Pearls

Keep the following pearls in mind:

-

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is a common comorbidity of neonates that is mainly associated with the etiologic triad of prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and mechanical ventilation therapy.

-

PIE is mainly a radiologic and pathologic diagnosis. It is associated with few clinical signs, but a progressive, sometimes rapid, increase in O 2 requirements, CO 2 retention, or hypotension are suggestive of this diagnosis.

-

The reported incidence varies widely depending on various factors such as gestational age, use of surfactant therapy, and different modes of mechanical ventilation. In the postsurfactant era, the reported incidence is between 3% and 8%. Clinical research is needed, with a specific emphasis on the incidence of, and outcomes in, PIE in the current era of innovative ventilatory strategies.

-

Although prematurity—the primary risk factor for PIE—is nonmodifiable, attention must be given to judicial treatment of RDS with early administration of surfactant and optimal use of mechanical ventilator support. An often-used strategy is to reduce the inspiratory time and/or decrease pressure along with adjusting the positive-end expiratory pressure (PEEP) enough to stent the airway will allow better emptying of the alveoli during expiration. [1] Close clinical observation by monitoring oxygen need, work of breathing and perfusion status, as well as judicious analysis of blood gas and chest x-ray, are essential to determine an optimal PEEP for a particular infant.

-

Consequences of PIE can be other air leak syndromes, such as pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, or penumopericardium, if not enough attention and management strategies are applied.

-

If PIE develops, various management strategies include lateral decubitus positioning, selective main bronchial intubation and occlusion, and lobectomy for unilateral cases. Studies has shown the benefit, safety, and effectiveness of high frequency jet and oscillatory ventilation; it is been shown to reduce the peak airway pressure (P IP) and mean airway pressure (MAP) requirements to achieve the same oxygenation and ventilation goals.

Background

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is a collection of gases outside of the normal air passages and inside the connective tissue of the peribronchovascular sheaths, interlobular septa, and visceral pleura. This condition develops when the most compliant portion of the terminal airway ruptures, allowing gas to escape into the interstitial space. [2] Pulmonary interstitial emphysema essentially, if not exclusively, occurs in preterm infants with immature lungs, usually after mechanical ventilation therapy, [3, 4, 5] but occasionally in the absence of mechanical ventilation. [6, 7, 8, 9] PIE is broadly classified under pulmonary air leak syndromes.

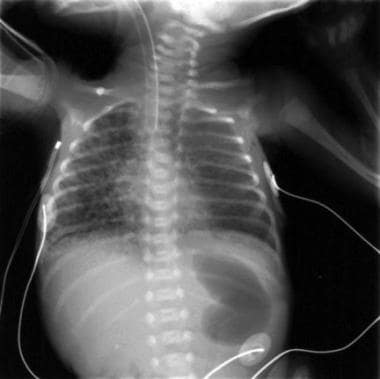

PIE is a radiographic and pathologic diagnosis (see image below and Workup). The introduction of surfactant and newer ventilator modalities has decreased the incidence of PIE. Its treatment of PIE is mainly preventive by using the minimum pressures or volume compatible with an acceptable gas exchange as well as early administration of selective surfactant, if indicated, to infants with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Therefore, minimizing the use of invasive ventilator support and favoring spontaneous ventilation under nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is probably the best preventive measure. The principal therapies are lateral decubitus positioning, selective intubation, and occlusion of the contralateral bronchus, in conjunction with high-frequency or jet ventilation. [3, 4, 10] Intensive respiratory management is required to reduce morbidity and mortality in these patients.

This radiograph, obtained from a premature infant at 26 weeks' gestation, shows characteristic radiographic changes of pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) of the right lung.

This radiograph, obtained from a premature infant at 26 weeks' gestation, shows characteristic radiographic changes of pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) of the right lung.

See the Medscape Drugs & Diseases articles Imaging in Pulmonary Interstitial Emphysema, Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Respiratory Distress Syndrome Imaging, Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia, and Imaging in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia for more information on these topics.

Pathophysiology

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) is initiated when air ruptures from the alveolar air space and small airways into the perivascular tissue of the lung. Air leaks result from high intra-alveolar pressure more frequently due to mechanically applied pressure (insufflation), retention of large volumes of gas, and uneven ventilation, leading to rupture of the small airways or alveoli. Transpulmonary pressures that exceed the tensile strength of the noncartilaginous terminal airways and alveolar saccules can damage the respiratory epithelium. Loss of epithelial integrity permits air to enter the interstitium, causing pulmonary interstitial emphysema. The process often occurs in conjunction with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS).

