Background

Many of the anomalies encountered in pediatric urologic gynecology result from problems related to abnormal embryogenesis of the urinary and genital tracts. Given the close association between the development of the urinary and genital systems, disorders observed in one may be a harbinger for an anomaly of the other.

Today, most urogynecologic disorders are detected even prior to birth with antenatal ultrasonography (US). Most of the remaining abnormalities are detected during infancy or childhood as the result of urinary tract infections (UTIs), urinary incontinence, or abnormalities (eg, interlabial mass, otherwise abnormal-appearing external genitalia) detected on physical examination. [1] Some urogenital malformations, however, are more elusive and only become evident later in life when a clinical problem arises.

Because congenital abnormalities result from abnormal embryogenesis, beginning with a brief overview of healthy female embryology is appropriate.

Female embryology

Congenital abnormalities commonly involve the urinary and genital tracts. An understanding of normal embryogenesis is a prerequisite for understanding congenital abnormalities.

Marshall [2] and Stephens et al [3] provided a detailed discussion of the embryology of the lower urinary tract. The divergence of normal sexual differential into male and female phenotypes begins in week 9 of gestation. In the absence of a Y chromosome, the gonads develop into ovaries rather than testes. As a result, the wolffian system regresses because of an absence of androgen production, and the müllerian ducts form the fallopian tubes, the uterus, and the proximal part of the vagina. Formation of the female genital tract also depends on the partition of the cloaca, first by the urorectal septum and then by the urogenital septum.

Congenital Urogynecologic Anomalies

Bladder exstrophy and female epispadias

The incidence of bladder exstrophy is 1 per 30,000 live births and is lower in females than in males. It is part of a continuum of developmental anomalies that result from a persisting cloaca or an abnormally large cloaca that does not retract normally toward the perineum. Bladder exstrophy is a more severe anomaly, whereas epispadias is a less severe variant of the exstrophy-epispadias complex.

The initial management of bladder exstrophy involves covering the exposed bladder with a nonocclusive dressing (eg, plastic food wrap) to protect the bladder plate. To prevent unnecessary trauma, ligating the umbilical cord with silk ties rather than a plastic or metal clamp is best. Some children with bladder exstrophy develop functional bladder capacities, whereas others go on to develop small and poorly compliant bladders. The reason for this is not completely understood.

The surgical management of bladder exstrophy involves bladder closure within the first days of life. Bladder enhancement and bladder diversion are surgical options later. Bladder-neck reconstruction may be performed at the time of bladder closure or in a staged fashion. [4, 5, 6, 7] Continence rates range from 43% to 87%. [8, 9, 10]

In the female with bladder exstrophy (see the image below), the mons pubis is absent. The clitoris is bifid and may be separated by considerable distance. The anterior labia are laterally displaced and fuse in the midline posteriorly. The vagina and introitus are also displaced anteriorly relative to their usual position.

The introitus is stenotic in some cases, but the internal genital structures (uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes, ovaries) are typically unaffected. The ureters insert into the bladder plate laterally. Therefore, following exstrophy closure, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is almost universal and may predispose to UTIs. Another issue that may affect women who have undergone prior exstrophy closure is uterine prolapse because of resulting deficient pelvic floor support.

Female epispadias (see the image below) may vary in presentation depending on the severity of the urethral defect. In complete epispadias, incontinence is caused by (1) a foreshortened and widened urethra, (2) a partially absent external urethral sphincter, and (3) a poorly developed bladder neck. Treatment is directed at reconstruction of these deficient structures and at ureteral reimplantation proximal to the reconstructed bladder neck region. [11, 12]

Cloacal exstrophy

The incidence of cloacal exstrophy (see the image below) is 1 per 200,000 live births and is much lower in females than in males. This condition is the most severe manifestation of developmental abnormalities related to the exstrophy-epispadias complex. In cloacal exstrophy, the bladder plate is divided in half by the hindgut. The ileum enters and intussuscepts into the middle of the hindgut, creating an "elephant trunk" deformity.

