Practice Essentials

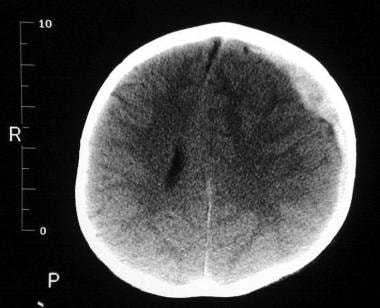

Physical child abuse (or child physical abuse) can result in multiple types of injuries including, but not limited to, cutaneous injuries such as burns and bruises (see the first image below), skeletal injury, abdominal injury, and central nervous system injury (see the second image below). To determine whether a child's injury is concerning for physical abuse rather than accidental injury, the clinician must first determine the full extent of the injury, identify additional, potentially occult injuries, and understand the child's developmental level and abilities. [1]

Signs and symptoms

General physical indicators that should raise concern for inflicted injury include the following:

-

Injury inconsistent with the history provided, especially if incongruent with a patient’s developmental capabilities

-

Injuries at various stages of healing, such as multiple fractures

-

Fractures of high specificity for inflicted trauma, such as classic metaphyseal lesions or posterior rib fractures

-

Sentinel injuries, such as any bruise in a non-ambulatory child, especially infants < 5 months old; oral injuries, such as frenula tears; and subconjunctival hemorrhages in otherwise healthy infants outside of the neonatal period

-

Bruising involving a young child’s ears, face cheeks, buttocks, palms, soles, neck, genitals

-

Patterned bruising, such as grab or squeeze marks, slap marks, spank marks, human bite marks, and marks consistent with implements (eg, loop marks, belt marks, etc.)

-

Patterned contact burns in clear shape of the hot object (eg, fork, clothing iron, curling iron, cigarette lighter, etc.)

-

Forced immersion burn pattern with sharp demarcation, stocking and glove distribution, and sparing of flexed protected areas

-

Localized burns to genitals, buttocks, and perineum (especially during the child's toilet-training phase)

-

Unreasonable and excessive delay in seeking treatment

-

Intracranial hemorrhage, especially subdural hemorrhage, in the absence of a known underlying medical condition

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

History and physical examination findings guide which laboratory and diagnostic imaging studies are performed. Concerns to consider and their corresponding screening tools may include:

-

Bleeding concerns: complete blood count (CBC) with platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), as well as consideration of factor VIII, factor IX, and von Willebrand assays.

Pediatric hematology consultation may be warranted.

-

Bone disease or mineralization defect concerns: serum calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase, as well as vitamin D 25-OH and intact parathyroid hormone levels.

Review of radiographs with a pediatric radiologist is strongly encouraged.

Consultation with pediatric endocrinology and/or genetics may be warranted.

-

Abdominal trauma concerns: screening for abdominal injury is currently recommended in children who present with other injuries eliciting concern for physical abuse, even in the absence of clear external evidence of abdominal injury or abdominal symptoms such as tenderness, distention, or abdominal bruising. Screening includes aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT).

Obtaining other markers of intra-abdominal injury, such as amylase and lipase (pancreatic injury), urinalysis for red blood cells (urinary tract injury), and stool guaiac (intestinal injury) should be guided by history and clinical findings as evidence to support routine screening with these markers is lacking.

-

Toxin or drug ingestion concerns in children presenting with altered mental status: urine and serum toxicology screening with corresponding confirmatory testing.

While hair testing is often brought up as a forensically-relevant method to assess drug exposure, it is not clinically useful and is not recommended in the acute setting.

Consultation with medical toxicology may be warranted.

Quality photodocumentation of cutaneous injuries, such as burns, bite marks, bruises, or other injuries is very helpful in cases of child physical abuse.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Management of child physical abuse is a complex endeavor involving an interdisciplinary team approach. Consultation to a child abuse pediatrician, if possible, is indicated whenever child physical abuse is considered.

The nature of the injury will guide additional subspecialty involvement and related medical therapy, for example:

-

Skeletal fractures of the long bones may require casting; orthopedics should be consulted.

-

Burns vary in severity and treatments range from cleansing the area to skin grafting; plastic surgery should be consulted for more severe burns and transfer to a burn unit may be indicated.

-

The most severely injured children, such as those with CNS injury, may require resuscitation and may need intensive care; a multitude of specialists may need to be involved, including critical care physicians, neurosurgeons, and others.

-

Whenever abusive head trauma is suspected, pediatric ophthalmology warrants consultation; dilated fundus examination to evaluate for retinal hemorrhages and other retinal injuries is indicated.

Psychosocial management complements the medical management and generally requires a significant amount of coordination among various medical providers and community partners. The details of the caregiving environment guide the psychosocial support needed to ensure the child’s safety.

See Treatment for more detail.

Background

Child physical abuse, a subset of child abuse, is defined in various ways. However, common to all definitions is the presence of an injury that the child sustains at the hands of a caregiver. These injuries are also commonly referred to as inflicted or non-accidental injuries. Some US states use broad definitions that encompass a wide range of injuries; other states use more narrow definitions that include specific signs and symptoms. Physical abuse can result in various injuries and injury patterns in children. This article focuses on several common examples of inflicted injury involving the skin (eg, burns, bruises), skeleton (eg, fractures), and central nervous system.

