Background

Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSDs) refer to a broad spectrum of malformations characterized by a deficiency of the atrioventricular septum and abnormalities of the atrioventricular valves. These malformations are presumed to result from abnormal or inadequate fusion of the superior and inferior endocardial cushions with the mid portion of the atrial septum and the muscular (trabecular) portion of the ventricular septum.

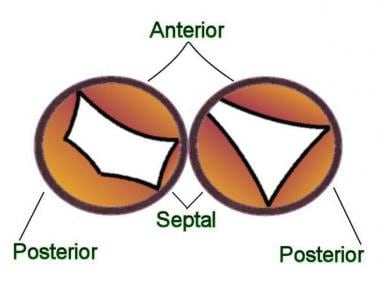

Several methods of classification and nomenclature are recognized, causing considerable confusion. The term partial AVSD (also called partial common atrioventricular canal) generally refers to endocardial cushion defects, which have an interatrial communication but lack an interventricular communication. In these types of defects the mitral and tricuspid annuli are separate. In addition, certain anatomic features should be present, alone or in combination: primum atrial septal defect (ASD), inlet ventricular septal defect (VSD), cleft of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, and wide anteroseptal tricuspid valve commissure or cleft septal tricuspid leaflet (see the image below). The most frequently encountered abnormality in patients with partial AVSD is the combination of primum ASD and cleft of the anterior mitral valve leaflet.

Partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): The mitral and tricuspid annuli are separate. The cleft in the mitral leaflet is in the anterior position. This type of anatomy is usually associated with a primum atrial septal defect (ASD). Partial AVSD is more common than intermediate AVSD.

Partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): The mitral and tricuspid annuli are separate. The cleft in the mitral leaflet is in the anterior position. This type of anatomy is usually associated with a primum atrial septal defect (ASD). Partial AVSD is more common than intermediate AVSD.

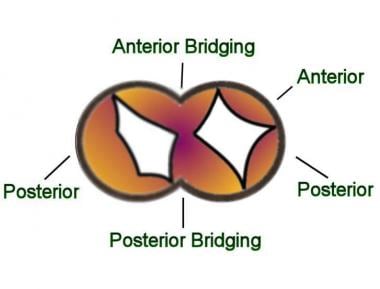

The term intermediate AVSD (also called transitional common atrioventricular canal) is variably defined; however, it most commonly refers to the combination of a partial AVSD with a small interventricular communication. This is an infrequent form of AVSD. A single valvar annulus is usually present where the anterior and posterior bridging leaflets fuse overlying the ventricular septum. Because of the leaflets' fusion, two distinct valvar components are observed (see the image below).

Intermediate atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): A single valve annulus is present. The anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are fused (whereas in complete AVSD the anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are not fused). Therefore, the atrioventricular valve has a tricuspid and a mitral component. Intermediate AVSD is the least common type of AVSD.

Intermediate atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): A single valve annulus is present. The anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are fused (whereas in complete AVSD the anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are not fused). Therefore, the atrioventricular valve has a tricuspid and a mitral component. Intermediate AVSD is the least common type of AVSD.

A thorough description of associated atrioventricular valve abnormalities should be included when classifying these defects.

This article considers AVSDs that demonstrate minimal or no shunting through an interventricular communication.

Pathophysiology

In the absence of obstruction of the right ventricular outflow tract, such as in pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary vascular obstructive disease, predominant left-to-right shunting occurs. The clinical presentation is determined by the degree of interatrial shunting, atrioventricular regurgitation, or both. The most inferior portion of the atrial septum is deficient. The resulting ostium primum defect varies in size and may occur in association with more superior ostium secundum–type ASDs. In some of the latter cases, only a small strand of the atrial septum remains, leading to the appearance of a common atrium. Some observers reserve the term common atrium for those cases with an additional sinus venosus deficiency.

The degree of left-to-right shunting through the atrial defect is determined by the size of the communication and the relative compliance of the 2 atria and ventricles. Ventricular compliance is affected by the level of pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). In the newborn with a less compliant right ventricle (RV) and relatively high PVR, little left-to-right shunting occurs. If the defect is extremely large, obligatory mixing in a common, or near-common, atrium creates a component of right-to-left shunting. Left-to-right shunting increases with age as PVR decreases and RV compliance increases. This results in progressive RV enlargement and pulmonary vascular engorgement.

The atrioventricular valves are abnormal, even in a partial AVSD. Fusion failure of the endocardial cushions usually results in a separation or cleft in the anterior mitral valve leaflet. The degree of regurgitation through the cleft depends on its size and, occasionally, on the presence of left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction or coarctation of the aorta. Typically, the cleft directs regurgitant blood through the atrial defect, creating an LV-to-RA (right atrium) shunt. RA enlargement, rather than left atrial (LA) enlargement, may occur. In addition, mitral regurgitation (MR) contributes to LA and LV enlargement.

