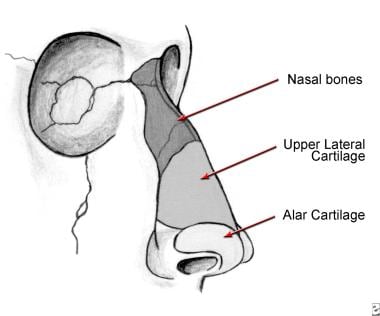

The nasal skeleton (see image below) is the supporting structure of the nose, and its integrity either must be maintained or restored for a successful reconstruction. It consists of the nasal bones and ascending processes of the maxilla in the upper one third, the paired upper lateral cartilages in the middle third, and the lower lateral, or alar, cartilages in the lower one third.

The upper lateral cartilages are attached tightly to the caudal edge of the nasal bones and the nasal septum, which allows them to remain suspended above the nasal cavity. The paired alar cartilages support the lower one third of the nose by uniting to form a tripod configuration.

The paired medial crura form the central leg of the tripod and are attached to the anterior nasal spine and septum in the midline. The lateral crura comprise the two lateral legs of the tripod, and they are attached firmly to the pyriform aperture. The dome defines the apex of the alar cartilage. It supports the nasal tip and is responsible for the light reflex of the tip.

The nasal lining consists of a thin layer of vascular mucosa. It tightly adheres to the deep surface of the nasal bones and cartilages. This dense adherence limits the mobility of the mucosa, and consequently only the smallest mucosal defects (< 5 mm) can be closed primarily.

The skin is the third and final layer of the nose. Proceeding inferiorly from the glabella, the skin thickness decreases and becomes progressively less distensible. The skin of the middle third of the nose over the cartilaginous dorsum and upper lateral cartilages is somewhat mobile, but at the distal third of the nose the skin tightly adheres to the alar cartilages, limiting its mobility.

The skin and underlying soft tissues of the alar lobule form a semirigid unit that maintains the graceful curve of the alar rim and the patency of the anterior nares. To preserve this shape and patency, replacement of the alar lobule must include a cartilage graft for support, even though it does not contain cartilage in its native state.

The skin of the nose has a smooth and oily texture as a result of the high density of sebaceous glands. Compared to other areas of the face, the nose is forgiving with respect to scar formation, and it is perhaps second only to eyelid skin in its tendency to form fine, inconspicuous scars. The combination of favorable scar formation and the strategic placement of scars offers the plastic surgeon the opportunity for excellent results in nasal reconstruction.

Basic principles

Burget elegantly described the basic principles of nasal reconstruction in 1985. [5] They are extensions of the essential principles that define plastic surgery, and their observation provides the clearest path to outstanding results.

-

Restoration of "normal"

The surgeon's ultimate goal should be to recreate the shadows, contours, color, and texture that define the normal nose at conversational distance (approximately 3 ft). However, this approach often leads to the selection of more complex procedures; this must be tempered by the needs and requests of the patient.

Consider medical risk factors, especially when longer or multiple-stage procedures are contemplated. Also consider the patient's priorities. Ask each patient if he or she prefers a procedure that the surgeon believes produces the best aesthetic result, even if it is the most complex and riskiest, or if he or she prefers a simpler, low-risk procedure that may produce a lesser result. The answer to this question is quite revealing and helps to guide the surgeon and patient in the selection process.

-

Replacement

Replace missing parts with tissue that is like in quality and quantity. Replace nasal lining with lining, cartilage with cartilage, bone with bone, and skin with skin that is the closest match in color and texture. The author generally prefers skin flaps to skin grafts because they generally provide a superior match in color and texture, are resistant to contracture, and are able to provide vascular covering to the nasal skeleton.

The best source of nasal skin is nasal skin, when sufficient quantity exists. The use of nasal skin flaps should be a prime consideration, because the perfect color and texture match outweighs the disadvantage of additional scarring in most situations.

-

Template

The template for replacing missing parts is the 3-dimensional configuration of the "normal nose." Create this using a firm but malleable material; the foil of an empty suture packet is an ideal source.

With a partial defect, such as the alar lobule, the contralateral side becomes the model, and the foil is molded directly over the normal anatomy. For total nasal reconstruction, use a mental image obtained from continuous scrutiny of the "normal nose" in daily life to create a lifelike template.

-

Skin

At the skin level, replace entire aesthetic subunits whenever practical, even if it means enlarging the size of the defect. This principle allows the placement of scars that are less conspicuous, because they lie in the transition zone between adjacent aesthetic subunits. It also avoids the placement of two types of skin in the same subunit, which may be quite noticeable even when flaps are used.

However, exercise this principle judiciously, weighing the advantages of scar placement and skin match against the additional flap or graft requirements and potential complications of a larger defect.

-

Scar placement

Place scars in the least conspicuous location possible.

This principle applies both to the borders of skin grafts and flaps and to donor site scars.

-

Final stage

Anticipate a final stage in which the subcutaneous tissue is sculpted to replicate the delicate configuration of the "normal nose."

Minor scar revisions also can be performed at this time when necessary.

