Practice Essentials

Infectious mononucleosis is a clinical syndrome caused mostly by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), or human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), which is a γ-herpesvirus. [1] EBV is widely disseminated; it is spread by intimate contact between asymptomatic EBV-infected persons who shed the virus and susceptible persons.

The most common manifestation of primary infection with EBV is acute infectious mononucleosis, which is a self-limiting clinical syndrome that most frequently affects adolescents and young adults. Classic symptoms include malaise, fever, sore throat, fatigue, and generalized adenopathy. Infectious mononucleosis is characterized by atypical-appearing mononuclear lymphocytes. It was known synonymously as "Drüsenfieber," or glandular fever, owing to pronounced generalized lymphadenopathy.

EBV is the first human virus confirmed to be an oncovirus and may give rise to various lymphoproliferative malignancies in immunocompromised hosts. It is associated with various tumors, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, lymphoreticular malignancies, and Burkitt lymphoma. [2, 3]

EBV causes 90% of cases of infectious mononucleosis. Primary infection with cytomegalovirus, Toxoplasma gondii, adenovirus, viral hepatitis, HIV, and rubella virus causes an infectious mononucleosis-like illness. The exact cause remains unknown in the majority of cases of EBV-negative infectious mononucleosis.

Acute infectious mononucleosis was first described in 1889 as acute glandular fever, an illness characterized by lymphadenopathy, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, malaise, and abdominal discomfort in adolescents and young adults. In 1920, Sprunt and associates applied the name infectious mononucleosis to cases of spontaneously resolving acute leukemia associated with blast-like cells in the blood. The distinctive mononuclear lymphocyte cell associated with EBV is known as a "Downey cell," after Hal Downey, who contributed to the characterization of it in 1923. In 1932, Paul and Bunnell discovered that serum from symptomatic patients had antibodies that agglutinate the red blood cells (RBCs) of unrelated species, the "heterophile antibodies." This finding allowed enhanced diagnostic accuracy of infectious mononucleosis, even if the exact virus had not been isolated.

In 1958, Denis Burkitt, who was a surgeon posted in Uganda during World War II, reported a specific type of cancer that was common in young children living across central Africa. These aggressive tumors – later named after him as Burkitt lymphoma – were caused by white blood cells multiplying out of control. Later in 1964, UK researcher Antony Epstein and his colleagues Yvonne Barr and Burt Achong collaborated with Denis Burkitt and looked at the Burkitt lymphoma cells from tumor specimens shipped from Uganda. They detected tiny virus particles under the electron microscope in those specimens. In 1965, the newly discovered first human oncovirus was named Epstein-Barr virus. [4]

The EBV DNA was fully sequenced in 1984.

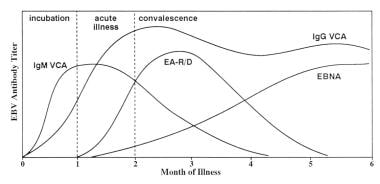

The graph below demonstrates the antibody response to Epstein-Barr virus.

Infectious mononucleosis. Antibody response to Epstein-Barr virus. Adapted with permission from Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Epstein-Barr virus serology. Infect Dis Pract. 1995;19:26-27.

Infectious mononucleosis. Antibody response to Epstein-Barr virus. Adapted with permission from Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Epstein-Barr virus serology. Infect Dis Pract. 1995;19:26-27.

The search for the etiologic agent of infectious mononucleosis was unsuccessful for many years, partly because researchers did not appreciate that most primary infections are asymptomatic and that most adults are seropositive. In 1964, Epstein described the first human tumor virus when he found virus particles in a Burkitt lymphoma cell line. [5] Henle et al reported the relationship between acute infectious mononucleosis and EBV in 1968. [6] Subsequently, a large prospective study of students at Yale University firmly established EBV as the etiologic agent of infectious mononucleosis. [7]

Background

EBV is a double-stranded DNA virus with an envelope and is a member of the gammaherpes virus family (HHV-4). Types 1 and 2 are two distinct types of EBV (type A and B). Although previous studies suggested that EBV-1 (type A) virus infection was more prevalent in North America and Europe and that EBV-2 (type B) virus infection was more prevalent in Africa, more recent studies suggest that both strains are prevalent in the United States. [8]

The differences between the strains are due to the altered sequence of viral genes expressed during latent infection, which differ in their ability to transform B cells. EBV infection causes lifelong, persistent latent infection. No clinical differences have been identified between the two types. In immunocompromised persons, dual infections with two types have been documented, even though no much type-specific clinical manifestations have been noted.