This and other associated anomalies, including omphaloceles, spinal dysraphism, and orthopedic anomalies, mandate a multidisciplinary approach to the reconstruction of bladders in these children. [13] The treatment of storage abnormalities of the bladder usually involves bladder augmentation with intestinal segments. Clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) may also be required to maintain urinary continence.

Urogenital sinus anomalies

Urogenital sinus anomalies occur when the urethra and the vagina both open into a common channel rather than into separate orifices on the perineum. Abnormal formation of the urogenital septum is believed to cause this rare anomaly.

The examiner may note the presence of two orifices on the female perineum, one representing the urogenital sinus and the other the anus. If only one orifice is noted, the malformation is referred to as a cloaca or cloacal malformation. In this scenario, the urethra, vagina, and rectum all join a common channel before exiting the perineum. Although most urogenital sinus anomalies occur in association with differences (disorders) of sex development (DSDs, also referred to as intersex disorders; see below), they may also occur as a separate entity.

Patients with urogenital sinus anomalies are evaluated soon after birth to delineate their anatomy and to exclude a DSD. Infants may present with a dilated vagina, possibly resulting in an abdominal mass, if the posterior lip of the hymen causes partial obstruction and retention of urine (hydrocolpos). Beyond infancy, the anomalies may be discovered because of a UTI or when the urethral meatus cannot be located when catheterization is attempted. Less commonly, vaginal abnormalities are detected at menarche, upon failure to menstruate or upon pain caused by sequestration of menstrual fluid.

Classification of urogenital sinus anomalies is difficult because of the tremendous anatomic variability. Anatomy is typically determined by means of fluoroscopy (genitography), genitoscopy, or both. Reconstructive options and outcomes are directly related to the location of the confluence of the vagina and urethra. [14, 15] Patients with a low confluence typically fare better in terms of both continence and cosmesis than do patients with high confluence.

Vaginal agenesis and Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome

Agenesis of the vagina in genetic females may be accompanied by various other defects in the genitourinary (GU) tract. Most patients present in adolescence with amenorrhea or pain, but young girls may also present with UTI or hydrocolpos. Genital defects include the spectrum of vaginal agenesis alone to agenesis of the uterus and fallopian tube. These genital defects are associated with (ipsilateral) renal agenesis. Some patients present after urethral intercourse leading to stress urinary incontinence due to overstretching of the sphincter mechanism.

Treatment of the Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome (also referred to as Mayer-Rokitansky syndrome or Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome) includes dilation, vaginoplasty, or neovaginal reconstruction with bowel. [16, 17, 18]

Ectopic ureters

An ectopic ureter results when the ureteric bud develops more cranially than usual from the mesonephric duct. These ureters are more caudally positioned than a normal ureter and are two to three times more common in females than in males.

More than 85% of females with ectopic ureters have duplex systems, whereas most in males are singlets. In girls, ectopic ureters usually insert into the urethra, the vestibule, or the vagina. When duplex, the ectopic ureter typically subtends the upper-pole renal moiety. The upper pole usually has poor function, depending on the degree of obstruction or renal dysplasia. The lower renal moiety ureter often has VUR.

Incontinence is common in girls with an ectopic ureter. Unlike in boys, an ectopic ureter in girls may insert distal to the urethral sphincter. As a result, these patients may present with constant urinary leakage that is usually of small volume. This condition should be strongly suspected in the girl whose has persistently damp underwear.

An ectopic upper-pole ureter may join the lower end of the remnant mesonephric duct system comprising Gartner ducts. These ureters are associated with nonfunction of the associated renal moiety and may result in the formation of cystic dilatation of the Gartner duct, with eventual rupture of the cyst and drainage into the vaginal opening. Drainage of fluid or pus into the vagina prompts further investigation.