Indications

See the list below:

-

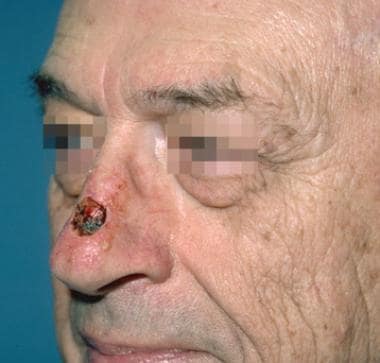

The most common etiology of nasal defects that require reconstruction is skin cancer, particularly basal cell carcinoma, the most common nasal skin cancer, as well as squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. The epidemiology favors those in geographic areas of high sun exposure and elderly persons, especially those of fair-skinned, Celtic origin.

-

Traumatic nasal defects are much less common, but the principles of restoration are the same as for oncologic defects, except that the patient population is younger and donor site scars are more noticeable. Therefore, strategic placement of scars is even more critical.

-

A third category of nasal deformities is congenital. However, congenital deformities have unique properties and associated anomalies that merit a separate discussion, thus they are not considered in this article. For more information, see eMedicine Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic Surgery article Congenital Malformations, Nose.

Technique

The success of every operation lies in the details. To master nasal reconstruction, one must master the details of a set of flaps that, taken together, constitute an armamentarium in restoration of the nasal envelope—the "workhorse" flaps. This section is devoted to a precise description of flaps of choice used by the author to reconstruct defects of the nasal skin and lining.

Bilobed flap

The classic design of the bilobed flap was based on the creation of two adjacent random transposition flaps. According to the original design, the leading flap is used to cover the defect, and the second flap, placed at an area of greater skin mobility, fills the donor site wound from the first flap; its donor site then is closed primarily. Geometrically, the first flap is oriented 90° from the axis of the defect, and the second flap is oriented 180° from the axis of the defect. This technique was effective, but it created troublesome "dog ears" and a broad area of donor skin that was difficult to confine to the nose.

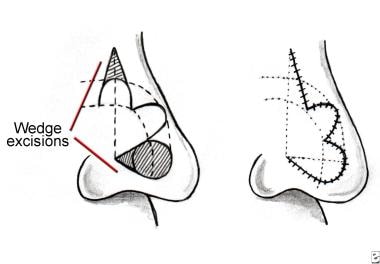

In 1989, Zitelli described a modification of the bilobed flap, which is the basis of the technique described here. [8] In Zitelli's modification (see image below), the leading flap (a) is oriented 45° from the axis of the defect, and the second flap (b) is oriented 90° from the axis of the defect. These changes eliminate "dog ears," require a smaller surface area of donor skin, and result in broader based flaps that are less prone to the "trap door" or "pin cushion" deformities that can be observed with transposition flaps.

Technique for bilobed flap (see image below)

Bilobed flap. The flap is designed with the long axis of the defect, and each lobe of the flap is separated by 45° angles. The two lobes of the flap rotate along a perfect arc with all points on the arc equidistant from the apex of the defect.

Bilobed flap. The flap is designed with the long axis of the defect, and each lobe of the flap is separated by 45° angles. The two lobes of the flap rotate along a perfect arc with all points on the arc equidistant from the apex of the defect.

The following steps are employed in the bilobed flap technique:

-

Select the location of the bilobed flap and the orientation of the pedicle based on the amount of available nasal skin. If the defect is on the lateral aspect of the nose, base the pedicle medially; if the defect lies on the nasal tip or dorsum, base the flap laterally. An ideal location for the second flap is along the junction of the nasal dorsum and lateral nasal wall.

-

Convert the defect to a "tear drop" shape by the excision of a Burrow triangle on the side of pedicle base.

-

Use a 20-mm caliper as a protractor, with one tip placed at the apex of the wound, to mark out two semicircles. The outer semicircle defines the necessary length of the two lobes, and the inner semicircle bisects the center of the original wound and continues across the donor skin. The inner semicircle defines the limit of the common pedicle of the two lobes.

-

Then draw two lines from the apex of the wound: the first line is placed 45° from the axis of the wound, and the second line is placed 90° from the axis of the wound. These two lines mark the central axes of the two lobes of the flap.

-

Draw the flap with each lobe beginning and ending at the inner semicircle and extending to the outer semicircle at the point where it crosses its central axis. The width of the first lobe is approximately 2 mm less than the width of the defect, and the width of the second lobe is approximately 2 mm less than the width of the first.

-

Incise the bilobed flap and elevate it in a plane between the subcutaneous fat and nasalis muscle. Deepening the recipient wound down to the nasal skeleton, which almost always accommodates the thickness of this flap, is safer than thinning the flap.

-

Undermine the donor site of the second lobe as needed to allow primary closure. Excise any "dog ears" at the donor site. If the donor site cannot be closed or the skin blanches upon closure because of tension, decreasing the size of the wound with deep sutures and allowing it to heal by secondary intention is preferable.