Other predisposing etiologic factors include meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), amniotic fluid aspiration, and infection (which can include chorioamnionitis [11] or congenital pneumonia). The highest incidence of PIE in tiny infants has been observed when intrauterine pneumonia complicates the respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). It is also been reported with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection or other bronchiolitis in term infants which can be mimicked by congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. [3, 12]

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV) and reduced lung compliance are significant predisposing factors. Studies have shown that hyperventilation and overinflation of the lungs increase the loss of surface active phospholipids. [13] However, in extremely premature infants, PIE can occur at low mean airway pressure and probably reflects the underdeveloped lung’s increased sensitivity to stretch. PIE has been rarely reported in the absence of mechanical ventilation or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). [7, 8] Incorrect positioning of endotracheal tube may be responsible for localized PIE. [14]

Infants with RDS have an initial increase in interstitial and perivascular fluid that rapidly declines over the first few days of life. This fluid may obstruct the movement of gas from ruptured alveoli or airways to the mediastinum, thereby causing an increase of PIE. This occurs more commonly in preterm infants due to the structural immaturity of the lung, mainly owing to a lack of elastic tissue and the presence of large interstitium as a result of poor alveolation. The entrapment of air in the interstitium may initiate a vicious cycle in which compression atelectasis of the adjacent lung then necessitates a further increase in ventilatory pressure with still more escape of air into the interstitial tissues.

Plenat et al described two topographic varieties of air leak: intrapulmonary pneumatosis and intrapleural pneumatosis. [15] In the intrapulmonary type, which is more common in premature infants, the air remains trapped inside the lung and frequently appears on the surface of the lung, bulging under the pleura in the area of interlobular septa. This phenomenon develops with high frequency on the costal surface and the anterior and inferior edges, but it can involve all of the pulmonary areas. In the intrapleural variety, which is more common in more mature infants with compliant lungs, the abnormal air pockets are confined to the visceral pleura, often affecting the mediastinal pleura. The air of PIE can be located inside the pulmonary lymphatic network. [16]

The extent of PIE can vary. It can present as an isolated interstitial bubble, several slits, lesions involving the entire portion of one lung, or diffuse involvement of both lungs. PIE does not preferentially localize in any one of the five pulmonary lobes.

PIE compresses adjacent functional lung tissue and vascular structures and hinders both ventilation and pulmonary blood flow, thus impeding oxygenation, ventilation, and blood pressure. This further compromises the already critically ill infant and significantly increases morbidity and mortality. PIE can completely regress or decompress into adjacent spaces, causing pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, pneumoperitoneum, or subcutaneous emphysema. [17]

Etiology

Risk factors for pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) include the following:

-

Prematurity

-

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)

-

Meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS)

-

Amniotic fluid aspiration

-

Infection: Exposure to chorioamnionitis, neonatal sepsis, or pneumonia,

-

Low Apgar score or need for positive pressure ventilation (PPV) during resuscitation at birth

-

Use of high peak airway pressures on mechanical ventilation therapy in the first week of life

-

Incorrect positioning of the endotracheal tube in one bronchus

-

Antenatal exposure to magnesium sulfate [18] : More investigation is needed

Independent risk factors for PIE in preterm infants include higher oxygen requirements during resuscitation as well as greater need for surfactant and higher ventilatory pressures before confirmation of the diagnosis. [5]

Epidemiology

United States data

The prevalence of pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) widely varies with the population studied. In a report by Gaylord et al, PIE developed in 3% of infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). [20]

In a retrospective case-controlled study, 11 (24%) of 45 extremely low birth weight infants developed PIE. [18] This study was done in the present era of tocolysis, antenatal steroids, and postnatal surfactant administration; however, all infants included in the study were treated with a conventional ventilator in the assist-control mode before the onset of PIE.

The reported incidence of PIE in published clinical trials can be useful. In a randomized trial of surfactant replacement therapy at birth in premature infants born at 25-29 weeks' gestation, Kendig et al reported PIE in 8 (26%) of 31 control neonates, and in 5 (15%) of 34 surfactant-treated neonates. [21]

Another randomized controlled trial of prophylaxis versus treatment with bovine surfactant in neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) born at less than 30 weeks' gestation included 2 (3%) of 62 early surfactant-treated neonates, 5 (8%) of 60 late surfactant-treated neonates, and 15 (25%) of 60 control neonates with PIE. [22]

Kattwinkel et al compared prophylactic surfactant administration versus the early treatment of RDS with calf lung surfactant in neonates born at 29-32 weeks' gestation; 3 of 627 neonates in the prophylaxis group and 3 of 621 neonates in the early treatment group developed PIE. [23] This information suggests a higher incidence of PIE in more immature infants as well as those administered with late surfactant therapy.