Definitions of physical abuse

The federally funded National Incidence Study (NIS) is a congressionally mandated effort of the United States Department of Health and Human Services to provide updated estimates of the incidence of child abuse and neglect in the United States and measure changes in those estimates. [2] NIS defines physical abuse as a form of maltreatment in which an injury is inflicted on the child by a caregiver via any of various nonaccidental means, including hitting with a hand, stick, strap, or other object; punching; kicking; shaking; throwing; burning; stabbing; or choking to the extent that demonstrable harm results. [3]

The advantage of a specific definition is that it objectively states what is and is not physical abuse; such a narrow scope, however, likely fails to identify all possible cases of physical abuse (eg, pulling the child's hair, biting the child's skin, forcing the child to hold uncomfortable positions for a prolonged period of time, etc.). Definitions may also attempt to characterize the severity of the injury; however, characterization is difficult because injuries vary greatly from, for example, no injury on exam, as physical abuse can at times leave no physical findings, to mild redness on the buttocks due to spanking that fades over several hours, to injuries so severe that the child dies. Newer definitions also aim to consider the sociocultural context in which the injury occurs, while recent medical definitions focus more on the effect of the injury on the child and less on the perceived intention of the caregiver. Importantly, inflicted trauma is consistent with the medical diagnosis of child physical abuse, and the determination of caregiver intent falls outside of the scope of medical practice.

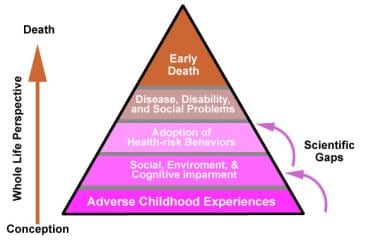

Finally, the effect of physical abuse may not be limited to the immediate injury findings. Long-term physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive issues are known to result from exposure to child physical abuse and other forms of child maltreatment.

Multifactorial nature of physical abuse

No single cause has been identified that explains the occurrence of all cases of child physical abuse, nor have we been able to accurately predict perpetrators of child physical abuse. The multifactorial nature of child physical abuse requires a more comprehensive amalgam of models and conceptual frameworks to account for its heterogeneity.

While attempts have been made to classify circumstances that may give rise to the occurrence of a child's injury via physically abusive actions, they fail to shed light on why those circumstances led to a child's injury in the first place.

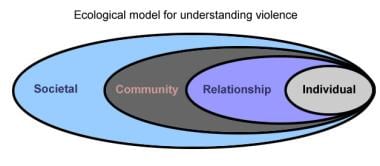

Ecological model of human development and interaction

It is impossible and inadvisable to consider physical abuse of a child as an isolated incident with a single cause and a single effect. The ecological model of human development and interaction is generally regarded as an ideal conceptual framework from which to approach the complex interactions between the caregiver, child, family, social situation, and cultural values contributing to the physical abuse of a child. [4] Note the image below.

The ecological model sees a child functioning within a family (microsystem), the family functioning within a community (exosystem), the various communities linked together by a set of sociocultural values that influence them (macrosystem), and all of these systems operating over time (chronosystem). Each of these system components is interactional in nature, influencing and affecting one another. Similar events have different effects that depend on the period and circumstances in which the event occurs (eg, the child interacts and has an impact on the family, the family influences the child).

Environmental stress and caregiver frustration

Helfer [5] builds on this ecological viewpoint and states that physical maltreatment arises when a caregiver and child interact around a particular event in a given environment with the end result being the injury to the child. Viewing maltreatment in this way allows consideration of the factors that the caregiver, child, and environment contribute to the child’s risk for injury. The caregiver is viewed as having a personal developmental history, personality style, psychological functioning, and coping strategies. Furthermore, the caregiver often has expectations of the child, as well as a particular level of ability to nurture the child's development and subsequently meet the child's developmental and caregiving needs.

The child, in turn, may have certain characteristics that make providing care more complex for a particular caregiver; nonetheless, caution must be used when considering the child's contribution to the abusive interactions. A "difficult" child does not justify abusive treatment by a caregiver. Specific factors that may place the child at higher risk for physical abuse have been found to include prematurity, poor bonding with caregiver, medical needs, various special needs (eg, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), and a perception by the caregiver of the child being “different” (owing to physical, developmental, and/or behavioral/emotional factors) or "difficult" (owing to a child's temperament).

In infants, it is particularly important to recognize crying as a trigger for escalating caregiver frustration. [6] Subsequently, frustration has been described as manifesting in shaking of the crying infant. Research addressing shaking as an attempt to stop infant crying reveals that perpetrators described repeated shaking in more than 50% of cases, occurring daily for several weeks in approximately 20% of cases, prompted in all cases because prior shaking of the infant had reportedly led to a halt in the infant’s crying. Crying, however, has been increasingly recognized as a normal part of infant development. It has been found to increase steadily from approximately the second week of life, peaking at the second month, and eventually receding by the fourth or fifth month of life. This crying curve has been found to coincide with the incidence curve for abusive head trauma. Prevention strategies have subsequently aimed to normalize infant crying during this developmental period and equip caregivers with strategies to anticipate and preventively respond to increasing frustration that may ensue.

Finally, the environment may contain stressors that may make caregiving suboptimal and may overextend the coping abilities of the caregiver. While exploring the role of environmental stress and caregiver frustration in the occurrence of child abuse, Straus and Kantor found a complex interaction between the amount of stress present in the family setting and the response of the caregivers. [7] Importantly, not all stressed caregivers responded by inflicting harm on the children in the environment.

Straus and Kantor concluded that human beings have a capacity for acting violently both in and outside the family setting. Physical abuse can result if a specific situation arises having a relatively high degree of stress and a baseline amount of violence within it (eg, spanking the children, pushing or slapping a spouse). Thus, the risk of child physical abuse is related to the response of caregivers whose caregiving environment has a certain amount of overall risk for violent behavior. The caregivers' level of social connectedness to non-relatives seems to have a role to play in the children's risk for maltreatment. Children whose caregivers were socially isolated and under high degrees of stress were found to have higher rates of child physical abuse than those who were not as socially isolated. However, children whose caregivers had many family members living nearby did not achieve the same protective effect as did the non-familial social-connectedness group.

Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment

The relationship between domestic violence, or intimate partner violence (IPV), and child maltreatment is receiving increasing attention. Each year, millions of children witness episodes of family violence; 30%–60% of mothers of abused children are victims of IPV. Additionally, children whose mothers are victims of IPV are 6 times more likely to be emotionally abused, 4.8 times more likely to be physically abused, and 2.6 times more likely to be sexually abused compared to children living in families in which their mothers are not victims of IPV. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that pediatricians assess for the presence of IPV in the child's family and notes that intervening on behalf of the victimized parent may be an effective child-abuse prevention strategy. [8] Of note, a child’s exposure to IPV between their caregivers carries a significant risk of emotional and psychological harm, and is considered a form of psychological or emotional abuse. Note the image below.

Corporal punishment and child maltreatment

The relationship between the use of corporal punishment and the risk for physical abuse also remains an area of concern. Corporal punishment is defined as a method of discipline that employs physical force as a behavior modifier. Corporal punishment is nearly universal; 90% of US families report having used spanking as a means of discipline at some time. Corporal punishment has its roots in personal, cultural, religious, and societal views of children and how they are to be disciplined. Corporal punishment includes, but is not limited to, pinching, spanking, paddling, shoving, slapping, shaking, hair pulling, choking, excessive exercise, confinement in closed spaces, and denial of access to a toilet.

Discipline is a necessary component for child rearing, and appropriate discipline aims for limit setting, teaching right from wrong, assisting in decision making, and helping the child develop a sense of self-control. However, no reliable evidence in the medical literature supports the continued use of corporal punishment, and corporal punishment has not been found to effectively change undesired behaviors. As a result, the line separating corporal punishment and physical abuse is thin, as corporal punishment carries a significant risk of injury.

When physical force is used as a discipline technique, the concern arises that if the misconduct continues even after corporal punishment is applied, the caregiver may then become angry and frustrated and reapply the physical force. As the physical force is reapplied while the caregiver is becoming increasingly upset, the potential emerges for the caregiver to lose control and injure the child. Regardless of whether injuring the child was the intended outcome of the corporal punishment, the end result experienced by the child is that they have been hurt. Corporal punishment that results in physical injury is generally considered child physical abuse in the United States.

In addition to the risk of physical injury, corporal punishment has been found to be associated with negatively affecting the parent–child relationship, aggressive behaviors, and an increased risk of mental health disorders and problems with cognition.

Caregivers who use corporal punishment are often angry, irritable, depressed, fatigued, and stressed. They typically apply the punishment at a time when they have "lost it," and caregivers frequently describe agitation while punishing their children, followed by remorse. To avoid the risk of harming the child and in order to model non-violent behavior for children, many healthcare professionals advocate child discipline via consistent, non-physical approaches. Approximately one half of US pediatricians report being generally opposed to the use of corporal punishment; about one third are completely opposed to its use. In 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a policy statetement opposing corporal punishment and encouraging a pediatrician–parent partnership to develop non-physical disciplinary techniques based on an evidence-based understanding of normal childhood development. [9]

Pathophysiology

Each type of injury sustained by a child has particular biomechanical elements and pathophysiology. It is important to note that child physical abuse can result in multiple types of injuries involving multiple body systems.

This section will discuss mechanisms of injury and pathophysiology for skeletal injury (ie, fractures), cutaneous injuries such as bruises and burns, intrathoracic and intra-abdominal injury, and CNS injury, given their relatively increased frequency in child physical abuse.

Skeletal fractures

Skeletal fractures are caused by the application of force to the bone. An essential step in the evaluation of skeletal injury in children is determining whether the injury evaluated is consistent with the history provided. This requires appropriate understanding of childhood development, specific characteristics of infant and child bone, and the mechanisms and forces needed to cause specific types of fractures.

The child's immature skeleton is characterized by more porous or trabecular bone than mature bone. Certain fracture types are only seen in developing, immature bone (eg, greenstick fractures, classic metaphyseal lesions, Salter-Harris fractures). The less-dense porous bone tolerates more deformity than adult bone and accounts for the bending and buckling injuries observed with greenstick and buckle fractures in children. The periosteum (the fibrous membrane that covers the bone) is thicker and more easily elevated off the bone in children. The child's joint capsule and ligaments are strong and relatively more resistant to stress than the bone and cartilage, accounting for less joint dislocations and ligamentous tears in childhood. Finally, bone healing is more rapid in children than in adults owing to more rapid bone turnover, which makes dating of childhood fractures more complicated (see Bone Healing and Dating of Injuries below).

While certain types of fractures (eg, posterior rib fractures, classic metaphyseal lesions) are more common and specific for inflicted injury and others are more common in accidental injury (eg, isolated simple skull fractures), there is no fracture that is pathognomonic for child physical abuse. All fractures must be carefully evaluated and correlated in the context of the child's medical history, developmental abilities, the history provided by the caregivers, and the constellation of physical findings.

Fractures can be classified by location in the body (eg, skull vs long bone) and by location on the bone (eg, diaphyseal vs metaphyseal, posterior vs anterior rib).

Specifically in long bones, fractures are described based on location and type, as follows:

-

Physeal fractures, or growth plate fractures, are inherent to children. They result from disruption of the cartilaginous physis, or growth plate, with or without involvement of the adjacent epiphysis or the metaphysis.

The Salter-Harris classification is a commonly used approach to describe these fractures and their extension. Extension of physeal fractures depend on the external force applied; for example, longitudinal forces through the physis will result in a Salter-Harris Type I fracture, while a Salter-Harris Type V results from a crush or compression force to the growth plate.

-

Metaphyseal fractures occur at the section of the bone adjacent to the physis, between the diaphysis and the epiphysis.

The metaphysis is an area of rapid bone turnover in the growing infant and toddler. Metaphyseal fractures are specific to infants as they involve the immature physis.

