Practice Essentials

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a tick-borne infection caused by an intracellular bacterium named Rickettsia rickettsii. RMSF is the most common rickettsial disease in the United States. [1] The hallmark of disease process is vasculitis. RMSF is a serious infection with a case-fatality rate of about 10% if left untreated.

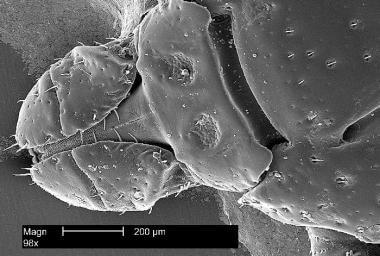

Under a magnification of 98X, this scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts the dorsal view of the head region from an American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, magnified 98X. D. variabilis is a known carrier of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) caused by the bacterium, Rickettsia rickettsii. Courtesy of the Public Health Image Library (PHIL), CDC, photo credit Janice Haney Carr.

Under a magnification of 98X, this scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts the dorsal view of the head region from an American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, magnified 98X. D. variabilis is a known carrier of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) caused by the bacterium, Rickettsia rickettsii. Courtesy of the Public Health Image Library (PHIL), CDC, photo credit Janice Haney Carr.

Signs and symptoms

Incubation period is 2-14 days, with a median of 4 days.

Most affected children are quite ill. The disease results from direct small vessel injury and presents as follows:

-

Fever (range of 40ºC or 104ºF is typical)

-

Severe headache

-

Characteristic rash

-

Myalgias

-

Severe malaise

-

Earlier in the disease course, gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain may be predominant, suggestive of gastroenteritis or even a surgical abdomen

Physical findings include the following:

-

Rash: Appears in 90% of affected children between day 2 and 4 [2]

-

Conjunctival injection: Seen in 33% of cases

-

Altered mental status (33%)

-

Lymphadenopathy (29%)

-

Peripheral edema (25%)

-

Less common: Hepatosplenomegaly, meningismus, or coma

See Presentation for more detail.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) rash in a child. It appears day 3-5 of illness, begins in ankles and wrists, and typically involves palms and soles. In early stages it is macular and later it is petechial. Courtesy of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), CDC.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) rash in a child. It appears day 3-5 of illness, begins in ankles and wrists, and typically involves palms and soles. In early stages it is macular and later it is petechial. Courtesy of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), CDC.

Diagnosis

Screening

Screening laboratory testing may reveal the following:

-

Complete blood cell count may show anemia and/or thrombocytopenia (observed in 5-30%)

-

Complete metabolic panel may show hyponatremia (50%)

-

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis may show pleocytosis in one third of the patients, with either lymphocytic or polymorphonuclear predominance

Confirmatory testing

The most widely used test is immunofluorescence assay (IFA). A 4-fold increase in titers is confirmatory between acute and convalescent stages (collected 2-6 weeks apart). A probable diagnosis can be made based on a single IFA titer of ≥1:64. The sensitivity is low in the first 10-12 days of illness. However, the test is 94% sensitive by 14-21 days. [3]

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for RMSF is less established but is useful earlier in the disease course from blood or tissue samples.

Skin biopsy from the petechial rash during acute illness can be sent for immunohistochemistry; it is 100% specific and 70% sensitive.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

RMSF is a life-threatening illness, and antibiotic therapy should not be delayed in a child with consistent clinical features and epidemiology while awaiting confirmatory testing. Doxycycline is the treatment of choice for all ages. New evidence supports the use of doxycycline for a short course without the risk of teeth staining. Management with doxycycline before 5 days of illness significantly reduces hospitalization, ICU stay, and complications.

The majority of children defervesce within 1-2 days of starting doxycycline. Lack of improvement by 72 hours suggests the need to reconsider the diagnosis even in children with multiple organ involvement. Doxycycline should be continued for 3 days after improvement, and the usual course is 7-10 days.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most common rickettsial infection and the second most commonly reported tick-borne disease (after Lyme disease) in the United States. RMSF is a member of the spotted fever group of rickettsial infections. RMSF gets its name from the initial epidemiological description in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States. It is a reportable disease in the United States to state or local health departments.

The causative agent is Rickettsia rickettsii (named after Howard T. Ricketts, the discoverer of the organism).

RMSF was first described in the late 1800s in the Bitterroot Valley of Idaho, and for several decades, the disease was thought to be limited to the Rocky Mountain area; however, it now has a high documented prevalence in the eastern United States. More than 60% of cases are reported in five states (North Carolina, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri).

The disease is spread mainly through the bites of infected ticks. The dog tick, wood tick, and Lone Star tick are all potential vectors and are responsible for RMSF in different parts of the United States. The distribution of RMSF disease parallels tick activity during peak season.

