Background

Neonatal intestinal obstruction comprises many conditions, as obstruction may occur at any point in the gastrointestinal tract. [1, 2, 3] Even when restricting one's focus to a single location, several variations of obstruction are possible. The general principles involved in managing intestinal obstruction are the same regardless of the patient population, from the newborn to the geriatric.

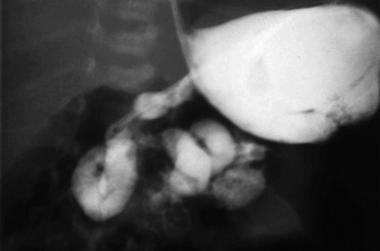

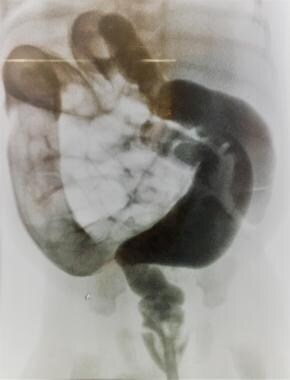

The following image depicts malrotation/volvulus.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation/volvulus. Note the spiral twist and the partial obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation/volvulus. Note the spiral twist and the partial obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction occurs in approximately 1 in 2000 births [4] ; hence, it is a frequent reason for pediatric surgical consultation. [5] Neonatal intestinal obstruction is suggested by the following features [1] :

-

Maternal polyhydramnios

-

Feeding intolerance

-

Bilious emesis

-

Abdominal distention

-

Delayed passage of meconium

-

Absent transitional stools

Classic clinical signs of neonatal intestinal obstruction are vomiting, abdominal distention, and failure to pass meconium. [5] However, the infant's clinical presentation is dependent on the anatomic level of the obstruction, as follows:

-

Foregut obstruction: Infants with foregut obstructions have difficulty swallowing, or they regurgitate or vomit gastric contents. Their abdominal examination may show localized distention, as in the left upper quadrant bulge that is typical of pyloric stenosis. Prolonged vomiting produces a characteristic electrolyte disturbance (hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis).

-

High (jejunal) obstruction: Babies with high (jejunal) obstructions vomit bilious succus entericus. Their abdominal evaluation reveals a scaphoid abdomen; however, a mass (distended bowel) may be palpable. Nasogastric output is generally voluminous, and characteristic electrolyte abnormalities (hyperkalemic metabolic acidosis) are present.

-

Distal small bowel or colonic obstruction: Babies with obstruction at these anatomic levels present with feeding intolerance and abdominal distention. If the diagnosis is delayed, feculent emesis may occur. Abdominal palpation may reveal a mass (intestinal duplication or intussusception). Plain radiographs show multiple dilated loops of bowel.

It is important to exercise clinical acumen. Conduct the following:

-

Obtain an accurate history.

-

Perform a careful, thorough physical examination.

-

Obtain radiographs that corroborate or refute the "working diagnosis."

Once the correct diagnosis is ascertained, the surgeon can decide upon an appropriate intervention. Fortunately, the outlook for babies with intestinal obstruction is generally excellent. [6, 7]

Intestinal obstruction in a patient with peritonitis constitutes a surgical emergency; the presence of pain generally denotes ischemia. A loop of bowel may be twisted, creating a "closed loop" obstruction (see the image below). Because both limbs (loops) (afferent and efferent) are obstructed, there is no outlet and the bowel becomes massively distended. If the intraluminal pressure exceeds the blood pressure, perfusion ceases and the bowel dies. In "strangulation" obstruction, the mesentery is kinked and blood flow is impaired, causing ischemia and, ultimately, gangrene.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Volvulus of a loop of intestine. The intestine is obstructed at both ends, creating a "closed loop."

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Volvulus of a loop of intestine. The intestine is obstructed at both ends, creating a "closed loop."

A patient with an incomplete or partial small bowel obstruction (SBO) may be treated expectantly; however, if the obstruction is complete (distended small bowel and collapsed colon), and the patient complains of abdominal pain, intestinal viability is threatened. Hence the adage, "Never let the sun set on a patient with intestinal obstruction!"

