Practice Essentials

Hemorrhagic cystitis is defined by lower urinary tract symptoms that include hematuria and irritative voiding symptoms. It results from damage to the bladder's transitional epithelium and blood vessels by toxins, pathogens, radiation, drugs, or disease.

Infectious causes of hemorrhagic cystitis include bacteria and viruses. Noninfectious hemorrhagic cystitis most commonly occurs in patients who have undergone pelvic radiation (see the image below), chemotherapy, or both. [1] Affected patients may develop asymptomatic microscopic hematuria or gross hematuria with clots, leading to urinary retention. Treatment depends on the etiology, severity of the bleeding, and symptoms. [2]

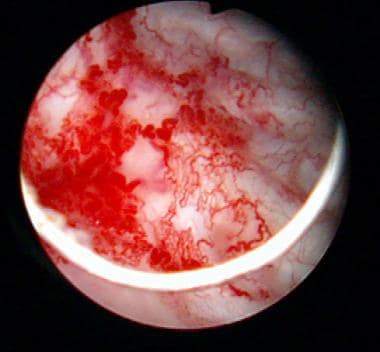

Changes associated with irradiation cystitis, which developed after 7200cGy external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer.

Changes associated with irradiation cystitis, which developed after 7200cGy external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer.

Patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation frequently have hemorrhagic cystitis because most are exposed to cyclophosphamide, total-body irradiation, or both. Patients with malignancies and those undergoing chemotherapy are often immunocompromised and are at high risk of acquiring bacterial and viral infections that can cause hemorrhagic cystitis.

Rarely, arteriovenous malformations, stones, metastatic tumors, and, more commonly, urothelial malignancies produce gross hematuria. These are differentiated from hemorrhagic cystitis with imaging and endoscopic evaluation. [3]

For patients receiving drugs or undergoing procedures that are known to cause hemorrhagic cystitis, prevention is essential. Two standard methods of preventing cyclophosphamide-related bladder toxicity are hyperhydration and mesna administration. [4] Controversial methods include prophylactic bladder irrigation and hourly voiding.

Physicians treating oncology patients must be aware of the possible preventive measures against hemorrhagic cystitis.

Patient education

Patients at high risk must be educated about the possibility of the development of hemorrhagic cystitis and the need for early intervention. For patient education information, see Blood in the Urine.

Anatomy

The bladder anatomy relevant to noninfectious hemorrhagic cystitis includes an appreciation of the layers from the lumen outward. The glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer coats the inner surface over the transitional epithelium. Deep to this transitional epithelium, which is covered superficially by “umbrella” cells, the bladder submucosa with its microvasculature overlies the detrusor muscle, which is smooth muscle oriented in multiple directions to allow for uniform stretching and the storage of urine. A layer of fatty connective tissue surrounds most of the anterior and lateral bladder in the space of Retzius, while, posteriorly, the peritoneal serosal surface separates it from the cul-de-sac and abdominal cavity contents.

In cases of chronic cystitis, neovascularity in the submucosal area is common and is presumably the site of acute hemorrhage. Ischemic changes related to endarteritis can lead to mucosal ulcerations and acute hemorrhage.

Pathophysiology

Hemorrhagic cystitis results from damage to the bladder's transitional epithelium and blood vessels by toxins, viruses, radiation, drugs (in particular, chemotherapeutic drugs), bacterial infections, or other disease processes. Histologically, the bladder wall demonstrates nonspecific findings of intense inflammatory infiltrates, chronic inflammation, and fibrosis. [5]

Cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis

Cyclophosphamide is the most common cause of hemorrhagic cystitis in the oncologic population. The urotoxicity observed with cyclophosphamide is due to its liver metabolite acrolein, which is excreted in the urine. Although the entire urothelium is at risk of urotoxicity, the bladder, which serves as a reservoir, is most frequently affected, because the contact time between acrolein and the urothelium is greatest at this site.

Adverse urologic effects of cyclophosphamide include the following:

-

Frequency

-

Dysuria

-

Urgency

-

Suprapubic discomfort

-

Microscopic and gross hematuria

Rare adverse effects include the following:

-

Bladder wall necrosis

-

Bladder fibrosis with resultant loss of compliance

-

Contracture, or shrinkage of bladder reservoir volume

-

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR)

-

Tumor formation

Radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis

Radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis is most common in patients receiving pelvic irradiation. Hematuria may develop acutely during radiation treatment or months to years later.