EBV infects >95% of the world population. Infection with this virus in developing countries and among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations of developed countries usually occurs during infancy and early childhood. Primary infection during childhood is typically not apparent or is indistinguishable from other common childhood infections. In developing countries, EBV infection occurs early in life. Nearly the entire population of a developing country becomes infected before adolescence. Thus, symptomatic infectious mononucleosis is uncommon in such countries.

In adolescents and young adults, the primary EBV infection manifests in >50% of cases as the classic triad of fatigue, pharyngitis, and generalized lymphadenopathy. This syndrome is rarely apparent in children younger than 4 years of age or in adults older than 40 years, even though most of these individuals have already been infected by EBV. Infants and children younger than 4 years handle the virus better than adults. Once infected, EBV persists in the memory B-cell pool of healthy individuals, and any disruption of this interaction results in virus-associated B-cell tumors.

The association of EBV with epithelial cell tumors, specifically nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) and EBV-positive gastric carcinoma (EBV-GC), is less clear and is currently thought to be caused by the aberrant establishment of virus latency in epithelial cells that display premalignant genetic changes. [9]

In areas with high standards of hygiene, such as the United States and western Europe, EBV infection may be delayed until adulthood and the incidence of infectious mononucleosis is higher than in developing countries. Generally, however, the incidence of infectious mononucleosis is showing a decreasing trend worldwide in the past decade. [10]

Pathophysiology

Primates are the only known reservoir of EBV.

EBV has lytic and latent life cycles. Primary infection with EBV is followed by latent infection, a characteristic of all herpesviruses.

EBV is present in oropharyngeal secretions and is most commonly transmitted through saliva. Usually EBV is shed in oral secretions by 20-30% of immunocompetent individuals and about 60-90% of immunosuppressed patients for >6 months after an acute infection and then intermittently for life.

The virus is transmitted through oral secretions, as occurs in "deep kissing" in adolescents or young adults, or by sharing water bottles and toys among children in preschool care areas. It has been suspected to be transmitted via penetrative sexual intercourse, because virus particles infect cervical mucosa in females, but confirmed reports of this mode of spreading are not available. [11] EBV is found in both female and male genital secretions in a lesser number compared with the presence of virus in saliva, especially type 2 virus.

Usually fomites and non-intimate contacts, such as living in same room, or environmental sources seldom contribute to the spread of EBV. Hence, outbreaks of infectious mononucleosis seldom occur. The virus can be transmitted to susceptible recipients by blood transfusion, [12] solid organ transplantation, and hematopoietic cell transplantation. [13]

The reason for the prolonged incubation period for infectious mononucleosis is still unclear.

After initial inoculation, the virus replicates in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Cell lysis is associated with release of virions, with viral spread to contiguous structures, including salivary glands and oropharyngeal lymphoid tissues. During primary infection, viral replication is first detected in the oral cavity. EBV infects epithelial cells in tonsillar crypts and B cells in the parenchyma of the tonsil. It has been shown that virus derived from epithelial cells has a much higher entry efficiency for infecting B cells.

Further viral replication results in viremia and subsequently infection of the lymphoreticular system, including the liver, spleen, and B lymphocytes in peripheral blood. A rapid cellular response by T cells is crucial for suppression of the primary EBV infection and determines the clinical expression of the infection.