International data

Studies reflecting the international frequency of PIE demonstrated that 2-3% of all infants in NICUs develop this condition. [11, 24] When limiting the study population to premature infants, the frequency increases to 20-30%, with the highest frequencies occurring in infants weighing less than 1000 g. [25] A trial that compared high-frequency positive pressure mechanical ventilation (HFPPV) with conventional ventilation revealed a 25.8 % and 6.5% incidence of PIE in the respective groups. [26]

In another study of low birth weight infants, the incidence of PIE was 42% in infants with a birth weight of 500-799 g, 29% in those with a birth weight of 800-899 g, and 20% in those with a birth weight of 900-999 g. [27] Unfortunately, minimal information is available about the prevalence of PIE in the postsurfactant era.

In a prospective multicenter trial comparing early high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) and conventional ventilation in preterm infants of fewer than 30 weeks' gestation with RDS, 15 (11%) of 139 infants in the high-frequency group and 15 (11%) of 134 infants in the conventional group developed PIE. [24]

Sex- and age-related demographics

In a study by Plenat et al, PIE developed about equally in both sexes (21 males, 18 females). [15] Although these data also included cases with intrapleural pneumatosis, no relationship between sex and type of interstitial pneumatosis was noted.

PIE is more common in infants of lower gestational age, and it usually occurs within the first weeks of life. That is, development of PIE within the first 24-48 hours after birth is often associated with extreme prematurity, very low birth weight, perinatal asphyxia, and/or neonatal sepsis—and frequently indicates a grave prognosis.

Prognosis

Pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) can predispose an infant to other air leaks. In a study by Greenough et al, 31 of 41 infants with PIE developed pneumothorax, compared to 41 of 169 infants without PIE. [8] In addition, 21 of 41 babies with PIE developed intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), compared to 39 of 169 among infants without PIE.

PIE may not resolve for 2-3 weeks; therefore, it can increase the duration of mechanical ventilation support as well as the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Some infants may develop chronic lobar emphysema, which may require surgical lobectomies. [19]

In a study in the postsurfactant era, 4 of 11 infants with PIE developed severe IVH (grade 2 or higher) compared to 4 of 34 infants without PIE. Additionally, PIE remained significantly associated with death (odds ratio, 14.4; 95% confidence interval, 1-208; P = 0.05). [18]

Long-term follow-up data are scarce. Gaylord et al demonstrated a high (54%) incidence of chronic lung disease in survivors of PIE compared to their nursery's overall incidence of 32%. [20] In addition, 19% of the infants with PIE developed chronic lobar emphysema; of these babies, 50% received surgical lobectomies.

The mortality rate associated with PIE is reported to be as high as 53-67%. [20, 25] Lower mortality rates of 24% and 38% reported in other studies could result from differences in population selection. [8, 11] Morisot et al reported an 80% mortality rate with PIE in infants with a birth weight of fewer than 1600 g and severe respiratory distress syndrome. [28]

The early appearance of PIE (< 48 h after birth) is associated with increased mortality. However, this may reflect the severity of the underlying parenchymal disease. [11, 28]

Complications

Potential complications of PIE include the following:

-

Respiratory insufficiency

-

Other air leaks (eg, pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, pneumopericardium, pneumoperitoneum, subcutaneous emphysema [rare])

-

Massive air embolism

-

Chronic lung disease of prematurity

-

IVH

-

Periventricular leukomalacia

-

Death

-

This radiograph, obtained from a 1-day-old premature infant at 24 weeks' gestation, shows bilateral pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE). Linear radiolucencies extending up to the lung periphery are visible.

-

This radiograph, obtained from a premature infant at 26 weeks' gestation, shows characteristic radiographic changes of pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) of the right lung.

-

This radiograph shows pneumothorax and pulmonary interstitial emphysema (PIE) on the right side. Interstitial air prevents collapse of the underlying lung by a tension pneumothorax. In such cases, extreme caution is required during drainage of a pneumothorax to avoid perforation of the underlying lung.