Background

Ascites (Greek askites, derived from askos "bag, bladder") is defined as an abnormal amount of intraperitoneal fluid. (See the image below.) The condition has been recognized since antiquity. Ascites may consist of transudates (thin, low protein count and low specific gravity) or exudates (high protein count and high specific gravity). The etiology of ascites may differ among neonates and older children. The precise incidence of ascites in children is unknown, but the condition is rare.

Etiology

Biliary, urinary, and chylous ascites

Neonatal ascites is usually biliary, urinary, or chylous. In older children, trauma, infection, hepatocellular disease, pancreatic ascites, gynecologic or gastrointestinal (GI) abnormalities, neoplasia, and other miscellaneous causes predominate.

Biliary ascites in newborns is the result of spontaneous perforation of the bile duct, [1] usually at the junction of the common bile duct (CBD) and the cystic duct. The cause of these perforations is unknown; elevated intraductal pressure from a long common channel, congenital weakness of the wall of the duct, vascular insufficiency at the level of the ductal wall, and pancreatic reflux have all been proposed. Perforation of a choledochal cyst can be causative. Bile ascites in older children may occur as a result of trauma or after cholecystectomy.

Urinary ascites in neonates is usually due to intraperitoneal bladder or ureteric or upper-tract perforation as a result of distal obstruction. Posterior urethral valves (PUVs) are the most common cause [2] ; for this reason, males are affected much more often than females are. Complex urinary anomalies (eg, persistent cloaca) may allow reflux of urine through the genital tract into the peritoneal cavity, without the presence of a perforation. [3]

Chylous ascites may occur in neonates, [4, 5] with a slight male predominance. Neonatal chylous ascites is almost always idiopathic, but a congenital lymphatic abnormality is thought to be the usual underlying cause. Trauma (particularly nonaccidental trauma) with disruption of lymphatic ducts is well described in infants and older children. External compression of the lymphatics due to malrotation, hernia, intussusception, and neoplasia is another cause. Malignancy is an uncommon cause of ascites in children.

Other causes vary in incidence by age and geography. After the newborn period, infections such as tuberculosis are more frequent in underdeveloped areas, whereas hepatobiliary disease and neoplasia are more common in developed countries.

Miscellaneous causes of ascites in children

Hepatocellular disease (eg, storage disease, neonatal or viral hepatitis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency) may result in ascites. Evaluation and treatment of the underlying disease is essential. Paracentesis reveals the presence of fluid with a high serum-to-ascites albumin gradient (>1.1 g/dL) (see the Ascites Albumin Gradient calculator). Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis may complicate the course of the disease.

Cardiac abnormalities (eg, congestive failure, physiologic right-side heart obstruction, severe valvular regurgitation) may result in ascites.

Infection may lead to excess peritoneal fluid. Appendicitis is common in patients in developed countries, whereas tuberculous fluid collections and Salmonella organisms are observed in patients in the developing world.

Pancreatic ascites (either from trauma or pancreatitis) may occur in children. [6] Computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography (US) demonstrates the fluid and delineates the pancreatic anatomy. Paracentesis reveals fluid with markedly elevated amylase [7] and lipase levels.

Ascites may occur (particularly while the patient is in the neonatal intensive care unit [NICU]) as a result of iatrogenic gastric perforation from gastric catheters and/or tubes and with intraperitoneal feedings. Similarly, umbilical catheter perforation may result in the leakage of parenteral nutritional fluid into the peritoneal cavity.

Gastric adenocarcinoma, though quite rare in children, is also a possible cause of a presentation of ascites. [8]

Clinical Presentation

Fetal ascites may be identified during antenatal US. In the infant or child, the signs of ascites include shifting dullness to percussion, a fluid wave, and abdominal distention. An increased respiratory rate or frank respiratory distress may be the result of diaphragmatic elevation. The liver, spleen, or both may be apparent on ballottement. Signs of peritoneal irritation are usually absent, depending on the underlying etiology.

Plain radiography may demonstrate a diffuse glassy-hazy opacification, with separation of bowel loops. Findings on US confirm ascites. Paracentesis and analysis of the fluid are often necessary for a specific diagnosis.

Biliary ascites

Biliary ascites in neonates is rare. The usual clinical presentation is that of ascites with mild jaundice (direct hyperbilirubinemia), feeding intolerance, and a distended nontender abdomen. A small percentage of infants are more acutely ill, but most have a gradual progression of symptoms. Biliary ascites almost always occurs in infants younger than 3 months. Hepatobiliary scanning with iminodiacetic acid (IDA) demonstrates extraductal radionuclide in the peritoneal cavity. US is usually necessary to rule out congenital anomalies and obstructing lesions. Paracentesis reveals elevated bilirubin levels in the fluid.

Urinary ascites

Antenatal diagnosis of urinary ascites has been made with fetal US. Signs and symptoms of urinary ascites include abdominal distention, acidosis, elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels, and electrolyte abnormalities. Respiratory distress may be present, and in advanced cases, Potter syndrome may be present. This syndrome consists of a typical physical appearance due to oligohydramnios secondary to renal diseases. The oligohydramnios leads to abnormal lung growth and potentially fatal pulmonary insufficiency. Most patients are male and are younger than 1 month.