Symptomatic primary infection with EBV is usually followed by a latent stage. After acute EBV infection, latently infected lymphocytes and epithelial cells persist and are immortalized. In vivo, this allows perpetuation of infection, while, in vitro, immortalized cell lines are established. The latent infection is established by self-replicating extra-chromosomal nucleic acid, the episomes. During latency, infected B-lymphocytes are immortalized by the virus, which leads to a state of polyclonal activation to form continuous cell lines. [14]

Host immune response to the viral infection includes CD8+ T lymphocytes with suppressor and cytotoxic functions, the characteristic atypical lymphocytes found in the peripheral blood. The T lymphocytes are cytotoxic to the EBV-infected B cells and eventually reduce the number of EBV-infected B lymphocytes. In persons with an intact cellular immune response, the infection is controlled by cytotoxic T cells. The main reservoir for EBV reactivation and development of EBV-related malignancies is the memory-B cells.

Two strains, labeled EBV-1 and EBV-2 (also known as type A and type B), have been identified. Although the genes expressed during latent infection have some differences, the acute illnesses caused by the two strains are apparently identical. Both strains are prevalent throughout the world and can simultaneously infect the same person.

It is essential to know the structure of EBV and which proteins are expressed during different stages of its life cycle to understand the laboratory tests used to determine whether a patient has primary acute, convalescent, latent, or reactivation infection. EBV glycoprotein gp350 is important for attachment of the virus to B cells. [15] Most prophylactic EBV vaccines have used gp350.

A mature infectious viral particle, which may be present in the cytoplasm of an epithelial cell, consists of a nucleoid, a capsid, and an envelope. The nucleoid contains linear double-stranded viral DNA. It is surrounded by the capsid. An envelope derived from the outer membrane or the nuclear membrane of the host cell encloses the capsid and nucleoid (ie, the nucleocapsid). The envelope also contains viral proteins that were constructed and placed in the host cell membrane before viral assembly began.

Antibodies produced in response to infection are directed against EBV structural proteins, such as viral capsid antigens (VCAs), early antigens (EAs), and EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA). These antibodies are used for the serologic diagnosis of EBV infection. In a healthy EBV-seropositive adult, approximately 0.005% of circulating B cells are infected with EBV. [16]

The receptor for the virus on epithelial cells and B lymphocytes is the CD21 molecule. To initiate cellular infection, a viral particle attaches via its major outer envelope glycoprotein to the EBV receptor CD21 on a B lymphocyte. EBV is then internalized into cytoplasmic vesicles. After fusion of the virus envelope with the vesicle membrane, the nucleocapsid is released into the cytoplasm. The nucleocapsid dissolves and the genome is transported to the cell nucleus, then the linear genome circularizes, forming an episome. The cell may then proceed with either lytic infection with release of infectious virus or latent infection of the host cell. B lymphocytes with latent infection undergo growth transformation.

Lytic infection occurs early after primary inoculation. As a result of lytic infection in oral epithelial cells, EBV can be found in the saliva for the first 12-18 months after acquisition of infection. Thereafter, epithelial cells and lymphocytes are latently infected, leading to release of mature virions. Thus, the virus can be isolated from the oral secretions of 20-30% of healthy latently infected individuals at any time.

In 1976, researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden studied the chromosomes in cells from Burkitt lymphoma tumors. They noticed that the same chunk of one particular chromosome had broken off and re-attached to a different chromosome in all the cells. It turned out that the chunk of chromosome that had broken off contained c-myc, an oncogene. C-myc usually tells cells to divide when they are needed, and its activity is tightly controlled, but in the Burkitt lymphoma cells it had landed next to genes that are always turned on in white blood cells. This meant that c-myc became permanently switched on, giving the cells instructions to keep growing. Unbridled proliferative illnesses arise when cellular immunity is grossly defective. [17, 18]

A large analysis concluded that approximately 1 in every 10 stomach cancers contained EBV. [19]

A study by Langer-Gould et al reported that Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 seropositivity was independently associated with increased risk of multiple sclerosis in all racial and ethnic groups. [20]

Etiology

EBV is the etiologic agent in approximately 90% of acute infectious mononucleosis cases. Several other viruses can cause infectious mononucleosis-like illnesses. About 5-10% of illnesses are caused by primary infections with the following:

-

Cytomegalovirus

-

Toxoplasma gondii

-

Adenovirus

-

Viral hepatitis (hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2)

-

HIV

-

Rubella virus

The exact cause remains unknown in majority of EBV-negative infectious mononucleosis-like illnesses.