The symptoms of radiation cystitis are caused by a microscopic progressive obliterative endarteritis that leads to mucosal ischemia. The ischemic bladder mucosa then ulcerates and bleeding ensues. Neovascular ingrowth to the damaged area, as shown in the images below, then occurs, causing the characteristic vascular blush on cystoscopic evaluation. The new vessels are more fragile and may leak (petechiae) with bladder distention, minor trauma, infection, or any mucosal irritation.

Changes associated with irradiation cystitis, which developed after 7200cGy external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer.

Changes associated with irradiation cystitis, which developed after 7200cGy external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer.

Neovascularity associated with irradiation cystitis. When distended, these weak-walled vessels often rupture, resulting in submucosal hemorrhage and gross hematuria.

Neovascularity associated with irradiation cystitis. When distended, these weak-walled vessels often rupture, resulting in submucosal hemorrhage and gross hematuria.

Submucosal hemorrhage and overt hematuria may begin precipitously. Acute episodes of radiation cystitis wane within 12-18 months in most patients following radiation therapy. [6, 7, 8]

Etiology

Hemorrhagic cystitis has both infectious and noninfectious causes. Although the noninfectious causes of hemorrhagic cystitis vary, this condition most commonly develops as a complication of pelvic radiation or from toxicity related to the use of certain chemotherapeutic drugs (eg, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide). Less commonly, exposure to certain industrial chemicals, such as aniline or toluidine derivatives, causes hemorrhagic cystitis.

Rarely, drugs such as penicillins or danazol can also precipitate hemorrhagic cystitis. Other, extremely rare reports include associations with food poisoning (from Salmonella typhi) [9] and prolonged high-altitude air travel (Boon disease). [10]

Regardless of the perceived circumstance, an infectious etiology should be sought as part of the initial assessment, even in the setting of radiation or chemical exposure, as infection may serve as an exacerbating factor. Bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and especially viral bladder infections in immunocompromised patients are often complicated by hemorrhage. Reported causative infectious agents for hemorrhagic cystitis include the following:

-

Escherichia coli

-

Adenoviruses 7, 11, 21, and 35

-

Papovavirus

-

Influenza A

Radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis

Nearly 25% of patients who undergo pelvic radiation develop bladder-related complications. Mucosal ischemia secondary to radiation injury results from endarteritis inducing hypoxic surface damage, ulceration, and bleeding. The incidence in the pediatric population is less than that in adults. Slightly less than 50% of these patients develop diffuse hematuria.

Patients with radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis have usually undergone radiation therapy for cancer of the prostate, colon, cervix, or bladder. Urgency, frequency, dysuria, and stranguria may develop acutely during radiation or may begin months to years after completion of radiotherapy.

The higher the dose and the wider the field encompassed by the radiation exposure, the more likely radiation cystitis becomes. Because of the cumulative dose effect, patients who have undergone pelvic radiation are at an increased risk for radiation cystitis if additional radiotherapy is performed. Infection, bladder outlet obstruction, and instrumentation are all factors that can exacerbate radiation cystitis. [11]

Drug-induced hemorrhagic cystitis

Chemotherapeutic drugs

The most common pharmacologic causes of hemorrhagic cystitis are the oxazaphosphorine-alkylating agents cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. [12, 13, 14] Unfortunately, the toxicity of these drugs is not insignificant, and many of the adverse effects are urologic.

Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) is used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (as part of the CHOP regimen) and breast cancer, as well as in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, and as an orphan drug in systemic sclerosis. Specifically pediatric uses include juvenile idiopathic arthritis/vasculitis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The incidence of adverse urologic effects with cyclophosphamide varies from 2-40%, and the toxicity is dose-related. In pediatric patients, adverse effects are typically seen after oral doses greater than 90 g and intravenous doses greater than 18 g, and they occur more commonly in patients receiving intravenous treatment.

