Practice Essentials

Hepatoblastoma is the most common form of liver cancer in children, although it is a comparatively uncommon pediatric solid tumor. (See the image below.) The disease usually affects children younger than 3 years. Surgical techniques and adjuvant chemotherapy have markedly improved the prognosis of patients with hepatoblastoma. [1]

Signs and symptoms

Hepatoblastoma is usually diagnosed as an asymptomatic abdominal mass. Patients may also display the following:

-

Hemihyperplasia: An incidental finding in approximately 10% of patients

-

Isosexual precocity: Penile and testicular enlargement without pubic hair is seen in patients with tumors that secrete the β subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG).

-

Late features of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS): Rare; include midface hypoplasia and slitlike indentations of the earlobe

-

Anorexia: In advanced disease

-

Talipes equinovarus

-

Persistent ductus arteriosus

-

Tetralogy of Fallot

-

Extrahepatic biliary atresia

-

Renal anomalies (dysplastic kidney, horseshoe kidney)

-

Cleft palate

-

Dysplasia of the earlobes

-

Goldenhar syndrome

-

Prader-Willi syndrome

-

Meckel diverticulum

-

Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome

-

Sotto Syndrome

-

Symptoms associated with osteopenia: Severe osteopenia is present in most patients, but, with the exception of pathologic fracture, symptoms are rare

-

Symptoms of acute abdomen: Rare; occur if the tumor ruptures

-

Severe anemia: Occurs occasionally, as a result of tumor rupture and hemorrhage

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Laboratory studies

-

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential: Normochromic normocytic anemia and thrombocytosis may be present

-

Liver enzyme levels: Moderately elevated in 15-30% of patients

-

α-fetoprotein (AFP): Levels in hepatoblastoma are often as high as 100,000-300,000 mcg/mL

Imaging studies

-

Radiography: Reveals mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen

-

Ultrasonography: Allows assessment of tumor size and anatomy

-

Computed tomography (CT) scanning: Reveals involvement of nearby structures and whether pulmonary metastases are present

-

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Believed to be superior to CT scanning but does not necessarily add to the anatomic detail seen on CT scans

-

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning: May have a role in diagnosis and follow-up evaluation

-

Radionuclide bone scanning: To evaluate for bone metastases in symptomatic patients

Biopsy

Surgical resection is the usual manner in which material for pathologic assessment is obtained. Open biopsy is performed when complete surgical resection is not possible. Needle biopsy is not recommended, because hepatoblastomas usually are highly vascular.

Staging

-

Stage I: Tumor is completely resectable via wedge resection or lobectomy; tumor has pure fetal histologic (PFH) results; AFP level is within reference range within 4 weeks of surgery

-

Stage IIA: Tumor is completely resectable; tumor has histologic results other than PFH (unfavorable histology [UH])

-

Stage IIB: Tumor is completely resectable; AFP findings are negative at time of diagnosis (ie, no marker to follow)

-

Stage IIC: Tumor is completely resected or is rendered completely resectable by initial radiotherapy or chemotherapy or microscopic residual disease is present; AFP level is elevated 4 weeks after resection

-

Stage III (any of the following): Either the tumor is initially unresectable but is confined to 1 lobe of the liver, gross residual disease is present after surgery, the tumor ruptures or spills preoperatively or intraoperatively, or regional lymph nodes are involved

-

Stage IV: Distant bone or lung metastasis has occurred

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Chemotherapy

-

Cisplatin is the most active single agent used to treat hepatoblastoma

-

The cisplatin/5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/vincristine (VCR) combination is regarded as standard chemotherapeutic treatment in hepatoblastoma

-

Preoperative chemotherapy can completely eradicate metastatic pulmonary disease and multinodular liver disease

-

Postoperatively, chemotherapy is usually started approximately 4 weeks after surgery to allow liver regeneration

Radiotherapy

-

Doses used for treatment of hepatoblastoma are usually 1200-2000 centigray (cGy)

-

Radiotherapy may be used when microscopic disease is seen at the resection margins