Epidemiology

The majority of patients with infectious mononucleosis are not hospitalized; hence, the availability of reliable data on the population incidence is limited. The incidence is estimated as between 20 and 70 per 100,000 persons/year. The age-specific distribution of cases reflects the clinical disease ratio of primary EBV infection, which is low in children. The low incidence among older adults reflects the low number of EBV-uninfected individuals. There seems to be no seasonal variation in incidence rates.

A statistically significant association of higher antibody prevalence is noted with each race/ethnicity group, older age, lack of health insurance, and lower household education and income. Factors clearly related to early acquisition of primary EBV infection include geographic region and race/ethnicity, crowding or sharing a bedroom, and socioeconomic status. [21]

There is a complex interplay between age of acquisition, symptomatic versus asymptomatic infection, and the subsequent risk of EBV-associated cancers or autoimmune diseases. Younger age at the time of primary EBV infection was associated with elevated levels of EBV viremia throughout infancy, leading researchers to postulate that these infants were at higher risk for endemic Burkitt lymphoma. [22] Children who acquired primary EBV infection at an earlier age had higher titers of IgG antibody against VCA, and children who were infected with “a large inoculum of EBV” were at high risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. [9] Age of primary EBV infection is an important factor in infectious mononucleosis, and hence it is an important consideration for EBV-related diseases.

United States statistics

Epstein-Barr virus is not a notifiable infection, and the exact frequency of symptomatic primary infection is not known. Incidence in the United States is reported as 500 per 100,000 persons per year. [23] Antibody prevalence across all age groups of US children aged 6-19 years enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) between 2003 and 2010 was substantially higher in non-Hispanic Blacks and Mexican Americans than in non-Hispanic Whites. [24] In younger children, there seems to be greater disparity in antibody prevalence, especially in 6- to 8-year-olds between the races, even though it is similar among teenagers, probably owing to differences in social practices and family environment.

Approximately 50% of the US population is infected by the age of 5 years. During childhood, primary infection is usually asymptomatic or is associated with mild elevation of liver function test findings. EBV infection acquired during adolescence is asymptomatic or is associated with the syndrome of acute infectious mononucleosis. Approximately 90% of the US population is seropositive for EBV by age of 25 years.

The highest incidence is in individuals aged 15-24 years. However, changes in economic status may have changed both the age of initial infection and the incidence of infectious mononucleosis. In lower socioeconomic groups, EBV infection is more common, occurs at an earlier age, and is less likely to be associated with acute infectious mononucleosis.

Roommates of students with primary EBV infection develop seroconversion only at the same rate as the general population of college students [7] .

International statistics

EBV infection occurs with the same frequency and symptomatology in the developed nations of the world as in the United States.

Data from 1990 to 2016 from the Health Survey of England, UK, were analyzed for the seroprevalence of EBV for the process of vaccine trials. The survey showed that approximately 50% of individuals were infected before the age of 5 years. According to the data, seroprevalence in the 5- to 11-year age group was about 55%, which increased slightly in the 12- to 18-year age group, to 65-70%. High levels of infection were seen in the 19- to 24-year age group (about 88%) and in those older than 25 years (about 90%). [25]

EBV is more frequently acquired in childhood in underdeveloped nations, and, therefore, the syndrome of acute infectious mononucleosis is unusual in these nations.

In Africa, the virus is associated with endemic Burkitt lymphoma in the setting of co-infection with Plasmodium falciparum. [6]

High numbers of EBV episomes are found in the cells of undifferentiated or poorly differentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. This is the most common tumor in adult men in southern China and is also common in North American Inuits and North African Whites

Mode of transmission

EBV infection does not occur in epidemics and has relatively low transmissibility.