RMSF has the highest mortality of any tick-borne illness in the United States (up to 30%). Because of this, the Rocky Mountain Laboratory was established in Hamilton, Montana, to help investigate the disease. This laboratory is now part of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Early treatment is critical to the outcome in RMSF and must be started on the basis of clinical diagnosis. Consider the possibility of RMSF in any child with potential tick exposure who develops fever, myalgia, or headache, even if they do not have a rash. If suspected, promptly begin antibiotic (doxycycline) treatment even before confirmation of the diagnosis, as delay in the initiation of treatment is associated with significantly higher mortality.

For additional discussion of the disease, see Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. For patient education information, see the Bites and Stings Center, as well as Ticks.

Pathophysiology

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a diffuse, small-vessel vasculitis. R rickettsii is a small (0.1-0.3 μ) nonmotile gram-negative, obligate intracellular coccobacillus, with a tropism for human endothelial cells.The plasma membrane of mammalian cells, expresses Ku70, which serves as a receptor for the outer surface proteins of OmpA, OmpB and sca 1 for R rickettsii attachment and subsequent phagocytoses by the host cell. It resides in the cytosol and less commonly in the nuclei of the host cells and divides via binary fission. This bacterium causes membrane disruption and increased permeability.

Possible mechanisms for cellular injury include injury to the cell membrane, depletion of adenosine 5-triphosphate (which leads to failure of the sodium pump), and damage to the cell caused by toxic products of rickettsial metabolism.

Vascular lesions are responsible for the clinical manifestations, including rash, headache, alteration in the level of consciousness, heart failure, and shock. Vascular lesions can be found throughout the body, with highest predilection for the skin, gonads, and adrenal glands.

Profound hyponatremia is common. Several mechanisms have been postulated, including a shift in water from the intracellular spaces to the extracellular spaces; increased loss of sodium in the urine; and an exchange of sodium for potassium at the cellular level. [4]

Edema of the medulla oblongata may contribute to fatality in some patients.

Concentrations of antidiuretic hormone and aldosterone are increased in some patients.

Etiology

Ticks are the natural hosts, reservoirs, and vectors of R rickettsii. The species of tick acting as the vector varies by geographic location. R rickettsii is usually transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected tick. On occasion, transmission occurs by scratching or rubbing infectious tick feces into the skin.

Adult ticks transmit the disease to humans during feeding. At least 6 hours of tick attachment is needed for the transmission of R rickettsii.

Primary hosts of R rickettsii include the following {ref16-INVALID REFERENCE}

-

Dermacentor variabilis (dog tick) in the eastern United States and eastern Canada

-

Dermacentor andersoni (wood tick) in the western United States and western Canada

-

Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick) in the southwestern United States

-

Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick) recently implicated as a vector in Arizona

Laboratory personnel can be infected by inoculation or inhalation of aerosolized infectious specimens. For this reason, only specially equipped laboratories should attempt to culture and isolate Rickettsia species. Transmission has occurred on rare occasions by blood transfusion.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

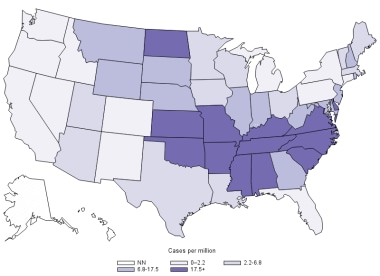

Rocky Mountain spotted fever has been a nationally notifiable condition since the 1920s under the category of Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR). It has been reported in almost every state in the continental United States, with an age-related annual incidence of 0.5-3 cases per million population. [5] In 2000, 495 cases of SFR were reported, while in 2017, more than 6,248 cases were reported, a finding that has been attributed at least in part to increased awareness and testing for the disease, as the percentage of confirmed cases among the total reported, and the case-fatality rate, have both decreased.

Annual incidence (per million persons) for Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR) in the United States, 2017. Courtesy of the CDC.

Annual incidence (per million persons) for Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR) in the United States, 2017. Courtesy of the CDC.

The term Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a misnomer because the disease is relatively rare in the Rocky Mountain states. States reporting the highest rate of disease include North Carolina, Missouri, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Arkansas; these states have accounted for more than half the total cases.

About 90% of cases occur between April and September, the time of the year when ticks have maximal activity and when people participate in outdoor recreational activities.

International statistics

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is also found in Canada, Mexico, Central America, and South America. However, the arthropod vector differs by location. Other rickettsial illnesses similar to Rocky Mountain spotted fever are also found worldwide (see the table below).

