Practice Essentials

Cysticercosis is a tissue infection that involves larval cysts of the cestode Taenia solium (the human pork tapeworm). It results from the ingestion of food (especially vegetables) and water contaminated with human feces that contain T solium eggs.

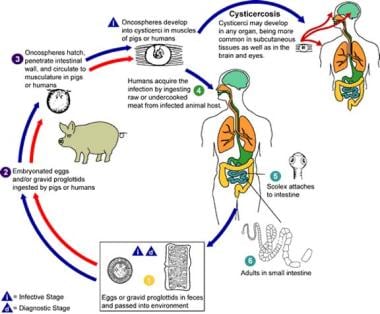

Although infections with Taenia tapeworm cysts may involve many parts of the body, the most common site of severe symptomatic infection is the CNS. See the image below.

Neurocysticercosis, the most common parasitic disease of the CNS, is the most frequent cause of adult-onset epilepsy in many of the countries where the infection is endemic.

Signs and symptoms of cysticercosis

The clinical presentation depends on the number, location, and stage of the lesions, as well as the host immune response. In general, the following may be present:

-

Neurologic deficits

-

Seizures

-

Subcutaneous or ocular cysts

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis of cysticercosis

Laboratory studies

The enzyme immunotransfer blot assay for the detection of serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) antibodies to T solium is the antibody test of choice for cysticercosis.

The complement fixation test for the detection of antibodies in CSF is highly specific and sensitive.

Imaging studies

The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis is based primarily on computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results. Regardless of the neuroimaging modality, granulomas are the most common finding in patients with neurocysticercosis.

See Workup for more detail.

Management of cysticercosis

Medical treatment depends on the location of the cysts and the patient’s symptoms. Patients with live parenchymal cysts can be treated with either albendazole or praziquantel; however, corticosteroids and antiseizure medications are often required in addition. Those with nonviable (calcified) brain cysts should be treated only for their symptoms; anticonvulsants are used to treat seizures.

For cases that do not respond to medical therapy, shunt placement, removal of large solitary cysts for decompression, and the removal of mobile cysts that cause ventricular obstruction should be considered.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Pathophysiology

Cysticercosis, the intermediate form of T solium infection, is predominantly acquired by ingesting food or water contaminated with T solium eggs. Additionally, autoinfection may occur by means of fecal-oral contact and, theoretically, by reverse peristalsis in the small intestines of individuals infected with adult T solium worms.

In the stomach, oncospheres are liberated following digestion of the eggs' coats. Oncospheres invade and cross the intestinal wall, enter the bloodstream, and then migrate to and lodge in tissues throughout the body, where they produce small (0.2-0.5 cm) fluid-filled bladders containing a single juvenile-stage parasite (protoscolex).

Although the cysticerci may infect any organ of the body (most often the eye, skeletal muscle, and CNS), serious disease almost exclusively involves the CNS and heart.

Oncospheres that invade the brain may lodge in the brain parenchyma, subarachnoid space, ventricular space, or spinal cord. Cysticerci develop after 2 months and may or may not stimulate an appreciable inflammatory response.

In the brain parenchyma, cysticerci form a thin capsule of fibrous tissue that thickens with time. After several years, the parasite dies or is killed and is replaced by an astroglial and fibrous tissue granuloma that becomes calcified. The number of cysticerci present ranges from one to several hundred.

Cysts that grow in the sylvian fissure and in the subarachnoid space at the base of the skull may enlarge to 10-15 cm in diameter. Meningeal and spinal cord cysticercosis occurs if the oncospheres enter via the choroid plexus and hatch in the arachnoid membranes along the neural axis.

Cysts that develop in the subarachnoid space may cause an inflammatory response. Subsequent fibrosis of the arachnoid membranes may interfere with normal cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) resorption, resulting in hydrocephalus. Fourth ventricle cysts can create a subacute hydrocephalus via a valve-and-ball mechanism. However, head movement can suddenly increase the intracranial pressure (ICP).

With the exception of massive or obstructive disease, the cystic stages of most tapeworms do not provoke a strong immunologic response while they remain alive and intact. However, once the cysts die, the immune system recognizes them as foreign, and a vigorous immunologic response ensues. Seizures, hydrocephalus, blindness, strokes, meningitis, encephalitis, irreversible brain damage, myositis, and myocarditis may occur. Death may subsequently occur.

Etiology

Cysticercosis is caused by the ingestion of T solium eggs. The human is the only definitive host of the adult pork tapeworm, which lives in the human intestinal tract and lays eggs that are shed in human feces. In the normal life cycle of the parasite, eggs shed in human feces are ingested by pigs, which then develop cysticerci in muscle tissue. Human infection with the adult tapeworm develops in people who ingest raw or poorly cooked pork that contains cysticerci. Note that human ingestion of pork does not result in the development of cysticercosis.

Contamination of water, fruits, and vegetables by human feces that contain eggs is usually the result of poor sanitation.

Untreated, adult T solium worms may cause autoinfection by means of fecal-oral ingestion and reverse peristalsis, but this is believed to be very uncommon.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Cysticercosis is not endemic to the United States, although domestic transmission has been documented from recent immigrants to the United States from highly endemic areas. [1] Historically, rates significantly decreased in the 1970s.