-

Adjuvant radiotherapy may have a role in the treatment of chemoresistant pulmonary metastases

Resection and transplantation

-

Lobectomy: Initial resection of operable primary tumors by lobectomy is the standard of care in hepatoblastoma

-

Liver transplantation: Has had an increasing role in children with nonresectable tumors or in those who show chemotherapy resistance

-

Thoracotomy and resection of pulmonary metastases: Some patients have long-term, disease-free survival when aggressive attempts are made to surgically eradicate all areas of disease

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Hepatoblastoma is the most common liver cancer in children, although it is relatively uncommon compared with other solid tumors in the pediatric age group. Over the past several years, pathologic variations of hepatoblastoma have been identified, and techniques for establishing the diagnosis of childhood hepatic tumors have improved. Surgical techniques and adjuvant chemotherapy have markedly improved the prognosis of children with hepatoblastoma. Complete surgical resection of the tumor at diagnosis, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, is associated with 100% survival rates, but the outlook remains poor in children with residual disease after initial resection, even if they receive aggressive adjuvant therapy.

Considerable controversy has surrounded the discrepancy between US and international hepatoblastoma therapeutic protocols; surgery and staging are initially advised in the United States, whereas adjuvant therapy is strongly considered internationally. Significant data now support a role for preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy if the tumor is inoperable or if the tumor is unlikely to achieve gross total resection at initial diagnosis. [2] Early involvement of hepatologists and liver transplant teams is recommended if the tumor may not be completely resectable even with preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Liver transplantation is playing an increasing role in cases in which the tumor is deemed nonresectable after chemotherapy is administered or in "rescue" transplantation when initial surgery and chemotherapy are not successful. [3, 4]

Finally, reports state that aggressive surgical intervention may be warranted for isolated pulmonary metastases. [2, 5]

Pathophysiology

Hepatoblastomas originate from immature liver precursor cells and present morphologic features that mimic normal liver development. Hepatoblastomas are usually unifocal and affect the right lobe of the liver more often than the left lobe. Microvascular spread can extend beyond the apparently encapsulated tumor.

Grossly, the tumor is a tan bulging mass with a pseudocapsule. Cirrhosis is not associated with this tumor. Metastases affect the lungs and the porta hepatis; bone metastases are very rare. CNS involvement has been reported at diagnosis and during relapse. The identification of distinct subtypes and further molecular biological information derived regarding liver ontogenesis and growth regulation of hepatic tumors has recently helped pave the way for a more comprehensive classification system for this disease.

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome arm 11p markers occurs commonly in hepatoblastoma identified in association with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) and hemihypertrophy. Isochromosome 8q is seen in mixed hepatoblastomas, and trisomy 20 is seen in pure epithelial hepatoblastomas (see Histologic Findings).

Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), a syndrome of early-onset colonic polyps and adenocarcinoma, frequently develop hepatoblastomas. Germline mutations in the APC tumor suppressor gene occur in patients with FAP, and mutations in the APC tumor suppressor gene are frequently detected in the colonic polyps and adenocarcinomas associated with FAP. One study estimated that 1 in 20 hepatoblastomas is probably associated with FAP. [6] Interestingly, APC mutations, although common in patients with hepatoblastoma and FAP, are rare in patients with sporadic hepatoblastomas. Sanders and Furman reported 2 brothers with hepatoblastoma who had a significant family history of early onset colon cancer. [7] Testing of the younger brother revealed a deletion in exon 15 of the APC gene consistent with a diagnosis of FAP.

In a study of 29 tumors from children with sporadic hepatoblastoma, no germline APC mutations were found. [8] These authors conclude that routine APC screening does not need to be performed in these children without a family history of colorectal cancer or FAP.