A retrospective, single-surgeon study by Okland et al found the bilobed flap to be effective in small nasal tip defect repair. According to the investigators, thinning the transposition flap through removal of excess subcutaneous tissue aids aesthetic outcomes and minimizes the incidence of pincushioning and the need for revision surgery. Of 125 patients, 20 (16%) reportedly experienced complications, including scars, pincushioning, and nasal obstruction. Revision surgery, including scar revision, was performed in five patients (4%). [9]

Although typically, bilobed and trilobed transposition flaps are not employed for nasal defects that are 15 mm or larger, a study by Stiff et al indicated that these flaps can successfully be used to repair such wounds in the intermediate (15 mm or greater) or large (20 mm or greater) size range. The mean defect size in the report’s 34 patients was 18 mm, with, at minimum 5-week follow-up, the mean provider validated scar scale (SCAR) score being 3.06 (best to worse: 0-13) and the mean score for the patient component of the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) being 10.93 (best to worst: 6-60). Nine patients (26.5%) required scar revision. No major postoperative events occurred. [10]

Nasolabial flap

Dieffenbach, with contributions from other plastic surgeons, popularized the nasolabial flap for nasal reconstruction in the 19th century. [11] It remains one of the most useful flaps in nasal reconstruction.

The nasolabial flap can be superiorly or inferiorly based, but the author has found the superiorly based flap more useful because it has a more versatile arc of rotation and the donor site scar is less noticeable. The base of the pedicle either can be incorporated into the reconstruction or divided at a second stage, depending on the configuration of the defect. It is supplied by transverse branches from the contralateral angular artery and by a confluence of vessels from the angular and supraorbital arteries located inside the medial canthus. Therefore, never continue flap incisions superiorly beyond the medial canthal tendon.

The nasolabial flap is a random flap, because the proximal portion lies on the lateral wall of the nose; only the distal portion of the flap on the cheek contains the main angular artery, and it is perfused by retrograde arterial flow.

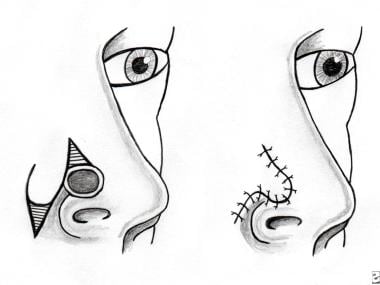

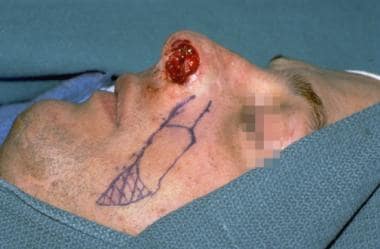

Technique for nasolabial flap (see image below)

Nasolabial flap. The base of the pedicle of this flap lies on the lateral nasal wall and is transposed a maximum of 60° to avoid a "bridge" effect of the flap crossing the nasofacial angle.

Nasolabial flap. The base of the pedicle of this flap lies on the lateral nasal wall and is transposed a maximum of 60° to avoid a "bridge" effect of the flap crossing the nasofacial angle.

See the list below:

-

Design the flap with the central axis 45° from the axis of the nasal dorsum. Base the shape of the flap on a template taken from the defect.

-

Incise the flap without the injection of epinephrine and elevate it between the subcutaneous fat and muscle fascia in an inferior-to-superior direction.

-

Continue dissection until the flap can be transposed freely over the nasal defect. A triangular segment of skin must be excised between the medial border of the flap and the nasal dorsum, and this can be accomplished either before or after elevation of the flap.

-

The flap then is reflected and can be thinned out under loupe magnification but remember that it does not tolerate debulking as well as an axial flap.

-

Inset the flap and begin donor site closure. The donor site can be closed primarily for defects of the lateral nose that are less than 15 mm in width. For larger defects, especially those including the alar lobule and lateral wall, primary closure places unwanted tension on the flap. Instead, advance the cheek skin to the nasofacial junction and suture it to the deep tissues. A narrow wound, almost always 1 cm or less, is left to heal by secondary intention.

Forehead flap

The forehead flap is the premier flap in nasal reconstruction. It can be used to replace any or all of the aesthetic subunits, and it provides an excellent color and thickness match. The forehead flap is an axial flap based on the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels; thus, it can be thinned down to the subdermal plexus, enhancing the final result.

A disadvantage of the forehead flap is that it requires a 2-stage procedure, which may be a factor in patients with significant medical risk factors, although the second stage can be performed under local anesthesia. A second disadvantage is that although the donor site scar heals favorably, it is difficult to conceal, especially in men.

One limitation of the forehead flap is that its length may be restricted by a low frontal hairline. In such patients, a small amount of scalp skin can be included in the flap but it has a different texture and continues to grow hair. An alternative is to curve the flap transversely along the hairline but this portion of the flap is random and has a higher risk for necrosis.

Technique for forehead flap (see image below)

Paramedian forehead flap. This flap is designed using a foil template of the defect. Its pedicle is centered on the Doppler signal of the supraorbital artery, and the distal one half of the flap is thinned down to the subdermal plexus.

Paramedian forehead flap. This flap is designed using a foil template of the defect. Its pedicle is centered on the Doppler signal of the supraorbital artery, and the distal one half of the flap is thinned down to the subdermal plexus.

See the list below:

-

Make an exact foil template of the nasal defect as described in Basic Principles.

