Background

Primary gastrointestinal (GI) neoplasms in children are rare. [1] In 1960, the incidence of GI malignancies arising from the bowel was estimated at less than 1% of pediatric tumors, and most of the diagnoses were made during urgent exploration for an abdominal crisis. This is in contrast to adults, in whom 22% of malignancies are located in the GI tract; furthermore, most adults have long-standing symptoms (eg, pain, weight loss, and bleeding). Like other pediatric cancers, those of the GI tract differ from corresponding cancers in adults in terms of histology, pathogenesis, and clinical presentation. [2]

Much of the pediatric literature regarding GI malignancies consists of case reports. Consequently, this article focuses on the more common benign and malignant neoplasms of the GI tract in children, in addition to information gleaned from the relatively sparse literature.

Esophageal Neoplasms

Benign and malignant smooth-muscle tumors of the esophagus in children account for fewer than 5% of all leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. Tumors in the pediatric population, in contrast to those in adults, are multiple; localized tumors represent only 9% of cases. In children, these tumors are more commonly found in girls than in boys.

Presenting symptoms include dysphagia, retained food, and chest pain. Barium swallow reveals proximal dilation that is easily confused with achalasia. Esophagoscopy reveals a mucosa-covered narrowing; biopsy is diagnostic. The treatment for symptomatic lesions is surgical resection, which often requires esophageal replacement because of the diffuse nature of the disease. [3] One series reported that only 11% of leiomyomas were amenable to enucleation. [4]

Children with long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are at risk for developing Barrett esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma in a progression similar to that seen in adults. [5, 6, 7, 8] In one reflux series, 13% of children who underwent surveillance endoscopy and biopsy were found to have Barrett esophagus. Children born with esophageal atresia may be at increased risk for the development of Barrett esophagus. [9]

In view of the small number of pediatric cases of Barrett esophagus reported in the literature, surveillance and treatment are based on adult recommendations. Every patient needs aggressive medical treatment. Cases that have advanced to metaplasia should be seriously considered for antireflux procedures. High-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma of the esophagus requires esophagectomy and gastric pull-up or bowel interposition for reconstruction.

Gastric Neoplasms

Gastric teratomas comprise fewer than 1% of all childhood teratomas. Clinical presentation generally occurs within the first 3 months of life as an abdominal mass, abdominal distention, emesis, GI bleeding, anemia, and respiratory distress. Teratomas in this location occur predominantly in males (96%); no cases of malignant transformation have been reported.

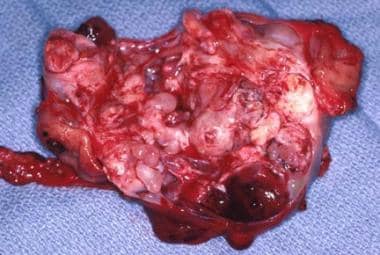

Diagnosis is made with ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), or both; these modalities reveal the characteristic heterogenous appearance, including fat, calcifications, and cystic areas. Most cases are treated with simple resection (see the images below), but partial gastrectomy may be necessary.

Gastric cancer is rare in the pediatric population. [10] Gastric carcinoma accounts for only 0.05% of GI malignancies in childhood. Symptoms are often similar to those of peptic ulcer disease and include pain and vomiting. The diagnosis is made by upper endoscopy with biopsy or upper GI contrast series.

Because of the rarity of this lesion, recommendations for therapy are based on the adult literature. The first step is to determine if the child is an operative candidate. CT and intraesophageal US both are useful in determining the extent of disease. Complete or partial gastrectomy may be performed with resection of surrounding lymph nodes; however, the overall prognosis is poor. Surgical resection with or without concomitant chemotherapy and radiation may prolong survival, but mortality remains high.