Renal and pelvic US may show a dilated or abnormal upper-pole renal moiety, and a cystic structure may be observed in the pelvic or vaginal area. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in further delineating the anatomy, and findings on retrograde fluoroscopic studies are diagnostic if the often-elusive ectopic orifice can be identified. Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) appears to be highly accurate for diagnosing ectopic ureter in incontinent girls. [19, 20]

Appropriate treatment of ectopic ureters depends primarily on where the ureter inserts and the function of the renal moiety it subtends. Ectopic upper-pole ureters to the genital tract may be treated with simple upper-pole nephrectomy. [21] However, if they insert into the urinary tract and are associated with reflux, then ureterectomy, in addition to heminephrectomy, may be needed to prevent postoperative urinary reflux and infection. An ectopic ureter subtending a renal moiety that has preserved function can be treated with ureteral reimplantation.

Differences (disorders) of sex development

A complete description of the array of DSDs is beyond the scope of this article; however, urologists and gynecologists must be familiar with the more common disorders whereby gender assignment and rearing is along female lines. [22] These conditions include normal-appearing girls who are genetically male (46,XY DSD; previously referred to as male pseudohermaphroditism) and genetic females appearing as males (46,XX DSD; previously referred to as female pseudohermaphroditism).

Persons with a 46,XX DSD are genetic females but may appear as males without testes. The most common cause of this DSD is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (21-hydroxylase deficiency in >90%). In this disorder, the absence of 21-hydroxylase results in the overproduction of androgens and results in a wide spectrum of genital abnormalities, ranging from mild masculinization of the clitoris (clitoromegaly; see the image below) to complete masculinization.

46,XX difference (disorder) of sex development (female pseudohermaphroditism). Note clitoromegaly and small introitus.

46,XX difference (disorder) of sex development (female pseudohermaphroditism). Note clitoromegaly and small introitus.

The labioscrotal folds are rugous and hyperpigmented, producing the physical appearance of severe hypospadias with cryptorchidism; however, in all cases, the internal female anatomy is normal. After the diagnosis is established, surgical treatment involves feminizing genitoplasty (eg, reduction clitoroplasty, vaginoplasty, labioplasty).

Persons with a 46,XY DSD are genetic males but may appear as females. Testicular feminization is the most common cause of this DSD. Testicular feminization results from androgen insensitivity. The diagnosis should be suspected in all girls with inguinal hernias. The hernia sacs may be found to contain testes. In addition, the diagnosis of 46,XY DSD should always be suspected in adolescent girls with normal development and primary amenorrhea. Development and sexual identity are female.

Testes left in place produce testosterone, which is converted to estradiol. Whereas this estradiol allows for spontaneous breast development, the testes are generally removed at the time of diagnosis because of the increased risk for gonadoblastoma. Girls who have undergone prepubertal orchiectomy should receive estrogen replacement therapy.

Interlabial Masses

Masses within the vagina in infants and young girls are generally referred to as interlabial masses. Whereas many of these lesions arise within the introitus, those arising in the urethra or bladder must be recognized to afford proper management. Many patients with masses within the vaginal area report leakage of fluid (eg, urine, pus, or transudate). A complete physical examination of the introitus is part of the evaluation for urinary incontinence.

Skene glands (paraurethral glands)

These tubular glands arise from the urethral epithelium and are the counterparts to the male prostatic glands. In females, Skene glands may end up in the urethral meatus and hymen. Cysts (tense, yellow, thin-walled) arising partially within the urethral meatus but mostly external to it may resemble a bulging hymen associated with hydrometrocolpos or a prolapsing ureterocele but are usually separate from the urethral opening. [23, 24]

Bartholin glands

The major vestibular glands of Bartholin arise from the urogenital sinus and open into the vestibule on either side of the hymen. The main glands lie against the ischiopubic ramus deep to the bulbospongiosus muscle and cavernous tissue. Blockage of the main ducts of the Bartholin glands may lead to cystic dilatation in females of any age, but they rarely become infected before puberty.

Prolapsed ureterocele

A ureterocele is a dilated distal ureter within the detrusor muscle that may extend beyond the bladder neck (ectopic ureterocele). These ureters are often associated with an upper-pole renal moiety of a duplicated collecting system. An interlabial mass may be identified if the ectopic ureterocele extends through the urethral meatus. Treatment is directed at ureterocele excision, ureteral reimplantation, and possible reconstruction of the bladder base and bladder neck, where the muscle layer may not have developed normally.