Kissing is the major route of transmission of primary EBV infection among adolescents and young adults. Penetrative sexual intercourse has been postulated to enhance transmission, but it was found that subjects reporting deep kissing with or without coitus had the same risk of primary EBV infection throughout their undergraduate years. Primary EBV infection can also be transmitted by blood transfusion, [12] solid organ transplantation, [13] and hematopoietic cell transplantation, but these routes account for relatively few cases overall.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Race

Epstein-Barr virus infection has no racial predilection; however, HLA-A2 haplotypes, which are more common in people of Chinese origin, are associated with a predisposition for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The risk associated with HLA-A2 haplotypes is higher than any environmental risk posed by diet. First-generation US immigrants of Chinese origin have a higher risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. [26]

Large epidemiologic studies performed in the 1970s revealed that acute infectious mononucleosis was 30 times more likely to occur in Whites than in African Americans. However, this correlated with lower social economic status and earlier asymptomatic infection in African Americans and, therefore, did not reflect a true racial difference.

Sex

The incidence of infectious mononucleosis is the same in men and women, although the peak incidence occurs 2 years earlier in females. Postinfectious fatigue is more common in females. [27, 28]

Age

Epstein-Barr virus infection usually occurs during infancy or childhood and remains latent through life.

In developed nations, infection may not occur until adolescence or adulthood, and approximately 50% of adolescents who acquire Epstein-Barr virus develop the infectious mononucleosis syndrome.

Acute infectious mononucleosis has been reported in middle-aged and elderly adults; these individuals are usually heterophile antibody negative.

Prognosis

Immunocompetent persons with acute infectious mononucleosis have a good prognosis, with full recovery expected within several months. The common hematologic and hepatic complications resolve in 2-3 months. Neurologic complications usually resolve quickly in children. Adults are more likely to be left with neurologic deficits. All individuals develop latent infection, which usually remains asymptomatic.

Long-term fatigue can occur, is more common in females, and can last 1-2 years or longer. This is separate from the chronic fatigue syndrome mentioned above (although post–Epstein-Barr virus fatigue can occur, chronic fatigue syndrome has not been causally linked to Epstein-Barr virus).

Death is unusual in immunocompetent patients but can occur rarely due to airway obstruction, splenic rupture, neurologic complications, hemorrhage, or sometimes from secondary infection.

Morbidity/mortality

Most primary Epstein-Barr virus infections are asymptomatic. It is perhaps the most common reason for fever of unknown origin in young children and can present with fever in isolation or in the context of lymphadenopathy, fatigue, or nonspecific malaise.

Epstein-Barr virus infection is linked with numerous tumors. Endemic Burkitt lymphoma, the most common tumor of childhood in Africa, is associated with Epstein-Barr virus and malaria. Infection with P falciparum malaria stimulates polyclonal B-cell proliferation with Epstein-Barr virus infection and impairs the T-lymphocyte response to Epstein-Barr virus, apparently contributing to tumor pathogenesis.

In Asia, Epstein-Barr virus infection is related to development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Predisposing factors include a diet rich in nitrosamines, salted fish, Chinese race, and the HLA-A2 haplotype. Most non-Hodgkin lymphomas are associated with Epstein-Barr virus, and evidence of the Epstein-Barr virus genome is demonstrable in many of these tumors.

Epstein-Barr virus is also associated with Hodgkin lymphoma, in which the Epstein-Barr virus genome is present in the Reed-Sternberg cell. The EBNA1 protein interferes with tumor growth factor–beta signaling by downregulating Smad2; this interference with tumor-suppressor functions may contribute to tumor formation. [29] In addition, the same protein may play a role in immune evasion via recruitment of regulatory T-helper cells. [30] The precise mechanism by which Epstein-Barr virus may contribute to tumor pathogenesis are uncertain; some authors suggest that interleukin-10 may be linked to immune evasion, whereas others suggest it is linked to recovery.

Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients who are immunocompromised is associated with several syndromes and proliferative disorders.

Individuals with Duncan syndrome (ie, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome) may develop fatal primary Epstein-Barr virus infection due to a defect in the immune response to Epstein-Barr virus (poor anti-EBNA responses). The defective gene is the signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM)–associated protein (SAP) and is found on the X chromosome. Boys with Duncan syndrome often develop fatal massive hepatitis, hemophagocytosis, or a disseminated lymphoproliferative disorder triggered by primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. The median age of presentation is 2.5 years, with a median survival of 33 days. Survivors of the initial infection develop B-cell lymphoma or hypogammaglobulinemia and usually die by age 10 years. In children with Duncan Syndrome, the paucity of normal class-switched mature B cells means the virus instead establishes itself in nonswitched memory B cells (as opposed to naive or transitional B cells). [31]

Other congenital immunodeficiencies are associated with the development of Epstein-Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative disorders. These include ataxia-telangiectasia, Chédiak-Higashi syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, and common variable immunodeficiency.

