Practice Essentials

Ethanol is the most common psychoactive drug used by children and adolescents in the United States. [1] Worldwide, it is one of the most commonly abused drugs, and its use in young people remains a concern because of its negative effect on brain development and increased risk of alcohol use disorders. [2]

Assessment of pediatric ethanol toxicity can be complicated by several factors. These include reluctance to admit ingestion, underestimation of the amount ingested, ingestion of other toxins (eg, methanol in perfume or cologne), and related trauma. (See Presentation.) The mainstay of treatment is supportive care. Hypoglycemia and respiratory depression are the two most immediate life-threatening complications that result from ethanol intoxication in children. (See Treatment.)

Pathophysiology

Ethanol is a 2-carbon–chain alcohol; the chemical formula is CH2 CH3 OH. Ethanol has a volume of distribution (0.6 L/kg) and is readily distributed throughout the body. The primary route of absorption is oral, although it can be absorbed by inhalation and even percutaneously.

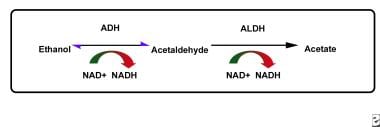

The pathway of ethanol metabolism. Disulfiram reduces the rate of oxidation of acetaldehyde by competing with the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) for binding sites on aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).

The pathway of ethanol metabolism. Disulfiram reduces the rate of oxidation of acetaldehyde by competing with the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) for binding sites on aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).

Ethanol exerts its actions through several mechanisms. For instance, it binds directly to the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor in the CNS and causes sedative effects similar to those of benzodiazepines, which bind to the same GABA receptor. Furthermore, ethanol is also an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate antagonist in the CNS. Ethanol also has direct effects on cardiac muscle, thyroid tissue, and hepatic tissue. However, the exact molecular targets of ethanol and the mechanism of action are still the subjects of ongoing research. [3, 4]

Ethanol is rapidly absorbed, and peak serum concentrations typically occur 30-60 minutes after ingestion. Its absorption into the body starts in the oral mucosa and continues in the stomach and intestine. Both high and low concentrations of ethanol are slowly absorbed; the co-ingestion of food also slows absorption.

In young children, ethanol causes hypoglycemia and hypoglycemic seizures; these complications are not as common in older patients. Hypoglycemia occurs secondary to ethanol's inhibition of gluconeogenesis and secondary to the relatively smaller glycogen stores in the livers of young children. In toddlers who have not eaten for several hours, even small quantities of ethanol can cause hypoglycemia.

Ethanol is primarily metabolized in the liver. Approximately 90% of an ethanol load is broken down in the liver; the remainder is eliminated by the kidneys and lungs. In children, ethanol is cleared by the liver at the rate of approximately 30 mg/dL/h, which is more rapid than the clearance rate in adults.

In the liver, ethanol is broken down into acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). It is then further broken down to acetic acid by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetic acid is fed into the Krebs cycle and is ultimately broken down into carbon dioxide and water. Also, a gastric isozyme of ADH breaks down a significant amount of ethanol before it can be absorbed; sex differences in ADH may, in part, account for differences between men and women in ethanol effects per given quantity consumed.

Etiology

Pediatric ethanol intoxication occurs in patterns that vary with the patient's age. Contributing factors may include poor parenting habits or inadequate supervision.

In infants and children, ethanol intoxication often has an unintentional cause. Infants usually ingest alcohol as a result of their caregivers giving them over-the-counter cold medications that contain significant amounts of ethanol. Also, parents may be misinformed about how to treat an illness. In some cultures, caregivers commonly give infants fluids that contain alcohol to treat colic, or they may even put whiskey in an infant's mouth to soothe the discomfort of teething.

In addition, infants and toddlers may be given ethanol orally or percutaneously. Usually, their caregivers do this to treat the child's cold symptoms. The parents may also give the child alcohol baths to treat a fever. This is also common with isopropanol, but baths with isopropanol may have different effects

Young children usually develop ethanol intoxication by drinking ethanol. In children, the primary sources of ingested alcohol are beverages, often in the form of a discarded drink left within the child's reach during or after parties, especially during the Christmas holiday. Other sources of alcohol include colognes or perfumes, mouthwashes, cold medicines or other medications, aftershave lotions, and cleaning fluids and other household fluids.

Adolescents may ingest alcohol as a response to peer pressure or a stressful home environment, as a way to assert their autonomy, as an escape from their daily life, or as an imitation of the habits of an adult caregivers. Older children and adolescents frequently become intoxicated by knowingly drinking alcoholic beverages with a peer group or, less frequently, as part of a suicide attempt.

Epidemiology

Ethanol use and intoxication in adolescents is widespread in the United States. In 2022, 6.8% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years were current alcohol users and 0.2% were heavy alcohol users. About 834,000 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years were past month binge drinkers, which corresponds to 3.2% of adolescents. An estimated 753,000 adolescents had a past year alcohol use disorder, or 2.9% of adolescents. [5]

In the 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 15% of high school students admitted to drinking alcohol before age 13 years and 22.7% were currently drinking alcohol. The survey also found that 4.6% of high school students who drove a car in the last 30 days reported driving after drinking alcohol, and 14.1% reported riding with a driver who had been drinking. [6]

In 2022, 7964 single exposures to ethanol in beverages, with 356 major outcomes and 56 deaths, were reported to US Poison Control Centers. Most single exposures to ethanol beverages involved adults, but 2764 of the cases involved children under the age of 6 years, and 896 involved teenagers. Ethanol-containing mouthwashes accounted for 3918 single exposures, with 26 major outcomes and no deaths. The majority (55%) were adults; children under 6 years old accounted for 659 (17%). Children younger than 6 years old represent the majority of all other ethanol exposures as follows: [7]