Planar microfractures through the immature part of the bone edge often appear like chips on radiographs and are known as classic metaphyseal lesions or CMLs (also referred to as corner fractures or bucket-handle fractures). CMLs are caused by shearing and tensile stress such as pulling, twisting, jerking, and rapid acceleration and deceleration forces to the extremity (such as during violent shaking).

-

Diaphyseal fractures are breaks in the shaft of the long bones.

Transverse fractures typically occur when a bending force is applied perpendicular to the long axis of the bone.

Greenstick fractures are incomplete fractures with interruption of the cortex and periosteum typically resulting from bending forces.

Spiral fractures occur when the force applied has a rotational component (ie, torque), with long oblique fractures resulting from a combination of bending and rotational forces.

Buckle fractures (also known as torus fractures) are incomplete fractures resulting from buckling of the cortex due to the application of an axial load onto the long axis of the bone (ie, compression); buckle fractures occur commonly at the transition from diaphysis to metaphysis. Note the images below.

Healing distal femur buckle fracture at 2-week follow-up; note sclerotic fracture line and periosteal new bone formation consistent with healing.

Healing distal femur buckle fracture at 2-week follow-up; note sclerotic fracture line and periosteal new bone formation consistent with healing.

The skull bones differ from long bones in that they develop within a membrane rather than from cartilage. Skull bone fractures typically result from blunt trauma to the head with a solid surface or object. Skull fractures often occur at or near the site of impact, however, owing to unique architectural features of the infant head, a single impact may result in bilateral, typically parietal, fractures or fractures remote from the site of impact. Skull fractures are common injuries in both accidental and inflicted injury. However, significant and clinically evident intracranial injury is more commonly found in cases of abuse (see CNS injury and Abusive Head Trauma below), while small, focal intracranial hemorrhage or injury without significant neurological symptoms is more common to accidental injuries. The advent of head CT 3D reconstruction has improved our recognition and characterization of skull fracture complexity. Determining the etiology of skull fractures requires a comprehensive contextualization of the history provided and assessment of additional clinical findings. The morphology of the skull fracture is typically insufficient to determine physical abuse.

Ribs are common sites of fractures resulting from inflicted trauma (ie, physical abuse), particularly in infants. Posterior rib fractures, adjacent to the vertebral body, elicit particularly high concern for physical abuse. These fractures typically result when the rib levers over the adjacent transverse process of the vertebra during forceful anteroposterior chest compression (ie, squeezing). Contiguous rib fractures (fractures involving > 1 ipsilateral rib), bilateral rib fractures, and multiple rib fractures in different stages of healing should also elicit significant concern for child physical abuse. Direct blunt trauma to the ribs may also result in rib fractures. Careful understanding of the relationship between the location along the rib and the mechanism of injury is important when determining whether the history provided is consistent with the fracture identified.

Bone healing and dating of injuries

Dating of bony injuries is a particularly important concept in the evaluation of child physical abuse because it may assist investigators in determining who had access to the child during the time period over which the injury is estimated to have occurred. The body of medical literature evaluating the precision of dating of fractures has evolved over the last decade. The classic teaching has been that fractured long bones, clavicles, and ribs heal in a predictable fashion, progressing through stages of subperiosteal new bone formation, soft and hard callus formation, and eventually, remodeling.

This traditional description of bone healing includes general timelines for the estimated age of the injury based on the stage of healing seen at the time of injury identification. In young children, bone healing tends to occur more rapidly than in older children and adults. Newer studies of dating of fractures emphasize that the classic descriptions (eg, soft callus, hard callus) are based on histologic specimens rather than radiologic images, and significant inconsistencies exist among radiologic interpretations of healing phases. [10]

Attempts have been made to characterize radiological features of fracture healing and generate more clinically relevant guidelines. Subperiosteal new bone formation is unlikely radiographically evident prior to 7 days after an injury, while callus formation typically becomes evident between 10 and 14 days, progressing over approximately 1–2 weeks. The remodeling phase is highly variable, however. In infants, long bone fractures have been found to appear radiologically remodeled by 3 months after the injury. However, beyond infancy, the timeframe is less predictable and is influenced greatly by multiple fractures, including the fracture type, location, and severity, as well as repetitive trauma to the fracture either due to repeated abusive events or handling of an injured infant prior to identification of the fracture. [11]

Metaphyseal fractures, specifically classic metaphyseal lesions (CMLs), differ from long bone fractures and are generally more difficult to date given the relative lack of disruption in the periosteum at the time of the fracture. This may frequently result in an absence of typical healing features such as callus formation. Similarly, skull fractures heal differently than do long bones because of their intramembranous nature and do not heal with significant callus formation either. While scalp swelling has been frequently associated to fracture acuity, it is neither a precise or universally consistent marker. [12] Recent research has suggested that skull fracture healing or fracture resolution in children ≤ 24 months old ranges broadly from weeks to months. [13]

The evaluation of the healing process on radiographs permits a broad level of fracture dating and allows the healthcare professional to at least generally distinguish between acute and healing fractures in the same child. However, providers should exercise caution if attempting to more precisely date fracture age based on radiological findings alone. Close collaboration with an experienced pediatric radiologist is crucial when dating skeletal injuries in the evaluation of child physical abuse, and clarity regarding the limitations of fracture dating should be made clear to investigators.

Burns

Burns are injuries to the skin or other tissue primarily caused by heat (thermal burns), and arise from various heat sources such as hot liquids (scald burns), hot objects (contact burns), and flame (flame or flash burns). Other types of burns may result from chemicals, friction, radiation, and electricity.

This section will focus on thermal burns considering they are the type of burn most commonly seen in child physical abuse. However, it is important to recognize that other relatively less common types of burns can also be seen as a result of child abuse. For example, inflicted chemical burns and microwave burns have been previously reported.

