Practice Essentials

The lymphatic system is an important component of the immune system. It includes the lymphatic fluid, lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, adenoids, Peyer patches, and thymus. Lymphatic fluid consists of an ultrafiltrate of blood collected within lymphatic channels, which run throughout the entire body. The fluid is slow-moving and is transported from the head and extremities to larger vessels, which then drain into the venous system. Along these channels reside approximately 600 lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes are composed of follicles and contain an abundance of lymphocytes. Lymph is filtered through the lymph node sinuses, where particulates and infectious organisms are detected and removed. Because of the exposure to immune challenges, antibody and cell-mediated immunity is mediated. As a result of such normal processes, the lymph nodes can enlarge through either proliferation of normal cells or infiltration by abnormal cells.

Lymphadenopathy is defined as the enlargement of one or more lymph nodes as a result of normal reactive process or a pathologic occurrence. [1] Whereas the (increased) size of the lymph node is the most common reference, an abnormal number or alteration in consistency may suggest a pathologic change that requires investigation and possible intervention.

Clinicians are challenged with the task of differentiating "true" enlarged lymph nodes related to a pathologic process from what are often referred to as "shotty" lymph nodes. Shotty lymph nodes are small mobile lymph nodes in the neck that are palpable and usually represent a benign change, commonly associated with viral illness.

The removal of lymph nodes to determine the etiology of their enlargement has been practiced for many years, but it is unknown when it was first performed. This procedure is often performed by general adult and pediatric surgeons, as well as by surgical specialists such as otolaryngologists. Because children often present with enlarged lymph nodes, pediatric surgeons are often the ones who treat these children, either primarily or as a referral.

A child with an enlarged lymph node is a common situation faced by clinicians. The challenge is to satisfy the parents' fears of malignancy and to do so in a safe, timely, and cost-effective manner. Organizing the possible causes of lymphadenopathy by anatomic location and origin aids the clinician in the evaluation. This article provides a rational approach to determining the etiology of the lymph node disorder, highlights various disorders to consider in treating a child with lymphadenopathy, and discusses various means of obtaining a tissue diagnosis when the cause of lymphadenopathy is uncertain.

Anatomy

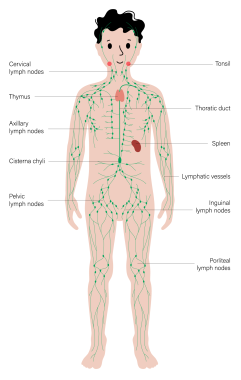

Lymph node distribution

Lymph nodes are organized in groups that drain specific regions of the body. This knowledge guides the clinician to inspect particular areas of anatomy when lymphadenopathy occurs.

Lymphatic drainage of the head and neck is traditionally divided into six regions. The most important nodes in this grouping are around the internal jugular lymph nodes. The superior aspect is termed region II; it receives lymph from the supraglottic larynx, anterior nasopharynx, and oropharynx via submental and submandibular lymph nodes (region I). The middle portion of the internal jugular chain is region III; it collects drainage from the superior hypopharynx and superior larynx via direct drainage through lymphatic capillaries. The inferior part of the chain is region IV; it collects drainage from the inferior hypopharynx, inferior larynx, and thyroid and supraclavicular regions.

Region VI sits in the anterior aspect of the neck; it contains supraclavicular, pretracheal, and thyroid nodes, which drain into region IV. Region IV of the internal jugular chain is the common collecting point for regions I-III and VI. Region V collects lymph from the scalp and posterior nasopharynx. All lymphatic drainage from region V and region IV on the internal jugular chain collect into the jugular trunk (ie, a group of nodes positioned at the internal jugular anterior brachiocephalic veins) and subsequently into the thoracic duct on the left or directly into the brachiocephalic vein on the right.

The thoracic cavity maintains a distinct collection of lymph nodes, with a slightly complex drainage route that parallels bronchi, arteries, and veins. Each major bronchial division has a collection of nodes called the intrapulmonary lymph nodes, which lie within the lungs and drain each of the lung's corresponding segments. The intrapulmonary nodes drain into two sets of nodes, the left and right bronchopulmonary (hilar) lymph nodes, which are located at the junction of each lung and its main bronchi. These sets of nodes collect the lymphatic drainage from the segments of their respective lungs.

