Practice Essentials

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common pediatric infections. It distresses the child, concerns the parents, and may cause permanent kidney damage. Occurrences of a first-time symptomatic UTI are highest in boys and girls during the first year of life and markedly decrease after that.

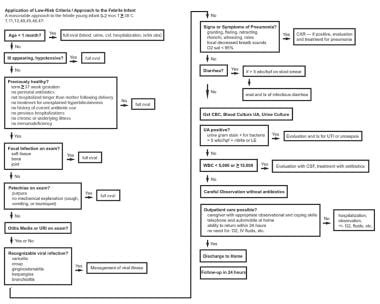

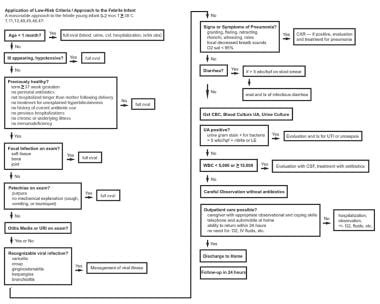

Febrile infants younger than 2 months constitute an important subset of children who may present with fever without a localizing source. The workup of fever in these infants should always include evaluation for UTI. The chart below details a treatment approach for febrile infants younger than 3 months who have a temperature higher than 38°C.

Application of low-risk criteria for and approach to the febrile infant: A reasonable approach for treating febrile infants younger than 2 months who have a temperature of greater than 38°C.

Application of low-risk criteria for and approach to the febrile infant: A reasonable approach for treating febrile infants younger than 2 months who have a temperature of greater than 38°C.

Signs and symptoms

The history and clinical course of a UTI vary with the patient's age and the specific diagnosis. No one specific sign or symptom can be used to identify UTI in infants and children.

Children aged 0-2 months

Neonates and infants up to age 2 months who have pyelonephritis usually do not have symptoms localized to the urinary tract. UTI is discovered as part of an evaluation for neonatal sepsis. Neonates with UTI may display the following symptoms:

-

Jaundice

-

Fever

-

Poor feeding

-

Vomiting

-

Irritability

Infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years

Infants with UTI may display the following symptoms:

-

Poor feeding

-

Fever

-

Vomiting

-

Strong-smelling urine

-

Abdominal pain

-

Irritability

Children aged 2-6 years

Preschoolers with UTI can display the following symptoms:

-

Vomiting

-

Abdominal pain

-

Fever

-

Strong-smelling urine

-

Enuresis

-

Urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency)

Children older than 6 years and adolescents

School-aged children with UTI can display the following symptoms:

-

Fever

-

Vomiting, abdominal pain

-

Flank/back pain

-

Strong-smelling urine

-

Urinary symptoms (dysuria, urgency, frequency)

-

Enuresis

-

Incontinence

Physical examination findings in pediatric patients with UTI can be summarized as follows:

-

Costovertebral angle tenderness

-

Abdominal tenderness to palpation

-

Suprapubic tenderness to palpation

-

Palpable bladder

-

Dribbling, poor stream, or straining to void

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) criteria for the diagnosis of UTI in children 2-24 months are the presence of pyuria and/or bacteriuria on urinalysis and of at least 50,000 colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of a uropathogen from the quantitative culture of a properly collected urine specimen. [1]

Urinalysis alone is not sufficient for diagnosing UTI. However, urinalysis can help in identifying febrile children who should receive antibacterial treatment while culture results from a properly collected urine specimen are pending. [2]

Urine specimen collection

-

A midstream, clean-catch specimen may be obtained from children who have urinary control

-

Suprapubic aspiration or urethral catheterization should be used in the infant or child unable to void on request

Suprapubic aspiration is the method of choice for obtaining urine from the following patients:

-

Uncircumcised boys with a redundant or tight foreskin

-

Girls with tight labial adhesions,

-

Children of either sex with clinically significant periurethral irritation

Culture of a urine specimen from a sterile bag attached to the perineal area has a false-positive rate too high to be suitable for diagnosing UTI; however, a negative culture is strong evidence that UTI is absent. [1]