Gastrointestinal Lymphoma

Lymphoma is the most common small-bowel malignancy in the pediatric age group. In one of the larger series, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) accounted for 74% of alimentary tract malignancies. [11, 12] (See the image below.) Tumors were found in the colon (50.9%), small bowel (21.8%), and stomach (1.8%). Many other series identify 50-93% of patients who have primary intestinal lymphomas located in the ileocecal region.

The most common histologic subtype of these tumors is Burkitt lymphoma, which accounts for as many as 75% of the lesions. Correct preoperative diagnosis rarely occurs, and laparotomy with tissue evaluation is used for diagnosis.

Patients generally have a history of nonspecific chronic abdominal pain and present urgently with an acute exacerbation caused by intussusception (46%), appendicitis (22%), perforation (11%), or bowel obstruction (8%). Physical examination may reveal occult blood per rectum, a palpable abdominal mass, or both. CT and MRI may be useful in cases where clinical suspicion is high. [13] If the diagnosis is made preoperatively, a bone marrow biopsy is performed to rule out metastatic disease. Otherwise, this study is required after laparotomy as part of the staging of the lymphomatous disease.

Surgical management of GI NHL depends on the stage of disease at presentation. Tumor burden is the most reliable prognostic factor. Bulky disease can rarely be completely resected, and aggressive debulking has not shown a survival benefit. In these cases, surgery should be limited to evaluating the extent of disease and obtaining adequate tissue for diagnosis, followed by intensive multiagent chemotherapy. Perforation has been described as a potential complication of rapid regression of the tumor from the bowel wall secondary to chemotherapy. [14]

In cases of localized disease, complete surgical resection includes removal of the primary tumor and thorough examination of mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and para-aortic lymph nodes to assess for metastatic disease. Complete surgical resection is followed by a histopathologically specific chemotherapy protocol, but the duration and intensity of therapy are decreased because the stage is lower.

Carcinoid Tumors

Carcinoid tumors are derived from enterochromaffin cells located throughout the GI tract. Overall, carcinoids are most commonly found in the ileum (30%), the appendix (30%), and, less frequently, the remaining intestine. Enterochromaffin cells are not usually present in the GI tract until after age 4 years; thus, most carcinoids in children occur after age 5 years. The yearly incidence of carcinoid tumors occurring in children aged 10-15 years is 0.4-0.8 per 100,000 population.

Most children present with symptoms of acute appendicitis, which are likely caused by luminal obstruction by the tumor. [15] Rarely, carcinoids first manifest with carcinoid syndrome, an indication of metastasis to the liver or beyond. This consists of flushing, tachycardia, diarrhea, and asthma secondary to release of serotonin, substance P, or other vasoactive mediators that do not pass through hepatic deactivation before entering the systemic circulation.

In these cases, diagnosis is confirmed by finding elevated urinary levels of 5-hyroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), which is a metabolite of serotonin. If 5-HIAA is elevated, further localization of the tumor is possible through the use of CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Appendiceal carcinoids are almost never metastatic, but 70% of ileal and cecal carcinoids metastasize. The distinction between benign and malignant tumors is the presence of metastasis rather than histologic features.

Appendiceal carcinoids smaller than 2 cm are treated with a simple appendectomy. [15] Tumors larger than 2 cm have a higher frequency of metastasis and are treated with a right hemicolectomy. Treatment of small-bowel carcinoids requires wide resection and regional lymph node sampling. At the time of surgery, an intense yellow appearance aids in the diagnosis, and care is taken during surgery because carcinoid crisis can occur from sudden release of vasoactive mediators.

Overall survival in children is excellent, especially for the common smaller (< 2 cm) carcinoids of the appendix.

Polypoid Disease of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Juvenile polyps (see the image below) are the most common type of neoplasm in the GI tract, accounting for 80% of polyps in children. Grossly, the polyps appear beefy red and range in diameter from several millimeters to several centimeters. Histologically, these lesions represent benign hamartomas and have no malignant potential.