Cyclophosphamide can cause microscopic and gross hematuria. The onset of hematuria usually occurs within 48 hours of treatment. [15] Cyclophosphamide is also associated with bladder cancer, which is typically aggressive. [16]

Cyclophosphamide itself is not toxic; the drug's toxicity is due to its hepatic conversion to the metabolite acrolein, which is excreted in the urine and causes bladder edema and bladder hemorrhage. Over time, chronic bladder damage manifests as fibrosis with decreased capacity, trabeculations, and telangiectasias. The adverse effects of cyclophosphamide are more likely due to increased bladder exposure to acrolein. [17]

Hemorrhagic cystitis secondary to cyclophosphamide therapy is most prevalent in patients who are dehydrated. Thus, patients receiving cyclophosphamide should always receive good hydration, and a Foley catheter is often placed to ensure immediate drainage of the bladder. [18, 19] Continuous bladder irrigation is sometimes recommended to hasten acrolein clearance from the bladder. [20]

Ifosfamide (Ifex) is approved for use in germ cell testicular cancer, and as an orphan drug for treatment of sarcomas of soft tissue and bone. Hemorrhagic cystitis due to ifosfamide therapy is generally worse than that caused by cyclophosphamide. [21] Ifosfamide causes the release of tumor necrosis factor – alpha and interleukin-1 beta, mediating the release of nitric oxide and leading to hemorrhagic cystitis. [22, 23]

Penicillins

In rare cases, penicillins have been reported to cause hemorrhagic cystitis. Case reports have implicated the following agents:

-

Methicillin

-

Carbenicillin

-

Ticarcillin

-

Piperacillin

-

Penicillin VK

Most cases of hemorrhagic cystitis in patients taking extended-spectrum penicillins have been reported in individuals with cystic fibrosis who had previously received penicillin antibiotics.

Symptoms can take up to 2 weeks to develop after the drug is started; when symptoms occur, the best treatment is to discontinue the offending drug immediately. Hemorrhagic cystitis in patients taking penicillins is thought to be caused by an immune-mediated hypersensitivity. Examination of the urine frequently reveals eosinophils. [24, 25, 26]

Danazol

Treatment with danazol, a semisynthetic anabolic steroid, has caused hemorrhagic cystitis in patients with hereditary angioedema. Interestingly, the advent of hemorrhagic cystitis in these patients has followed years of symptom-free treatment with the drug. Hematuria developed after 30-77 months of treatment in one study. In almost all cases, the hematuria resolved after cessation of danazol. The dose of danazol did not correlate with the severity of hemorrhagic cystitis. The etiology of hemorrhagic cystitis from danazol is unclear. [27]

Other medications

Medications that have been implicated in the development of hemorrhagic cystitis in limited reports include the following:

-

Temozolomide [28]

-

Bleomycin [29]

-

Tiaprofenic acid [30]

-

Allopurinol [31]

-

Methaqualone [32]

-

Methenamine mandelate [33]

-

Ether

-

Intravesical acetic acid. [40]

Risperidone has been associated with hemorrhagic cystitis but is also used as treatment for hemorrhagic cystitis due to JC virus. [41]

A chemical hemorrhagic cystitis can develop when vaginal products are inadvertently placed in the urethra. Gentian violet douching to treat candidiasis has resulted in hemorrhagic cystitis when the drug has been misplaced in the urethra, but this hemorrhagic cystitis has resolved spontaneously with cessation of treatment. [34, 36, 37]

Accidental urethral placement of contraceptive suppositories has also caused hemorrhagic cystitis in several patients. In this case, the bladder irritation was thought to be caused by contact of the acidic compound nonoxynol-9 (pH, 3.35) with the bladder. In the acute setting, the bladder can be copiously irrigated with alkalinized normal saline to minimize bladder irritation. [38, 39]

Chemically induced hemorrhagic cystitis

Cases of hemorrhagic cystitis with no infectious etiology have been reported in patients who have been in contact with certain urotoxic chemicals, such as derivatives of aniline (found in dyes, marking pens, and shoe polish) and toluidine (found in pesticides and shoe polish). Exposure to these chemicals is usually work-related. Hemorrhagic cystitis caused by these derivatives is self-limiting, and cessation of the exposure usually suffices for cure. Exposure also increases the risk of transitional cell carcinoma. Thus, the workup for gross hematuria should reflect this possibility. [42]

Viral causes of hemorrhagic cystitis

Patients undergoing therapy to suppress the immune system—eg, after solid organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—are at risk for hemorrhagic cystitis due to either the direct effects of chemotherapy or activation of dormant viruses in the kidney, ureter, or bladder. [35, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]

In the early 1990s, infection with polyomavirus or adenoviruses was implicated as the likely etiology of this condition. The BK virus (polyomavirus) subclinically infects most of the population in childhood and persists indefinitely in the kidney after primary infection. When the immune system is compromised, as in persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or those undergoing chemotherapy or chemical immunosuppression, the virus can be reactivated, leading to clinical nephritis, ureteritis, or cystitis. [54]

The BK polyomavirus [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65] and adenovirus types 7, 11, 34, and 35 [66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73] have been the most commonly described viruses in these cases. Cytomegalovirus, [74, 75] JC virus, [76] and herpesviruses [35, 77, 78] have also been identified as causative agents in these scenarios.