Human skin is composed of 3 layers: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Burns are classified clinically depending on the depth of the injury and the involvement of the various skin layers. Superficial burns, which involve injury only to the uppermost tissue of the epidermis, present as red, painful areas without blisters. Complete healing without scarring is expected from superficial burns. Deeper burns that extend through the epidermis into the upper levels of the dermis are referred to as partial-thickness burns and present as painful blistering and weeping areas. Healing of partial-thickness burns varies, with different degrees of scarring depending on the involvement and extension of tissue damage. Finally, the deepest burns, full-thickness burns, extend past the epidermis and dermis into the subcutaneous tissue and fat. These burns essentially have destroyed the overlying skin, blood vessels, and associated nerves and present as white, insensate areas because of this destruction. A high degree of scarring and disfigurement typically results from full-thickness burns and significant medical and surgical management can be expected. While discrete classification is helpful, it is important to recognize that clinically, these burn classifications may overlap.

Additionally, three concentric zones of affected tissues that help contextualize a burn injury’s pathophysiology have been described (see Thermal Burns). These zones involve both the superficial area of the burn as well as the underlying affected tissues. The zone of coagulation is the area in most direct contact with the heat source. In this zone, the skin undergoes immediate coagulation necrosis as its proteins denature, blood flow is limited, and cellular repair is no longer possible. The zone of stasis involves less heat energy exposure than that in the zone of coagulation. In the zone of stasis, while blood flow is decreased and these cells are injured, they retain potential for repair. Management goals must aim to restore adequate perfusion to prevent further expansion of the burn wound, avoiding further tissue injury and loss. The zone of hyperemia is the outermost zone of the burn and the zone with least direct injury. Therefore, these cells have the greatest potential for repair. This zone is characterized by increased perfusion secondary to vasodilation and the influx of inflammatory mediators.

All of these burn types and depths can be encountered in both inflicted and accidental burns in children. Evaluation of burns concerning for inflicted injury in children must include, as with any injury, a detailed history from the caregiver and child (if verbal), including a developmental history to determine the child’s capability of contributing to the injury (eg, "turned on the faucet," “climbed into the sink”). Physical examination should include assessment of the burned area. In scald burns, for example, understanding the time it takes for a certain burn to develop may be particularly helpful to determine the consistency of the history. However, while studies aimed at determining time to burn injury have been helpful, determining the time to injury or the age of the burn remains broadly imprecise. Critical assessment of the burned versus spared areas of skin can also be helpful in determining the position of the child at the time of the burn. Note the image below.

Series of 3 photos of likely accidental hot water scald burn on the leg of an infant. Sparing of skin-to-skin contact areas indicates child was flexed at the knee and ankle at the time of injury, which was consistent with being seated in the kitchen sink. Burn injuries require detailed scene investigation. In this case, investigators confirmed the ease of turning on the faucet and the high temperature of the water from it.

Series of 3 photos of likely accidental hot water scald burn on the leg of an infant. Sparing of skin-to-skin contact areas indicates child was flexed at the knee and ankle at the time of injury, which was consistent with being seated in the kitchen sink. Burn injuries require detailed scene investigation. In this case, investigators confirmed the ease of turning on the faucet and the high temperature of the water from it.

Careful gathering of information about what the child was wearing at the time, the time elapsed since the burn, symptom progression, and any topical treatments to the area is important when assessing the burn. Many childhood burns involve hot water in bathtubs or heated liquids in a kitchen setting. Scene investigations by child protective services or law enforcement can gather important information that may help in differentiating concerns between accidental and inflicted injury (eg, temperature of tap water, height of faucets from floor, ease of turning handles, food residue on clothing or at the scene, etc.). [14] Some states in the United States fund public health nursing programs that conduct home safety evaluations to ensure adequate heater temperatures and address home hazards when concerns do not particularly warrant child protective services or law enforcement involvement.

Particular characteristics of the burn can help determine the consistency of the history provided. For example, histories involving spills typically result in flow pattern scald burns, while inflicted immersion burns may result in sharply demarcated burn edges, glove and stocking patterned burns, and doughnut-hole sparing over the buttocks. Similarly, both accidental and inflicted contact burns often reflect the object that caused the injury. Note the image below.

Pattern contact burn on buttocks of diapered child. The burn likely came from the metal grate surrounding heater.

Pattern contact burn on buttocks of diapered child. The burn likely came from the metal grate surrounding heater.

An understanding of the child’s developmental abilities, a detailed history, and clarification of the burn type and extent is important for a thorough assessment and can help address concerns for inflicted injury as well as guide management and prognosis.

Bruising

Bruising occurs when a blunt mechanical force is applied to the skin to such a degree that capillaries (and potentially larger vessels) become disrupted resulting in the leakage of blood into the subcutaneous tissue. The amount and depth of extravasated blood as well as the size and location of the involved area accounts for the evolving appearance of the bruise. If force is applied via an object, the bruise may reflect the shape and geometry of the object. Similarly, patterned bruising may also reflect the mechanism of injury (ie, patterned bruising consistent with a grab, squeeze, spank, slap, or pinch).

In general, a bruise progresses through a series of colors that emanate from the breakdown of the extravasated blood into the components of hemoglobin. As the extravasated blood organizes itself and is resorbed, certain patterns of color change are expected; however, caution is advised because no clearly predictable chronology can be relied on with certainty. Attempting to date bruises by their color or appearance has been strongly discouraged, as data have consistently indicated that color is a poor predictor of bruise age. [15]

Intrathoracic and intra-abdominal trauma

Intrathoracic and intra-abdominal organ injuries often result from direct blunt trauma or transmitted acceleration-deceleration forces, and while less common, these injuries carry significant morbidity and mortality.

Intra-abdominal injury is more common than intrathoracic injury, considering the protective feature of the rib cage, which is often involved in inflicted injury (ie, rib fractures). When present, cardiac and pulmonary contusions suggest blunt trauma to the chest. Disordered conduction such as commotio cordis can result from blunt trauma as well. The liver and the spleen are the most frequently involved intra-abdominal organs, although hollow viscus injury is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, often resulting from high-energy, focal impacts.