Loss of function mutations in APC lead to intracellular accumulation of the protooncogene β-catenin, an effector of Wnt signal transduction. β-Catenin mutations have been shown to be common in sporadic hepatoblastomas, occurring in as many as 67% of patients. Furthermore, a study in a mouse model of hepatoblastomas induced by toxin exposure detected mutations of the β-catenin protooncogene in 100% of the tumors analyzed (27 of 27). [9] This finding suggests that alterations in the Wnt signaling pathway likely contribute to the neoplastic process in this particular tumor.

More recent studies on other components of the Wnt signaling pathway have also demonstrated a likely role for constitutive activation of this pathway in the etiology of hepatoblastoma. [10, 11] Overexpression of human Dickkopf-1, a known antagonist of the Wnt pathway, has been found in hepatoblastoma. The authors postulate that this may be a direct negative feedback mechanism resulting from increased β-catenin commonly found in this tumor. [12]

A mutation in the axin gene, also a known antagonist of β-catenin accumulation, has been found in hepatoblastoma and may contribute to the etiology of the smaller percentage of hepatoblastomas in which β-catenin mutations have not been identified, thus implicating the constitutive activation of the Wnt pathway in a significant fraction of hepatoblastomas. [13, 14] Kuroda et al demonstrated a potential role for transcriptional targeting of tumors with strong β-catenin/T-cell factor activity with oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector. [15] The hedgehog (Hh) pathway has also been evaluated and has been found to be a potential therapeutic target for hepatoblastomas in which the Hh pathway is overexpressed or reactivated at an inappropriate time. [16]

Blocking the Hh pathway with the antagonist cyclonamine has shown a strong inhibitory effect on hepatoblastoma cell line proliferation. A high frequency of glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (GLI1) and patched homolog 1 (PTCH1) overexpression and Hh-interacting protein (HHIP) promoter methylation is noted in early childhood hepatoblastoma, which also supports a key role for Hh signalling activation in malignant transformation of embryonal liver cells. [17]

Wnt pathway activation appears to be more prevalent in embryonal and mixed subtypes of hepatoblastoma, whereas notch pathway activation is more prevalent with the more differentiated pure fetal hepatoblastoma tumors. [18] The relative activation of Hh, Wnt, and notched signaling pathways appears to be useful in stratification of different subtypes.

Increasing evidence suggests that hepatoblastoma is derived from a pluripotent stem cell. [19] This further supports the hypothesis that this tumor arises from a developmental error during hepatogenesis and supports the hypothesis that research particularly focused on these developmental processes governing liver maturation and growth may ultimately lead to more effective targeted therapy for this disease.

Etiology

As with other pediatric malignancies, the cause of hepatoblastoma is generally unknown. Cancer has been postulated to arise from unregulated cellular differentiation and proliferation. Similarities between the developing fetal liver and the fetal epithelial-type cells of hepatoblastoma are striking. Developing cells of the early fetal liver and the cells of fetal hepatoblastoma are similar in size and configuration. A developmental disturbance during liver formation in embryogenesis likely results in aberrant proliferation of these undifferentiated cells.

Increasing data support a role for aberrant transduction of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and its molecular targets in hepatoblastoma tumorigenesis. Research in this area may ultimately contribute not only toward a better understanding of this malignant neoplasm but may also lead to more specific molecular-targeted therapies.

Hepatoblastoma, like Wilms tumor, is associated with BWS and hemihypertrophy, suggesting gestational oncogenic events. Persons with dysplastic kidney or Meckel diverticulum have a higher incidence of this tumor. Hepatoblastoma has also been reported to be associated with maternal oral contraceptive exposure, fetal alcohol syndrome, and gestational exposure to gonadotropins.

Studies performed in Europe suggest an association between low birth weight (LBW), very low birth weight (VLBW), and prematurity and hepatoblastoma. The suspected correlation between LBW, prematurity (< 1000 g), and hepatoblastoma has been confirmed in both the United States and Japan. [20, 21]

Patients with FAP have a significantly increased incidence of hepatoblastoma and should therefore be screened in early childhood with AFP measurements.

A child with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) who developed hepatoblastoma was reported. [22] Hepatoblastoma has also been reported in association with other cancer predisposition syndromes including FAP, BWS, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, trisomy 18, and glycogen storage disorders.