At the bifurcation of the trachea and beginning of each bronchus, three sets of nodes reside: the right and left tracheobronchial lymph nodes and the inferior tracheobronchial (or carinal) lymph nodes. An unusual feature of this anatomy is that the inferior tracheobronchial nodes collect lymph from the left lower lobe but drain that fluid into the right tracheobronchial lymph nodes. This is significant because a suspicious-appearing lymph node in the right hilar region should prompt evaluation of the left lower lobe and the right lung.

Aligned with the sides of the trachea are sets of nodes known as the right and left paratracheal lymph nodes, which collect lymphatic fluid from the right and left tracheobronchial nodes, respectively. The posterior thoracic cavity is drained via the intercostal lymph nodes and into the posterior mediastinal lymph nodes. The anterior thoracic cavity is drained through the parasternal lymph nodes, which are located next to the sternum in the intercostal space. The parasternal lymph nodes collect lymph from the anterior mediastinum and communicate with the medial aspect of the anterior chest wall.

The common drainage site for all of the aforementioned lymph nodes is into the jugular trunk and then into the thoracic duct on the left or directly into the brachiocephalic vein on the right.

The thoracic duct is the final common lymphatic drainage system for the lower extremities, the pelvis, the mesentery, most of the thoracic cavity, the left upper extremity, and the left head and neck. The thoracic duct is positioned on the right side of the aorta in the abdomen and receives lymph from the cisterna chyli. It ascends up through the thorax in the posterior mediastinum while receiving lymphatic drainage from the intercostal nodes. It crosses over to the left just below the carina and ascends to the level of the junction of the left internal jugular and left subclavian veins, where it connects into the venous system.

The upper intercostal nodes and right apical axillary nodes drain directly into the right brachiocephalic vein via the right bronchomediastinal trunk, and lymphatic drainage from the right side of the head and neck drain directly into the right brachiocephalic vein via the right jugular trunk.

The upper-extremity lymph node distribution consists of the cubital fossae and axillary region. The axillary group is subdivided into five subgroups. The lateral axillary subgroup drains the upper extremity and receives lymph from the posterior axillary subgroup, which in turn drains the posterior chest wall. The anterior axillary subgroup drains lymph from the anterior chest wall. The lateral and anterior subgroups drain into the central axillary subgroup, which in turn drains into the apical axillary (or subclavian) subgroup. The apical axillary nodes drain into the thoracic duct on the left or directly into the brachiocephalic vein on the right.

The intra-abdominal lymphatic drainage parallels the arterial system. Lymph nodes lie in the mesentery, adjacent to an arterial counterpart. Each artery has a cluster of nodes that receives lymph from its corresponding arterial supply: celiac, superior, and inferior mesenteric. These nodal groups eventually drain into the cisterna chyli, the beginning of the thoracic duct.

The additional role of the mesenteric lymphatic system is to absorb and transport long-chain fatty acids via chylomicrons. Intestinal mucosal immunity is primarily the responsibility of Peyer patches, which are unencapsulated collections of lymphatic tissue in lamina propria located on the antimesenteric side of the ileum. Mesenteric lymph nodes may become enlarged in mesenteric adenitis, a common cause of abdominal pain in children. A study that examined computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen showed that abdominal lymph nodes measuring up to 8 mm may be considered normal. [2]

The two groups that serve the lower extremities are the popliteal nodes and the inguinal nodes. The inguinal nodes are grouped into external and internal subtypes. The external subtype drains the lower extremity and lymph from the anterior abdominal wall and external genitalia. The internal inguinal nodes then drain into the external iliac nodes, which join the lymphatic drainage of the pelvis, via the internal iliac nodes, to come together in the common iliac nodes.

The two groups of common iliac nodes drain into the left and right lumbar nodes, beginning just proximal to the bifurcation of the aorta and eventually draining into the cisterna chyli, via left and right lumbar trunks. The cisterna chyli is the beginning of the thoracic duct. The kidneys and adrenal glands drain into lymph nodes around the renal vessels and subsequently into the lumbar nodes.

In most instances, lymph nodes up to 1 cm can still be considered normal. The two exceptions to this rule are the epitrochlear node, in which up to 0.5 cm is allowed, and the inguinal nodes, in which up to 1.5 cm is allowed.