Etiology

AVSDs are presumed to occur secondary to extracellular matrix abnormalities that produce faulty development of the endocardial cushions and the atrioventricular septum. It has been recently described that yet another structure, the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, which derives from the second heart field, should also fully develop in order to have an intact 4-chambered heart; otherwise, an ASD or an AVSD occurs. [1]

More detailed scientific theories interpret the normal development of the human heart as an orderly coordination of transcriptional programs. Therefore, the variety and range of anatomic malformations in CHD are believed to be caused by a faulty mechanism that disrupts the above.

AVSDs are often associated with genetic syndromes such as trisomy 21 or Down syndrome; Holt-Oram syndrome, which results from mutations in the TBX5 gene; and heterotaxy syndromes, which result from mutations in genes such as PITX2, SHH, and NODAL. A newly described CRELD1 gene is likely to be an AVSD-susceptibility gene, and CRELD1 mutations may increase the risk of developing a heart defect [2] ; this mutation is believed to be associated with the 3p deletion syndrome [3] characterized by low birth weight, varying degrees of mental retardation, ptosis, and micrognathia. [4]

Genetic mutations may be also associated with nonsyndromic cardiac defects. For example, one of the most important factors for the differentiation of mesodermal progenitor cells is the homeobox protein Nkx-2.5. In humans, 28 germline Nkx-2.5 mutations have been associated with CHD. Studies have shown that mutations in the gene Nkx-2.5 are associated specifically with AVSDs and VSDs. [5] Mutations in the GATA4 transcriptional factor may also cause AVSDs by disrupting its role during different stages in cardiogenesis. [6]

To date, approximately 100 CHD "risk genes" have been described. Of these, six subphenotypes have been shown to be linked to partial AVSDs. Of note, these genes have also been linked to aortic valve stenosis, subaortic stenosis, AVSDs associated with tetralogy of Fallot, tetralogy of Fallot, and truncus arteriosus. [7]

Epidemiology

United States data

Prevalence estimates of cardiovascular malformations in large cohorts vary from 4-8 cases per 1000 births. AVSD constitutes 5-8% of these defects. Incidence of AVSD in fetuses is 17%; however, occurrence of partial AVSD has not been separated from this general classification.

Studies report the incidence of congenital heart defect (CHD) in children with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) to be 42-48%. Of those CHDs, 45% are AVSDs.

In general, when not associated with heterotaxia syndrome, AVSDs commonly occur in Down syndrome.

Partial AVSD, as opposed to complete AVSD, of the ostium primum type is more common in patients without Down syndrome.

International data

International frequency of cardiovascular malformations is similar to US figures.

Prognosis

Mortality/Morbidity

Left-to-right shunting through the atrial communication is generally well tolerated through the first decade of life. Patients are asymptomatic if MR is mild or absent. Symptoms of left-to-right shunting may develop in adolescence and are exacerbated by atrial arrhythmia. Sinus node dysfunction may occur and contributes to exercise intolerance if the defect is not repaired.

Moderate to severe MR may lead to morbidity in infancy and early childhood. Severe MR causes congestive heart failure (CHF) and failure to thrive in infants; it may result in death if left untreated.

A large left-to-right shunt from the LV to the RA through a cleft mitral valve causes volume overload in both ventricles, with CHF early in life.

Miller et al reviewed the long-term survival of infants with all types of atrioventricular septal defects with Down syndrome (n = 177) and without Down syndrome (n = 161). In this cohort, born from 1979-2003, overall survival probability through 2004 was 70% in those with Down syndrome and 69% in those without. Mortality was higher in children with a complex atrioventricular septal defect and in those with 2 or more major noncardiac malformations, but was lower in children born in 1992-2003. [8]

-

Partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): The mitral and tricuspid annuli are separate. The cleft in the mitral leaflet is in the anterior position. This type of anatomy is usually associated with a primum atrial septal defect (ASD). Partial AVSD is more common than intermediate AVSD.

-

Intermediate atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD): A single valve annulus is present. The anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are fused (whereas in complete AVSD the anterior and posterior bridging leaflets are not fused). Therefore, the atrioventricular valve has a tricuspid and a mitral component. Intermediate AVSD is the least common type of AVSD.

-

Echocardiogram of the apical 4-chamber view demonstrating a partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). Chambers are denoted by RA (right atrium), RV (right ventricle), and LV (left ventricle).

-

Echocardiogram with subcostal view demonstrates an atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD). A portion of the ostium secundum atrial septum is also missing, just superior to the ostium primum defect.

-

Color Doppler demonstrates left-to-right shunting through the partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) shown in the following images.

-

Left superior axis deviation in the frontal plane and rR' pattern in right precordial leads.