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a potentially fatal lymphoproliferative syndrome associated with Epstein-Barr virus and monoclonal or polyclonal expansion of B cells. It occurs in patients after organ transplantation, particularly after heart transplantation, and usually responds to decreased immune suppression.

Epstein-Barr virus–associated lymphomas occur in patients with secondary immunodeficiencies (eg, after cancer chemotherapy). Unfortunately, these tumors do not respond to decreased immunosuppression.

In patients with AIDS, Epstein-Barr virus is associated with hairy leukoplakia, leiomyosarcoma, CNS lymphoma, and lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis in children. However, only approximately one half of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated Burkitt lymphomas contain Epstein-Barr virus genomes, which suggests a more complex interaction between chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and immune system defects. Acyclovir has been shown to have some potential benefit in treating patients with AIDS-associated Epstein-Barr virus disease.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an immune activation syndrome that can be triggered by EBV infection, especially in immunocompromised patients. HLH can also be triggered by other infections, [32] and inherited HLH exists as well, which typically presents at a very young age.

HLH is characterized by multiorgan dysfunction and cytopenias, and laboratory findings that overlap with severe EBV infection and leukemia. Typical presentations are fever, hepatosplenomegaly, rash, and pancytopenia. Various laboratory findings are suggestive of HLH, including high ferritin, high triglycerides, and low fibrinogen, as well as cytopenia in at least 2 cell lines. The most specific serologic marker is high levels of soluble interleukin 2 receptor. Low natural killer cell number and activity is also a sensitive marker for HLH.

A study by Langer-Gould et al reported that Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 seropositivity was independently associated with increased risk of multiple sclerosis (MS) in all racial and ethnic groups. [20] Other studies have also suggested an association between EBV infection and subsequent development of MS. [1] A trial by Bjornevik et al found that the risk of MS increased 32-fold after EBV infection. [33] Results of a study by Cortese et al similiarly showed that higher total anti-EBV nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA-1) antibody levels have consistently been linked to a greater risk of MS. [34]

Complications

Complications encountered after infectious mononucleosis include the following:

-

Acute interstitial nephritis

-

Hemolytic anemia

-

Myocarditis and cardiac conduction abnormalities

-

Neurologic abnormalities, multiple sclerosis

-

Cranial nerve palsies

-

Encephalitis

-

Aseptic meningitis

-

Mononeuropathies

-

Retrobulbar neuritis

-

Thrombocytopenia

-

Upper airway obstruction due swollen tonsils

Hepatitis develops in more than 90% of patients with infectious mononucleosis. Liver function test results are mildly elevated but are usually no more than 2-3 times the reference range. Bilirubin levels are elevated in approximately 45% of patients, but jaundice occurs in only 5%. Liver abnormalities are most pronounced in the second and third weeks of illness.

Approximately 50% of patients with infectious mononucleosis develop mild thrombocytopenia. The platelet count is usually 100,000-140,000/mL. The platelet count usually reaches its nadir approximately 1 week after symptom onset and then gradually improves over the next 3-4 weeks. Thrombocytopenia may be caused by the production of antiplatelet antibodies and peripheral destruction, especially in the enlarged spleen.

Hemolytic anemia occurs in 0.5-3% of patients with infectious mononucleosis. Hemolytic anemia has been associated with cold-reactive antibodies, with anti-I antibodies, and with autoantibodies to triphosphate isomerase. Hemolysis is usually mild and is most significant during the second and third weeks of symptoms.

Upper airway obstruction due to hypertrophy of tonsils and other lymph nodes in the Waldeyer ring occurs in 0.1-1% of patients. Treatment with corticosteroids may be beneficial. Patients with severe tonsillar and lymph node enlargement with impending airway obstruction may require intubation or tracheostomy. Patients who require hospitalization may have concurrent streptococcal pharyngitis. Two thirds of patients admitted with infectious mononucleosis with upper airway obstruction and dehydration have alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus infection, usually due to group C streptococci.