Table 1. Human Disease Around the World Caused by Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae. (Open Table in a new window)

Organism |

Disease or Presentation |

Geographic Location |

Rickettsia rickettsii |

Rocky Mountain spotted fever |

North, Central and South America |

Rickettsia akari |

Rickettsialpox |

Worldwide |

Rickettsia conorii |

Mediterranean spotted fever, boutonneuse fever, Israeli spotted fever, Astrakhan fever, Indian tick typhus |

Europe, Asia, Africa, India, Israel, Sicily, Russia |

Rickettsia sibirica |

Siberian tick typhus, North Asian tick typhus |

Siberia, People's Republic of China, Mongolia, Europe |

Rickettsia australis |

Queensland tick typhus |

Australia |

Rickettsia honei |

Flinders Island spotted fever, Thai tick typhus |

Australia, South Eastern Asia |

Rickettsia africae |

African tick-bite fever |

Sub Saharan Africa, Caribbean |

Rickettsia japonica |

Japanese or Oriental spotted fever |

Japan |

Rickettsia felis |

Cat flea rickettsiosis, flea borne typhus |

Worldwide |

Rickettsia slovaca |

Necrosis, erythema, lymphadenopathy |

Europe |

Rickettsia heilongjaiangensis |

Mild spotted fever |

China, Asian region of Russia |

Rickettsia parkeri |

Mild spotted fever |

US |

Race-, sex-, and age-related differences in incidence

Prior to 2000, Native Americans had rates of Rocky Mountain spotted fever similar to those of other races in the United States. [6] From 2001-2005, rates increased disproportionately (16.8 cases per million vs 0.5-4.2 cases per million for other races). The highest rates were in Oklahoma (113.1 cases per million). [7]

Darker-skinned individuals tend to have a worse clinical course, probably due to delays in recognizing the rash. Native American have higher rates of incidence, as well as worse outcomes. The annual incidence of Rocky Mountain spotted fever was 277.2 cases per million in the Southern plains, 104.6 cases per million in the East, and 49.4 cases per million in the Southwest regions. [8] Rates described through the national surveillance network are approximately 5-fold lower than those described in the review by Folkema et al.

The incidence is higher in males than in females, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1. Children are at greater risk of acquiring Rocky Mountain spotted fever than are adults. The highest incidence occurs in children aged 5-9 years. However, the highest mortality is in those aged 50 years or older.

Prognosis

Outcomes can vary from complete resolution to death. The mortality rate during the preantibiotic era was as high as 30%; however, the mortality rate now ranges from approximately 2% in children to 9% in elderly persons.

The outcome greatly depends on the early start of appropriate treatment. The case-fatality rate is higher (6.2%) for persons whose treatment begins more than 3 days after onset of symptoms than for those treated within the first 3 days of illness (1.3%).

The importance of early treatment may help explain the poorer prognosis in African Americans. Rocky Mountain spotted fever may be diagnosed later in Blacks than in people with lighter skin because of the difficulty in detecting the early macular rash. In addition, people with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency tend to have a severe course of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and the prevalence of G6PD deficiency in Black males is 12%.

Severe disease may result in long-term sequelae, such as the following:

-

Partial paralysis of the lower extremities

-

Gangrene requiring amputation of fingers, toes, arms, or legs

-

Hearing loss

-

Blindness

-

Loss of bowel or bladder control

-

Movement disorders

-

Speech disorders

Patient Education

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is a bacterial disease spread through the bite of an infected tick.

Prevention

There is no vaccine to prevent RMSF. Avoidance of illness is by preventing tick bites, preventing ticks on your pets, and preventing ticks in your yard.

Know where to expect ticks. Ticks live in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas, or even on animals, so spending time outside camping, gardening, or hunting will bring you in close contact with ticks.

Treat clothing and gear with products containing permethrin.

Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, oil of lemon eucalyptus (OLE), or 2-undecanone. Do not use products containing OLE or para-menthane-diol (PMD) on children under 3 years old.

After you come indoors, check your clothing for ticks and perform a full body check of yourself and your child's body, particularly at the following areas:

-

Under the arms

-

In and around the ears

-

Inside the belly button

-

At the back of the knees

-

In and around the hair

-

Between the legs

-

Around the waist

Remove the attached tick as soon as you notice it by grasping with tweezers, as close to the skin as possible, and pulling it straight out.

Watch for signs of illness. Most people who get sick with RMSF will have a fever, headache, and rash. RMSF can be deadly if not treated early with the right antibiotic. Timely initiation of doxycycline in children in essential to reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality. A short course of doxycycline is safe even in children younger than 8 years of age.

-

Geographic distribution of Rocky Mountain spotted fever incidence in 2010, cases per million: Courtesy of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

-

Annual incidence (per million persons) for Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis (SFR) in the United States, 2017. Courtesy of the CDC.

-

Under a magnification of 98X, this scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts the dorsal view of the head region from an American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, magnified 98X. D. variabilis is a known carrier of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) caused by the bacterium, Rickettsia rickettsii. Courtesy of the Public Health Image Library (PHIL), CDC, photo credit Janice Haney Carr.

-

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) rash in a child. It appears day 3-5 of illness, begins in ankles and wrists, and typically involves palms and soles. In early stages it is macular and later it is petechial. Courtesy of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), CDC.

-

Tick identification. (i) American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), ii) Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni), and, iii) brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) iv) Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum). Courtesy of the CDC.