Urinary and abdominal US demonstrates the ascites and may help in identifying the underlying etiology. Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) should be performed, though the leak may not be identified. Paracentesis confirms the diagnosis via elevated creatinine levels in the fluid.

Chylous ascites

Chylous ascites is rare. Most cases occur in infancy, with a male predominance, and are of congenital origin. Signs and symptoms of chylous ascites are nonspecific and include abdominal distention and poor feeding.

US or CT may reveal the fluid (see the image below) and may help rule out underlying causes (eg, mesenteric cyst, tumor). The diagnosis is confirmed with paracentesis; the fluid has a markedly elevated triglyceride content (>1500 mg/dL) and a predominance of lymphocytes (>75%).

Treatment

Biliary ascites

Treatment of biliary ascites due to spontaneous perforation consists of drainage, either open or laparoscopic. Intraoperative cholangiography is performed through the gallbladder, and simple external drainage is used at the site of perforation. The perforation usually seals in a few weeks. The cholecystostomy tube can be left in place to verify ductal continuity and the absence of obstruction before the drain is removed. No attempt should be made to repair or reconstruct the duct.

Urinary ascites

Initial treatment is usually directed at relieving the associated obstruction to urinary outflow. It typically consists of urinary tract decompression, rehydration, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and administration of antibiotics. Catheter bladder drainage followed by cystoscopic ablation of the valves is indicated for PUVs. Drainage of the upper tract may be necessary in rare circumstances. Direct repair of the perforation site is usually unnecessary. [9, 10, 11]

Chylous ascites

After surgical causes (eg, malrotation, obstruction, neoplasia) have been ruled out with appropriate imaging studies, more than one half of patients respond to nonoperative treatment with parenteral nutrition and bowel rest for 2-4 weeks. Some authors advocate the initial use of diets rich in medium-chain triglycerides (eg, Portagen) rather than complete bowel rest. If the fluid is compromising respiration, aspiration may be necessary .

If the chylous ascites is refractory to nonsurgical treatment—that is, if it fails to resolve after the patient has taken nothing orally (nil per os [NPO]), has received total parenteral nutrition [TPN]), or both for 6 weeks—or if a surgically correctable underlying cause is identified, exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy is necessary. [12] Administration of a high-fat diet or whole milk with Sudan dye immediately before surgery may help in identifying the site of leakage. [13]

Although the site may be anywhere in the retroperitoneum or mesentery, the most common location is the base of the superior mesenteric vessels. Ligation of the leak site with the use of fibrin glue is performed. Laparoscopic placement of fibrin glue and mesh has been reported. [14] If direct repair fails, a peritoneovenous shunt may be needed. [15] These must often be individually customized for infants.

A small retrospective study (N = 6) by Moussa et al described the successful use of intranodal lymphangiography and lymphatic embolization to manage iatrogenic chylous ascites in children for whom conservative management has failed. [16]

Idiopathic neonatal chylous ascites is associated with a high mortality.

Miscellaneous causes of ascites

Treatment of the ascites caused by hepatocellular disease consists of sodium and fluid restriction and diuretics (usually spironolactone). Repeated therapeutic paracentesis may be necessary.

Sarma et al carried out a prospective longitudinal observational study aimed at assessing the safety, complications, and outcomes of large-volume paracentesis (with or without albumin therapy) in children with severe ascites due to chronic liver disease. [17] They found that the procedure was safe in all age groups, that it was best performed under albumin coverage, and that volume extraction should be restricted to less than 200 mL/kg actual dry weight.

Long-term management of ascites from hepatocellular disease may require the placement of a peritoneovenous shunt. [18, 19, 20] In a series of 11 patients with ascites from various etiologies, 10 patients experienced resolution after shunting. [21] A series of children (mean age, 3 y) from Great Ormand Street with peritoneovenous shunts over a period of more than 30 years were reviewed. Approximately one third had shunt-related complications, mostly minor. Over 90% success in resolution of the ascites was obtained. [22]

Management of ascites due to cardiac abnormalities is directed at the underlying lesion.

Treatment of ascites resulting from infection is directed at the underlying condition.

For pancreatic ascites, bowel rest and TPN are the recommended initial measures, along with the administration of somatostatin analogues. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), with or without nasopancreatic transampullary stenting, is the usual initial treatment. Exploration and repair may be required if medical management fails.

Treatment of ascites of iatrogenic origin usually involves exploration and repair of the injury site.

-

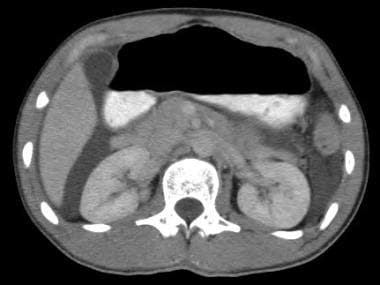

CT demonstrates free intraperitoneal fluid due to urinary ascites.

-

Massive ascites.