Juvenile polyps commonly manifest as painless rectal bleeding in toddlers but may manifest with prolapse (4%) or abdominal pain (10%). [16] Diagnosis is made through a thorough history, rectal examination, sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, and/or a contrast enema (generally an air/contrast enema; see the image below).

The barium enema of the patient with familial polyposis. Note the multiple filling defects throughout the colon.

The barium enema of the patient with familial polyposis. Note the multiple filling defects throughout the colon.

Polyps in the distal colon and rectum are easily resected via endoscopic polypectomy. [17] More proximal lesions are resected endoscopically, rarely with colotomy and polypectomy, or are left to slough spontaneously if adequate visualization of the entire colon demonstrates fewer than five polyps, thus excluding the diagnosis of juvenile polyposis syndromes. If five or more polyps are identified, complete excision of all polyps is preferred, either via colonoscopy or surgical excision with multiple enterotomies for less accessible lesions. This eliminates the problem and yields tissue to correctly characterize the polyp type.

Juvenile polyposis syndrome is a dominantly inherited disorder that can occur as diffuse juvenile polyposis of infancy (0-3 months), diffuse juvenile polyposis (6 months to 5 years), and juvenile polyposis coli (5-15 years). Presenting signs include diarrhea, rectal bleeding, intussusception, anemia, prolapse, and failure to thrive. The diagnosis is made by using the same diagnostic modalities discussed above, and the presence of five or more polyps in sporadic cases or one polyp in cases with a family history confirms the diagnosis.

These children are at high risk for malignancy (17%) occurring by the fourth decade of life and need long-term surveillance. Many surgeons recommend prophylactic colectomy and rectal mucosectomy with endorectal pull-through as the primary treatment for this disease as soon as the diagnosis is established.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, another autosomal dominant disease, is characterized by the presence of intestinal polyps with mucocutaneous pigmentation of the mouth, hands, and feet. Polyps may be found anywhere from the stomach to the rectum, with most occurring in the small bowel. The polyps are classified as hamartomas of the muscularis mucosa. Patients without a family history often present with cramping abdominal pain caused by intermittent intussusception of a polyp. These patients have an increased risk of cancer with transformation of hamartomas into carcinomas. Extraintestinal (eg, ovarian, cervical, and testicular) tumors are also associated with this syndrome.

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is diagnosed on the basis of family history, pigmented spots, and cramping abdominal pain. Recommendations for treatment consist of annual physical examinations, complete blood count (CBC), breast and pelvic examinations, testicular examinations with US, and pancreatic US. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy are recommended every 6 months. Polyps larger than 5 mm are removed during colonoscopy. Small-bowel polyps larger than 1.5 cm are surgically resected, with intraoperative endoscopy used for localization if necessary.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant cancer predisposition syndrome characterized by more than 100 visible adenomatous polyps in the colon. It is caused by germ-line mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene.

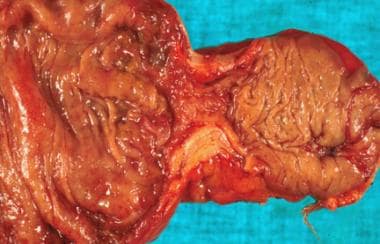

Patients present with rectal bleeding, anemia, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Most cases are diagnosed on routine screening of children from an affected family. Increasingly, at-risk patients can be identified with molecular diagnostics (ie, screening for APC mutations). Diagnosis is established by sigmoidoscopy, which reveals a colon carpeted with polyps. Polyps occur anywhere along the GI tract, but most of the adenomatous polyps are in the colon. The risk for developing malignancy is 100%. Therefore, surgical resection of the entire colon is necessary. (See the images below.)

Surgical specimen of the colon in a patient with familial polyposis after total colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Note the carpetlike appearance of the mucosa covered with polyps.

Surgical specimen of the colon in a patient with familial polyposis after total colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Note the carpetlike appearance of the mucosa covered with polyps.

