Practice Essentials

Allergic rhinitis usually presents in early childhood and is caused by an immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated reaction to various indoor and outdoor allergens. An IgE-mediated reaction is when an allergen, that the body has previously recognized and processed to create IgE, is reintroduced. The previously made IgE is attached to a MAST cell and when 2 IgEs on that mast cell attach to the same antigen, it triggers the mast cell to degranulate and trigger the reaction. The degranulation releases mediators such as histamines and leukotrienes. In the case of allergic rhinitis, the reaction takes place in the nasal passages. The reaction is the same for all allergic reactions. Sensitization to indoor allergens can occur in allergic rhinitis in children older than 2 years; however, sensitization to outdoor allergens is more common in children older than 4–6 years. Clinically significant sensitization to indoor allergens may occur in children younger than 2 years, but this is unusual. In the very young, there is a significant chance of a false-positive test, commonly secondary to atopic dermatitis. The most common indoor allergens include dust mites, pet danders, cockroaches, molds, and pollens.

Signs and symptoms

The history of the patient with allergic rhinitis is usually straightforward, but at times may have a complex set of symptoms. The diagnosis is easy to make in a patient with a new pet or with symptoms that have distinct seasonal variation. Alternatively, younger patients may present with varying signs or symptoms, the family may not appreciate the nasal stuffiness, but may note the chronic nasal congestion. At times, a young child presents with what appears as seasonal allergies, when in fact it is a pet allergy, since the dander is shed in the spring and reaccumulates in the fall. In older children, symptoms may have been present for years and, therefore, appear to be less severe, because the child has accommodated them. Also making diagnosis challenging is that symptoms of an upper respirtory illness can mimic allergies, convincing patients that they have an allergy. This is especially true in the fall season with rhinovirus.

Signs and symptoms of pediatric allergic rhinitis include the following:

-

Rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, postnasal drainage

-

Pale nasal turbinates, with or without clear nasal discharge

-

Repetitive sneezing

-

Itching of the palate, nose, ears, or eyes

-

Snoring

-

Frequent sore throats

-

Constant clearing of the throat, cough

-

Headaches

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

A full examination to detect other diseases should be performed. Other diagnoses such as adenoidal hypertrophy, asthma, eczema, gastroesphogeal reflux, and cystic fibrosis, which occur in children in connection with allergic rhinitis, should be suspected. Evaluation of the child involves the head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat, and can include the following:

-

Head: Allergic shiners (dark, puffy, lower eyelids), Morgan-Dennie lines (lines under the lower eyelid), transverse crease at lower third of nose secondary to nose rubbing as in the allergic salute

-

Eyes: Marked erythema of palpebral conjunctivae and papillary hypertrophy of tarsal conjunctivae; chemosis of the conjunctivae, usually with a watery discharge; in severe cases, cataracts from severe rubbing secondary to itching

-

Ears: Chronic infection or middle ear effusion

-

Nose: Enlarged turbinates with pale-bluish mucosa due to edema; clear or white nasal discharge (rarely yellow or green); dried blood secondary to trauma from nose rubbing; rarely, polyps (if polyps detected on rhinoscopy, mandatory workup for cystic fibrosis in children)

-

Throat: Discoloration of frontal incisors, high arched palate, and malocclusion associated with chronic mouth breathing; cobblestoning in the posterior pharynx secondary to chronic nasal congestion and postnasal drainage

Testing

No laboratory studies are needed in allergic rhinitis if the patient has a straightforward history. When the history is confusing, various studies are helpful, including the following:

-

Skin testing: highly sensitive and specific for aeroallergens

-

Allergen-specific IgE: can be helpful if a specific allergen is suspected

-

Serum IgE: elevated IgE value is suggestive of allergic rhinitis; it is not as sensitive as skin-prick testing and thus is rarely used today due to its limited utilty

-

Nasal smear: commonly used in the past, but with present lab regulations it is now rarely performed

Imaging studies

In general, imaging studies are not needed in pediatric allergic rhinitis unless sinusitis is suspected. In such cases, a limited computed tomography scan of the sinuses (without contrast) is indicated.

Procedures

Allergy skin testing is useful to identify suspected allergens. Testing can be done by both skin-prick or intradermal skin testing.

Spirometry maybe considered because as many as 70% of children with asthma have concomitant allergic rhinitis.

Rhinoscopy can be helpful in direct examination of the upper airway for identification of an obstructive versus infectious etiology of the rhinitis and for evaluation of nasal polyposis.

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Treatment of allergic rhinitis can be divided into 3 categories:

-

Avoidance of allergens or environmental controls

-

Medications

-

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (subcutaneous injection or sublingual tablet)

Pharmacotherapy

Many groups of medications are used for allergic rhinitis, including antihistamines, corticosteroids, decongestants, saline, sodium cromolyn, and antileukotrienes. These can be further subdivided into intranasal and oral therapies.