-

Identify the axial pedicle, composed of the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels, with a Doppler ultrasonic scanner at the base of the flap adjacent to the medial brow. This point almost always lies between the midline and the supraorbital notch.

-

Trace the pulse out as far distally as possible and then continue it as a vertical line to the hairline. This line is the central axis of the flap.

-

Determine the length of the flap by placing an opened 4 X 4 gauze from the pedicle base to the most distal point of the defect in a tension-free manner. Transfer this length to the central axis.

-

Turn the template 180°, place it over the distal portion of the axis of the flap, and then outline it with a surgical marker. Continue these markings proximally parallel to the central axis, maintaining a 2-cm width for the proximal flap.

-

Incise the flap without the injection of epinephrine and elevate the distal one half between the frontalis muscle and subcutaneous fat.

-

At approximately the mid portion of the forehead, deepen the plane of dissection to the submuscular plane. Continue dissection toward the brow and glabella until sufficient mobility is obtained to allow a tension-free transposition.

-

Defat the distal portion of the flap under loupe magnification down to the subdermal plexus. This step should be conservative if the patient has factors that negatively affect blood flow, such as diabetes or smoking.

-

Allow the flap to perfuse while the donor site is closed by wide undermining deep to the frontalis muscle. At this time, some dilute epinephrine may be injected into the forehead skin but not near the pedicle. If the distal wound is wider than 25 mm, it usually does not close primarily and should be left to heal by secondary intention.

-

Attach the flap using subcutaneous and skin sutures. If a suture is placed and it appears to compromise the color of the flap, it can be loosened with a skin hook and observed for 10 or 15 minutes. However, if the color does not improve, this suture needs to be removed.

-

Complete flap attachment and dress the wounds with antibiotic ointment only.

Septal mucosal flap

The septal mucosal flap is used for almost all large defects of the nasal lining. This technique was described by Millard in 1967 [12] and modified by Burget and Menick. [13] It is an anteriorly based flap supplied by the septal branch of the superior labial artery. It is used for defects of the distal one half of the nose, and the entire septal mucoperichondrium can be harvested. Burget has described a modification of the septal mucosal flap described by Millard; this is the basis for the description of this technique.

Technique for septal mucosal flap (see image below)

Septal mucosal flap. This anteriorly based flap is cut as wide as possible and released with a low posterior back cut only as needed to turn the flap into the defect.

Septal mucosal flap. This anteriorly based flap is cut as wide as possible and released with a low posterior back cut only as needed to turn the flap into the defect.

See the list below:

-

Measure the dimensions of the defect and mark them out on the septum, incorporating an extra 3-5 mm, if possible.

-

Make 2 parallel incisions along the floor and roof of the nasal septum, converging anteriorly towards the anterior nasal spine. The base of the pedicle should be at least 1.5 cm wide.

-

Dissect the flap with an elevator in a submucoperichondrial plane. Then cut the distal edge of the flap with a right-angle Beaver blade and transpose the flap into the defect. The exposed cartilage will re-epithelialize as long as the contralateral septal mucosa is left undisturbed.

-

A variation of this technique, which can be used to reconstruct one side of the upper half of the nasal lining, is the superiorly based septal mucosal "trap door" flap. This is a random, rectangular flap with its pedicle based at the junction of the septum and lateral nasal skeleton in the contralateral nasal cavity. Elevate this flap to the roof of the septum and pass it into the contralateral nasal cavity through a slit created by removing a small portion of the dorsal roof of the septum. Then stretch it across the lining defect of the lateral nose.

Other flaps

In a study of patients who underwent alar or nasal tip reconstruction, primarily after tumor ablation, Kim et al reported that both S-shaped rotation flaps and croissant-shaped, modified V-Y flaps are cosmetically and therapeutically effective for cutaneous defects of approximately 4.0 cm2 or less. The investigators stated that these local flaps require less dissection than do bilobed and other local flaps. [14]

Management of Specific Nasal Defects

Textbook references for nasal reconstruction understandably strive to be comprehensive in their treatment of this topic and consequently include most, if not all, of the techniques that have been described. However, these references often fail to answer the core question: "What should I do and when should I do it?"

The purpose of this section is to convey the primary techniques that have been successful for the author and answer this core question. It is not meant to discredit other approaches but to allow the reader to become intimately acquainted and proficient with a manageable list of procedures that satisfy all types of defects. [15, 16]

Partial-thickness defects

For the purpose of this discussion, partial-thickness defects are defined as wounds in which adequate soft tissue covers the underlying nasal skeleton. If the wound is too large to be closed primarily, which varies by location, the next options to consider are healing by secondary intention and full-thickness skin grafts. [17]

Healing by secondary intention can yield surprisingly good results for defects up to 10 mm in diameter. This approach avoids the patchlike appearance of a skin graft, and if the scar is unsatisfactory, it can be revised easily at a later time.

Larger defects eventually heal by this approach as well but they often produce a wide, atrophic patch of scar that is inferior to that produced with other techniques. However, the skin of the medial canthus is an exception. This is discussed in detail under full-thickness defects.