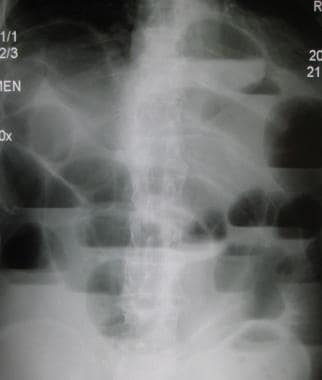

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Upright radiograph in a patient with complete intestinal obstruction. Note the air-fluid levels and absence of air in the colon.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Upright radiograph in a patient with complete intestinal obstruction. Note the air-fluid levels and absence of air in the colon.

Anatomy

Embryology

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract arises from the yolk sac. At 3-4 weeks' GA (gestational age), it becomes a distinct entity.

The vitellin or omphalomesenteric duct connects the developing midgut to the yolk sac; it may persist as a Meckel diverticulum (see the image below). The alimentary tube is divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut. Although there is some overlap, each division has a separate "named" blood supply.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Omphalomesenteric duct (Meckel diverticulum) attached to the umbilicus.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Omphalomesenteric duct (Meckel diverticulum) attached to the umbilicus.

Foregut

The esophagus, stomach, and duodenum are vascularized by multiple sources, including the thyrocervical trunk, intercostal vessels, and celiac axis.

Midgut

The jejunum, ileum, and ascending and proximal transverse colon are vascularized by the superior mesenteric vascular pedicle.

Hindgut

The distal transverse colon and the descending and sigmoid colon are supplied by the inferior mesenteric vessels.

The rectum is supplied by the internal iliac vessels.

Sites and causes of obstruction

Obstruction may occur anywhere in the GI tract:

Esophagus

Esophageal atresia (see the image below) is usually associated with tracheoesophageal fistula. Esophageal webs may also cause obstruction

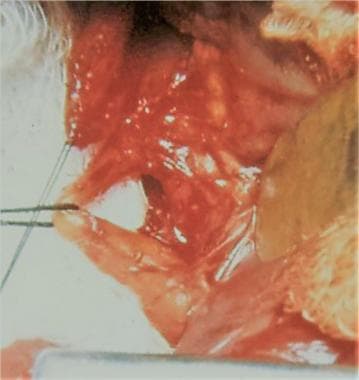

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph showing proximal esophageal atresia and distal tracheoesophageal fistula.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph showing proximal esophageal atresia and distal tracheoesophageal fistula.

Stomach

An antral atresia or mucosal web may occur, but it is exceedingly rare (see the next image). Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is an acquired disorder and termed "congenital" to distinguish it from cicatricial stenosis caused by peptic ulcer disease (see the second image below). Gastric volvulus may also cause obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. The pylorus is thickened and elongated.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. The pylorus is thickened and elongated.

Duodenum

Duodenal atresia or stenosis is caused by a developmental error, incomplete canalization, by coalescence of vacuoles within the solid tubular anlage. [8] Duodenal obstruction is frequently associated with Down syndrome. It may also result from malrotation and/or volvulus (see the image below). When malrotation occurs, the tissue that normally creates the duodenal C loop (around the pancreas) overlies and compresses the duodenum; this tissue forms "Ladd bands," named in honor of the surgeon who devised the operation used to prevent midgut volvulus.

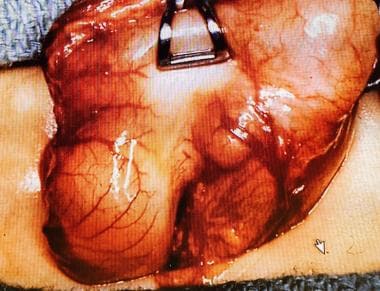

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of midgut volvulus. Note the transverse orientation of the colon (look for the appendix).

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of midgut volvulus. Note the transverse orientation of the colon (look for the appendix).

Small intestine

Jejunal or ileal atresia may have continuity in the bowel and mesentery, or there may be a gap of varying distance (see the first two images below). If a thromboembolic event destroyed the proximal mesentery, blood from the ileocecal vessels may flow retrograde into the proximal intestine; as the bowel winds around these vessels, it resembles an "apple peel” or "Christmas tree" (see the third image below). Rarely, there may be multiple obstructions, giving the bowel a "string of sausages" appearance (see the fourth image below).