CNS trauma

CNS injury typically refers to injury of the brain and spinal cord, and is defined as either primary or secondary injury. Primary injury results from mechanical distortion of the underlying tissue at the moment of the trauma and is due to either a contact or inertial mechanism of injury. Contact injury results from skull deformation due to cranial impact, while inertial injury results from head rotational acceleration-deceleration forces either transmitted via the neck or subsequent to cranial impact. Children who sustain CNS trauma, particularly due to physical abuse, may present with a combination of contact and inertial primary injuries. Primary CNS injury subsequently initiates metabolic cascades that contribute to secondary CNS injury resulting from inflammation, ischemia, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and cell death.

CNS primary injury often involves intracranial hemorrhage, including epidural hemorrhage, which is bleeding into the space between inner skull bone surface and the dura, frequently due to a direct injury to the middle meningeal artery; subdural hemorrhage, which is bleeding into the potential space between the inner surface of the dura and arachnoid membranes, typically caused by shearing of the bridging vessels that connect that brain surface to the dura; and subarachnoid hemorrhage, which is bleeding into the space between the inner surface of the arachnoid and the brain surface. Subpial hemorrhage involves hemorrhage between the pia matter and the cortical surface. It is increasingly recognized given advances in neuroimaging modalities but can be challenging to differentiate from subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Dating CNS injuries carries significant challenges. The appearance of blood, or attenuation, on CT is not a reliable indicator of injury timing. Brain MRI may be helpful in characterizing radiological features that suggest chronicity, such as membrane formation. However, caution should be exerted if attempting to draw a specific injury timeframe based on radiological findings. Close discussion with a pediatric radiologist - preferably a pediatric neuroradiologist - is strongly encouraged. [16] The clinical presentation is particularly important and can often assist in estimating timing. While epidural hemorrhages often are described as having a clinical “lucid-interval,” this is not typical of subdural hemorrhage, particularly considering the mechanisms of injury most often involved in inflicted trauma. Research suggests that patients who present markedly altered or symptomatic (ie, seizures, respiratory compromise) typically have suffered the injury shortly or immediately prior to neurological deterioration, and those with more subtle presentations are typically "not acting normal” after their injury. [17]

Other CNS injuries include parenchymal contusions (ie, direct injury to the brain tissue, typically due to blunt trauma) and intraparenchymal bleeding (ie, bleeding directly into brain matter or parenchyma). These primary injuries can be obscured or complicated by anoxic brain injury and brain edema, which are frequently seen in complex head injury, whether accidental or inflicted. CNS trauma is among the most serious forms of injury observed in the context of physical abuse.

Abusive head trauma (AHT)

Discussing CNS injury and physical abuse inevitably leads to a discussion of abusive head trauma (AHT), [18] previously referred to by multiple other names including shaken baby syndrome (SBS) or shaking-impact syndrome. The mechanism of injury involves rotational acceleration-deceleration and shearing forces to the child’s developing brain tissue (ie, shaking) with or without associated head impact, and has been consistently supported by perpetrator statements. [19, 20] Such forces exceed those generated in normal handling and are different from the low-velocity translational forces (linear movement) that commonly occur in household falls.

Retinal involvement is commonly associated with AHT, and often manifests as retinal hemorrhages with or without retinoschisis. Vitreoretinal traction and acceleration-deceleration forces, particularly in the setting of repetitive trauma, are believed to be the driving mechanisms of injury. Extensive, too-numerous-to-count retinal hemorrhages involving multiple layers of the retina and extending out to the ora serrata are not common to accidental injury, and are instead more frequently identified in cases of AHT. Retinoschisis (spliting of the retinal layers) and macular folds are also more commonly described in AHT in association with retinal hemorrhages. However, there is no pathognomonic retinal finding for AHT and eye findings should be considered within the constellation of historical and clinical findings.

The original description of AHT (referred to as infant whiplash-syndrome at the time) described a clinical constellation of findings classically involving subdural hemorrhage, retinal hemorrhages (found in 65%–95% of cases), and skeletal fractures, such as classic metaphyseal lesions and posterior rib fractures (found in 30%–70% of cases), all of which are consistent with shearing forces during violent shaking. Although AHT is often associated with the findings listed above, no single injury or combination of findings is pathognomonic. Rather, the constellation of clinical findings in the context of the history provided warrants close evaluation to support the diagnosis. At times, however, the diagnosis may remain uncertain, with findings insufficient to completely support or exclude AHT.

Since AHT was first described, a substantial amount of research has upheld the specificity of various clinical findings and shaking has been recognized as a dangerous and potentially lethal mechanism of injury. While courtrooms have challenged these conclusions given limitations in biomechanical, computational, and animal models, it is important to note that there is no significant controversy regarding the recognition of AHT within the medical field and the validity of AHT as a medical diagnosis has been supported by major national and international professional societies. [21]

Epidemiology

Frequency

Child abuse and neglect is common, reportedly affecting at least 1 in every 7 children in the United States in 2019 and accounting for 1820 deaths in 2021. [22] In order to understand the scope of child physical abuse, it is important to understand how the incidence of child maltreatment is determined.