Hydrocolpos and hydrometrocolpos

Circulating maternal estrogen in the female newborn may result in an increase in the production of cervical mucus. Hydrocolpos and hydrometrocolpos results when mucus collects in the vaginal vault and uterus, respectively. In these instances, the vaginal orifice may be blocked secondary to an imperforate hymen, a urogenital sinus, an atretic rectocloacal canal, or vaginal/uterine atresia.

Hydrometrocolpos, by virtue of its abdominal extension, may compress the urethra, rectum, and ureters. Treatment of hydrocolpos and hydrometrocolpos due to a normally located imperforate hymen may involve simple perforation of the hymen in the newborn nursery. If the hymen appears thickened, incision under general anesthesia may be required. Higher obstruction involves a more formal approach to treat the associated urogenital abnormalities of vaginal atresia, urogenital sinus, or a rectocloacal canal.

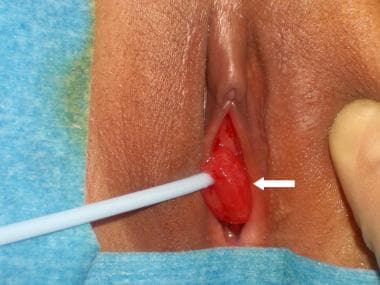

Urethral prolapse

Eversion of the distal urethral mucosa through the urethral meatus results in a circumferential interlabial lesion (see the image below). These lesions may be painful, may bleed, or may weep serosanguineous fluid, prompting medical attention, but they do not lead to urinary incontinence. Examination reveals edematous or necrotic tissue exiting the urethral meatus. Visualization of the urethral meatus in the center of this tissue helps to distinguish this lesion from neoplasms of the vagina or bladder.

A prolapsed urethra associated with mild edema without necrosis or significant pain may be treated conservatively with sitz baths and estrogen cream over a 2- to 3-week period. More symptomatic lesions should be excised. [25]

Rhabdomyosarcoma of the vagina

Patients with rhabdomyosarcoma of the vagina and bladder may present with a grapelike interlabial lesion associated with vaginal bleeding. Because of the propensity to spread, a complete endoscopic and radiographic evaluation is indicated to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out local extension and distant lesions. Primary chemotherapy has resulted in better bladder salvage and can cure metastatic disease. Surgical excision with or without radiation therapy is reserved for postchemotherapy biopsy-proven residual masses. [26]

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence in children can significantly affect self-esteem and social adjustment. In one study, children rated wetting themselves at school as the third most catastrophic event behind loss of a parent and going blind. Therefore, a patient but aggressive approach is certainly indicated in the management of these children. A positive and supportive attitude is indicated; the vast majority of children achieve continence over time.

All children who present with urinary incontinence should undergo a careful history, physical examination, and urinalysis. [27] The history should focus on determining the timing, onset, and duration of symptoms. New stressors at home or school can cause changes in voiding patterns. Symptoms such as urgency, frequency, diurnal incontinence, and holding maneuvers (ie, “the potty dance”) are typical of children with dysfunctional voiding.

Bowel and bladder function are intimately related. Many of these children also have constipation; the combination of urinary and bowel symptoms is referred to as dysfunctional elimination syndrome. [28, 29]

The physical examination should focus on palpation of the abdomen (for distended bladder, hydronephrosis, or stool) and a thorough genital examination to evaluate for labial adhesions, vaginal discharge, interlabial masses, or an ectopic ureter. Evaluation of the back and anus is also indicated to confirm the integrity of spinal cord function (sphincter tone, anal wink) and to look for abnormal sacral dimples or hairy patches, which may indicate spina bifida. A neurologic examination should also be performed.

Finally, urinalysis is essential in the evaluation to assess for infection, renal concentrating defects (early morning specific gravity < 1.022), hematuria, proteinuria, and glucosuria, which may suggest diabetes.