Pathophysiology

Lymph nodes form part of the reticuloendothelial system, which encompasses various components involved in the body's defense mechanisms, including monocytes and macrophages in the blood and tissues, the thymus, the spleen, bone marrow, bones, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in organs, and the lymphatic vessels and fluid that move between tissues. [3]

Lymphadenopathy involves lymph node swelling, with its underlying mechanisms varying by cause. In response to infection or inflammation, an increase in lymphocytes and macrophages can enlarge the node. Alternatively, nodes may swell as a result of invasion by bacteria, viruses, cancerous cells, or other pathogenic agents. Lymph nodes, integral to the immune and lymphatic systems, filter antigens, leading to immune cell activation and potential node enlargement.

The type of immune cell predominance (eg, neutrophils or lymphocytes), can hint at the nature of the underlying infection (bacterial, viral, fungal), though other conditions (eg, lymphomas or autoimmune diseases) may also be relevant, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive clinical evaluation.

Etiology

Five broad etiologic categories lead to lymph node enlargement, as follows [4] :

-

Immune response to infective agents (eg, bacteria, viruses, fungi)

-

Inflammatory cells in infections involving the lymph node

-

Infiltration of neoplastic cells carried to the node by lymphatic or blood circulation (metastasis)

-

Localized neoplastic proliferation of lymphocytes or macrophages (eg, leukemia, lymphoma)

-

Infiltration of macrophages filled with metabolite deposits (eg, storage disorders)

Lymphadenopathy has been noted in the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children [5] (MIS-C; also referred to as pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome [PMIS], pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 [PIMS-TS], pediatric hyperinflammatory syndrome, and Kawasaki-like disease), which has appeared to correlate with COVID-19, though causing more severe symptoms. [6, 7] Further research into the possibility of a causal connection between MIS-C and SARS-CoV-2 is warranted.

Epidemiology

Lymphadenopathy is frequent in children, so much so that pinpointing its exact prevalence is challenging. Most cases are benign, with age playing a crucial role in its epidemiology. The probability of finding enlarged lymph nodes grows with age and exposure, making benign lymphadenopathy more commonly observed in children than in adults.

The prevalence of malignancy among children with lymphadenopathy managed in the primary care setting is approximately 5%; however, this figure rises to 13-49% among children with suspected malignancy who have undergone biopsy in pediatric referral centers. Malignant disease is often due to leukemia in younger children and to Hodgkin disease in adolescents. [8, 9]

The risk of malignancy increases with worrisome features such as systemic (B) symptoms (fever > 1 wk, weight loss > 10%, night-time sweating), fixed and nontender lymph nodes, lymph nodes having a diameter greater than 2 cm and not responding to antibiotic therapy, unusual locations (eg, supraclavicular or mediastinal), generalized lymphadenopathy, and unexplained abnormal laboratory results such as pancytopenia, persistently elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and highly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. [10]

Prognosis

Virus-associated lymphadenopathy

Most commonly, upper respiratory tract infections predominate as the source of lymphadenopathy. The nodes tend to be small, soft, and bilateral and do not have warmth or erythema of the overlying skin.

Cervical adenopathy is a prominent feature of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Posterior cervical nodes are most commonly involved, followed by the anterior cervical chain. Children with adenovirus-associated respiratory infections may present with generalized constitutional symptoms and bilateral cervical adenopathy. Treatment is based on controlling symptoms and preventing complications instead of providing specific antiviral therapies. [11]

Bacteria-associated lymphadenopathy

The two organisms most commonly associated with lymphadenopathy are Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. The clinical history often reveals a recent sore throat or cough, whereas the physical examination findings include impetigo, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, or acute otitis media. The primary sites involved include the submandibular, upper cervical, submental, occipital, and lower cervical nodal regions. Treatment involves administration of beta-lactamase–resistant antibiotics and drainage of purulence when fluctuation is present. [12]

Children who are hospitalized for a first episode of acute unilateral infectious adenitis generally do well. Younger patients and those with longer duration of node involvement before admission have an increased risk of surgical node drainage. [13]

Atypical mycobacteria

In the United States, atypical mycobacteria account for most cases of adenitis due to Mycobacterium infection. Numerous members are in this group, including Mycobacterium scrofulaceum and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. The onset of adenopathy may be relatively sudden; size may gradually increase over 2-3 weeks. The involved nodes usually have an overlying erythema and may be tender. The nodes may progress to fluctuance and ultimately drain spontaneously.