A second drawback to healing by secondary intention is that wound contracture may distort the normal anatomy, which can lead to a pronounced deformity in the area around the alar rim. For this reason, healing by secondary intention generally is not recommended for defects of the distal one third of the nose, with the exception of small wounds directly over the nasal tip.

Full-thickness skin grafts continue to be an effective technique for the management of defects with a well-vascularized soft tissue bed covering the nasal skeleton. Preauricular skin and postauricular skin are the preferred donor sites, and a small amount of adipose tissue may be left on the graft for soft tissue filler. Avoid neck skin because of the low density of pilosebaceous units, which is in sharp contrast to the characteristics of nasal skin.

The advantages of skin grafts are that they are fast, simple, and have low donor site morbidity. The best results appear to be for shallow wounds with enough soft tissue support to prevent a conspicuous depression. One disadvantage is a color and texture mismatch, which may result in a patchlike appearance, although this effect often is not very noticeable in fair-skinned individuals. A second disadvantage is the natural tendency for grafts to contract, which may distort the shape of the nose.

Full-thickness defects

This section considers full-thickness defects of 3 types: wounds of the skin and soft tissue with exposure of bone and/or cartilage, wounds extending through the nasal skeleton, and wounds traversing all 3 layers of the nose.

In the management of full-thickness defects, factors considered in the selection of the reconstructive technique are the size and location of the defect and the number of missing tissue layers. For the purpose of discussion, each of the aesthetic subunits is considered separately and in combination.

Medial canthus

The nasal skin between the dorsum and the medial canthal tendon is uniquely suited to healing by secondary intention, and results often are superior to those achieved with either skin grafts or flaps. The medial canthal tendon is fixed securely in bone, thus resistant to the forces of wound contracture. The animation of the medial brow also lends resistance to these forces. In addition, this region is hidden by the shadows of the nasal dorsum and supraorbital rim, obscuring any differences in quality of the replacement epithelium.

Healing by secondary intention occurs even when the defect extends down to the bone. Defects measuring up to 10 mm typically heal in approximately 4 weeks although the rate of healing depends on the overall wound healing capacity of the individual patient. One potential complication of this approach is the formation of a medial canthal web, but this is an uncommon occurrence and can be corrected using the technique of double opposing Z-plasties.

Nasal dorsum and lateral nasal wall

The technique chosen for skin replacement in these two aesthetic subunits is dictated by the size of the defect. Defects measuring less than 10 mm in greatest diameter can be managed either by primary closure or by secondary intention.

For defects from 10-15 mm, the modified bilobed flap is a versatile, single-stage technique that can yield outstanding results. Its greatest advantage is that it provides the best color and texture match. Although not all of the scars can be hidden at the margins of aesthetic subunits, the superior scar formation on the nose minimizes this disadvantage, and this is the author's flap of choice for defects in this size range.

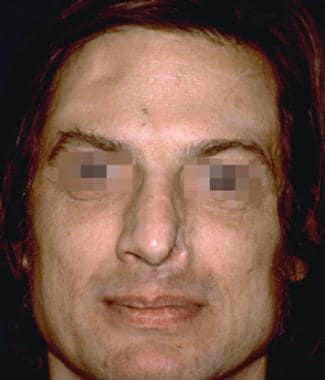

Case 1 (see images below):

Case 1. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12-mm full-thickness skin defect of the nasal dorsum.

Case 1. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12-mm full-thickness skin defect of the nasal dorsum.

This patient presented after Mohs excision of a basal cell carcinoma with an 11-mm full-thickness skin defect down to bone and cartilage. His nose was reconstructed with a laterally based bilobed flap. The axis of the second lobe was placed at the junction of the nasal dorsum and lateral wall of the nose to hide the scar. The result is shown 4 months after surgery.

For defects greater than 15 mm, the flap of choice is the paramedian forehead flap. It can be used to reconstruct either the entire nasal dorsum or lateral wall of the nose. When managing defects of this size, it is preferable to enlarge the defect when necessary to comprise the entire aesthetic subunit. If the wound involves both the dorsum and lateral wall of the nose, use a cheek advancement flap to replace the lateral nasal skin up to its junction with the dorsum. Then use the forehead flap to resurface the nasal dorsum.

An alternative to both the bilobed flap and the forehead flap for variously sized defects of the lateral wall of the nose is the superiorly based nasolabial flap. It is particularly well suited for distal defects that lie between the convexities of the nasal tip and alar lobule. This flap can be used for defects involving the distal two thirds of the nose as long as sufficient skin is present superiorly to construct the base of the pedicle. For defects greater than 15 mm in width, the donor site cannot be closed primarily.

The main disadvantage of this flap is that it tends to be bulkier, except in elderly patients with atrophic cheek skin. However, it is an effective technique for patients who are not candidates for a 2-stage forehead flap.

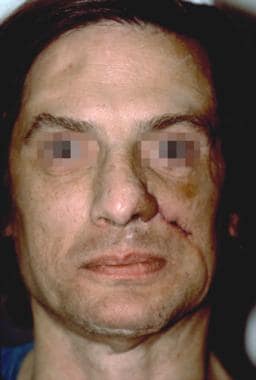

Case 2 (see images below):

Case 2. Intraoperative design of a superiorly based nasolabial flap for a full-thickness skin defect involving portions of the tip, ala, and lateral wall of the nose.