In many cases, treatment of constipation (ie, Miralax therapy and/or fiber supplements) alone alleviates coexisting urinary symptoms. Otherwise, the management of dysfunctional voiding begins with management of constipation and timed voiding every 3 hours, which is strictly enforced. Double voiding and anticholinergic therapy (ie, oxybutynin) are often used to treat refractory cases.

The most common cause of severe refractory urinary incontinence in children is related to a neurologic deficit. The leading causes of neurogenic incontinence include myelomeningocele (spina bifida), sacral agenesis, and vertebral or spinal cord lesions. In these conditions, changes within the spinal cord may occur over time and mandate careful evaluation and close follow-up. In the vast majority of cases, obvious physical findings suggest a neurogenic cause for incontinence. In the absence of such findings, a radiographic workup is conducted only in the setting of refractory symptoms.

Incontinence may be broadly divided between that which requires surgical intervention and that which requires medical or behavioral therapies. In general, incontinence that is related to primary nocturnal enuresis (PNE) or infrequent voiding tends to resolve with time and does not require surgery. The following sections address the clinical presentation, evaluation, and treatment of lower urinary tract abnormalities that are associated with urinary incontinence in girls.

Causes of Urinary Incontinence in Girls

Functional causes of urinary incontinence

Functional causes of urinary incontinence include PNE, dysfunctional voiding, and pseudoincontinence (eg, vaginal voiding).

Primary nocturnal enuresis

PNE is defined as persistent night wetting in individuals older than 5 years. It occurs in approximately 20% of 5-year-old children, and the incidence decreases with age. Whereas PNE is more common in boys, daytime wetting, urinary urgency, and frequency are more common in girls. The diagnosis and treatment of nocturnal enuresis is multifactorial, depending on the pathophysiology and psychologic analysis of the patient.

Treatments using desmopressin (1-deamino-8-arginine-vasopressin [DDAVP]), imipramine, bedwetting alarms, or combinations of these therapies are often successful and are usually initiated at age 6 years. [30] Daytime symptoms, such as enuresis, urgency, and frequency, require careful evaluation and may be treated with anticholinergic medications. [31, 32]

Dysfunctional voiding

Children with dysfunctional voiding have difficulty relaxing their pelvic floor musculature. This musculature comprises the external urethral sphincter. Also, the rectum traverses through the pelvic floor musculature. As a result, daytime and nighttime wetting, urinary frequency or infrequency, urgency, UTI, and constipation or encopresis are common.

Having patients and their families keep an elimination diary to ascertain the child's specific toilet habits is useful. For example, many parents are not aware that their child has constipation unless specifically queried as to the frequency and caliber of the stool. Simple treatment of constipation with stool softeners (eg, mineral oil, Kondremul) or laxatives (eg, Miralax, Dulcolax) permits better overall toilet behavior. Voiding dysfunction may be treated by behavior modification or pharmacologic agents and does not require surgical intervention. [33]

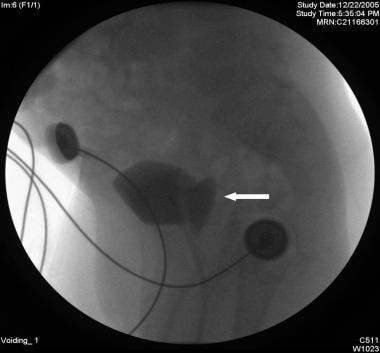

Vaginal voiding

Vaginal voiding is often confused with true urinary incontinence (see the image below). Micturition into the vagina results in leakage when the child stands upright, which allows efflux of urine from the vaginal vault. Simple maneuvers that better direct the urinary stream, such as separating the legs further apart during voiding and waiting a few minutes after micturition to allow efflux into the toilet, usually solve the problem.

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) showing vaginal reflux (arrow) during the voiding phase of the study.

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) showing vaginal reflux (arrow) during the voiding phase of the study.