Data from child protective services (CPS) agencies reveal that, in 2021, approximately 3.9 million reports involving 7.1 million children were made. Of these, 54.2% were accepted as needing further investigation, and once evaluated, the investigations concluded that child abuse and neglect had affected approximately 600,000 children, with 16.0% of this total representing cases of substantiated physical abuse. In keeping with prior data, the most common form of substantiated abuse in 2021 was child neglect, which accounted for 76.0% of cases. Child sexual abuse followed, accounting for 10.1% of cases. Notably, multiple forms of child maltreatment, such as emotional and physical abuse, often co-exist. [22]

One important source of epidemiological data is the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data Systems (NCANDS), a voluntary data collection system that gathers information from child protective service agencies in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. These data allow examination of child maltreatment trends and are reported annually in reports to congress and in the Child Maltreatment report. Another important epidemiological data source is the National Incidence Study (NIS), last updated in 2010. The NIS views maltreated children who are investigated by CPS agencies as representing only the "tip of the iceberg." In the NIS methodology, children investigated by CPS are included along with maltreated children who are identified by "sentinels" or community professionals by using data gathered from a nationally representative sample of 122 counties. Sentinels in these counties report data about maltreated children identified by the following organizations: elementary and secondary public schools; public health departments; public housing authorities; short-stay general and children's hospitals; state, county, and municipal police/sheriff departments; licensed daycare centers; juvenile probation departments; voluntary social services and mental health agencies; shelters for runaway and homeless youth; and shelters for victims of domestic violence. CPS agencies in these counties provide data about all children in cases they accept for investigation during 1 of 2 reference periods (for example, September 4, 2005 through December 3, 2005, or February 4, 2006 through May 3, 2006).

Estimating the extent of maltreatment is complex and challenging as the relatively strict criteria used by the NIS-4 generally requires that an act or omission result in demonstrable harm in order to be classified as abuse or neglect; this is denoted as the “Harm Standard” by the NIS. In addition to the Harm Standard, the NIS-4 also reported on the Endangerment Standard, which encompasses those children who meet the Harm Standard as well as those who were not physically harmed by abuse or neglect but that had a CPS investigation that substantiated or indicated maltreatment. The Endangerment Standard is slightly more lenient than the Harm Standard in allowing a broader array of perpetrators, including adult caretakers other than parents in certain maltreatment categories as well as teenage caretakers as perpetrators of sexual abuse. In this way, the Endangerment Standard provides a broader, more encompassing view of maltreatment in the United States.

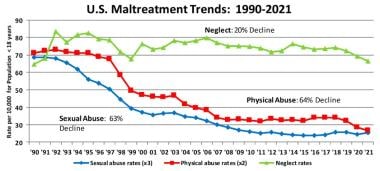

Finkelhor et al analyzed trends in reporting and substantiation rates for child abuse and neglect from the early 1990s through 2021 and identified a declining trend in the number of substantiated cases of physical abuse. According to their most recent analysis, [23] the incidence of substantiated physical abuse cases declined 64% from 1992 to 2021. Cases of child sexual abuse have also declined substantially, with a 63% decrease in the number of substantiated cases of sexual abuse. Child neglect, the most common form of child maltreatment, also showed a 20% decline in substantiated cases from 1992 to 2021. Note the image below.

US Maltreatment Trends: 1990-2021. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, Crimes against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2021. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Published March 2023. Online at: https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/sites/default/files/media/2023-03/updated-trends-2021_current-final.pdf.] (reprinted with permission).

US Maltreatment Trends: 1990-2021. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, Crimes against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2021. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Published March 2023. Online at: https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/sites/default/files/media/2023-03/updated-trends-2021_current-final.pdf.] (reprinted with permission).

While some declines in reports and substantiated cases have been attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, presumably due to children having significantly limited surveillance outside of the home during this period, it is important to understand how these recent declines follow a long-term trend. Finkelhor et al have proposed a number of theories to explain this decreasing trend, including increased investment in law enforcement awareness of child maltreatment, improvements in child protection teams, and a more recent focus on addressing mental health conditions. Trends, however, are known to be dynamic, and trend surveillance is ongoing.

Mortality/Morbidity

Mortality

An estimated 1820 children were known to have died as a result of maltreatment in 2021. Children aged < 3 years accounted for 66.2% of the child abuse and neglect fatalities, with infants younger than 1 year accounting for 45.6% of these cases. Child fatality rates were found to generally decrease with increasing age. When studying the types of maltreatment accounting for the fatalities, the breakdown is as follows:

-

Child neglect - 77.7%

-

Physical abuse - 42.8%

-

Psychological abuse - 2.4%

-

Child sexual abuse - 0.8%

Notably, many of the children who died as a result of maltreatment experienced multiple forms of abuse more frequently. The estimated death rate for child abuse and neglect in the United States is 2.46 per 100,000 children. [22]

Morbidity

Different forms of injury carry different risks. For example, CNS injury and abdominal injury in young children may be particularly serious. Those children that survive serious inflicted injuries, such as abusive head trauma, have variable outcomes that are challenging to prognosticate and may not be fully realized until years following their injuries as they begin to fail meeting expected developmental milestones, develop learning difficulties when starting school, or when behavioral issues become more apparent. Burns observed in child physical abuse cases can range from superficial and self-resolving to full-thickness and severe, requiring grafting and long-term therapy and rehabilitation. Finally, skeletal injuries may be isolated or multiple in nature and may be associated with other injuries. While fractures will generally heal, fractures not brought to prompt medical attention may carry risks of non-union, malalignment, poor healing, and deformity.

Morbidity related to child abuse is not limited to the physical implications of maltreatment. A wealth of literature exists regarding the implications of exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which include child physical or sexual abuse, exposure to family violence, neglect, and other adverse conditions. [24] The major finding of the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies was a graded relationship between the number of adverse childhood experiences, tallied as an "ACE score," and the development of chronic medical and psychiatric illnessess as well as other comorbidities associated with death in adulthood. Note the image below.

It is important to note, however, that although ACEs are important in understanding population risk factors and building prevention strategies, the ACE score has limited utility when applied at the individual level. [25, 26]

Race

A specific racial breakdown for physical abuse was not provided in Child Maltreatment 2021; however, overall racial information for all cases of abuse is as follows: African American (21.5%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (1.5%), Asian (1.0%), Pacific Islander (0.2%), white (42.8%), multiple racial affiliations (6.1%), Hispanic (24.5%), with the remainder of children having unknown or unreported race or ethnicity.