Laboratory studies

-

Complete blood count (CBC) and basic metabolic panel (for children with a presumptive diagnosis of pyelonephritis)

-

Blood cultures (in patients with suspected bacteremia or urosepsis)

-

Renal function studies (ie, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen [BUN] levels)

-

Electrolyte levels

Imaging studies

Imaging studies are not indicated for infants and children with a first episode of cystitis or for those with a first febrile UTI who meet the following criteria:

-

Assured follow-up

-

Prompt response to treatment (afebrile within 72 h)

-

A normal voiding pattern (no dribbling)

-

No abdominal mass

If imaging studies of the urinary tract are warranted, they should not be obtained until the diagnosis of UTI is confirmed. Indications for renal and bladder ultrasonography are as follows:

-

Febrile UTI in infants aged 2-24 months [1]

-

Delayed or unsatisfactory response to treatment of a first febrile UTI

-

An abdominal mass or abnormal voiding (dribbling of urine)

-

Recurrence of febrile UTI after a satisfactory response to treatment

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) may be indicated after a first febrile UTI if renal and bladder ultrasonography reveal hydronephrosis, scarring, obstructive uropathy, or masses or if complex medical conditions are associated with the UTI. VCUG is recommended after a second episode of febrile UTI. [1]

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Patients with a nontoxic appearance may be treated with oral fluids and antibiotics. Outpatient care is reasonable if the following criteria are met:

-

A caregiver with appropriate observational and coping skills

-

Telephone and automobile at home

-

The ability to return to the hospital within 24 hours

-

The patient has no need for oxygen therapy, intravenous fluids, or other inpatient measures

Hospitalization is necessary for the following patients with UTI:

-

Patients who are toxemic or septic

-

Patients with signs of urinary obstruction or significant underlying disease

-

Patients who are unable to tolerate adequate oral fluids or medications

-

Infants younger than 2 months with febrile UTI (presumed pyelonephritis)

-

All infants younger than 1 month with suspected UTI, even if not febrile

Treat febrile UTI as pyelonephritis, and consider parenteral antibiotics and hospital admission for these patients.

Antibiotics for parenteral treatment are as follows:

-

Ceftriaxone

-

Cefotaxime

-

Ampicillin

-

Gentamicin

Patients aged 2 months to 2 years with a first febrile UTI

If clinical findings indicate that immediate antibiotic therapy is indicated, a urine specimen for urinalysis and culture should be obtained before treatment is started. Common choices for empiric oral treatment are as follows:

-

A second- or third-generation cephalosporin

-

Amoxicillin/clavulanate, or sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP)

Children with cystitis

-

Antibiotic therapy is started on the basis of clinical history and urinalysis results before the diagnosis is documented

-

A 4-day course of an oral antibiotic agent is recommended for the treatment of cystitis

-

Nitrofurantoin can be given for 7 days or for 3 days after obtaining sterile urine

-

If the clinical response is not satisfactory after 2-3 days, alter therapy on the basis of antibiotic susceptibility

-

Symptomatic relief for dysuria consists of increasing fluid intake (to enhance urine dilution and output), acetaminophen, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

-

If voiding symptoms are severe and persistent, add phenazopyridine hydrochloride (Pyridium) for a maximum of 48 hours

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common pediatric infections. It distresses the child, concerns the parents, and may cause permanent kidney damage. Prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of a febrile UTI may prevent acute discomfort and, in patients with recurrent infections, kidney damage. (See Presentation, DDx, Treatment, and Medication.)

The 2 broad clinical categories of UTI are pyelonephritis (upper UTI) and cystitis (lower UTI). The most common causative organisms are bowel flora, typically gram-negative rods. Escherichia coli is the organism that is most commonly isolated from pediatric patients with UTIs. However, other organisms that gain access to the urinary tract may cause infection, including fungi (Candida species) and viruses. (See Pathophysiology and Etiology.)