A large population-based study found an increased risk of hepatoblastoma in children with several forms of nonchromosomal congenital heart disease. The study also confirmed an association seen in earlier trials between hepatoblastoma and trisomy 18. [23]

Premature infants, particularly those with LBW or VLBW, are at significantly increased risk of developing hepatoblastoma. The presence of erythropoietin receptors in hepatoblastomas has been postulated to potentially contribute to this increased incidence because many premature infants with LBW or VLBW receive this medication during their time in neonatal intensive care.

Increasing evidence suggests that exposure to carcinogenic agents such as bromochloroacetic acid may be tumorigenic. [24]

Epidemiology

United States data

Hepatoblastoma accounts for 79% of all liver tumors in children and almost two thirds of primary malignant liver tumors in the pediatric age group. Approximately 100 cases of hepatoblastoma are reported per year. The annual incidence of hepatoblastoma in infants younger than 1 year is 11.2 cases per million; in 1990-1995, the annual incidence in children overall was 1.5 cases per million, which is almost double the incidence from 1975-1979.

A significantly higher rate of hepatoblastomas is observed among low birth weight (LBW) and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants born prematurely. [25]

A Children’s Oncology Group (COG) protocol (AEP104C1) is currently investigating exogenous and endogenous causes for the increase in incidence and potential cause of premature births. The study is also exploring potential effectors independent of prematurity and LBW or VLBW. All children with hepatoblastoma diagnosed before age 6 years from 2000-2005 are eligible for retrospective analysis, and prospective analysis will be performed for children diagnosed between June 2005 and December 31, 2008. This is the largest, most comprehensive case-control study of hepatoblastoma performed thus far.

International data

In Japan, efforts to improve vaccination rates have led to decreases in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and, to a lesser degree, in hepatoblastoma. Carcinogen exposure in some developing countries is linked to hepatoblastoma and HCC.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

White children are affected almost 5 times more frequently than Black children. Black patients tend to have worse outcomes.

Males are typically affected more frequently than females; the male-to-female ratio is 1.7:1. Male-to-female ratios are somewhat higher in Europe (1.6-3.3:1) and Taiwan (2.9:1).

Hepatoblastoma usually affects children younger than 3 years, and the median age at diagnosis is 1 year. Hepatoblastoma is very rarely diagnosed in adolescence and is exceedingly rare in adults. Occasionally, nests of hepatoblastoma cells are found in hepatocellular carcinoma lesions; this is more common in adults than in children. Older children and adults tend to have a worse prognosis.

Prognosis

A study by O’Neill et al looked to determine whether the pattern of lung nodules in thirty-two patients with metastatic hepatoblastoma treated with vincristine and irinotecan (VI) correlates with outcome. The study reported that 31% of the patients met Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) for measurable metastatic disease. Increased risks for an event-free- survival event were associated with the presence of measurable disease by RECIST, the sum of nodule diameters greater than or equal to the cumulative cohort median size, bilateral disease, and ≥ 10 nodules. [26]

Morbidity/mortality

A large multicenter COG study included 182 children with hepatoblastoma diagnosed between August 1989 and December 1992. [27] Of these, 9 had stage I disease with favorable histology (FH), 43 had stage I with unfavorable histology (UH), 7 had stage II, 83 had stage III, and 40 had stage IV disease (see Staging).

All 9 patients with stage I and FH received treatment with low-dose doxorubicin and were alive and free of disease. Overall survival rates for all stages 5 years after treatment were 57-69%. The 5-year event-free survival (EFS) rates were 91% for patients with stage I with UH, 100% for stage II, 64% for stage III, and 25% for stage IV.

In general, patients who undergo complete resection of the tumor and adjuvant chemotherapy have a survival rate of 100%. Patients with favorable histology and low mitotic rate with complete resection may not require chemotherapy; for this reason, US protocols have advocated for formal staging and pathologic diagnosis prior to administering any adjuvant chemotherapy.