NIS-4 compared 3 major race categories – White (non-Hispanic), Black (non-Hispanic), and Hispanic – and found that White and Black children differed significantly in their rates of experiencing overall Harm Standard abuse during the 2005–2006 NIS-4 study year. An estimated 10.4 cases per 1000 Black children were found to have suffered Harm Standard abuse during the NIS-4 study year, compared with 6 cases per 1000 white children and 6.7 cases per 1000 Hispanic children. The rate of substantiated reports of abuse of Black children is reportedly 1.7 times that of White children and 1.6 times that of Hispanic children. This over-representation of Black children and families has generated significant concern among policymakers and advocates as efforts and interventions to address maltreatment-related factors and social determinants of health disproportionally affecting children of color are urged.

Sex

A specific sex-based breakdown is not provided in Child Maltreatment 2021; however, the overall incidence of child maltreatment was not markedly different in aggregate, with male children accounting for 47.5% and female children accounting for 52.2%, though males are more likely to be fatally injured.

NIS-4 found no significant difference between male and female children’s rates of experiencing serious harm under the Harm Standard. Since the 2006 NIS-3 data, the incidence rates for both sexes declined, but the males’ rate declined more than that of females with reported rates at 33% and 11%, respectively.

Age

A specific age-based breakdown was not provided for physical abuse in Child Maltreatment 2021; however, the overall unique count for substantiated cases by age was as follows: 1–3 years (18.7%), 4–7 years (22.2%), 8–11 years (19.0%), 12–15 years (18.8%), and 16–17 years (6.0%). Children younger than 1 year had the highest rate of victimization overall, accounting for 15.0% of all maltreated children. The victimization rate of children this age is 25.1 per 1000 children.

The NIS-4 incidence of Harm Standard physical abuse is significantly lower for the youngest children (2.5 cases per 1000 children aged 0–2 years) compared with children aged 6–14 years (4.6 cases per 1000 or higher). The relatively low incidence rates for children younger than 2 years may actually reflect a detection problem; because children who are younger than school age are less observable to community professionals, their abuse may avoid detection unless particularly severe or prompting medical attention.

-

Overlap of child maltreatment and domestic violence.

-

Handprint on face. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Handprint on leg. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Patterned bruises inflicted with a belt. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Bruises inflicted with switch. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Bruises inflicted with switch. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Switch. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Bruises inflicted with wooden spoon. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Bruises inflicted with belt. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Buckle fracture of distal femur shaft. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Duodenal hematoma. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Burn from car seat. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Car seat. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Model for femoral neck fracture from being yanked from crib. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Femoral neck fracture from being yanked from crib in previous image. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Inflicted pinch mark shaft. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Burn from being held down on hot cement. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Old and new radius fracture. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Child with slap mark. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Radiograph of old radius and ulna fracture in child with slap mark. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Radiograph of multiple rib fractures. Radiographs also revealed old radius and ulna fracture. The child presented with a slap mark. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Sunburn. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Burn inflicted with lighter. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Subdural hemorrhage with midline shift. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Fingernail scratch in child with acute subdural with shift. Image courtesy of Lawrence R. Ricci, MD.

-

Ecological model for understanding violence.

-

Adverse child experiences pyramid.

-

National Pediatric Trauma Group registry findings.

-

Acute distal femur buckle fracture; note absence of healing.

-

Healing distal femur buckle fracture at 2-week follow-up; note sclerotic fracture line and periosteal new bone formation consistent with healing.

-

Linear inflicted bruising extending from arm to back, inflicted by a belt. Same child shown again with back bruising.

-

Overlying linear inflicted marks, which the child disclosed came from a belt. Same child is shown in image of arm and back.

-

CT scan showing liver laceration. Child had severe abdominal bruising (see next image). Caregiver admitted to repeatedly punching the child in the abdomen.

-

Abdominal bruising in a toddler who also had a liver laceration (also see previous CT scan).

-

Example of ear bruising. Ear bruising is a rare accidental injury. This 10-month-old child was intubated for abusive head trauma (AHT) and spiral femur fracture and had this ear bruising in addition to other facial bruising.

-

Dermal melanocytosis on a child with dark complexion

-

Dermal melanocytosis on a child with light complexion. Dermal melanocytosis color hues may differ depending on the skin pigmentation of the child.

-

Faint abdominal bruising. This toddler had elevated liver function test results, liver laceration found on abdominal CT scan, and an upper lip frenulum tear. Note that abdominal injury may be present with little or no bruising of the abdomen.

-

Pattern bruising and extensive back bruising. The 4-year-old child was found dead in his home and had no reported history. Autopsy revealed duodenal hematoma and perforation as cause of death.

-

Pattern contact burn on buttocks of diapered child. The burn likely came from the metal grate surrounding heater.

-

Series of 3 photos of likely accidental hot water scald burn on the leg of an infant. Sparing of skin-to-skin contact areas indicates child was flexed at the knee and ankle at the time of injury, which was consistent with being seated in the kitchen sink. Burn injuries require detailed scene investigation. In this case, investigators confirmed the ease of turning on the faucet and the high temperature of the water from it.

-

Example of strangulation/ligature marks on the neck of a toddler. Strangulation/ligature marks are often linear petechiae and may have fingernail scratches from the victim from struggling to free the airway.

-

US Maltreatment Trends: 1990-2021. Courtesy of David Finkelhor, Crimes against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire [Finkelhor D, Saito K, Jones L. Updated Trends in Child Maltreatment, 2021. Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire. Published March 2023. Online at: https://www.unh.edu/ccrc/sites/default/files/media/2023-03/updated-trends-2021_current-final.pdf.] (reprinted with permission).