Very rarely is the urethral lumen located inside the vagina (female hypospadias). This may promote vaginal voiding and may require surgical repositioning of the urethra.

Congenital abnormalities that cause incontinence

Congenital anomalies may cause incontinence by interfering with the function of the sphincter mechanisms, by interfering with the storage function of the bladder, or by anatomically bypassing normal sphincter mechanisms. Imaging studies are essential to define the anatomic abnormalities causing the incontinence.

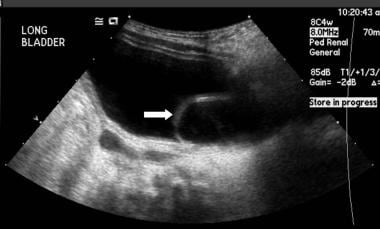

Renal and bladder US (RBUS) and voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) are usually the first studies obtained. RBUS is excellent in assessing for duplication anomalies and in revealing hydronephrosis. Hydronephrosis may be caused by VUR, an ectopic ureter, or a ureterocele, which is often visible on bladder images (see the image below). VCUG is the most commonly used method to assess for VUR. The plain abdominal scout radiograph of the VCUG can be used to assess for bony abnormalities and for fecal impaction.

Renal/bladder ultrasound showing cystic structure in the expected area of the left ureteral orifice consistent with a ureterocele.

Renal/bladder ultrasound showing cystic structure in the expected area of the left ureteral orifice consistent with a ureterocele.

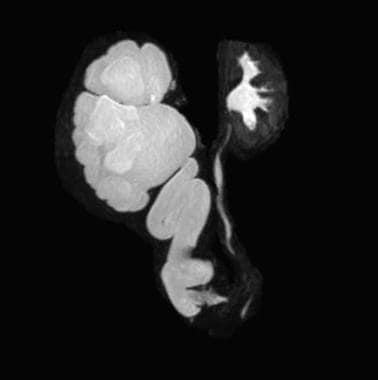

If significant hydronephrosis is present or if the kidneys appear echogenic or scarred, renal scintigraphy (renal scan) can be obtained to determine differential function. If the anatomy or function is still unclear, gadolinium-enhanced MRU can be useful [34] (see the image below). Urodynamic studies are often useful in detecting sphincteric, storage, and urinary flow abnormalities and are essential in all patients with neurogenic incontinence.

Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) showing severe left hydroureteronephrosis resulting from an ectopically inserted ureter.

Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) showing severe left hydroureteronephrosis resulting from an ectopically inserted ureter.

The treatment goals of congenital abnormalities of the female GU tract include restoration of physical appearance and function, preservation of renal function, and achievement of manageable urine storage and continence.

Myelomeningocele

In the pediatric population, myelomeningocele is a common cause of neurogenic bladder, leading to problems with urinary storage, sphincteric function, and elimination. In the United States, the prevalence is approximately 1 per 1000 births.

CIC in conjunction with anticholinergic medications has led to a dramatic improvement in the management of patients with myelomeningocele. [35] The use of CIC has been shown to promote continence, to preserve renal function, and to decrease the incidence of symptomatic pyelonephritis. In 1981, McGuire et al determined that a leak point pressure (LPP) greater than 40 cm H2O predicted renal deterioration over time. CIC serves to keep bladder pressure low, avoiding high LPP. [36]

Abnormal sphincter

Anatomic abnormalities may impede normal development of the bladder neck. Incompetence of the bladder neck may result in primary urinary incontinence and is observed in conditions such as female epispadias, urogenital sinus, bilateral ureteral ectopia, and ectopic ureteroceles. Conservative measures to improve sphincteric function are limited, and a surgical approach is needed. The surgical options focus on creating an increase in bladder outlet resistance (eg, with the bladder neck sling procedure [37] ) or on creating a new sphincter mechanism.