Splenic rupture occurs in 0.1-0.2% of patients with infectious mononucleosis. A literature review by Bartlett et al indicated that the risk of splenic rupture is greatest in males under 30 years with infectious mononucleosis symptom onset within the previous 4 weeks. [35] Rupture may be spontaneous, although the patient often has a history of some antecedent trauma. Rupture is most likely during the second and third weeks of clinical symptoms. Patients can present with mild-to-severe abdominal pain below the left costal margin, sometimes with radiation to the left shoulder and supraclavicular area. Massive bleeding may be accompanied by peritoneal irritation and shifting dullness. Shock may be the only presenting symptom. Because bradycardia is common in infectious mononucleosis, tachycardia with pulse of faster than 100 beats per minute is an important sign. Neutrophilia (instead of lymphocytosis) can occur. Surgical intervention is usually required.

Hematologic complications are as follows:

-

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura occurs and may evolve to aplastic anemia. Aplastic anemia and neutropenia are sometimes associated with antineutrophil antibodies.

-

Epstein-Barr virus infection may accelerate hemolytic anemia in individuals with congenital spherocytosis or hereditary elliptocytosis.

-

Disseminated intravascular coagulation associated with hepatic necrosis has occurred.

Neurologic complications are as follows:

-

Neurologic complications occur in less than 1% of patients with Epstein-Barr virus infections and usually develop during the first 2 weeks. In some patients, especially children, the neurologic symptoms are the only clinical manifestation of infectious mononucleosis [39] . Patients are often negative for the heterophile antibody. However, these complications are often severe. Complete recovery is the rule, but fatalities do occur.

-

Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection has been associated with aseptic meningitis, acute viral encephalitis,and meningoencephalopathy. Hypoglossal nerve palsy, Bell palsy, brachial plexus neuropathy, and multiple cranial nerve palsies have been described. Guillain-Barré syndrome, autonomic neuropathy, GI dysfunction secondary to selective cholinergic dysautonomia, acute cerebellar ataxia, and transverse myelitis also have been reported. Metamorphopsia (ie, Alice in Wonderland syndrome) has been described.rarely.

Cardiac and pulmonary complications are as follows:

-

Pulmonary complications are extremely rare, although upper airway obstruction due to lymphoid hypertrophy is relatively common. Chronic interstitial pneumonitis and pleural effusion have been associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection.

-

Cardiac abnormalities that can occur with Epstein-Barr virus infection include myocarditis and pericarditis.

Autoimmune complications are as follows:

-

Haemolytic anaemia is reported in patients who had infectious mononucleosis

-

Infectious mononucleosis stimulates production of many antibodies not directed against Epstein-Barr virus. These include autoantibodies, anti-I antibodies, cold hemolysins, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factors, cryoglobulins, and circulating immune complexes. These antibodies may precipitate autoimmune syndromes.

Miscellaneous complications are as follows:

-

Renal disorders associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection include interstitial nephritis, renal failure, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.

-

After cardiac bypass or transfusion, an infectious mononucleosis–like syndrome has been described. Epstein-Barr virus may cause this, but it is more commonly associated with primary CMV infection.

-

Chronic fatigue syndrome- 20 % feel fatigue at 2 months and 13% at 6 months after primary infectious mononucleosis [39] . Myalgias, depression and hypersomnia is also reported to be associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection.

Antibiotic-induced rash (ampicillin rash)

A rash develops in nearly all adults (less commonly in children) 5-10 days after starting treatment with ampicillin, amoxicillin, or other beta-lactam antibiotics. It has also been associated with azithromycin. Even though it is associated with penicillins, this rash does not represent a true penicillin allergy. Rash is typically maculopapular and pruritic. It resolves in a few days when the antibiotic is discontinued. [40]

Splenic rupture

Owing to massive infiltration with lymphocytes, splenic rupture occurs in 0.1-0.5% of cases, with a mortality rate of up to 30%. [41] The average time between onset of symptoms and rupture is 2 weeks (range, up to 8 weeks). The complication affects mostly males, with an average age of 22 years.

