Background

Craniopharyngiomas (see image below) are histologically benign neuroepithelial tumors of the CNS that are predominantly observed in children aged 5-10 years.

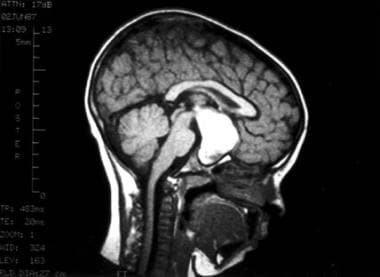

This MRI sequence was obtained following the intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast. Observe the relatively homogeneous and cystic mass arising from the sella turcica and extending superiorly and posteriorly with compression of normal regional structures. Note that the lesion is sharply demarcated and smoothly contoured. This fluid-filled mass is consistent with a typical craniopharyngioma.

This MRI sequence was obtained following the intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast. Observe the relatively homogeneous and cystic mass arising from the sella turcica and extending superiorly and posteriorly with compression of normal regional structures. Note that the lesion is sharply demarcated and smoothly contoured. This fluid-filled mass is consistent with a typical craniopharyngioma.

These tumors arise from squamous cell embryologic rests found along the path of the primitive adenohypophysis and craniopharyngeal duct. Although histologically benign, these tumors frequently recur after treatment. In addition, because they originate near critical intracranial structures (eg, visual pathways, pituitary gland, hypothalamus), both the tumor and complications of curative therapy can cause significant morbidity.

No known environmental or infectious causes predispose to the development of craniopharyngiomas.

Pathophysiology

Pediatric craniopharyngiomas are believed to arise from cellular remnants of the Rathke pouch, which is an embryologic structure that forms both the infundibulum and anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Its path of development extends from the pharynx to the floor of the sella turcica; not surprisingly, these tumors have been identified extensively in suprasellar, parasellar, and ectopic locations. [1] Typically, the tumors arise within the sella or adjacent suprasellar space.

The WHO classification of central nervous system tumors divides craniopharyngiomas into three histologic subtypes: adamantinomatous, found in children, papillary, found in adults, and mixed. [2]

Studies have demonstrated that the histologic subtypes of craniopharyngioma have distinct molecular signatures that play a role in tumorigenesis. [3] Mutations in the beta-catenin pathway, ie, CTNNB1, have been found in adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma in the pediatric population, and BRAF mutations have been identified in papillary craniopharyngioma in adults. [4, 5] Beta-catenin is a downstream component of the Wnt signal transduction pathway. Intranuclear accumulation of beta-catenin results in enhanced expression of target genes that play a critical role in cellular proliferation and differentiation. The accumulation of nuclear beta-catenin can also be used diagnostically to help distinguish Rathke cleft cysts from adamantinomatous or papillary craniopharyngiomas on immunohistochemistry. [6, 7] Investigations are ongoing to harness the therapeutic implications of these mutations.

Paracrine signaling mechanisms resulting in a pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment have also been hypothesized to drive adamantinomatous tumor behavior. [8] Additional molecular factors have been implicated in aggressive or recurrent craniopharyngiomas, including low expression levels of macrophage-inhibiting factor (MIF), galectins, retinoic-acid receptors isotypes, and cathepsins, and high levels of vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels, however additional studies are needed to elucidate the clinical implications of these findings. [9, 10]

Epidemiology

United States statistics

Craniopharyngiomas are relatively rare, representing 6-10% of intracranial malignancies in children and adolescents (approximately 2-3 cases per 1,000,000 children). A bimodal distribution peak has been reported, with one peak at age 5-14 years and the other at age 65-74 years. More than 300 cases are reported in the United States annually, and roughly one third of these involve children aged 0-14 years. [4, 11, 12] Craniopharyngiomas are the most common childhood tumor that occur in the sella-chiasmatic region. [13]

International statistics

The Childhood Cancer Registry of Piedmont, Italy estimates an incidence of 1.4 cases per million children per year in keeping with reports from other Western countries. Higher incidence rates have been observed in Asia and Africa with about 4 cases per million children reported in Japan in one series. [14]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No clear racial predilection has been reported.

The most recent large series demonstrate equal sex distribution, although a slight male preponderance has been historically reported.

Peak incidence of childhood craniopharyngiomas occurs in individuals aged 5-14 years. Neonatal craniopharyngiomas are rare. Of the more than 300 cases per year in the United States, approximately one third involve children aged 0-14 years. The incidence of adult craniopharyngiomas has a second peak in individuals aged 50-74 years.

Prognosis

Previous studies have shown relatively good outcomes, with 10-year overall survival rates of 86-100% among patients who underwent gross total resection. Subtotal resection or recurrence treated with surgery and radiation therapy carry 10-year overall survival rates of 57-86%. The perioperative mortality rate after primary surgical intervention has been estimated to be 1.7-5.4%. However, the mortality rate after re-resection for recurrent disease can be as high as 25%. [13] It should be noted that given the high morbidity with attempted gross total resection of these challenging tumors, subtotal resection with radiation therapy is considered an acceptable approach.

Yosef and colleagues looked at the impact of initial tumor size on outcomes. They looked at tumors less than 4.5 cm maximum diameter versus tumors greater than 4.5 cm in diameter. They termed the large craniopharyngiomas, “giant” craniopharyngiomas and found them to be associated with greater residual post-operative tumor and significantly decreased 2 and 5 year PFS versus smaller tumors (33.3 vs. 73.3% and 33.3 vs. 53.3% respectively). [15]

Morbidity/mortality

Almost all patients with craniopharyngioma ultimately suffer from chronic morbidities. These are most commonly endocrinologic in nature but also include significant neurologic morbidities such as vision loss, ataxia, behavioral problems, cognitive disabilities, and sleep disorders.

-

This MRI sequence was obtained following the intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast. Observe the relatively homogeneous and cystic mass arising from the sella turcica and extending superiorly and posteriorly with compression of normal regional structures. Note that the lesion is sharply demarcated and smoothly contoured. This fluid-filled mass is consistent with a typical craniopharyngioma.

-

This axial CT scan image demonstrates a cystic lesion in the typical location of a craniopharyngioma. Although most of the lesion is fluid filled, a rim of enhancing soft tissue is observed following the administration of intravenous contrast.

-

Non-contrast head CT scan with peripheral calcifications around a bi-lobed craniopharyngioma.