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Jejunal atresia. Note the sharp transition between the proximal dilated jejunum and the distal unused intestine at the point of the atresia.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Jejunal atresia. Note the sharp transition between the proximal dilated jejunum and the distal unused intestine at the point of the atresia.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of jejunoileal atresia. The bowel is obstructed but in continuity.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of jejunoileal atresia. The bowel is obstructed but in continuity.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. When the proximal mesentery is destroyed in jejunal atresia, the ileum may derive its blood supply from the ileocolic vessels and wraps around these vessels, creating the appearance of a "Christmas tree" or "apple peel."

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. When the proximal mesentery is destroyed in jejunal atresia, the ileum may derive its blood supply from the ileocolic vessels and wraps around these vessels, creating the appearance of a "Christmas tree" or "apple peel."

Meconium ileus (see the next image) or an incarcerated inguinal hernia may also cause small intestinal obstruction.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Meconium ileus. Intraluminal intestinal obstruction from thick, tenacious meconium.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Meconium ileus. Intraluminal intestinal obstruction from thick, tenacious meconium.

Omphalomesenteric (or Meckel) bands may entrap a loop of small intestine or cause it to flip, creating a “closed-loop” obstruction, in which there is no egress; this leads to massive dilatation and ischemia (La Place law).

In the same manner that bulky ovarian cysts cause torsion, a bulbous loop of intestine or an enteric duplication may precipitate torsion. Prompt surgical intervention is necessary to salvage the intestine. Fortunately, these events occur infrequently.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. An enteric duplication may cause twisting (volvulus) of a loop of intestine.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. An enteric duplication may cause twisting (volvulus) of a loop of intestine.

Colon

Causes of colon obstruction include colonic atresia, meconium plug, small left colon syndrome, and Hirschsprung disease. Hirschsprung disease (aganglionic megacolon) may present during the newborn period or later. Faulty innervation (absence of ganglion cells) interrupts peristalsis, both contraction and relaxation. Agangionic bowel is unable to relax, and this nixes propulsion. (Before the etiology of Hirschsprung disease was understood, surgeons removed the dilated intestine, assuming that it was flaccid and unable to contract; however, the correct etiology was the exact opposite.)

Rectum

In rectal atresia, an obstruction is noted inside a normal-appearing anal canal.

Anus

Imperforate anus may cause obstruction. Anorectal anomalies are immediately apparent by inspection of the perineum (see the following image); however, accurate diagnosis may require radiographic studies, endoscopy, or laparoscopy. In high imperforate anus, the rectum ends as a fistula in the urinary tract in males and in the vagina in females.

Pathophysiology

Foregut anomalies

Duodenal atresia

Duodenal atresia results from defective canalization of the solid duodenal anlage, wherein vacuoles form and coalesce, creating a lumen. This process occurs during the eighth week of gestation. There are multiple presentations [8] :

-

There may be a membranous obstruction, which usually is located near the ampulla of Vater; the dilated proximal duodenum and diminutive distal duodenum are in continuity. Mucosal webs may be fenestrated, creating a partial obstruction.

-

Occasionally, the obstructing web is redundant and may protrude into the distal bowel like a “wind sock”. If the obstructing membrane is not apparent when the duodenum is opened, manipulating a tube from the stomach into the duodenum will help identify the obstruction.

-

There may be discontinuity, with a gap of varying lengths, between the dilated proximal duodenum and the hypoplastic distal duodenum. If the gap is long, repair by duodenojejunostomy may be more feasible than duodenoduodenostomy.

-

An annular pancreas marks the site of the obstruction, without actually being the cause of the obstruction. Duodenal atresia is corrected by anastomosing the proximal dilated duodenum to the distal duodenum.