More recently, data from the International Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group (SIOPEL), which used preoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, demonstrated overall survival rates as high as 89% and event-free survival rates as high as 80%. [28] Australian investigators demonstrated that patients treated between 1984 and 2004 also had excellent outcomes, provided surgical margins were clear. [2] No correlation between α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and outcome was reported in the study.

Other morbidity can result from precancerous medical conditions, operative complications, or toxic effects of chemotherapy. Short- and long-term sequelae and toxic effects of surgical management and chemotherapy are discussed below (see Surgical Care and Medical Care).

Complications

Tumor rupture may occur at diagnosis, resulting in acute abdomen or severe hemorrhage, both of which constitute medical emergencies. Intraoperative and postoperative complications may occur as a result of resection or biopsy procedures.

Complications can develop with the administration of chemotherapy. Myelosuppression and immunosuppression place the patient at risk for bleeding and infection. After several cycles of therapy, organ toxicity may occur; for example, renal function or hearing may be impaired.

Posttransplantion complications can develop and require close long-term follow-up by the liver transplant team.

Particular attention must be paid to cardiac, renal, and hearing status to assess for the long-term toxic effects of anthracyclines, cisplatin, or carboplatin. One of the most important adverse effects of platinum chemotherapy is hearing loss. A Cochrane Database review of 3 studies that evaluated the use of the chemoprotective agent amifostine versus no additional treatment did not come to any definitive conclusions. Further research is needed regarding the usefulness of possible drugs to prevent hearing loss in children treated with platinum chemotherapy. [29]

Psychosocial effects of frequent painful procedures, hospitalizations, and interference with normal childhood growth and development must be addressed, and children and families must be referred to appropriate specialists when needed. The family's psychosocial needs are affected greatly by having a child with cancer.

Patient Education

Medications

To ensure compliance and good medical care, patient and family understanding regarding the importance of treatment and the toxic effects of the medications is critical. In addition, patients and their families should learn to recognize and identify signs and symptoms of complications that require urgent medical care.

Long-term follow-up surveillance

After completion of therapy, patients in whom treatment was successful require close surveillance for any signs or symptoms of recurrent disease. Follow-up care includes monitoring AFP levels, physical examination, and diagnostic imaging. Because most recurrences occur during the first 2 years following treatment, most protocols recommend close follow-up monitoring during this interval. Hepatoblastoma does not usually recur more than 3 years after completion of therapy.

Long-term issues

Growth and development and long-term toxic effects on organs are long-term issues. Patients who remain free of recurrent disease for 5 years are considered cured; long-term follow-up monitoring to assess the impact of therapy on growth, development, and organ toxicity is essential. Patients are usually monitored by pediatric oncologists, but some sequelae may require the involvement of other subspecialist health care providers.

Other issues

Most centers have late effects clinics, and all children treated for cancer should continue to see their oncology providers regularly to monitor for potential long-term complications of therapy. When appropriate, most centers help transition to an adult provider, with guidelines on what to watch for and which tests should be performed to monitor for potential late effects. A cancer-preventive lifestyle is encouraged and includes avoiding passive or primary tobacco exposure, wearing sunscreen, healthy eating habits, maintaining a healthy weight, and an exercise regimen.

-

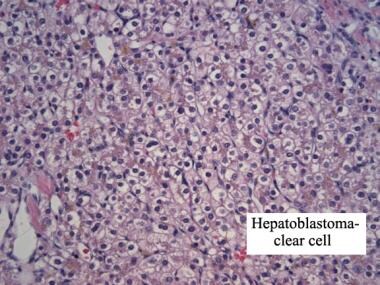

Clear cell hepatoblastoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Image courtesy of Denise Malicki, MD.

-

Embryonal hepatoblastoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Image courtesy of Denise Malicki, MD.

-

Fetal components of hepatoblastoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Image courtesy of Denise Malicki, MD.

-

Hepatoblastoma. Normal liver tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Image courtesy of Denise Malicki, MD.