The febrile infant or child who has no other site of infection to explain the fever, even in the absence of systemic symptoms, should be assessed for the likelihood of pyelonephritis (upper UTI). Most episodes of UTI during the first year of life are pyelonephritis. (See DDx.)

Febrile infants younger than 2 months constitute an important subset of children who may present with fever without a localizing source. The workup of fever in these infants should always include evaluation for UTI. The chart below details a treatment approach for febrile infants younger than 3 months who have a temperature higher than 38°C. (See Presentation and DDx.)

Application of low-risk criteria for and approach to the febrile infant: A reasonable approach for treating febrile infants younger than 2 months who have a temperature of greater than 38°C.

Application of low-risk criteria for and approach to the febrile infant: A reasonable approach for treating febrile infants younger than 2 months who have a temperature of greater than 38°C.

Children with UTIs who have voiding symptoms or dysuria, little or no fever, and no systemic symptoms, likely have cystitis. After age 2 years, UTI in the form of cystitis is common among girls.

In rare instances, UTI results in recognition of an important underlying structural or neurogenic abnormality of the urinary tract. [2] Some clinically significant urinary tract abnormalities may be identified using intrauterine ultrasonography. After birth, children with such abnormalities may incur additional kidney damage as a result of postnatal infection, but UTI is not the major cause of the kidney impairment.

Go to Urinary Tract Infection in Males and Cystitis in Females for complete information on these topics. For patient education information, see Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and Bladder Control Problems.

Pathophysiology

Typically, UTIs develop when uropathogens that have colonized the periurethral area ascend to the bladder via the urethra. From the bladder, pathogens can spread up the urinary tract to the kidneys (pyelonephritis) and possibly to the bloodstream (bacteremia). Poor containment of infection, including bacteremia, is more often seen in infants younger than 2 months.

Urine in the proximal urethra and urinary bladder is normally sterile. Entry of bacteria into the urinary bladder can result from turbulent flow during normal voiding, voiding dysfunction, or catheterization. In addition, sexual intercourse or genital manipulation may foster the entry of bacteria into the urinary bladder. More rarely, the urinary tract may be colonized during systemic bacteremia (sepsis); this usually happens in infancy. Pathogens can also infect the urinary tract through direct spread via the fecal-perineal-urethral route.

Etiology

Bacterial infections are the most common cause of UTI, with E coli being the most frequent pathogen, causing 75-90% of UTIs. Other bacterial sources of UTI include the following:

-

Klebsiella species

-

Proteus species

-

Enterococcus species

-

Staphylococcus saprophyticus, especially among female adolescents and sexually active females

-

Streptococcus group B, especially among neonates

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Fungi (Candida species) may also cause UTIs, especially after instrumentation of the urinary tract. Adenovirus is a rare cause of UTI and may cause hemorrhagic cystitis.

Genetic factors

Deregulation of candidate genes may predispose patients to recurrent UTIs. The identification of a genetic component may allow the identification of at-risk individuals and, therefore, prediction of the risk of recurrent UTI in their offspring. [3] Genes that are possibly responsible for susceptibility to recurrent UTIs include HSPA1B, CXCR1, CXCR2, TLR2, TLR4, and TGFβ1. [3]

Risk factors

Susceptibility to UTI may be increased by any of the following factors:

-

Alteration of the periurethral flora by antibiotic therapy

-

Anatomic anomaly

-

Bowel and bladder dysfunction

-

Constipation

Children who receive antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin, cephalexin) for other infections are at increased risk for UTI. These agents may alter gastrointestinal (GI) and periurethral flora, disturbing the urinary tract's natural defense against colonization by pathogenic bacteria.

Prolonged retention of urine may permit incubation of bacteria in the bladder. Voiding dysfunction is not usually encountered in a child without neurogenic or anatomic abnormality of the bladder until the child is in the process of achieving daytime urinary control.

A child with uninhibited detrusor contractions may attempt to prevent incontinence during a detrusor contraction by increasing outlet resistance. This may be achieved by using various posturing maneuvers, such as tightening of the pelvic-floor muscles, applying direct pressure to the urethra with the hands, or performing the Vincent curtsy, which consists squatting on the floor and pressing the heel of one foot against the urethra. As a result, bacteria-laden urine in the distal urethra may be milked back into the urinary bladder (urethrovesical reflux).