Midgut anomalies

Malrotation

The peritoneum normally attaches the duodenum and the ascending colon to the retroperitoneum, creating the ligament of Treitz in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and the right lateral paracolic gutter, the "white line of Toldt." Normally the two ends of the midgut are spread wide apart, and the base of the mesentery is wide. In malrotation, however, the proximal and distal ends of the midgut, the duodenum, and the cecum, are bound together by peritoneum (Ladd bands) as well as bound to and overlie their blood supply (superior mesenteric vessels). Thus, in malrotation the base of the mesentery is narrow and may become a fulcrum about which the entire midgut may twist. This is termed, midgut vovulus, and its occurrence is potentially catastrophic because the blood supply to the entire small intestine and half of the colon may be compromised. [9] (As noted earlier, William E Ladd is the surgeon whose operative procedure is used to prevent midgut volvulus in a patient with malrotation. [10] )

Jejunoileal atresia

Jejunoileal atresia is caused by a vascular accident rather than a defect in embryogenesis. In their classic work on fetal dogs, Louw and Barnard showed that the extent of intestinal loss varied according to the timing and the extent of the disruption of the mesenteric blood supply. [11]

Atresias may be proximal or distal, single or multiple; there may be minimal or massive loss of intestinal length, depending upon the extent of the mesenteric vasculature disruption. The distal intestine may survive via retrograde blood flow from the ileocolic vessels. In these cases, the tiny (unused) intestine coils around the ileocecal vessels and looks like an "apple peel" or "Christmas Tree." Other in utero events such as gastroschisis or intussusception may also be associated with intestinal atresia. [12]

Meconium ileus

Meconium ileus is associated with cystic fibrosis, an autosomal recessive condition that diminishes membrane transport of chloride and water; this increases the viscosity of mucus and impairs transport by beating cilia, which is vital to tracheobronchial toilet. An estimated 10%-20% of newborns with cystic fibrosis present with meconium ileus, an association first described by Landsteiner in 1905. [13, 14]

Meconium plug syndrome may be considered as neonatal constipation. The infant's meconium is thick and difficult to evacuate. A water-soluble contrast enema confirms the diagnosis and, when followed by an evacuation, it is therapeutic. If the baby continues to have problems stooling, Hirschsprung disease should be considered and a rectal biopsy performed.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Contrast enema in a baby with a small left colon and meconium plug syndrome.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Contrast enema in a baby with a small left colon and meconium plug syndrome.

The following conditions may predispose to meconium plug syndrome or small left colon syndrome:

-

Maternal preeclampsia

-

Maternal ingestion of magnesium sulfate

-

Prematurity

-

Sepsis

Hirschsprung disease

Harold Hirschsprung, a Danish pediatrician, was puzzled by the death of two infants with refractory constipation. Autopsy showed dilatation and hypertrophy of the sigmoid colon and a normal-appearing rectum. In 1886, he reported this bizarre association and postulated a congenital etiology. Even after the absence of ganglion cells was identified as the determinant factor, it took time for surgeons to devise an effective operation, so convinced were they that the dilated, hypertrophied bowel was abnormal. In fact, the inability of the normal-appearing rectum to relax was the critical factor.

Peristalsis requires sequential contraction and relaxation, mediated by the neuroenteric system. During embryologic development, neural crest cells migrate along the bowel mesentry (cranial to caudal), differentiate, and populate the submucosa and muscular layers as ganglion cells. Normally, the rectum is reached by the tenth week following gestation. In Hirschsprung disease, the embryonic migration of ganglion cells is arrested proximal to the rectum—usually the sigmoid colon. The transition (± ganglion cells) is determined by the "leveling biopsy"; the most distal bowel with ganglion cells is "pulled through" the pelvis to become the "neorectum."

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The contrast enema in a baby with Hirschsprung disease; the rectum is small and the sigmoid colon is dilated.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The contrast enema in a baby with Hirschsprung disease; the rectum is small and the sigmoid colon is dilated.

Mechanisms of obstruction

The mechanism by which intestinal obstruction may be caused include intrinsic (developmental) defects or extrinsic factors (kinks, twists), or the obstruction may be intraluminal, as follows:

-

Intrinsic factors: The obstructed bowel may be in continuity, partitioned by a web (duodenal atresia), or the two ends may be entirely separate with a gaping mesentery, or there may be a functional abnormality (aganglionosis).

-

Extrinsic factors: Bands (Ladd or Meckel) may cause compression; a bulbous duplication cyst may cause volvulus; or a knuckle of bowel may become incarcerated in an inguinal (or Morgagni) hernia.