Case 2. Intraoperative design of a superiorly based nasolabial flap for a full-thickness skin defect involving portions of the tip, ala, and lateral wall of the nose.

This patient presented after excision of a basal cell carcinoma of the distal lateral wall of the nose. He had a defect of the lateral wall that also involved part of the nasal tip and alar lobule. His nose was reconstructed with a single stage, superiorly based nasolabial flap. He is shown 6 months after surgery. This case demonstrates how the atrophic cheek skin of elderly patients provides an excellent match in skin thickness.

Defects involving the bone or cartilage of the lateral nose are managed effectively with flat pieces of septal bone and cartilage as free grafts. Small defects of the nasal dorsum also can be covered with cartilage grafts from either the septum or concha of the ear. Larger dorsal defects require the stable support of a bone graft, and the best results have been obtained when rigid fixation is used either with a lag screw or a low profile plate. The author prefers rib because it can be harvested with an extension of cartilage that can be sculpted to blend with the nasal tip. Other potential donor sites are the outer table of the skull, the iliac crest, or the inner table of the ilium.

If the nasal lining of the upper two thirds of the nose is deficient, the reconstructive technique depends on the size of the defect. Lining defects less than 5 mm in diameter can be closed primarily. Wounds from 5-15 mm can be closed using random transposition flaps from an area that remains protected by the nasal bones or upper lateral cartilages. The donor site can be left to heal by secondary intention. For defects greater than 15 mm, a superiorly based "trap door" septal mucosal flap based at the roof of the septum (see Septal Mucosal Flap) can be used.

Nasal tip

The average width of the nasal tip, measured between the two alar lobules, is approximately 25 mm, with a range of 20-30 mm. If the greatest diameter of the skin defect is less than 15 mm, it can be managed effectively with a bilobed flap. The wound should not be enlarged in this situation to fill the entire subunit, but the wound margins should be reshaped to match the natural curve at the border of the nasal tip. If the wound is eccentric, position the flap with a lateral base on the side that occupies the largest portion of the defect. [18]

If the defect is greater than 15 mm in diameter, enlarge it to include the complete aesthetic subunit and reconstruct it with a forehead flap. If the defect also involves the nasal dorsum, the entire tip and dorsum can be replaced with a forehead flap.

If part or all of the alar cartilages are missing, they must be replaced with cartilage grafts. Defects of the alar domes in which adequate support of the tripod configuration remains can be treated with an onlay graft from either the septum or conchal cartilage. Carve the graft in the shape of a shield, with the widest margins at the normal location of the domes. Typically, stacking the graft in two layers is necessary to transmit the desired light reflex seen on the nasal tip.

Defects confined to the lateral crura can be replaced with a flat strut of cartilage, but if the support of the medial crura is absent, a columella strut must be inserted and attached at the level of the anterior nasal spine. Septal cartilage can be used, but if it appears to be too weak, rib cartilage is an excellent donor site. Onlay grafts then can be placed over the strut.

In the unusual situation of complete loss of the alar cartilages, they can be replaced using all of the conchal cartilage from both ears. Take two strips, each 10 mm wide, directly inside the antihelical fold and use them to replace the alar wings. Attach them to the anterior nasal spine and the pyriform aperture on each side. Use the remaining cartilage for onlay grafts to augment the nasal tip.

Lining defects of the nasal tip are unusual because of its midline location. However, if they occur, anteriorly based septal mucosal flaps can be rotated in to provide coverage.

Case 3 (see images below):

Case 3. Intraoperative design of a paramedian forehead flap for a full-thickness skin defect of the nasal tip and lower dorsum.

Case 3. Intraoperative design of a paramedian forehead flap for a full-thickness skin defect of the nasal tip and lower dorsum.

Case 3. Intraoperative basal view demonstrating planned enlargement of the nasal defect (hatched area) to encompass the aesthetic subunit of the nasal tip.

Case 3. Intraoperative basal view demonstrating planned enlargement of the nasal defect (hatched area) to encompass the aesthetic subunit of the nasal tip.

Case 3. Postoperative result at 1 year. Note that the flap has replaced the skin of the tip and dorsum of the nose.

Case 3. Postoperative result at 1 year. Note that the flap has replaced the skin of the tip and dorsum of the nose.

Case 3. Postoperative result. Note placement of the scars at the borders of the columella and alar lobules.

Case 3. Postoperative result. Note placement of the scars at the borders of the columella and alar lobules.

This patient presented after excision of a melanoma with a 15- X 20-mm defect of the nasal tip and dorsum. The alar cartilages were exposed but intact. His nose was reconstructed with a forehead flap, replacing the complete nasal tip and dorsum. He is shown 1 year after surgery.

Alar lobule

The management of this portion of the nose depends on both the size and depth of the defect. As discussed previously, the skin and underlying soft tissues of the alar lobule form a semirigid unit that helps form the graceful curve of the alar rim and provides patency to the anterior nares. If most of this soft tissue is missing, it is evident because it collapses. In such patients, provide support with a conchal cartilage graft taken just inside the antihelix where it has the greatest curve and rigidity.