Since the 1970s, the number of cases of neurocysticercosis in the United States has increased, mainly because of the large number of immigrants from areas with endemic disease, such as Mexico, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, Spain, and Portugal. Americans without a travel history to such areas have developed neurocysticercosis, mainly because of exposure to a cohabitant with a T solium infection.

A review of hospitalization discharge data from the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample for 2003-2012 found that neurocysticercosis hospitalizations and hospital-associated charges for neurocysticercosis in the United States are greater than for all other neglected and tropical diseases combined, including malaria. Most hospitalizations were for management of seizures and obstructive hydrocephalus, with Hispanic young adult males at greatest risk. [2] This study did not analyze outpatient visits or charges.

About three quarters of patients hospitalized in the United States with neurocysticercosis were Hispanic in 2003-2012.

The number of hospitalizations and costs to the US healthcare system is expected to increase due to immigration of persons from Latin America, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

International statistics

Disease is prevalent in areas with low socioeconomic status and poor hygiene and sanitation. Accurate estimation of the prevalence of cysticercosis is difficult because of the high prevalence of asymptomatic individuals. Overall, more than 2 million people are estimated to have adult tapeworm infection, and many more are infected with cysticercoids. Disease is prevalent in areas with poor hygiene and sanitation where pigs live in close proximity to people.

Cysticercosis is endemic throughout Latin American, although it is rare in Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. It is endemic in South Asia (especially India) as well as in sub-Saharan Africa.

In Madagascar, a population-based study by Carod et al investigated the prevalence of cysticercosis among schoolchildren (n = 1751) using the B158/B60 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. They found that the overall prevalence based on antigen detection was 27.7% (95% CI, 10-37%). [3]

Cysticercosis is absent in Arabic regions of Asia and Africa but is found in areas where pigs live in close proximity to humans. In Europe, cysticercosis is still endemic in Spain, Portugal, and some Eastern European countries but is rare in most other countries.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No racial predilection for cysticercosis is known.

The prevalence does not differ according to sex.

No known age-based differences in the frequency of cysticercosis have been reported.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the number and location of lesions, as well as the host response. Treatment with antihelminthics may result in radiologic improvement of CNS lesions, but this may or may not result in clinical improvement.

Morbidity/mortality

Worldwide, an estimated 50,000 people die of cysticercosis each year because of CNS or cardiac complications.

Complications

Complications of cysticercosis are numerous. They are most severe when they involve the CNS, visual, or cardiac system.

Permanent brain damage, seizures, strokes, hydrocephalus, and vague neurologic symptoms may result. Blindness often results from ocular cysticercosis, despite antiparasitic and surgical treatment. Muscle involvement may result in myositis and myocarditis.

Patient Education

Improved sanitation and hygiene are essential to the prevention of cysticercosis.

Use of toilets and proper disposal of human feces that may contain tapeworm eggs may eliminate transmission of infection. Avoid ingestion of unclean water. Proper cooking of pork may result in fewer T solium infections.

Prevention and Control

Cysticercosis was declared a potentially eradicable disease by the International Task Force for Disease Eradication in 1992. Attempts at eradication and disease prevention have been limited to demonstration projects in targeted villages in endemic areas, and have had only limited and transitory effects. Studies of disease eradication have shown that T solium is extremely resistant to control in low-income countries.

A study in an endemic region in northern Peru found that it was feasible to interrupt transmission of T solium with prevention of human and porcine cysticercosis, but persistence of eradication requires intense and continuous measures that are costly and are currently not feasible in low-income countries. [4]

-

Cysticercosis life cycle. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

MRI of 6-year-old boy from Peru with single right frontal cyst (coronal image). Image courtesy of Eric H. Kossoff, MD.

-

Axial image MRI of same patient as in Media file 2. Image courtesy of Eric H. Kossoff, MD.

-

CT scan of intraparenchymal cysticercosis with lesions in different stages. Lesions that are breaking down demonstrate peripheral enhancement after intravenous contrast injection, whereas lesions without peripheral enhancement are intact. Typical residual calcification from an old focus of infection is observed in the left occipital lobe. Image courtesy of Fred Greensite, MD.

-

Racemose (extraparenchymal) cysticercosis (T1-weighted MRI). Note the cyst in the fourth ventricle, causing obstructive hydrocephalus. Image courtesy of Fred Greensite, MD.

-

Racemose cysticercosis (T1-weighted MRI). Note cluster of cysts anterior to the pons and inferior to the hypothalamus in a different patient. Image courtesy of Fred Greensite, MD.

-

Racemose cysticercosis (same patient as in Media file 6). Note the enhancing margin of the cysts in the suprasellar cistern and in the left sylvian fissure after gadolinium injection (T1-weighted MRI). Image courtesy of Fred Greensite, MD.

-

Racemose cysticercosis (same patient as in Media files 6-7). Coronal image (postgadolinium T1-weighted MRI) posterior to the slice in Media file 7. Cysts in this slice (below the hypothalamus) do not have enhancing margins. Also, unlike intraparenchymal lesions, scolexes are typically not identified in the cysts of racemose cysticercosis. Image courtesy of Fred Greensite, MD.