The spleen may dramatically enlarge and become vulnerable to spontaneous rupture, or rupture from minor trauma. However, a preceding history of trauma has been reported in only 14% of patients. [42]

The most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain, which is reported in 88% of patients. [42]

Although splenectomy is often performed in the majority of patients, careful serial observation or spleen-sparing interventions may be considered. [43] . Observation and supportive care may suffice occasionally in hemodynamically stable patients.

Occasionally, splenic infarction has also been reported. [44]

Neurologic complications

Encephalitis occurs usually during the first 2 weeks in 1% of adolescent and adult IM cases. In an etiological study of encephalitis in children, up to 6% of cases had strong evidence of current EBV infection. [45]

Other possible complications include aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, cranial nerve palsies, sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis, acute cerebellar ataxia, and rarely psychosis.

Autoimmune disease

An association between EBV infection and autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus, has been reported.

Malignancy

Because EBV is an oncovirus, long-term complications due to various malignancies involving lymphoreticular tissues can lead to varying degrees of morbidity and mortality.

EBV infection has been associated with a number of different malignancies of both lymphoid and epithelial origin, and it accounts for 1.8% of all cancer-related deaths worldwide. [45] EBV infection is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, and Hodgkin's disease in patients in developing countries.

Patients with primary or aquired immunodeficiency, or those immunosuppressed by organ transplantation, are at increased risk for potentially fatal EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders, such as post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, and B-cell lymphomas. [46]

Chronic fatigue syndrome

There is evidence of a distinct fatigue syndrome 6 months after diagnosis. A prospective study of patients with EBV-IM found that patients required nearly 2 months to achieve pre-illness functional status. [47] Female sex and pre-morbid mood disorder are risk markers for post-IM fatigue.

Chronic fatigue should be present for at least 6 months for a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS); post-IM fatigue may be of shorter duration.

The possibility that EBV infection leads to CFS has been reported in studies. No strong data exist to date to routinely implicate EBV as an etiologic agent. [48, 49] Post-infective CFS can result from several viral and nonviral infections, which represent a common stereotyped outcome.

Younger patients with CFS after infectious mononucleosis who had long-term incapacity for work experienced marked improvement over time, and the long-term outcome is good.

Renal complications

Interstitial nephritis, myositis-associated acute kidney injury, hemolytic uremic syndrome, and jaundice-associated nephropathy have been reported in patients with acute symptomatic infectious mononucleosis. Rarely, the outcome is potentially fatal, and renal-replacement therapy may be required. [50]

Acute acalculous cholecystitis

This can be an atypical clinical presentation of EBV infection. [51]

Chronic active infectious mononucleosis

Very rarely, few patients develop chronic active disease with intermittent or continuous symptoms of fever, hepatosplenomegaly, malaise and fatigue, abnormal liver function tests, and thrombocytopenia for over 6 months, which carries a poor prognosis with high mortality. [52]

Death is usually due to lymphoma, hemophagocytic syndrome, or fulminant hepatitis.

Patient Education

Following contact with the patient, carefully wash hands with soap and running water. Avoid any contact with the saliva of the affected patient. Advise patients that after sneezing and coughing they should clean up before touching other people. Tell patients to avoid sharing water bottles, eating and drinking containers, and utensils. In day care units, avoidance of sharing of cutlery and plates, which may be soiled with saliva, should be emphasized. Because transmissibility is low, there is no point in isolating affected patients.

Owing to splenomegaly, which can occur during the first 3 weeks of illness, the routine recommendation is to restrain from strenuous physical activity for up to 8 weeks or until all symptoms subside. [53] A follow-up abdominal ultrasound scan to evaluate spleen size is helpful in advising patients who are athletes or those who participate in contact or collision sports. If no splenomegaly is detected, return to sports after 1 week can be allowed once symptoms subside.

-

Infectious mononucleosis. Antibody response to Epstein-Barr virus. Adapted with permission from Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Epstein-Barr virus serology. Infect Dis Pract. 1995;19:26-27.