-

Hand sanitizers: 13,976 of 22,471 exposures (62%)

-

Non-beverage/non-rubbing alcohol: 739 of 1346 exposures (54%)

-

Ethanol-containing cleaners: 163 of 241 exposures (68%)

-

Rubbing alcohol: 80 of 153 exposures (52%)

Cases of poisoning from ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitizer have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, nearly 25,000 cases of ingested hand sanitizer were reported in the United States in children under 12. [8] In Great Britain, alcohol-based hand sanitizer poisonings reported to the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) jumped from 155 between January 1 and September 16, 2019, to 398 between January 1 and September 14, 2020. [9]

Ethanol use in countries other than the United States is common; however, literature about the incidence of ethanol intoxication in pediatric populations in other countries is scant. Data supporting a racial predilection in pediatric populations are limited. Studies of adult patients suggest a lower tolerance in patients of Asian descent. This is most likely due to differences in expression or enzyme activity of ADH.

Studies in adults have reported that gastric ADH breaks down a significant amount of ethanol before it can be absorbed, which may, in part, account for differences in tolerance between men and women. Interestingly, one study found that in high school students, more drinking without binges was reported by girls than by boys, but binge-drinking rates were similar. [10]

Prognosis

The prognosis for pediatric patients with ethanol toxicity is excellent, provided the patient can avoid both the long-term use of alcohol and the short-term complications of alcohol use. Short-term complications include the following:

-

Risky behaviors (eg, increased likelihood of illicit drug use)

-

Increased risk of trauma

-

Legal consequences

Long-term complications of chronic ethanol use in children are not well described in the medical literature. Complications usually develop over several years. Because most pediatric patients do not start using ethanol until later in their adolescence, they do not present with long-term complications such as liver dysfunction (eg, cirrhosis) and cardiac problems until after they become adults.

Research has confirmed that intense neurologic development occurs both in utero and during adolescence. Heavy drinking in adolescents has been associated with deficits in visuospatial function. Heavy drinking in adolescents may also lead to chronic neurologic damage of a similar mechanism to that seen in fetal alcohol syndrome.

Tthroughout adolescence, the frontal cortex undergoes substantial reorganization, and imaging studies in humans suggest that the frontal cortex may be particularly sensitive to alcohol; likewise, studies in adolescent rodents have reported that chronic alcohol use causes persistent neuronal and cognitive deficits. Brain imaging studies in rats have found that adolescent alcohol exposure decreases cortical functional connectivity, glucose metabolism, and brain growth trajectories. [11]

Furthermore, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies in rats show that acute alcohol exposure alters large-scale brain networks. The effects of alcohol on those networks may vary by sex and age. [11]

Trauma is the leading cause of mortality in children, and ethanol use is linked to a 3-fold to 7-fold increased risk of trauma. Ethanol use is also strongly linked to other risk-taking behaviors that can lead to minor trauma, assault, illicit drug use, and teenage pregnancy. Approximately 40% of the 10,000 annual nonautomotive pediatric deaths (usually drownings and falls) are associated with ethanol.

The concomitant use of ethanol and other drugs is common, and combinations of ethanol with other sedative-hypnotics or opioids may potentiate the sedative effects.

Ethanol greatly increases the risk of trauma, especially trauma due to motor vehicle collisions or violent crimes. In a study of 295 pediatrics patients aged 10-21 years presenting to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of any type of injury, Meropol et al found that 15 patients tested positive for alcohol; however, only 4 of these patients were tested upon initial ED evaluation. [12] Additionally, alcohol is frequently linked with injuries secondary to assault and motor vehicle crashes.

The intoxicated individual often engages in high-risk activities, despite the fact that his or her reflexes are substantially slowed. Adolescent binge drinking has been linked with high-risk behaviors such as riding in cars with intoxicated drivers, sexual activity, smoking cigarettes/cigars, suicide attempts, and illicit drug use. [13] Early alcohol use has been linked to dating violence victimization, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. [12]

Patient Education

Parents should be taught to prevent accidental ingestion at home by storing ethanol-containing liquids out of the reach of children and by disposing of unfinished alcoholic beverages.

Educating adolescents about alcohol abuse has proved challenging. Few data indicate that educational programs to control drinking among adolescents are effective. However, the parents or pediatrician should still educate the patient about the dangers of alcohol consumption, including fetal alcohol syndrome from drinking during pregnancy.

The use of 12-step programs for recovery from alcohol use disorder is not as well studied in adolescents as in adults. Nevertheless, existing research has shown that adolescents may benefit from participation in 12-step groups, and there are 12-step groups specifically designed for young people. Potential barriers to the success of 12-step programs in adolescents include low recognition of their use problem (as adolescents typically have shorter history of substance use than adults and have experienced fewer consequences of it) and certain developmental characteristics of adolescence (limited insight, limit testing, need for autonomy). [14]

Only one half of adolescent alcohol and drug users comply with directives to attend aftercare or 12-step program meetings. However, approximately one third of those who do not attend such meetings have used other methods to minimize or eliminate their drinking, using their own methods; exactly what these methods are has not been well studied. This is an area that may benefit from further study in order to design more effective treatment programs. [15]

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provides a range of printed and online material for professional and patient education regarding youth alcohol use.

-

The pathway of ethanol metabolism. Disulfiram reduces the rate of oxidation of acetaldehyde by competing with the cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) for binding sites on aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).