The following medications are used in pediatric patients with allergic rhinitis:

-

Second-generation antihistamines (eg, cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, desloratadine, fexofenadine)

-

Intranasal antihistamines (eg, azelastine, intranasal olopatadine)

-

Intranasal corticosteroids (eg, intranasal beclomethasone, intranasal budesonide, intranasal ciclesonide, intranasal flunisolide, intranasal fluticasone, intranasal mometasone, intranasal triamcinolone)

-

Intranasal antihistamine/corticosteroid (eg, azelastine/fluticasone intranasal; olopatadine/mometasone intranasal)

-

Intranasal decongestants (eg, ipratropium intranasal)

-

Intranasal mast cell stabilizers (eg, intranasal cromolyn sodium)

-

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (eg, montelukast)

Nonpharmacotherapy

The following are management options in allergic rhinitis that don’t involve medications:

-

Allergen-specific immunotherapy: The only form of therapy that can cure allergy symptoms; must be customized to the patient's individual allergies

-

Saline nasal irrigation: Effective in approximately 50% of patients with allergic rhinitis

-

Removal of the trigger, if identified

Surgical option

No routine surgical care is needed for pediatric allergic rhinitis. However, in selected patients, the following surgical intervention may be performed to provide some relief:

-

Adeniodectomy

-

Turbinectomies

-

Nasal polypectomy

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

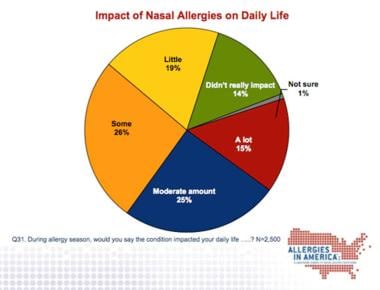

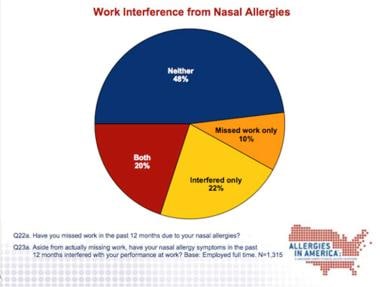

Although allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common disease, the impact on daily life cannot be underestimated. Some patients find AR to be just as debilitating and intrusive as severe asthma. Employees with untreated allergies are reportedly 10% less productive than coworkers without allergies, whereas those using allergy medications to treat AR were only 3% less productive. [1] This suggests that effective medications may reduce the overall cost of decreased productivity.

AR is caused by an immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated reaction to various allergens in the nasal mucosa. The most common allergens include dust mites, pet danders, cockroaches, molds, and pollens. For example, tree pollen allergen binds to IgE antibodies that are attached to a mast cell via Fcε receptor. When 2 IgE molecules bind to the same tree pollen allergen, they cause the mast cell to fire off (degranurate), leading to release of various inflammatory mediators that cause the symptoms we recognize as AR, including sneezing; nasal congestion; stuffiness; rhinorrhea (runny nose); cough; itching of the nose, eyes, and throat; sinus pressure; headache; and epistaxis (bloody nose).

The allergens present in the outdoor environment vary with the time of year and location. Knowing what allergens are in the environment at a specific time of year helps in diagnosing and treating AR and helps in excluding allergy as a cause of the patient's symptoms. For example, a patient who presents with nasal congestion in November in Boston, Massachusetts cannot have allergic rhinitis attributed to tree pollen allergy, which is prevalent in spring.

Allergen exposure likely causes both upper and lower airway inflammation, meaning that both the nose and the lungs may be involved. Many experts believe that a patient's airway needs to be evaluated as a total entity, not as individual parts. It is referred to as the one airway hypothesis. Studies have shown that most pediatric patients with asthma also have AR. Guidelines regarding the impact of AR on asthma have been established. [2] Allergic reactions of the upper airway can trigger lower airway symptoms and vice versa. One study showed that patients with untreated AR and asthma have an almost 2-fold greater risk of having an emergency department visit and almost a 3-fold greater risk of being hospitalized for an asthma exacerbation, respectively. [3] Similarly there are studies that reveal treatment of one disease entity improves the other.

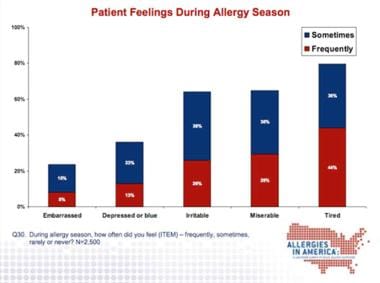

The graphs below detail the significant impact of nasal allergies.

Pathophysiology

Understanding the function of the nose is important in order to understand allergic rhinitis (AR). The purpose of the nose is to filter, humidify, and regulate the temperature of inspired air. This is accomplished on a large surface area spread over 3 turbinates in each nostril. A triad of physical elements (ie, a thin layer of mucus, cilia, and vibrissae [hairs] that trap particles in the air) accomplishes temperature regulation. The amount of blood flow to each nostril regulates the size of the turbinates and affects airflow resistance. The nature of the filtered particles can affect the nose. Irritants (eg, cigarette smoke, cold air) cause short-term rhinitis; however, allergens cause a cascade of events that can lead to more significant, prolonged inflammatory reactions.

In short, rhinitis results from a local defense mechanism in the nasal airways that attempts to prevent irritants and allergens from entering the lungs.