Operative options for FAP include total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, which requires frequent surveillance of the rectal stump, and restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA), which has shown good long-term results in function and quality of life. [18, 19] Annual upper and lower endoscopy is recommended in all patients. Resection of remaining polyps should be performed for polyps larger than 1 cm, rapidly enlarging polyps, or polyps with severe dysplasia.

Gardner syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder described as the association between colonic FAP and multiple osteomas, fibromas, and epidermoid cysts. The natural history and treatment of the colonic polyps mimics that for patients with FAP. Turcot syndrome is the association of colonic FAP and brain tumors.

Lymphoid polyps are pseudopolyps of submucosal intestinal lymphatic tissue secondary to hyperplasia due to nonspecific infectious causes. These polyps may ulcerate and erode the overlying mucosa, bleed, and cause chronic anemia. Colonoscopy and contrast enema, individually or in combination, are the diagnostic modalities of choice. The appearance of these polyps on either technique shows a morphologic distinction from juvenile or adenomatous polyps. No treatment is necessary, and therapy is directed toward eradicating the underlying infectious process.

Esophageal polyps in children are rare (0.14%) and are believed to be related to mucosal injury (eg, from GERD or esophagitis). [20, 21] Patients most often present with vomiting, abdominal pain, and bleeding. Diagnosis is made by means of endoscopy and biopsy. Treatment options include antacid therapy, as well as antireflux surgery or polypectomy.

Colorectal Carcinoma

Colorectal carcinoma is the most common colonic malignancy in children and occurs with an incidence of 1.3-2 cases per million population. Predisposing factors are noted in 10-25% of childhood colorectal cancers, and the rest arise spontaneously. The two main premalignant conditions giving rise to colorectal cancers are as follows:

-

Polyposis syndromes

-

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

The risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum in ulcerative colitis is 3% during the first 10 years of disease, and this increases 10-15% in each subsequent decade. Patients with Crohn disease have a cancer risk 20 times higher than the general population and require regular surveillance and random biopsies.

In the sporadic type of colorectal cancers, the predominant histologic type appears to be mucinous adenocarcinoma (as shown below), occurring in up to 80% of patients. Mucinous adenocarcinoma is associated with the worst prognosis. Children present with nonspecific abdominal symptoms, including cramping abdominal pain, vomiting, and rectal bleeding. Workup includes barium enema, colonoscopy, and CT.

Surgery was performed for colonic obstruction in a child. A stricture is demonstrated here at the time of resection, and the pathology reveals mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Surgery was performed for colonic obstruction in a child. A stricture is demonstrated here at the time of resection, and the pathology reveals mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Most children with mucinous adenocarcinoma present with advanced disease secondary to delay in diagnosis. In one of the larger series, because of the predominantly aggressive mucinous histology, complete resection was achieved in only 30% of children. Surgery with the intent to cure consists of a radical resection of the portion of colon involved, its mesentery, and the surrounding lymphatics. Palliative therapy includes permanent colostomy to relieve obstruction. Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation are used, but very little survival benefit has been demonstrated. The 5-year survival rate ranges from 5% to 28%, and this directly correlates with the completeness of resection.

-

An intraoperative view of a gastric teratoma being resected.

-

The gross specimen of a gastric teratoma after resection. Note the heterogeneity of the tumor.

-

A non-Hodgkin lymphoma present in the mid jejunum at the time of resection.

-

The transanal appearance of a child with familial polyposis before resection.

-

Surgical specimen of the colon in a patient with familial polyposis after total colectomy with ileoanal anastomosis. Note the carpetlike appearance of the mucosa covered with polyps.

-

The barium enema of the patient with familial polyposis. Note the multiple filling defects throughout the colon.

-

Operative view of a pedunculated juvenile polyp found in the mid jejunum.

-

Surgery was performed for colonic obstruction in a child. A stricture is demonstrated here at the time of resection, and the pathology reveals mucinous adenocarcinoma.