In the pediatric population, the species most commonly isolated is adenovirus type 11, which has a propensity for the urinary tract. It reactivates with profound immunosuppression. It is also the most common cause of hemorrhagic cystitis in the healthy child.

HIV itself does not cause hemorrhagic cystitis, but immune suppression from HIV infection can predispose to other viral infections, such as BK virus, leading to the condition. [79] BK virus has also been suggested to be a causal transforming agent for bladder cancer. [80]

Epidemiology

Hemorrhagic cystitis occurs in up to 70% of patients exposed to high doses of cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide chemotherapy. [81, 82, 83, 84] and in 5-10% of patients who undergo pelvic irradiation to treat malignancy. [6, 7, 8, 85] The incidence in the pediatric population is less than that in adults.

A study in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation found a 2-year cumulative incidence of 24% for BK polyomavirus–associated hemorrhagic cystitis. These researchers identified three clinical factors associated with hemorrhagic cystitis in these patients: myeloablative conditioning, cytomegalovirus viremia, and severe acute graft versus host disease. [86]

In a study of 33 haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients, 20 developed hemorrhagic cystitis during a mediian follow-up of 38 days, and the cumulative incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis at day 180 was 62%. Factors significantly associated with the development of hemorrhagic cystitis were previous transplant and the occurrence of cytomegalovirus reactivation before hemorrhagic cystitis. [87] In another study of 1321 allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients, 219 (16.6%) developed hemorrhagic cystitis at a median of 22 days. [88]

A review of consecutive pediatric patients treated at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1986 to 2010 found that hemorrhagic cystitis was observed in 97 of 6,119 children (1.6%). On univariate analysis, the following factors were significantly associated with increased risk of hemorrhagic cystitis [89] :

-

Age > 5 years

-

Male gender

-

Cyclophosphamide or busulfan chemotherapy

-

Bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation

-

Pelvic radiotherapy

-

Underlying diagnoses of rhabdomyosarcoma, acute leukemia, or aplastic anemia

Factors associated with greater severity of cystitis were as follows [89] :

-

Older age

-

Late onset of hemorrhagic cystitis

-

Positive urine culture for BK virus

-

Bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplantation

Prognosis

In general, cystitis caused by exposure to chemotherapeutic drugs can be expected to resolve after discontinuation of the agent and treatment with irrigation/fulguration. Conversely, hemorrhagic cystitis due to pelvic radiation therapy tends to recur for months, or even years, after completion of radiotherapy. Seemingly minor events, such as urinary tract infection or bladder distention, may trigger florid hemorrhage. Close follow-up with periodic urinalysis and urine culture and sensitivity testing, along with aggressive management, may prevent recurrences.

The prognosis in pediatric patients with hemorrhagic cystitis is related to successful treatment of their primary oncologic condition. Most patients are successfully treated, with a resolution of hemorrhagic cystitis. However, long-term effects on the bladder may include increased bladder fibrosis, reduced bladder capacity, and upper tract deterioration.

In a retrospective single-instiution study of children who developed hemorrhagic cystitis after bone marrow transplantation, Au et reported high mortality and significant genitourinary morbidity. Factors associated with higher mortality included Foley catheterization, need for dialysis, and BK viremia. [90]

Complications are unusual in patients with chemical cystitis. Wound problems, urinary anastomotic strictures and leaks, and bowel anastomosis problems are more common in patients who have undergone a urinary diversion procedure after radiation therapy. [91, 92] Patients with severe hemorrhagic cystitis refractory to medical intervention are at an increased risk for mortality.

-

Changes associated with irradiation cystitis, which developed after 7200cGy external beam radiation for localized prostate cancer.

-

Neovascularity associated with irradiation cystitis. When distended, these weak-walled vessels often rupture, resulting in submucosal hemorrhage and gross hematuria.

-

Bladder neck neovascularity after radiation therapy (IMRT) for prostate cancer.

-

Diagnosis algorithm. R/O = rule out; US = ultrasonography; VUR = vesicoureteral reflux.

-

Management of hemorrhagic cystitis. PCN = percutaneous nephrostomy.

-

Grading of hemorrhagic cystitis.