Allergic reactions require exposure and then sensitization to allergens. To be sensitized, the patient must be exposed to allergens for a period of time. Sensitization to highly allergenic indoor allergens can rarely occur in children younger than 2 years. Sensitization to outdoor allergens usually occurs when a child is older than 3–5 years, and the average age at presentation is 9–10 years. The allergic reaction begins with the cross-linking of the allergen to 2 adjacent IgE molecules that are bound to high-affinity Fcε receptors on the surface of a mast cell. This cross-linking causes mast cells to degranulate, releasing various mediators. The best-known mediators are histamine, prostaglandin D2, tryptase, heparin, and platelet-activating factor, as well as leukotrienes and other cytokines.

These substances produce 2 types of reactions: immediate and late-phase. The immediate reactions in the nasal mucosa induce acute allergy symptoms (eg, nasal itch, clear nasal discharge, sneezing, congestion). The late-phase reaction occurs hours later, secondary to the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the tissue by the action of mediators (termed chemokines) released by the mast cell. Recruited cells are predominately the eosinophils and basophils, which, in turn, release their inflammatory mediators, leading to continuation of the cascade. In very sensitive individuals, this allergen-induced nasal inflammation causes priming of the nasal mucosa. Primed nasal mucosa becomes hyperresponsive, at which point even nonspecific triggers or small amounts of the antigen can cause significant symptoms.

Frequency

United States

Prevalence in the United States is 10–20%. [4] One survey demonstrated rates as high as 38.2% when patients were asked if they experienced fewer than 7 days of symptoms. When allergic rhinitis was defined as symptoms lasting more than 31 days, prevalence dropped to 17%.

International

In temperate areas of Europe and Asia, frequency is similar to that in the United States.

Mortality/Morbidity

Mortality is not associated with allergic rhinitis (AR), but significant morbidity occurs. Morbidity is manifested in several ways. Annually, an estimated 824,000 school days are missed, and an estimated 4,230,000 days of reduced quality-of-life functions are reported. [5] Comorbidity of other atopic diseases (asthma, atopic dermatitis) or upper airway inflammation (sinusitis, otitis media) is significant in AR. Individuals with AR have a higher frequency of these conditions than individuals without AR.

Quality-of-life surveys have revealed that patients with significant AR found symptoms to be just as debilitating as symptoms in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma. Patients with AR felt they were equally impaired and unable to participate in the activities of normal living similar to those with the moderate-to-severe asthma. They felt that chronic congestion, sneezing, the need to wipe the nose, and a decrease in restful sleep compromised levels of their daily activity.

The financial cost of AR is difficult to estimate. Self-treating patients are estimated to spend an average of 56 dollars per year. The direct cost of prescription medication exceeds 6 billion dollars per year worldwide, and lost productivity is estimated at 1.5 billion dollars per year.

Epidemiology

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Allergic rhinitis (AR) has no race predilection; however, individuals from nonwhite backgrounds seek out medical attention less often than whites. The incidence is higher in urban and suburban areas versus more rural ones.

AR has no sex predilection.

AR usually presents in early childhood. AR caused by sensitization to outdoor allergens can occur in children older than 2 years; however, sensitization in children older than 4-6 years is more common. Clinically significant sensitization to indoor allergens may occur in children younger than 2 years. This is typically associated with significant exposures to indoor allergens (eg, molds, furry animals, cockroaches, dust mites). Some children may be sensitized to outdoor allergens at this young age if they have significant exposure. Incidence continues to increase until the fourth decade of life, when symptoms begin to fade; however, individuals can develop symptoms at any age.

AR-like symptoms (runny nose, blocked nose, or sneezing apart from a cold) may begin as early as age 18 months. In a report from the Pollution and Asthma Risk: an Infant Study (PARIS), 9.1% of the 1859 toddlers in the study cohort reported allergic rhinitis-like symptoms at age 18 months. [6]

Prognosis

Most patients are able to live normal lives with the symptoms.

Only patients who receive allergen-specific immunotherapy have resolution of allergic rhinitis (AR) symptoms; however, many patients do very well with intermittent symptomatic care with medication. AR symptoms may recur 2–3 years after discontinuation of allergen immunotherapy, but are usually less severe than the original presentation.

A small percentage of patients improve during the teenage years, but in most, symptoms recur in the early twenties or later. Symptoms begin to wane when patients reach the fifth decade of life.

Patient Education

An abundance of educational material is available from many resources such as medical associations, professional societies (eg, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology), and pharmaceutical companies. All basically instruct the patient to avoid triggers, use medications, and see a specialist if symptoms persist. Some educational materials are very sophisticated, and several pharmaceutical companies provide extensive web sites to assist patients.

For patient education resources, see the Allergy Center, as well as Hay Fever, Indoor Allergies, and Allergy Shots.

-

Photo demonstrates the allergic salute, which is the action performed when a patient rubs the nose using a motion across the nose.

-

Photo demonstrates allergic shiners. Note the periorbital edema and bluish discoloration seen in allergic rhinitis and sinusitis.

-

Impact of nasal allergies.

-

How patient feel when they have allergy symptoms.

-

Nasal symptoms and affect on work performance.