-

Intraluminal: Obstruction may be caused by inspissated meconium (meconium ileus or meconium plug syndrome).

Etiology

Faulty embryogenesis leading to the development of neonatal intestinal obstruction may result from the following:

-

Genetic factors: Duodenal atresia is associated with trisomy 21 in 30% of cases. [4]

-

Environmental exposure in utero may lead to VACTERL syndrome: V ertebral anomalies, imperforate A nus, congenital C ardiac disease, T racheoesophageal fistula, E sophageal atresia, R enal anomalies, and Limb anomalies (radius)

-

Placental thromboembolic event(s) may cause fetal mesenteric vascular accidents and damage the developing intestine (atresia, stenosis).

Genetic factors

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Mother and daughter both had pyloric stenosis. Pyloric stenosis is more common in males, but if the mother had pyloric stenosis, her offspring are more likely to be affected than if the father had it. Pyloric stenosis cases occur in clusters, indicating an environmental trigger, but there is most likely a complicated interaction of heredity and environment.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Mother and daughter both had pyloric stenosis. Pyloric stenosis is more common in males, but if the mother had pyloric stenosis, her offspring are more likely to be affected than if the father had it. Pyloric stenosis cases occur in clusters, indicating an environmental trigger, but there is most likely a complicated interaction of heredity and environment.

A single genetic abnormality may be associated with multiple anomalies.

-

Babies with trisomy 21 may have imperforate anus, congenital heart disease, duodenal atresia, or Hirschsprung disease.

-

Genetic abnormalities are rare in babies with jejunoileal atresia.

The gene for cystic fibrosis is carried by 4% of Ashkenazi Jews and 1% of Asians.

-

In 1988, the genetic mutation causing cystic fibrosis was identified on the q31.2 locus on chromosome 7.

-

Since then, over 1400 mutations have been identified in this gene, which contains 230,000 base pairs and codes for the protein cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTCR). [13]

-

Abnormalities in CFTCR disrupt the ingress and egress of sodium and chloride ions through cellular membranes. The meconium of affected babies is thick and sticky and, given the poor motility of immature intestine, may lead to intraluminal obstruction, meconium ileus. Contrast enema will show an unused microcolon.

Hirschsprung disease is associated with multiple genetic defects, a phenomenon termed oligogenic inheritance. As such, it may serve as a model for understanding other disorders of bowel motility.

-

The RET proto-oncogene, located at chromosome 10q11.21, interacts with a protein, EDNRB, which is encoded by the gene EDNRB, located on chromosome 13.

-

Mutations in RET and related signaling pathways, and modifier genes on 3p21, 9q31 and 19q12, lead to failure of migration of the enteric neural crest cells during fetal development.

-

Syndromic cases of Hirschsprung disease (associated with other defects of the autonomic nervous system) are associated with mutations in the homeobox gene PHOX2B.

-

Six other genes are associated with Hirschsprung disease, including GDNF on chromosome 5, EDN3 on chromosome 20, SOX10 on chromosome 22, ECE1 on chromosome 1, NTN on chromosome 19, and SIP1 on chromosome 2.

Epidemiology

Malrotation

The incidence of malrotation is 1 in 6000 newborns.

-

Obstructive symptoms usually occur during the first month of life (50% of cases)

-

90% of cases present during the first year of life.

-

The diagnosis, however, may be delayed until adulthood. [15]

-

One in 1000 newborns have an asymptomatic anomaly of intestinal rotation and fixation.

-

Malrotation is associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia, gastroschisis, and omphalocele.

Duodenal obstruction

Duodenal obstruction affects as many as 1 in 6,000-10,000 infants.

-

Duodenal atresia is present in 4% of infants with trisomy 21, who frequently have associated congenital heart disease.

-

Jejunoileal atresia occurs more frequently, 1 in 1,500 births.

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis occurs in 1 in 3000 live births.

-

This condition is the most common genetic disease in people of European origin.

-

It is present in 10%-20% of babies with meconium ileus. [14]

Hirschsprung disease

Hirschsprung disease affects 1 in 4,500-7,000 newborns.