Constipation, with the rectum chronically dilated by feces, is an important cause of voiding dysfunction. Neurogenic or anatomic abnormalities of the urinary bladder may also cause voiding dysfunction.

Voiding dysfunction should be evaluated and managed appropriately. Surgical correction of underlying anatomic disorders may be indicated in select cases. For more information, see Pediatric Vesicoureteral Reflux.

Circumcision and UTI

For male infants, neonatal circumcision substantially decreases the risk of UTI. Schoen et al found that during the first year of life, the rate of UTI was 2.15% in uncircumcised boys, versus 0.22% in circumcised boys. [4] Risk is particularly high during the first 3 months of life; Schaikh et al reported that in febrile boys younger than 3 months, UTI was present in 2.4% of circumcised boys and in 20.1% of uncircumcised boys. [5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of UTIs varies based on age, sex, and gender. Overall, UTIs are estimated to affect 2.4-2.8% of children in the United States annually.

Occurrences of first-time, symptomatic UTIs are highest in boys and girls during the first year of life and markedly decrease after that. Shaikh et al found that the overall prevalence of UTI in infants presenting with fever was 7.0%. [4] By age, the rates in girls were as follows:

-

0-3 months - 7.5%

-

3-6 months - 5.7%

-

6-12 months - 8.3%

-

>12 months - 2.1%

In febrile boys less than 3 months of age, 2.4% of circumcised boys and 20.1% of uncircumcised boys had a UTI. [4]

Sex- and race-related demographics

During the first few months of life, the incidence of UTI in boys exceeds that in girls. By the end of the first year and thereafter, first-time and recurrent UTIs are most common in girls. The incidence of UTI in children aged 1-2 years is 8.1% in girls and 1.9% in boys.

Studies from Sweden have indicated that at least 3% of girls and 1% of boys have a symptomatic UTI by age 11 years. Other data, however, have suggested that 8% of girls have a symptomatic UTI during childhood and that the incidence of a first-time UTI in boys older than 2 years is probably less than 0.5%. In sexually active teenage girls, the incidence of UTIs approaches 10%.

In studies by Hoberman et al, the prevalence of febrile UTIs in white infants exceeded that in black infants. [6] These investigators found that among white female infants younger than 1 year who had a temperature of 39°C or more and were seen in an emergency department, 17% had UTI.

Prognosis

Mortality related to UTI is exceedingly rare in otherwise healthy children in developed countries.

Cystitis may cause voiding symptoms and require antibiotics, but it is not associated with long-term, deleterious kidney damage. The voiding symptoms are usually transient, clearing within 24-48 hours of effective treatment.

Morbidity associated with pyelonephritis is characterized by systemic symptoms, such as fever, abdominal pain, vomiting, and dehydration. Bacteremia and clinical sepsis may occur. [7]

Children with pyelonephritis may develop focal inflammation of the kidney (focal pyelonephritis) or renal abscess. Any inflammation of the renal parenchyma may lead to scar formation. Approximately 10-30% of children with UTI develop some renal scarring; however, the degree of scarring required for the development of long-term sequelae is unknown.

Long-term complications of pyelonephritis are hypertension, impaired renal function, and end-stage renal disease.

Dehydration is the most common acute complication of UTI in the pediatric population. Intravenous fluid replacement is necessary in more severe cases.

In developed countries, kidney damage with long-term complications as a consequence of UTI has become less common than it was in the early 20th century, when pyelonephritis was a frequent cause of hypertension and end-stage renal disease in young women. This change is probably a result of improved overall healthcare and close follow-up of children after an episode of pyelonephritis. Currently, these complications are most commonly encountered in infants with congenital renal damage. [8, 9]

-

Application of low-risk criteria for and approach to the febrile infant: A reasonable approach for treating febrile infants younger than 2 months who have a temperature of greater than 38°C.