Treatment involves complete excision of the involved node because incision and drainage may lead to a chronically draining sinus. [14] Those dissections that may be adjacent to the marginal mandibular nerve are often associated with a transient paralysis that resolves over a few months. [15]

Mycobacterial tuberculosis

Lymph node involvement with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is commonly referred to as scrofula. It was previously a well-known manifestation of extrapulmonary tuberculosis; however, as tuberculosis has declined, so has the incidence of scrofula. Nonetheless, it is still prevalent in much of the world.

Patients with scrofula present with cervical node enlargement, most often around the paratracheal nodes or the supraclavicular nodes. Abnormal findings are observed on chest radiography in most cases. Clinical features are not helpful in distinguishing atypical from tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Nodal enlargement is usually painless; nodes are likely to suppurate and form sinuses. A tuberculin test is usually helpful. Treatment involves administration of rifampin and isoniazid. [16]

Cat-scratch disease

Cat-scratch disease is a zoonotic infection that originates from animal scratches, most likely cat or kitten scratches. The primary inoculation of the skin, eye, or mucosal membrane leaves a small papule that may or may not be evident upon examination. Indeed, the papule may resolve before the lymphadenitis appears. Patients usually have accompanying constitutional symptoms, such as fever, malaise, and fatigue. The causative agent is Bartonella henselae, a gram-negative rickettsial organism. The disease is usually self-limiting and requires only supportive treatment. Antibiotics may be warranted for protracted lymphadenopathy. [17]

Malignancies

Patients with lymphoma (Hodgkin disease [HD], non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL] [18] ), leukemia, or metastatic solid tumors may present with lymphadenopathy. The nodes are usually painless and continue to enlarge. Inflammatory signs or focuses are usually absent. Associated B symptoms of HD may be present, including fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise. If malignancy is suspected, a biopsy is needed to establish the diagnosis and allow important tests to be performed to guide therapy.

In a retrospective review by Oguz et al, children referred for concerning lymphadenopathy were more likely to have a malignant etiology if the lymph node was larger than 3 cm, the enlargement lasted longer than 4 weeks, supraclavicular involvement was observed, and abnormal laboratory and radiologic findings were noted. [19]

Other causes of adenopathy

Many less common disorders may also appear as lymphadenopathy.

In Kawasaki disease (ie, mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome), lymphadenitis is one of the earliest aspects of the disease. The enlarged node or group of nodes are unilateral, nonfluctuant, and usually located in the anterior triangle of the neck. Resolution of lymphadenitis is a rule. Kawasaki disease may closely resemble MIS-C, though the two conditions are distinct. [20]

Enlarged lymph nodes are prominent features in the course of sarcoidosis; the supraclavicular nodes and bilateral hilar nodes are involved.

Kikuchi lymphadenitis (ie, histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis) is a benign and rare disease of unknown origin that involves bilaterally enlarged cervical lymph nodes that are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. [21] Patients with Kikuchi lymphadenitis often have systemic symptoms, including fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and weight loss.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) often involves enlarged lymph nodes. Children with SLE tend to have more organ systems involved and a more severe course than adults with SLE do.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ie, histiocytosis X) is a syndrome with a broad clinical spectrum; its unifying pathologic feature is the derivation from Langerhans cells. The disease is believed to be a clonal neoplasm in which lymph node enlargement is common.

-

A preoperative radiograph showing a narrowed trachea secondary to an anterior mediastinal mass.

-

A CT scan showing an anterior mediastinal mass and compression of the trachea.

-

A CT scan showing an anterior mediastinal mass and compression of the left mainstem bronchus.

-

A lymph node biopsy is performed. Note that a marking pen has been used to outline the node before removal and that a silk suture has been used to provide traction to assist the removal.

-

A lymph node after removal by means of biopsy, which was performed completely under a local anesthetic technique.

-

A gross image of a node following excision. The cut surface of the node shows the typical fish-flesh appearance seen with lymphoma.

-

Pediatric lymph node distribution. Courtesy of Getty Images (Pikovit44).