-

This condition is more common in white individuals.

-

Males are affected four times as frequently as females.

-

A family history of Hirschsprung disease is present in approximately 12.5% of patients.

-

These patients typically have more extensive involvement (total colonic aganglionosis).

Imperforate anus

The incidence of imperforate anus is 3 per 10,000 births

-

There is a female predominance

-

Administration of folic acid during pregnancy reduces the incidence to 1 in 10,000 births.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Baby with a high imperforate anus; note the indistinct perineum ("rocker bottom"). Compare this photograph with the low imperforate anus photograph in the section "Surgical Relief of Obstruction," in which "pearls" of meconium along the scrotal raphe can be seen.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Baby with a high imperforate anus; note the indistinct perineum ("rocker bottom"). Compare this photograph with the low imperforate anus photograph in the section "Surgical Relief of Obstruction," in which "pearls" of meconium along the scrotal raphe can be seen.

Prognosis

The prognosis for duodenal and jejunoileal atresia is similar: relatively normal bowel function can be expected, except in cases of short-gut syndrome.

The long-term outlook for a patient with meconium ileus is determined by the severity of the cystic fibrosis and the effectiveness of its management.

Most patients with meconium plug syndrome have an excellent outcome after relief of the obstruction, and no further intervention is required.

Bowel dysmotility issues (refractory constipation and episodes of enterocolitis) such as the following may continue to plague patients with Hirschsprung disease, even after removing the aganglionic colon and rectum:

-

Disordered motility in the proximal colon (elucidated by manometry)

-

Internal anal sphincter achalasia (treated with Botox or sphincterotomy)

-

Functional megacolon with stool retention (usually responds to bowel management program) [16]

The outlook in patients with anorectal anomalies is complex and is influenced by factors other than the operative procedure.

-

If the sacrum is normal, usually the pelvic musculature and its innervation are intact.

-

Colonic motility, in most patients with anorectal abnormalities, is sluggish, and the patients are constipated.

-

A minority of patients, however, have hypermotility; these patients have diarrhea.

-

Continence is far easier to achieve in patients with anorectal who have constipation.

-

Bowel management programs, enemas, cathartics, and antispasmotics are all utilized, as indicated.

Morbidity/mortality

The morbidity and mortality from malrotation/volvulus (see the images below) are related to the loss of intestine. The mortality may be as high as 65%, if more than 75% of the small bowel is necrotic. Survivors may develop short-gut syndrome, with the attendant complications of malabsorption and malnutrition. [17]

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation with volvulus of the proximal small intestine coiled around the superior mesenteric vessels.

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation with volvulus of the proximal small intestine coiled around the superior mesenteric vessels.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation/volvulus. Note the spiral twist and the partial obstruction.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation with volvulus of the proximal small intestine coiled around the superior mesenteric vessels.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Partial duodenal obstruction: duodenal stenosis or malrotation/volvulus? Note the "double bubble" sign and narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum; however, the duodenum does cross the midline and it is not twisted.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Jejunal atresia. Note the sharp transition between the proximal dilated jejunum and the distal unused intestine at the point of the atresia.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Jejunal atresia. Ischemic compromise of the proximal segment is noted.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Meconium plug syndrome. Contrast enema shows a dilated colon proximal to the meconium plug. If the enema elicits an evacuation, the obstruction may be relieved.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Baby with a high imperforate anus; note the indistinct perineum ("rocker bottom"). Compare this photograph with the low imperforate anus photograph in the section "Surgical Relief of Obstruction," in which "pearls" of meconium along the scrotal raphe can be seen.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. This diagram is a sample algorithm for the diagnosis of neonatal intestinal obstruction.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. The pylorus is thickened and elongated.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of jejunal atresia with a mesenteric gap and discontinuous bowel segments.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Meconium ileus. Intraluminal intestinal obstruction from thick, tenacious meconium.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Colonic atresia. The hugely dilated colon will never function satisfactorily; therefore, it is resected, leaving a cuff of cecum to preserve the ileocecal valve.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of midgut volvulus. Note the transverse orientation of the colon (look for the appendix).