Skin replacement for defects confined to the alar lobule can be covered with a bilobed flap based medially. If the entire lobule is missing, it may be necessary to leave the donor site of the second lobe of the flap partially open. It closes in 2-4 weeks, and the scar can be revised later, although it seldom is necessary. An alternative is a 2-stage superiorly based nasolabial flap.

If the defect of the alar lobule also involves the lateral wall of the nose, it can be closed with either a superiorly based nasolabial flap or a forehead flap. If the cheek skin is thin and atrophic, choose a nasolabial flap. Otherwise, select a forehead flap, because its skin thickness is a superior match.

Lining deficiencies of the alar lobule can be resurfaced with a bipedicled mucosal advancement flap taken from inside the lateral wall of the nose. Larger defects require an anteriorly based septal mucosal flap.

Case 4 (see images below):

Case 4. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12- X 15-mm full-thickness defect of the nasal tip and ala with loss of the lateral crura, shown prior to the insertion of a conchal cartilage graft.

Case 4. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12- X 15-mm full-thickness defect of the nasal tip and ala with loss of the lateral crura, shown prior to the insertion of a conchal cartilage graft.

This patient presented with a 12- X 15-mm full-thickness defect of the medial alar lobule and lateral wall of the nose down to the lining with collapse of the anterior nares. Her nose was reconstructed with a conchal cartilage graft for support and a medially based bilobed flap. The donor site could not be closed primarily; therefore, a 5-mm wound was left to heal by secondary intention. She is shown 4 months after surgery without any revisions.

Case 5 (see images below):

Case 5. Intraoperative design of superiorly based nasolabial flap for complete loss of the alar lobule. The lining and skeleton have been reconstructed with a bipedicled mucosal flap and a conchal cartilage graft.

Case 5. Intraoperative design of superiorly based nasolabial flap for complete loss of the alar lobule. The lining and skeleton have been reconstructed with a bipedicled mucosal flap and a conchal cartilage graft.

Case 5. Preoperative nasal defect and early postoperative result at 2 weeks after division and inset of the flap. Note the hyperpigmentation of the flap, which can be treated with a laser if it does not resolve.

Case 5. Preoperative nasal defect and early postoperative result at 2 weeks after division and inset of the flap. Note the hyperpigmentation of the flap, which can be treated with a laser if it does not resolve.

This patient presented 1 year after losing the entire alar lobule as a result of a necrotizing staphylococcal skin infection. It was reconstructed with a bipedicled mucosal advancement flap for lining, a conchal cartilage graft, and a 2-stage superiorly based nasolabial flap. He is shown in the acute phase, 2 weeks after division and inset of the flap. Note the hyperpigmentation of the flap, which in most patients resolves over time. If hyperpigmentation persists, it can be lightened with an Nd:YAG laser.

A study by Lindsay and Morton indicated that following the excision of a small, penetrating basal cell carcinoma from the region of the nose just medial to the nasofacial groove (a common site for this type of cancer), the resulting defect can be effectively repaired by combining a subcutaneous fat transposition flap from adjacent cheek fat with a full-thickness skin graft. The investigators found that use of the fat flap/skin graft combination can avoid the facial asymmetry and pin cushioning effect that, Lindsay and Morton state, a single-stage nasolabial transposition flap can cause. The study involved 21 patients who underwent the combination procedure, with no hematomas, postoperative infections, or graft failures occurring. [19]

Heminasal and total nasal reconstruction

Reconstruction of the more extensive heminasal or total nasal defect is an extension of the principles applied to loss of the regional aesthetic subunits.

Replacement of the skin layer is accomplished with the forehead flap. If forehead skin is unavailable, alternatives include the Washio postauricular flap (an article was published on it in 1969) or the Tagliacozzi flap. [20, 2] Replace the nasal skeleton using a rib graft for the nasal dorsum and lateral nasal wall. Use septal and conchal cartilage grafts as described for the nasal tip and alar lobules.

The lining of the distal two thirds of the nose can be covered with anteriorly based septal mucosal flaps. However, if bilateral septal flaps are used, the septal cartilage becomes devascularized, resulting in an iatrogenic septal perforation. If the defect is beyond the reach of septal mucosal flaps, alternatives include an inferiorly based pericranial flap from the frontal bone or a temporoparietal fascia free flap. These flaps then can be lined with strips of free mucosal grafts.

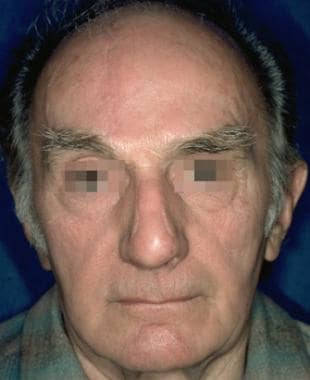

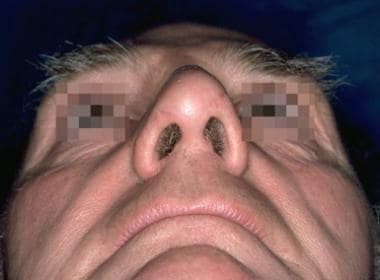

Case 6 (see images below):

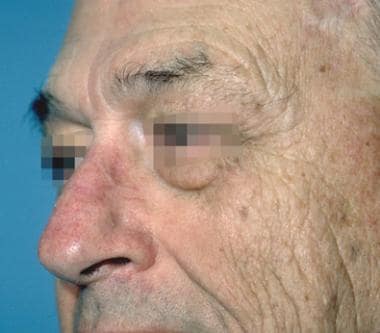

Case 6. Postoperative result 1 year after reconstruction of heminasal defect with a septal mucosal flap, rib bone and conchal cartilage grafts, and a paramedian forehead flap.