Reconstruction of Urinary Tract

Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in pediatric patients undergoing urologic procedures remain to be defined. An Italian consensus study concluded that surgical antibiotic prophylaxis was not needed for clean procedures (eg, circumcision, chordee repair, inguinal hernia repair, orchidopexy, urethromeatoplasty, and scrotal procedures) in these patients but should be employed for clean-contaminated procedures (eg, nephrectomy, cystectomy, endoscopy, vaginal procedures, hypospadias repair, and any procedure involving an opening into the GU tract). [38]

Lower urinary tract reconstruction

Since 1950, bowel segments have been used to entirely replace a diseased or dysfunctional bladder. The current success in reconstruction of the lower urinary tract reflects the improved understanding of the physiologic principles involved in bladder and urethral function. [39, 40]

Spontaneous voiding can occasionally be achieved with an abnormal lower urinary tract, provided the pressure gradient between the bladder and distal urethra are low. Therefore, even in cases in which the bladder is replaced in part (intestinal cystoplasty) or entirely (neobladder), patients may still be able to empty their bladders satisfactorily. Many patients require bladder-neck reconstruction to achieve continence, and most patients require CIC.

Continent reconstruction of the lower urinary tract is often desired in the setting of congenital or acquired anomalies of the outlet and the bladder. The early work of Hendren, Mitchell, Mitrofanoff, and others led to surgical approaches that produce better reservoir function and a continent outlet. [41, 42] Continent urinary diversion encompasses the following three interrelated but independently functioning components [43] :

-

Channel by which urine is conducted to the skin

-

Reservoir or pouch

-

Mechanism by which continence is achieved

A number of tissues are available to the reconstructive surgeon.

The flap-valve principle for continence dictates that a portion of the continence channel must be fixed on the inner wall of the reservoir. This is the same principle by which ureteral tunneling in the bladder muscle prevents reflux during voiding. In general, a 5:1 length-to-diameter ratio is required for the continence structure, regardless of whether the structure is ureter, ileum, or appendix.

The Mitrofanoff principle of continent reconstruction describes a supple catheterizable structure (eg, ureter or appendix) implanted into the inner wall of the reservoir to create a flap-valve continence mechanism. The most popular form of flap-valve construction for urinary continence is the use of appendix implanted into the bladder or reservoir (appendicovesicostomy). The small stoma may be concealed within the umbilicus.

Assurance of complete bladder emptying is essential because this type of continence channel is very effective in its ability to withstand very high intraluminal pressure. In the noncompliant patient, pouch rupture or upper tract injury may result from failure to empty the reservoir regularly.

Urinary tract reconstruction and pregnancy

Potential future pregnancy must be considered in the reconstruction of the GU tract. Pregnancy may be complicated and requires care by the obstetrician and urologist. Renal obstruction and incontinence may result as the uterus enlarges. Neobladder reconstruction yields a good outcome, but chronic bacteriuria is common and occasionally necessitates the use of an indwelling catheter in the third trimester. Likewise, when suprapubic catheterizable continent stomas have been constructed, indwelling catheterization through the stoma during the third trimester may be needed to avoid serious UTIs. [44]

Successful pregnancies and deliveries have been reported after continent and loop urinary diversions. [45] Obstetric indications should guide the mode of delivery, though abdominal delivery has been successful in most cases. Alternatively, if the bladder neck has been reconstructed, performing a cesarean delivery to avoid damage to the bladder neck reconstruction is usually advisable. The urologist should be available to the obstetric team for consultation if caesarean delivery is deemed necessary, especially if a bladder augmentation with bowel has been performed, in order to avoid injury to the vascular pedicle of the bowel segment. [46]

-

Female bladder exstrophy.

-

Female epispadias.

-

Cloacal exstrophy.

-

46,XX difference (disorder) of sex development (female pseudohermaphroditism). Note clitoromegaly and small introitus.

-

Urethral prolapse (arrow).

-

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) showing vaginal reflux (arrow) during the voiding phase of the study.

-

Renal/bladder ultrasound showing cystic structure in the expected area of the left ureteral orifice consistent with a ureterocele.

-

Magnetic resonance urography (MRU) showing severe left hydroureteronephrosis resulting from an ectopically inserted ureter.