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Omphalomesenteric duct (Meckel diverticulum) attached to the umbilicus.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Colon pull-through for Hirschsprung disease.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Midgut volvulus. Necrosis of the midgut is the the most feared complication of malrotation/volvulus.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Malrotation volvulus. Note the partial duodenal obstruction. The distal duodenum does not cross the midline (over the vertebral column) and the "curly Q" twist.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Gastrografin enema. Note the tiny, unused colon and the dilated (by swallowed air) proximal, obstructed intestine.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Midgut volvulus. The bowel is eviscerated and the entire midgut is twisted counterclockwise, effecting reduction of the volvulus.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The midgut volvulus is reduced.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Photograph of neonatal intestinal perforation. Note the aneurysmal dilatation of the (perforated) intestine proximal to the obstructed (by inspissated stool) distal ileum.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The contrast enema in a baby with Hirschsprung disease; the rectum is small and the sigmoid colon is dilated.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph showing dilatation of the sigmoid colon and a small caliber rectum.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. When the proximal mesentery is destroyed in jejunal atresia, the ileum may derive its blood supply from the ileocolic vessels and wraps around these vessels, creating the appearance of a "Christmas tree" or "apple peel."

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph showing proximal esophageal atresia and distal tracheoesophageal fistula.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Contrast enema in a baby with a small left colon and meconium plug syndrome.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Upright radiograph in a patient with complete intestinal obstruction. Note the air-fluid levels and absence of air in the colon.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Jejunal obstruction caused by a mucosal web.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Multiple atresias have a"string of sausages" appearance.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. In babies with meconium ileus, the contrast enema shows an unused microcolon.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of jejunoileal atresia. The bowel is obstructed but in continuity.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of meconium ileus. The dilated, meconium-laden loop of intestine may be resected and an anastomosis performed.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Pull-through procedure for Hirschsprung disease. Note the biopsy site in the dilated bowel.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The contrast enema shows an unused microcolon in babies with meconium ileus.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Pyloromyotomy: carefully cutting and spreading apart the hypertrophied muscle layer without penetrating the mucosa.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Mother and daughter both had pyloric stenosis. Pyloric stenosis is more common in males, but if the mother had pyloric stenosis, her offspring are more likely to be affected than if the father had it. Pyloric stenosis cases occur in clusters, indicating an environmental trigger, but there is most likely a complicated interaction of heredity and environment.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. An enteric duplication may cause twisting (volvulus) of a loop of intestine.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Volvulus of a loop of intestine. The intestine is obstructed at both ends, creating a "closed loop."

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Initial radiograph during hydrostatic reduction of intussusception.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Radiograph when hydrostatic reduction is almost complete.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of intussusception.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. A baby with esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula, who has right upper lobe atelectasis and pneumonia. Note the abdominal distention prior to gastrostomy tube placement, and resolution of the distention and atelectasis after placement of the gastrostomy tube.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of midgut volvulus. Note the transverse orientation of the colon (look for the appendix).

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Baby with an incarcerated inguinal hernia causing intestinal obstruction. The viability of the testicle is also at risk.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of midgut volvulus, after its reduction by rotating the entire midgut in a counter-clockwise direction. Next, adhesions between the duodenum and the colon will be divided, exposing the superior mesenteric vessels.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Operative photograph of malrotation/volvulus diagnosed too late to save the midgut, which is gangrenous.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. A stricture of the small intestine, following necrotizing enterocolitis, causing intestinal obstruction.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. In a baby with jejunal atresia and extensive loss of the distal small bowel, the bulbous, dilated proximal jejunum may be narrowed and lengthened utilizing the STEP (serial transverse enteroplasty) procedure.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Anastomosis between the dilated proximal duodenum (left) and the smaller caliber distal duodenum.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Baby with a low imperforate anus. Note the "pearls" of meconium along the scrotal raphe. Low imperforate anus is amenable to repair during the neonatal period.

-

Intestinal obstruction in the newborn. The obstructed proximal jejunum is dilated, bulbous; and its motility (peristalsis) is poor. If the baby has an adequate length of distal intestine, this segment is resected; however, if there is limited distal intestine, the STEP (serial transverse enteroplasty) procedure may convert this short dilated segment to a longer, narrower segment.