Case 6. Postoperative result 1 year after reconstruction of heminasal defect with a septal mucosal flap, rib bone and conchal cartilage grafts, and a paramedian forehead flap.

This patient presented with a neglected basal cell carcinoma; after Mohs excision, he was left with a heminasal defect involving all layers of the nose. His nose was reconstructed with an anteriorly based septal mucosal flap for lining, a rib bone and cartilage graft for the lateral nasal wall, a conchal cartilage graft for the alar lobule, and a 2-stage forehead flap for the skin layer. He is shown 1 year after surgery. Mahlberg et al treated patients who had undergone Mohs surgery with a spiral flap. They concluded that this is a reproducible, one-stage flap for small to medium-sized defects of the nasal ala and alar groove that consistently produces topographic restoration with minimal risk of aesthetic or functional complication. [21]

Case 7 (see images below):

This patient presented after excision of a basal cell carcinoma with a subtotal nasal defect including loss of portions of the alar cartilages and cartilaginous dorsum. Her nose was reconstructed with conchal cartilage onlay grafts and a 2-stage forehead flap. She is shown 6 months after surgery.

-

Nasal aesthetic subunits.

-

Nasal skeleton.

-

Bilobed flap. The flap is designed with the long axis of the defect, and each lobe of the flap is separated by 45° angles. The two lobes of the flap rotate along a perfect arc with all points on the arc equidistant from the apex of the defect.

-

Nasolabial flap. The base of the pedicle of this flap lies on the lateral nasal wall and is transposed a maximum of 60° to avoid a "bridge" effect of the flap crossing the nasofacial angle.

-

Paramedian forehead flap. This flap is designed using a foil template of the defect. Its pedicle is centered on the Doppler signal of the supraorbital artery, and the distal one half of the flap is thinned down to the subdermal plexus.

-

Septal mucosal flap. This anteriorly based flap is cut as wide as possible and released with a low posterior back cut only as needed to turn the flap into the defect.

-

Case 1. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 1. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12-mm full-thickness skin defect of the nasal dorsum.

-

Case 1. Postoperative result at 9 months.

-

Case 1. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 1. Postoperative result at 9 months.

-

Case 2. Intraoperative design of a superiorly based nasolabial flap for a full-thickness skin defect involving portions of the tip, ala, and lateral wall of the nose.

-

Case 2. Intraoperative result after inset of the flap and closure of the donor site.

-

Case 2. Postoperative result at 6 months.

-

Case 3. Intraoperative design of a paramedian forehead flap for a full-thickness skin defect of the nasal tip and lower dorsum.

-

Case 3. Intraoperative basal view demonstrating planned enlargement of the nasal defect (hatched area) to encompass the aesthetic subunit of the nasal tip.

-

Case 3. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 3. Postoperative result at 1 year. Note that the flap has replaced the skin of the tip and dorsum of the nose.

-

Case 3. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 3. Postoperative result at 1 year.

-

Case 3. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 3. Postoperative result. Note placement of the scars at the borders of the columella and alar lobules.

-

Case 4. Intraoperative design of a bilobed flap for a 12- X 15-mm full-thickness defect of the nasal tip and ala with loss of the lateral crura, shown prior to the insertion of a conchal cartilage graft.

-

Case 4. Preoperative nasal defect.

-

Case 4. Postoperative result at 6 months.

-

Case 5. Intraoperative design of superiorly based nasolabial flap for complete loss of the alar lobule. The lining and skeleton have been reconstructed with a bipedicled mucosal flap and a conchal cartilage graft.

-

Case 5. Intraoperative result after inset of the flap and closure of the donor site.

-

Case 5. Preoperative nasal defect showing complete loss of the alar lobule.

-

Case 5. Early postoperative result at 2 weeks after division and inset of the flap.

-

Case 5. Preoperative nasal defect and early postoperative result at 2 weeks after division and inset of the flap. Note the hyperpigmentation of the flap, which can be treated with a laser if it does not resolve.

-

Case 6. Nodular basal cell carcinoma of the nose.

-

Case 6. Intraoperative view of heminasal defect with loss of skin, skeleton, and lining.

-

Case 6. Nodular basal cell carcinoma of the nose.

-

Case 6. Postoperative result 1 year after reconstruction of heminasal defect with a septal mucosal flap, rib bone and conchal cartilage grafts, and a paramedian forehead flap.

-

Case 7. Preoperative view of subtotal nasal skin defect.

-

Case 7. Postoperative result at 1 year after reconstruction with a paramedian forehead flap.