Background

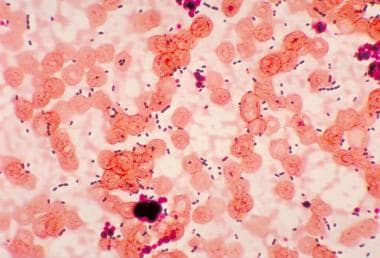

The French word enterocque first was used in 1899 by Thiercelin to describe gram-positive cocci of enteric origin that formed pairs and short chains. Enterococcus species, Streptococcus bovis, and Streptococcus equines originally were grouped together as group D streptococci (Lancefield classification). However, DNA hybridization studies showed that enterococci are biologically, serologically, and genetically different from streptococci, and enterococci now are placed in a separate genus. Enterococcus is currently recognized as one of the most common causes of nosocomial infections and is becoming increasingly resistant to numerous antibiotics, including vancomycin. See the image below.

Pathophysiology

Enterococci are gram-positive, catalase-negative, facultative anaerobes that grow as diplococci in short chains. They can be differentiated from other catalase-negative gram-positive cocci by their ability to hydrolyze esculin in the presence of 40% bile salts, grow in 6.5% sodium chloride at 45°C, and produce pyrrolidonylarylamidase (ie, PYR reaction).

The genus Enterococcus includes 17 species. Most human clinical isolates are due to either E faecalis (74-90%) or E faecium (5-16%). Occasionally, human infections can be due to Enterococcus raffinosus,Enterococcus casseliflavus,Enterococcus durans, or Enterococcus avium. Enterococci are normal flora of the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals. They also may be found in oral secretions, the upper respiratory tract, skin, and the vagina.

Enterococci normally inhabit the bowel; thus, determining whether the microbe is a true pathogen or just happens to be associated with an illness is difficult. Enterococcus is frequently isolated from polymicrobial wounds and intra-abdominal and pelvic infections; however, whether enterococci contribute to the pathogenesis of these infections is often uncertain. Clinical trials have demonstrated that patients with such infections recover without any specific antienterococcal therapy. In animal models, injection of enterococci rarely causes peritonitis or subcutaneous infection, but synergy may be observed between enterococci and other organisms (especially anaerobes).

Bacteremia is speculated to occur as a result of translocation or organisms from the gastrointestinal tract and is more commonly seen following removal of large sections of the bowel and with gastrointestinal pathology.

The pathogenesis of enterococcal infections is poorly understood, but several possible virulence factors exist. Hemolysin/bacteriocin is a plasmid-encoded protein that generally is accepted as a virulence factor. Hemolysin causes lysis of human erythrocytes, functions as a bacteriocin, and is active against other gram-positive cocci. This protein has been demonstrated to increase virulence in several animal models.

Aggregation substance is a plasmid-encoded surface protein that causes clumping or aggregation of enterococci. This substance may mediate adherence to urinary tract epithelial cells, resulting in urinary tract infection (UTI), and may promote adherence to endocardial tissue, resulting in endocarditis.

Gelatinase is an extracellular zinc endopeptidase similar to the elastase produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and has been found to be produced by a large percentage of Enterococcus faecalis isolates from hospitalized patients and patients with endocarditis. Enterococcus faecium may have a carbohydrate moiety that makes it resistant to phagocytosis. Enterococcus also contains lipoteichoic acid, which may cause an exaggerated host inflammatory response.

During chemotherapy, an imbalance was noted between colonization of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria in the gut. In pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia, chemotherapy is associated with a 10,000-fold reduction in fecal anaerobes and 100-fold increase in enterococci. [1]

Epidemiology

United States data

Enterococcal infection is the second most common cause of hospital-acquired infection in the United States. Studies have demonstrated an increased incidence of enterococcal bacteremia in the general pediatric population, from 7 cases of bacteremia per 1000 in 1986 to 48 per l000 in 1991. A 12% increase in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) hospital-acquired infections in the ICU was reported in 2004, with a rate of about 28%. [2]

International data

VRE and VRE infection have increasingly become a worldwide public health threat since the condition was first recognized in the mid-1980s. Among 210 bile samples obtained from 2001-2004 from 79 adult liver transplant recipients within 30 days of transplantation, approximately 75% yielded bacterial strains, of which 36% showed enterococci. [3] Among this same cohort, gram-positive organisms constituted about 78% of surgical site infections, and aminoglycoside-resistant enterococci was reported in 24%.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

No racial predilection is noted.

No predilection is reported for either sex, although enterococcal endocarditis is more common in adult men.

Adults are infected more commonly than children (excepting the neonatal period). Most of the literature regarding invasive enterococcal infections in children focuses on the neonatal period and indicates that approximately 50% of newborn infants are colonized with E faecalis by age 1 week. Older children who develop bacteremia have underlying risk factors.

Prognosis

Morbidity/mortality

Neonatal infections are associated with a 6% mortality rate in early onset septicemia, which rises to 15% in late-onset infections associated with necrotizing enterocolitis. In general, enterococcal sepsis is implicated in 7-50% of fatal cases.

-

This photomicrograph reveals cocci-shaped Enterococcus species bacteria taken from a patient with pneumonia.